A Review of the 1948 Season, Described Here As Maybe the Finest in the Green Record Book

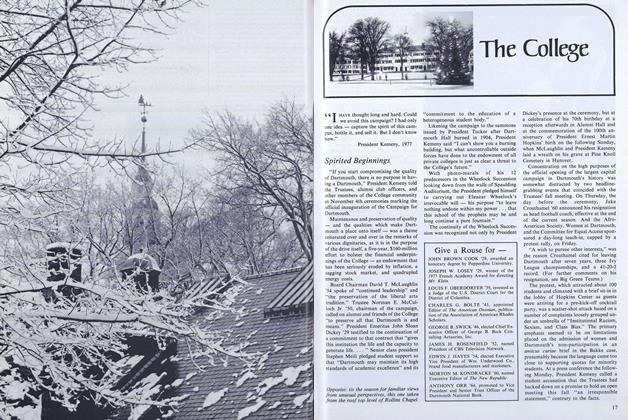

A MUSICAL footnote in The Dartmouth, published, if memory serves, for the benefit of the undergraduates and their ladies assembled for the house parties built around the Columbia game, said it possibly as neatly as it could be said. The date of the game was November 6. This was the big Memorial Field attraction of the year, the fall house-party weekend, and the sixth contest in Dartmouth's eight-game, all-major-game schedule.

Captain Dale Armstrong's husky, freewheeling eleven had lost the opener to Pennsylvania, but then had taken in succession Holy Cross, Colgate, Harvard and Yale. "Taken" is scarcely the word to apply to their just-completed mission versus the scions of Eli. They had blasted the Blue, 41-14, and many of the metropolitan scribes who had witnessed the operation had been replaying the Dartmouth part of it in their columns all week.

Now came. Columbia, and the youth and beauty of the big autumnal party, and the college daily, hospitably greeting and explaining to all, printed, along with the rest, the words of the Touchdown Song. I'm writing from Boston, and from memory, so far as this is concerned, being unable to check The Dartmouth's files, but the gist of that bit of musical marginalia was approximately as follows:

It said that it was printing the words of the Touchdown Song in order that the students could learn them. This was one of the old football songs that was undergoing a revival it explained. Evidently Once popular with Dartmouth cheering sections, mass meetings at al, it had gone into such a decline that few of the current generation knew it. Now it seemed to be coming back, but not very successfully with anything but the Band. Here it was, if anybody wanted to learn it, more or less, said The Dartmouth, and then it added it didn't know why the ancient madrigal had slipped into desuetude, unless it was because Dartmouth hadn't been making very many touchdowns through the period of its decline.

That said it. Dartmouth hadn't been making very many touchdowns for a number of years. The old Indian was a weak, undernourished, fairly pathetic looking specimen. Don't ask me why. I'm not privy to the inner workings and problems. The war and the preparations for war undoubtedly had much to do with it. Mixed up with other matters, as most of us were, I wasn't even in Hanover, nor did I see a football game during the war. Run of material, such as was available, probably played its part. I heard the usual complaints that the Admissions Office frowned on any applicant more than five feet high, and with a neck size bigger than 13 1/2, but that was hearsay, third and fourth removed.

I don't know what shrunk the once hearty aborigine to the appearance of something freshly liberated from Buchenwald, and all that makes no difference now, because with the end of the war, the football division of our revered institution began to be repopulated with a delegation of young gentlemen who ran to size, and who likewise could run, kick, and pass the football. And lest this loving thesis fall into alien hands, and the preceding sentence, long as it is, be deliberately misinterpreted, I hasten to add that they were, and are, strictly students and gentlemen, not mercenaries, and pledges to the National Professional Football League.

