Prerequisite of Courses with Charles Ernest Bolser, Versatile Veteran of Chemistry Faculty, Is Work Well Done

ON A NIGHT somewhere in the last years of the Eighteen-Eighties the writer, a small boy, was lifted up to a window to look out over a roaring Inferno that once had been Carriage Hill in Amesbury, Massachusetts. The fire had come during church services, on a Sunday evening, when most of the townsfolk, listening to ministers, were suddenly startled by the shrieking of locomotive whistles and the siren on Babcock's Factory. Rushing to the street, pastors and congregations found themselves in a confused crowd rushing Square-ward into Elm Street, where bloodred flames were leaping into the air. From building to building the fire spread, windows cracking all along the street, with beams and chimneys crashing to the ground the livelong night. In the morning, the carriage district was a desolate, smoking ruin. The great age of Amesbury carriages had come almost to an end.

But on the road to the Ferry, where once George Washington crossed over to New buryport, there stood for many years after the fire a large wooden building which bore a sign across the front:

NEAL AND BOLSER

Out of this Bolser family of carriagemakers came Charles Ernest. And incidentally out of the other family, the Neals, came a Dartmouth man Cleland Neal of the class of 1903. But this story deals with the Bolsers who shared the joy of craft and high exactitude of the carriage men of the Seventies and Eighties. There was an insistence of perfection in that trade, a serious intent upon skill, and a man to gain a place in it must work hard and long and above all things, his work must be well done. New England towns possessed also, then as today, a demand for culture, and there were reading groups and "music" circles, with here and there a poet such as John Greenleaf Whittier, an artist such as Charles Davis, and a musician like Elizabeth Hume.

"It was a relative Rear Admiral John R. Eastman of the Naval Observatory in Washington, himself a former trustee of Dartmouth, who headed Bolser to Hanover. When he reached the college, after his schooling in the High School, which had succeeded the old Academy, he found it still a college on a hill, a place of learning intermixed with cane rushes, salt rushes, football rushes, flag rushes, and horning bees. Yet there was something new in the Dartmouth air. Dr. William Jewett Tucker was coming that fall from Andover to become head of the "Small College,"—a new era was beginning. In college, Bolser took an interest in Chemistry and won honorable mention in that subject in his junior year. At that same time he was elected captain of the track team, his specialty being the half-mile, in which he held the New England Intercollegiate record.

His interest in athletics, strong at that period, remained so during all his teaching years, and in addition to serving 18 years on the College Athletic Council, and assisting in bringing the recreational program up to its present efficiency, he took part in exercise which did not interfere with his work, such as tennis and swimming. He was a hard runner, his mates say, in the days before specialized training was invented. He ran himself out on one or two occasions, and was so interested in running a race in the old B. A. A. building in Boston, one time, that he ran clear over the top of a sloping wooden corner, and went head-first down a flight of stairs into a dressing room in the basement.

College finished, a short term of teaching at North Berwick, Maine, and then three years in Germany. Because in those days, Chemistry in American institutions was in its infancy, it was necessary to pursue higher courses abroad. At the University of Goettingen he became a candidate for the Ph.D. degree, with Chemistry as a major subject, and Physics and Mathematics as minors. Three years of study there brought not only the degree and the work it implied, but an acquaintance with Germans of all classes and foreign students who regarded German Universities as Chemistry Meccas. The period in residence might have been shorter, but was lengthened somewhat by the fact that theT significant results of a research-problem which he had well under way were obtained independently and published by another worker. When he came back to New York he found himself so steeped in academic thought and German background that when he went to call for a cab at the Battery in New York he discovered that he had forgotten the English word for cab and had to get someone to supply him with it.

This was in 1901. That same year he came to Hanover to take up his work of teaching. He began in that "modified log cabin," Culver Hall, that once stood on East Wheelock Street behind the Fayerweathers. The department of Chemistry consisted in 1901 of Professor E. J. Bartlett, Dr. C. H. Richardson, Dr. Bolser, and Mr. L. B. Richardson. Ever serious so far as work was concerned, Dr. Bolser had then, as now, a quick sense of humor, quite independent too, in its own way. In the early days he found himself quartered for classes in a room beneath that in which Professor Charles F. Richardson was teaching American Literature, and noted from time to time the "wooding up" which made the floors rock a little. He paid no attention to this, however, until one day when an unusually violent stamping brought down plaster which seriously interferred with his Chemistry. Immediately the word went out to the students that the next experiment was the making of some pungent compound, the formula for which has been lost during the course of years. As the fumes ascended to the third floor, there came a gradual diminution of "wooding up," and then at the point when the experiment was at its height, the doors of the class room above burst open, and down the stairs came rushing and leaping the students of American Literature with but one thought in mind,—fresh air.

