By Leonard D. White '14, New York, McGraw-Hill Company, 1933.

Do the American people stand at the threshold of a new era in governmental adaptation to our world of economic change? Norman Thomas in his recent Dartmouth lecture pointed out that our governmental thinking is archaic compared to our economic progress. Leonard D. White in this volume, one of a series of monographs published under the direction of the President's Research Committee on Social Trends, presents a view of the most progressive area in the whole field of American government—public administration. Anyone reading the 341 pages of this survey of public administrative trends in the last thirty-two years will be inclined to add reservations to Mr. Thomas' statement. This careful study certainly does leave one with the feeling that here we have a phase of government adapting itself more nearly to economic change.

In part one, the author vividly describes the retreat of the theory of the separation of powers before public administration. The administration of our laws is gravitating from state to the nation and from the municipality and the county to the state. Likewise there is centralization within each unit of government to the detriment of separation of powers. And where outworn constitutions, statutes and court decisions intervene, administrative officials are attaining unity by streching their powers, by supervisory powers, and in leadership dependent on voluntary cooperation. In the public mind efficiency and centralization go hand in hand. This is noticeably true as regards the administrative status of transportation, finance, education, public health and other public welfare activities. Only in municipal home rule movements is there any tendency toward a strengthening of smaller as against the larger and higher units of government. And even here one must question whether home rule is not largely illusory.

The rural Jacksonian philosophy of spoils, rotation in office, and disintegrated control is slowly giving way before the new management. This implies the rise of the permanent expert, the integrated administrative machine, and the office (such as the Federal Budget Bureau) set for executive control of administration. In 1900 the typical American executive was principally a political official acting upon a legislative body in order to bring some semblance of unity in an organization made up of many independent units, save for common financial dependence on the legislature. Today administrative machines are being integrated under the President, the governor and the mayor—not always with the happie st results under poor chief executives. In order to avoid the danger of the politically controlled executive over four hundred cities are experimenting with the city manager, who represents the administrative expert in complete charge of a highly integrated administration. He is no longer, in theory at least, a political leader but rather an unhampered leader of administration. In summarizing this part of his survey Professor White writes: "Viewed in the large, the new management has much significance. It reflects the rapid decline of a long era of suspicion of the executive power which for a century has hampered the growth of adequate administrative organization. It represents a new impress of the pattern of business ideals and methods on government, with an unascertained mixture of gains and losses. It foreshadows at least a definite modification of the American theory of democracy. . . . It marks the lessening of the direct influence of the 'common man' in administrative office and the strengthening of the role of the expert. . . . To the extent that the new management commands public confidence, it promotes the further expansion of public activities."

The rise of the expert has focused a great deal of attention on trends in public employment. The rapid increase in professional, technical and scientific employees in public administration seems destined to continue. This and the general growth in number of civil servants presents questions of recruitment, promotion, training, retirement, incentives, democratic representation of employees, and relationship to the public. Only a start has been made on these problems. To aid in the solution of these and other problems of administration dealt with in the previous parts of the survey, there has been a significant development of research organizations, usually privately financed. These organizations have as their purpose the improvement in the technique of public administration.

Professor White concludes that the trends in American administration are conservative when compared with those in Russia, Italy and England, but in the author's words: "Whatever may be the experience of the next decade ... it remains a matter of record that the last decade has produced a greater change in the organization of American government than probably any similar period in our history." The trends in American public administration "should spell greater public confidence in government as one agency of social amelioration, and should make more certain the gradual displacement of the police state by the service state."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

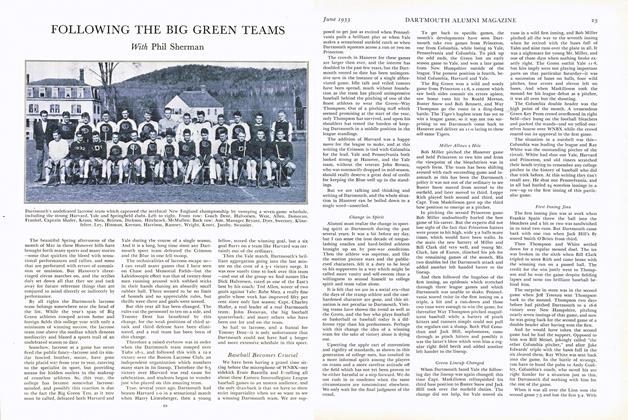

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1933 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

June 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticlePIONEERING IN TELEGRAPHY

June 1933 By William U. Swan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of IQ9 1

June 1933 By Jack R. Warwick -

Article

ArticleSecretaries Convene

June 1933

Milton V. Smith

Books

-

Books

BooksDartmouth Authors

APRIL • 1985 -

Books

BooksShelf Life

Sep - Oct -

Books

BooksARGENTINA, BRAZIL AND CHILE SINCE INDEPENDENCE

April 1937 By J. M. Arce -

Books

BooksINTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL PROCEDURE

November, 1930 By W. A. Robinson -

Books

BooksATLAS OF GENERAL SURGERY.

January 1957 By WILLIAM T. MOSENTHAL '38, M.D. -

Books

BooksGOLDEN MOMENTS IN AMERICAN SCULPTURE.

OCTOBER 1967 By WINSLOW EAVES