The happier times started last year, meaning 1947, when Tuss McLaughry and his adjutants began to preside over a working squad that included 22 sophomores. They were, naturally, as green as the jerkins they wore, their schedule was all-major, and they didn't figure to win many ball games. What they did figure to do, was to develop under careful coaching, and expert shaping into a fire-hardened, battle-wise, self-confident brigade- that, given the breaks, and a few especial talents, would be a fine team another yearthat would be in 1948—and, if all went as it could, and generally does, a great team their senior season—that would be the next 0ne—1949.

The 1948 part of it proceeded to come true. As a man grows older, he learns to be sparing with his superlatives, but this was, at least, a fine Dartmouth team. At the end of the season, playing the game I saw it play against Princeton, I'm none too certain it wasn't the best team in the East, and I saw Army, generally accorded that rating, play twice—both times against climax opposition, Pennsylvania and Navy. Arguments such as that, of course, can never be settled, but we can stick to facts, and the 1948 Indians manufactured some record-breaking facts.

The following are. officially to their credit:

(1) They were the first team in Dartmouth history to win six major games in one season. (The 1920—Hear! Hear!1936 and 1943 units won five). (2) They were the first Dartmouth team to win five consecutive major victories. (The rest of us had ties, losses, or runaways over pushovers sandwiched into our historic performances). (3) They scored 13 touchdowns with forward passes for the alltime Green record. (The 1925 teamOberlander to Tully and Sage—held the mark up to then with a dozen.)

(4) They ran up the highest point total ever scored by Dartmouth against Yale {4l-14), and ditto versus Colgate (41-16). {5) They scored more, points against major opposition than ally team in Dartmouth history (213).

Getting into individual performances, Johnny Clayton, the sensational sophomore quarterback (height, 6:00, weight, 191 pounds), completed 46 of 90 passes for a new Dartmouth record. Clayton likewise hit the target 10 times on touchdown passes. Swede Oberlander, now the distinguished Dr. Andrew James Oberlander, still tops him there. The eminent Medical Director of the Vermont National Life Insurance Company, whose battle cry in his gridiron years was, so it read in The Boston Post anyhow, "Ten Thousand Swedes Jumped Out of the Weeds at the Battle of Copenhagen," threw 14 scoring passes in 1925. Tom (Red) Rowe, Dartmouth's 6:03 end, was not only one of the national leaders in snaring touchdown passes, but he also tied George Tully's 1925 mark by completing and scoring with seven. Myles Lane, also of the 1925 team, holds the all-time Dartmouth record with eight, but Myles, as all that day and generation remembers, was a halfback.

Statistics such as these could go on to greater space than I have currently at command. Dartmouth's total offense rec- ord of 345.5 yards gained per game was second only to Army in the East, and 14th among the major colleges of the nation. Although, due to losses to Pennsylvania and Cornell, Dartmouth finished third in the Ivy League standing behind Cornell and Penn, Dartmouth won as many Ivy games (four) as either, and scored more points than any other team in this entire unofficial group (153). The 1948 Dartmouth team was the second in Green history to defeat Harvard, Yale and Prince, ton in the same season. Dartmouth's tgjg unit did it first, and is the only other one that ever did, but 1948 outscored lgjj against these three, racking up 88 points against the ancient trio for another alltime Dartmouth record.

This could go on, but I can't-and come to what I'm trying to say. First, there will undoubtedly be many amongst the elders who'll wonder why all this exuberance about a team that was beaten. They'll want to know, if it was all this good, why was it beaten?

Dartmouth was beaten, 26-13, by Pennsylvania in the opening game of the season. No alibis are offered, nor are any in order. Penn, at that time, was considered the powerhouse of the East. She cracked under pressure later when a hard schedule proved that with the graduation of Minisi and other backs, she lacked, in ultimate analysis, the -attack to match her mightv Chuck Bednarik-led line. Nobody knew that, however, when the Green charged her at Philadelphia.