Finally, like the captain who is last to leave his ship, the dignified professor descended.

"Good morning," said the Chemistry instructor seriously.

"Clothespins" Richardson stared at him. "That's the worst stink I ever smelled," he said, and turned away.

With the increase in the number of students taking Chemistry, Dr. Bolser's work grew. He has always had a class of first year men in Organic Chemistry, but most of his work has been with advanced men or medical students. "To know facts is not enough," is one of his principles,—"one must have reverence for facts." And he insists that his men be punctual. To medical students he says: "If you are called to see a patient you want to get there before you meet the undertaker coming out." And he has always insisted that his students write correct English. Once a youth who thought that he had done well in a Chemistry Exam called in crestfallen mood to inquire the meaning of a D. "Isn't my Chemistry all right?" The professor looked at him: "Your Chemistry may be all right if you know enough about the English language to express yourself. I'd advise that you take a course or two in English." To another student who simply hadn't the ability to spell, he said: "There may be, outside of my knowledge, some excuse for spelling gas gass, but when you spell it in the plural as gassess, it simply effervesces."

Thirty-eight years of teaching at Dartmouth! The same exacting requirement made by the carriage builder of the men under him marked this teaching. "There is no excuse for a man's not doing his work well," he always says. Emphasis to this was added of course by the thoroughness of the studies in Germany. In the work of a teacher, it is hard to guage results,—hundreds of men go through a teacher's courses with the passing of years, and some are brilliant and some develop brilliancy, but just how much is due to the teaching of any one man it is hard to tell. Certainly Dartmouth has sent some brilliant men into the field of Chemistry, though for them the modest professor will take no personal credit. With the removal of the Department of Chemistry to Steele in later years, Dr. Bolser's responsibilities increased as well. He had been a pioneer in chem- ical blood-analysis, and now hospital duties were added to those of the College and Medical School. He was writing constantly, reviews, articles, laboratory manual, and preparing talks now and then for professional meetings.

But the main job was his teaching. He had begun as a teacher, and the emphasis of his work lay in that direction. "Most research today is done in specialized groups or foundations," he says. "In our laboratories we do work out problems now and then, but we are most interested in the men who come under us. It is the teacher's influence upon the student that counts the most and is the most important.

OUTING CLUB PIONEER

Yet beside the teaching, he has done the most within his power to promote the fortunes and good name of his college. The work on the Athletic Council was but a part of it. As a former member of the Outing Club Council he sat in at meetings in early days when the Club was just getting under way. One pleasant memory out of the long ago is that a suggestion of his that Carnival guests as well as competitors should spend some time outdoors and not so much on the dance floor was taken up and gradually evolved into the Outdoor Evening. Out of this same Council came the name Cabin and Trail. He has also done much speaking to Alumni groups, that feature of the college in which members of the faculty meet members of the Alumni at monthly or semi-annual meetings.

Insistence upon work well done, the creed of the carriage-builders. And without respect to persons, either. There was a certain student in years gone by who came up after a lecture and voiced a request to have his seat in class changed. The professor looked over the list and saw that he was seated next to a negro. Quick as a flash,and his retorts come that way, marked somehow by an independent snap, "I'll change your seat young man when you get better grades than that colored man sitting next to you." The white boy never changed his seat. And the professor in the classroom is always the professor, and the student is always the student. "Your suit is just like mine," a boy once said to him. The retort came. "No. Yours is just like mine."

Thirty-eight years on duty as instructor, assistant professor and professor, except for two sabbatical leaves. In that time his own mental relaxation has been: wide reading, the study of languages, summer travel, the usual lectures, concerts, and plays of a college town and the cities nearest-by. Yet to him nothing is easy,—ease itself is only accomplished by labor and drudgery. There is no short cut to learning, no accomplishment worth while that is not, for a time at least, subject to effort and thought and patience. A hobby of his, the keeping of bees, brought much comment from his mates. "Don't you get stung sometimes?" he was asked. "Yes, but that's nothing when you're immune," was the reply "How many times must you be stung before you're immune?" Dr. Bolser shot back "I don't know. Perhaps 200."

