So much has been made in recent weeks, and will continue to be made throughout the year, of the two hundredth anniversary of the birth of George Washington, that it may be well to include in this place a momentary recognition of a noteworthy festival. The thing that thus far appears to impress most commentators is the fact that in the case of Washington—and in that of Lincoln as well, who was also a February childthe important thing was not formal education—neither man had enough of it to count—but character. Indeed James Truslow Adams in his admirable "Epic of America" rates the character of Washington as the most important asset of the rebellious colonies for the attainment of success in the Revolution. It was vitally important that at the moment England was engaged in war with half Europe; but even so, failing the character of Washington, it is improbable that the cause of the colonies in America could have been made good.

Character has been referred to by educators, we believe, as a "by-product," but that may do it a serious injustice. Engaged as the colleges and schools are in seeking to spread intelligence as widely as possible among the American public, such character as results is bound to be more or less an incidental; but the importance of the by-products in every line of work has come to be more generally appreciated now than it was once. The stress in any institution devoted to formal learning is bound to be on that, chiefly, but surely the development of character cannot be ignored. The thing itself is more or less innate, and the development of it, rather than the creation of it, may be what the colleges need to have most in view.

Washington never went to any college. His elder brother had been educated with some elaborateness in England, whereas George, because of straitened circumstances at home, was forced to content himself with the rudimentary training of small country schools and the larger instructions of hard experience. Yet it is George whom the world remembers, and not Lawrence. Lincoln had barely a year's actual schooling in his whole life. What the effect of more extensive schooling would have been on either is a matter of conjecture, and rather profitless conjecture at that. It is not to be cited as proving that an absence of formal education is certainly to be preferred, in the rash assumption that it would produce more Lincolns and more Washingtons. It may, however, lend point to the assertion that there is something beyond book-learning, which it is incumbent on schools and colleges to recognize and cultivate—and it may even have a bearing on that oft-mooted point that athletics interfere with the time which otherwise could be devoted to a closer study of literature, mathematics and the sciences.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1932 By Frederick William andres -

Article

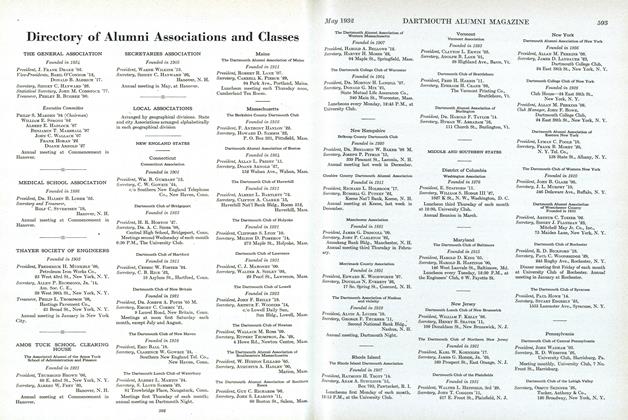

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

May 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

May 1932 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

ArticleA Student in the Early Eighteen Hundreds

May 1932 By Mary B. Slade -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

May 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

ArticleLetch worth Village—A Home for Mental Defectives

May 1932 By Charles S. Little, M.D.

Article

-

Article

ArticleScholarships Announced

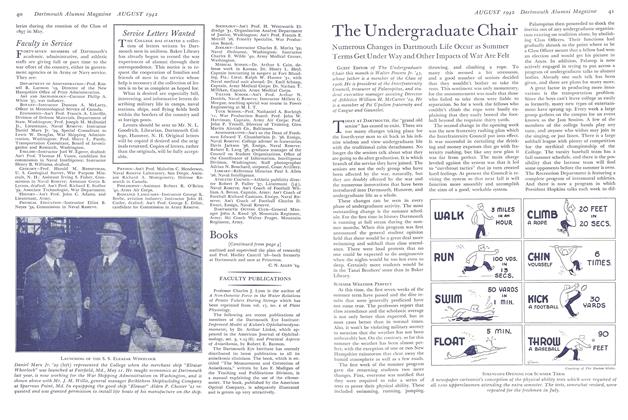

August 1942 -

Article

Article1957

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Bruce Sloane -

Article

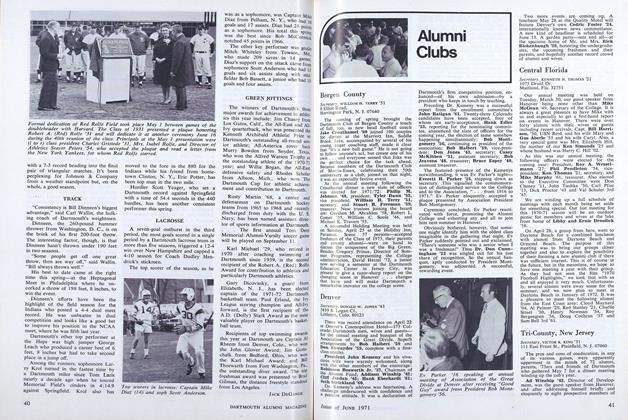

ArticleTRACK

JUNE 1971 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleIF YOU WANT TO PLAY, YOU'VE GOT TO PAY

May/June 2008 By Lauren Smith '08 -

Article

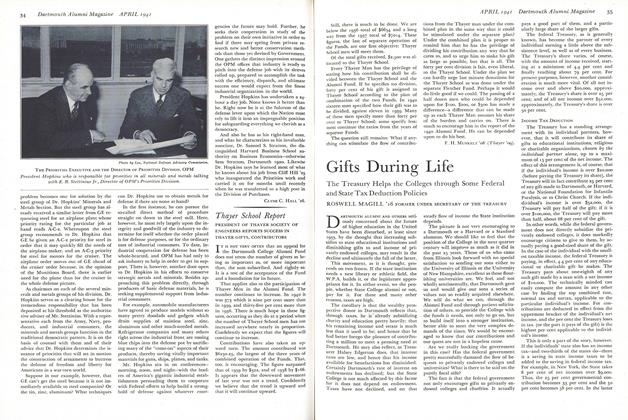

ArticleGifts During Life

April 1941 By ROSWELL MAGILL '16 -

Article

ArticleThe Robot at the Gate

NovembeR | decembeR By Theresa D’Orsi