These were the Dartmouth sophomores, playing their first game as juniors. Clay- ton was a sophomore playing his first varsity game. Maybe there was some subconscious stage fright. Maybe this Dartmouth team hadn't yet learned what it packed in its quiver. Maybe Pennsylvania was the better team and would, have beaten it at any time. Writers who saw it —I was at the World Series—said; "Dartmouth lost through a couple of sophomorish mistakes." I didn't believe it at the time, but I could believe it later after having seen both teams in later action.

Dartmouth's other loss was By one point, 27-26, to Cornell. The Big Green seemed to be better than the hard-fighting Big Red, and led nicely into the final quarter at Ithaca. Then Cornell proceeded to stage a hell-roaring finish, in singularly wicked weather, and clearly earned a thrilling victory. Dartmouth had had to fight desperately to stave off a similar lastminute uprising by Columbia the previous week. It began to look a little as if the Green could win 'em but couldn't hold 'em.

That wasn't entirely true. Nobody wants to discount the victories of splendid and valiant opponents. They won. The scores stand. We duly salute them. Maybe we never could have licked them. That's freely and fully granted. There's no law, sporting or otherwise, that forbids our analysis of our own strengths and weakness here in the bosom of the lodge, however, and our weakness was lack of reserve strength in the line, especially at the tackles. Maybe we never could have held the suddenly raging Red at Ithaca, but, hold them or not, the sudden trouble on our side was that we ran out of tackles.

Old timers have got to realize that this is now an entirely different kind of football. The unlimited substitution business has changed the game. It's now a high speed contest of continually fresh and rested players. The tempo is terrific. Earl Blaik, recently talking with writers said, "The game is now so fast, I doubt that any player could keep up with the others for 6o full minutes. Our teams (meaning Army) are so much faster than my teams were at Dartmouth, that the two wouldn't belong in the same game." If you remember, we thought Mr. Blaik's Dartmouth teams were very fast, and, for one, I still think they were.

One of the brightest stars in the 1948 Dartmouth crown was gilded from that changed situation. The Dartmouth staff used unlimited substitution, to be sure, but it lacked the squad size to substitute full elevens. It was really short of line material to take full advantage of this new style of play, and the fact that the team did what it did without a full stock of manpower is a powerful extra plus to its credit.

The game has changed in another way, too, and now we're back to those, if any there be, who ask, "Why all this hurrah about a team that was beaten?" The traditional way was, and still is, to hail an unbeaten team, automatically as a championship unit, a Bowl game nominee and a candidate for immortality.

Those days are rapidly on the way out, if they aren't already gone, in major circles. The catalytic agent here is the all-major-game schedule, of the type Dartmouth has played since Tuss McLaughry returned from the Marine Corps in 1945, the type she'll play next season, and the type all the Ivy League Colleges, and most other majors, are adopting. Unless this swings back, an unlikely possibility, there'll be very few "undefeated and untied" elevens henceforth in the circles in which we move. There was none in all the East, nor, in fact, on the entire Atlantic Seaboard north of North Carolina this past season.

The Dartmouth schedule of 1948 reads: Pennsylvania, Holy Cross, Colgate. Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Cornell and Princeton.

Let's take a fast glance at the schedules of some of the storied and glorified Dartmouth units of yore, teams whose feats and individuals rest in our tribal immortality. This isn't belittlin', please understand, nor am I trying to maintain that these cited were the best. I cite them merely in the belief that they were typical and because they'll be easily recallable to a great many memories.

Going way back to the power house of 1903, the one with the immortal Heinie Hooper, Myron Witham and the other paladins who dedicated the Harvard Stadium with a 11-0 victory: It won nine games, it scored 232 points to 23 scored against it by its combined opposition. But its schedule was: Mass. Aggie, Holy Cross, Vermont, Union, Williams, Princeton, Weslevan. Amherst. Harvard and Brown. It lost to Princeton, 17-0.

The 1911 team, famed for "the bounding Princeton dropkick." but likewise historical for all-time personnel, went undefeated through: Norwich, Mass. Aggie (now the University of Massachusetts, incidentally), Bowdoin, Colby, Holy Cross, Williams, Vermont and Amherst. Then it lost, 3-0, to Princeton and 5-3 to Harvard.