WORK., NOT HOBBIES

It's quite fashionable these days to have a hobby. Indeed the word is so popular that in certain circles it's fatal not to have one. A hobby is "a small Old World falcon." Then again it is a "strong, medium-sized horse." After that it becomes an "engrossing topic." One takes one's pick—raising falcons, or riding strong horses, or engaging in engrossing topics. Or one might say casually, with devastating effect, "Life's my hobby." It is not possible to associate the word "hobby" with the work of certain men, Dr. Bolser among them, particularly. If he engaged for 18 years as member and chairman of the council on athletics, it was just as much a duty, as was his work in the laboratory. If he kept bees it was attended to as seriously, say, as his work on the chemical constituent of the water in the Spaulding Pool. Incidentally, not only is the chemical constituent of the pool, a concern of his, and officially too, but he makes test of the proof by swimming in it almost every day.

So in the laboratory, the tubes are filled, the apparatus is set up, and soon the bub- bling compound is created. It is however not a compound of hit-or-miss quality, it is a compound that is the result of law, a law based upon such facts as the human race knows and has proven. To the ac- curacy of such laws the chemist bows,—in application, that compound may cure dis- ease, it may create new forms of energy, it may lead to some startling discovery which determines the place of man in a mysteri- ous universe. But this is the machinery. The mind that is its master .is the man. The man has qualities which no compound possesses,—justice, that law of the mind that gives due praise or censure. There is humor which saves the world from over- seriousness, the only known agent to re- duce the friction of nerves. There is inter- est, the desire to impart knowledge, loyalty to work and institution; independence, without which man is but a cipher. The college student looks eagerly for these things. Teaching is of little use without them, no matter how able or famous in his own field of work the teacher may be. • • • • In this case he finds them.

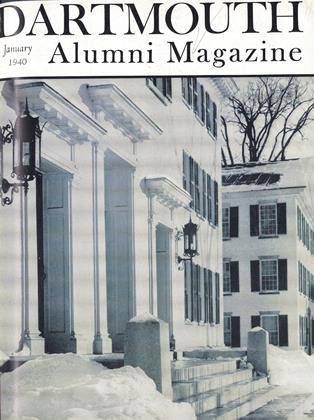

CHARLES ERNEST BOLSER For 38 years a strong influence in the faculty for scientific study of a high order of accuracyand diligence.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOld Grad Looks At Siwash

January 1940 By FRANCIS M. QUA '11 -

Sports

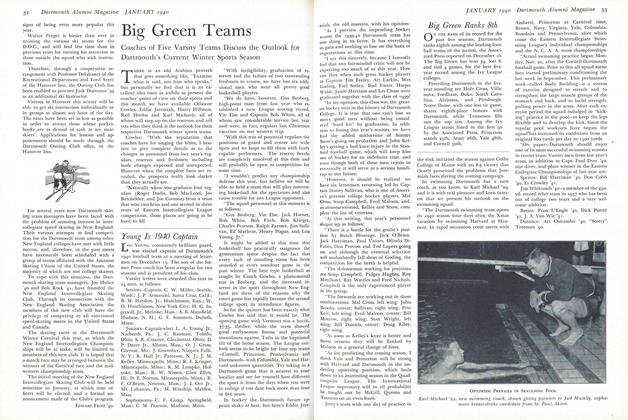

SportsBig Green Teams

January 1940 -

Article

ArticleThe College In The Sixties

January 1940 By DR. WILLIAM LELAND HOLT -

Article

ArticleCameos of a Crisis

January 1940 By ALAN L. STROUT '18 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

January 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

January 1940 By ERNEST H. EARLEY

ERIC P. KELLY '06

-

Article

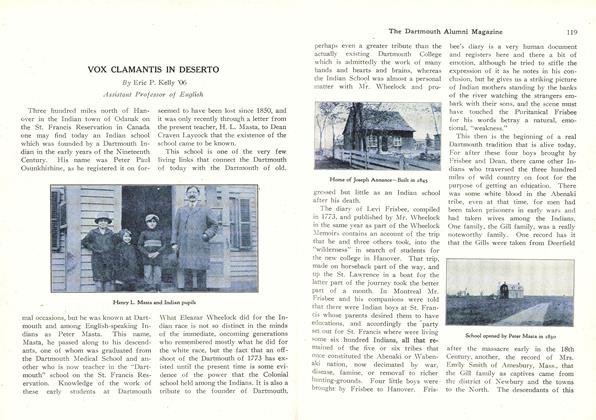

ArticleVOX CLAMANTIS IN DESERTO

December 1924 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Article

ArticleWAS THE PROFESSOR RIGHT?

June 1935 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksTHE NEW YORK TRIBUNE SINCE THE CIVIL WAR

February 1937 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Article

ArticleAn Important and Unusual Career

February 1938 By ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Article

ArticleOur Debt to Vanessa

June 1952 By ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Article

ArticleHe Makes Students Think

December 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22, ERIC P. KELLY '06