We surviving veterans of the 1919, postWorld War 1, ex-G.I. unit like to visualize ourselves as the toughest that ever scarred sod, or the physiognomies of the opposition. with cleats. Waiving all claims to modesty, we were pretty good. That was the Jack Cannell-Jim Robertson-Swede Youngstrom-Gus Sonnenberg-Cuddv Murphy-Guy Cogswell etc. unit. We went the distance to an anticlimatic game with Brown in Boston, which we lost by one point, after having suffered heavy casualties' in that famous 20-19 Donnybrook with Penn the previous Saturday in New York.

Our schedule, especially the latter part of it, was tough because all major college elevens that first post-war season were tough, but scan the first part of it. It ran: Springfield, Norwich, Mass. Aggie, Penn State, Cornell. Colgate, Pennsylvania and Brown.

The great, high-scoring, undefeated, and not-even-close-to-tied Jess Hawley coached team of 1925, whose records have mostly stood until now, may possibly have been the greatest the College ever knew. It defeated Harvard. 32-9; Cornell, 62-13; and Chicago, 33-7. Possibly it could have prevailed as easily against a full list of that class. Its other opponents, however, were: Norwich, which it defeated, 59-0; Hobart, which it took mercy on, 34-0; Vermont, which it chased home, 50-0; Maine, which it shagged, 56-0, and Brown, which it eased up on, 14-0.

Even the best of the Earl Blaik teams, the two of 1935 and '36, both played Norwich and Vermont, as starters. The '35 team also met Bates, then: Brown, Harvard. Yale, William & Mary, Cornell, Princeton and Columbia—losing the last two. The '36 team, after the two easy openers, met: Holy Cross (and lost on an intercepted forward pass), Brown, Harvard. Yale, Columbia, Cornell and Princeton. That latter's a rugged schedule, but it still had the easy opening.

I'm not trying to say who was better than whom. I'm not even prepared to argue that the Williams of 1903 couldn't have whipped the Harvard of 1948. All I'm trying to point out is that not even the supposedly great Dartmouth teams of yore were helmet-to-helmet with their own class from the first game to the last. The Dartmouth 1948 team was, and the coming Dartmouth team will be. The question before the house is whether a team that is, and which drops a couple of close ones, doesn't deserve as many, maybe more, kudos than the units of yore that didn t have to come up for a major test every Saturday.

I'm prepared to argue that it is. In fact, I am arguing it. And, until a better one comes along, quite possibly in this year of Our Lord, 1949, I'm citing you Capt. Dale Armstrong's eleven of 1948 as something truly exceptional. Considering the new set of circumstances in this generally altered world, the football world included, this was one of the finest elevens in all Dartmouth history, and, as above, at the end of its run, one of the best in the country.

It began by losing to mighty Pennsylvania in a scoring fight. Then it ran a supposedly loaded Holy Cross into the discard, 19-6. It exploded, 41-16, against Colgate the next week, and then held its passes against Harvard evidently because they weren't needed, and simply ran the football for a 14-7 win. The next week, it blasted Yale in the Bowl, 41-14, and then whipped Columbia in Hanover, 26-21, in one of the most exciting football games ever seen on Hanover Plain. The next week, in Ithaca, it ran up 26 points on Cornell, but couldn't halt the Cayugans in the fading moments and lost, 27-26. The next week, in a terrific battle in Princeton's Palmer Stadium, it roundly flayed the Bengal, newly-crowned champion of the Big Three, 33-13. The Dartmouth coaches cleaned the bench in the final period, the traditional way of easing the pressure, or, as the coaches say, of calling off the dogs.

In appearance, it was a big team, as teams run in these times. The line averaged close to 200 pounds, with an end squad that ranged from Dale Armstrong's 6:00 to Dave Beeman's 6:04. The tackles were big men-Jon Jenkins was 6:02 and hefted 218. The guard squad was slightly shorter, and lighter although Ray Truncellito was 6:00 and weighed 205. Centers George Schreck and Paul Staley were 5:10 197 and 5:11—191 respectively. The backs were both big and hard-hitting, and medium-sized and fast as lightning.

In action, they were essentially one heavy duty offensive eleven with smoothly interchangeable spare parts, some of them bringing especial skills into play. The work horse of the lot was the 6:01, 193 pound Joe Sullivan who belongs in any list of Dartmouth's true backfield greats. Herb Carey, the 6:00, 205-pound fullback, and next season's captain, furnished driving power. John Clayton, 6:00, 191-pound former Andover captain, and the sophomore quarterback, seems a certain All America off one season's play, and nominee for all-time Dartmouth passing honors, alongside, at least, the practically fabulous Oberlander.

It operated from the T formation, and I don't know how better to describe its interpretation of that mystifying and highly technical collection of interwoven stratagems than by confessing an experience of my own at Princeton. The Green had the ball at midfield and was proceeding satisfactorily when Joe Sullivan took the ball on a play through Princeton's left flank.

I saw him drive into the line, the blocking developed, a hole opened and he shot through for what looked like a long gain, with nothing but blue sky ahead, he slowed perceptibly, after eight or 10 yards, and instead of sidestepping and shooting, he seemed to turn deliberately into a po- tential Princeton tackier.

I thought it a darn funny thing for s player with the drive and know-how of Sullivan to do. Just then, however, I heard a wild scream from the stands looked swiftly in that direction, and there went Johnny Clayton hell bent with the melon. He'd faked the handoff on the line play to Sullivan, had kept possession and had skimmed 35 yards around left end himself. I had looked exactly at the play and I'd have sworn that Sullivan had the football. That's the way this crowd mixed deception and slick ball-handling in with their passes and power, and that's the way they fooled even the scribes in the press terraces.

But, for further details, on. the individual level, as the radio says, consult your daily papers-your next fall's daily papers, that's going to be—because most of these young gentlemen will be back. Only four regulars will be graduated. They're Armstrong, Sullivan, Jenkins and Truncellito. They'll be missed, especially Sullivan, but there are many more waiting, and we had a freshman team. In terms of games won and lost, it wasn't as good a freshman team as we thought it was going to be, but there's some good looking stock on it, and if it survives the exams and other traditional deadfalls, it figures to start to take the requisite polish in spring training.

As final proof that all the above isn't just partisan enthusiasm, I beg leave to sign off with some statistics. First, the honors and awards accorded from outside to the members of the 1948 team:

Captain Dale Armstrong: First N.E.A. All America team; second Grantland Rice All America; first A.P. All Eastern Team; first All New England Team; first Ivy League Team; selected to play for the East in the annual East-West Shrine Bowl Game at San Francisco.

Joe Sullivan: Winner of the George W. (Bulger) Lowe award of the Boston Touchdown Club as New England's outstanding football player of 1948; first AH New England team; second All Ivy League Team; Honorable Mention All Eastern Team; likewise selected to play for the East in the East-West game.

Jon Jenkins: Second All East Team; second All Ivy Team; Second INS All New England Team; Honorable Mention, A.P. All America; selected to play for the North in the annual North-South game at Birmingham, Ala.

Ray Truncellito: Honorable Mention, U.P. All America and A.P. All Eastern Teams; second I.N.S. All New England Team; selected to play for the North in the North-South game.

John Clayton: Honorable Mention, A.P. All America; second All New England and All Ivy Teams. Stew Young: First All Ivy Team; Honorable Mention, U.P. All America.

George Schreck: Second All New England Team; Honorable Mention, All Eastern and All Ivy Teams.

Hal Fitkin: Second All New England Team; First INS All New England; Honorable Mention, A.P. All Eastern.

Red Rowe: Honorable Mention, U.P. All America and A.P. All New England Teams.

That's more off-campus and extraalumni recognition than has come to the members of one Dartmouth team in years, if ever. And the final and supreme clincher that it wasn't misplaced rests in the fact that Armstrong and Sullivan played in the East-West Game; Jenkins and Truncellito in the North-South affair. All four were on the winning side, and all four featured prominently in these contests of especially selected senior stars. In other words, they were as good as the best, if not just a little better.

Off 1948, the drooping Indian seems to have recovered, and to have saddled up again. It looks like a case of Old Men and Cripples Stay Back of the Ropes.

Wah Hoo (Can you hear me now?) Wah Hoo Wah!

BILL CUNNINGHAM '19, author of this football review, shown last month at the Hanover Inn just before settling down to the job of turning out his daily syndicated column for "The Boston Herald."

DARTMOUTH'S LEADING GROUND GAINER, Halfback Joe Sullivan (44), displays his stuff in the Colgate game in Hanover. Ahead of him is Captain-elect Herb Carey (33). Joe starred also in the East-West game.

A STAR FOR 1949? Bob Tyler, sophomore halfback from Niles, Mich., dashes around end fo the Princeton 2-yard line in the 33-13 win at Palmer Stadium which wound up the successful 1948 season.

ONE OF THE TOP COACHES OF 1948, Dartmouth's Tuss McLaughry appears calm, at least outwardly, as the Big Green drives toward another touchdown.

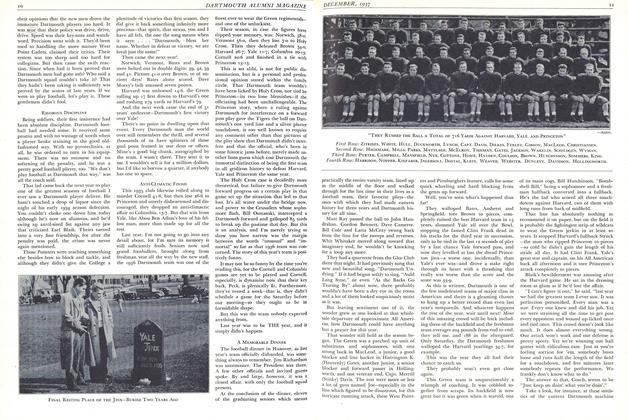

■THIS IS OFFICIAL: A picture of the 1948 football lettermen, likely to be scanned by future Dartmouth gridiron historians, shows (I. to r.) front row—Con Pensavelle, Captain-elect Flerb Carey, Ray Truncellito hafim Dale Armsfrong- Jon Jenkins, Joe Sullivan, Carll Tracy; second row-Larry Perry, Bill Spoor, Jim Melville Dave Beeman, Bill Dey, Hal Fitkin, George Schreck; third row-Dick Gowen, Bill Carpenter, Charlie Bailey, Tom Rowe John Chapman, Stew Young; back row-Assistant Manager Bob Kilmarx, Ted Eberle, Paul Staley, John Clayton, Bob Tyler, Manager Bruce Crawford.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesD. N. A. A.

February 1949 By MAX PRYOR, J. FREDERICK PFAU III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

February 1949 By ROBERT P. FULLER, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

February 1949 By HENRY R. BANKART JR., FREDERICK T. HALEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

February 1949 By OSMUN SKINNER, RUPERT C. THOMPSON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1949 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

February 1949 By DONALD H. STILLMAN, STUART L. MAY

BILL CUNNINGHAM '19

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

November 1941 -

Article

ArticleAND WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

December 1935 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

SportsTHE NEBULOUS IVY LEAGUE

December 1937 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

SportsA MEMORABLE DINNER

December 1937 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Books

BooksWINGS IN THE NIGHT

November 1938 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Article

ArticleWOMEN OF DARTMOUTH

February 1944 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19