Dr. Connor, Medical School '01, Destroyed the Plague In Ecuador and Earned Immortal Fame

No MAN IN HISTORY has done more in the elimination of yellow fever than he."

Officially adopting this statement made by a colleague, the scientific directors and the staff of the International Health Division of the Rockefeller Foundation recently paid tribute to Dr. Michael Edward Connor, Dartmouth Medical School 'ox, whose death was reported in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE last month.

One of the greatest actors in the drama of western hemisphere friendship, Dr. Connor, as a young medical officer promoted from the ranks, started his attack on the feverous diseases of South America in Panama, when the United States assumed construction of the Canal. General W. C. Gorgas requested his service. "You have a knack for sanitary work," the general said, and the youthful doctor, scarcely out of college, though experienced with two years' health duties in the Philippine Islands, joined Gorgas' staff in the eradication and prevention of yellow fever and other tropical diseases.

Until the World War blazed in Europe, he served as a health officer in the Canal Zone and countries of the Isthmus. He met his wife while she was a nurse in the Ancon hospital, to which he was attached, and married her in 1906. After his government position, he undertook special sanitary surveys for commercial organizations operating in South America, and outlined for these companies programs directed toward the control of malaria, yellow fever and bubonic plague.

It was in 1916, however, at the age of 37, that his great practical contribution to hemisphere friendship began.

Joining the staff of the International Health Division, then the International Health Board, unit of the Rockefeller Foundation, he accepted duties which eventually took him to almost all the countries of South America, where yellow jack, among dozens of swamp and tropical diseases, took devastating toll of native life. His first Division assignment was investigation of health conditions in Central America, Jamaica, and also the state of Georgia.

Then came the inspiring clean-up of Ecuador and Guayaquil, the capital which at one time lost half its 100,000 population from the fever. Salesmen would not visit this city, they sold goods by mail; foreigners, if they did come, died by the hundreds; ship captains would often put into port and find themselves stranded because of deaths among the crew.

In the clinical words of the Foundation's report of the Dartmouth graduate's work: "In November, 1918, Dr. Connor was sent to Guayaquil to inaugurate measures for the eradication of yellow fever. At that time yellow fever was epidemic in Guayaquil and had been present there more or less continually for a long period of years. By June, 1919, however, the disease was under complete control and it was officially announced in July, 1920, by the Director of Health of Ecuador that yellow fever had been entirely eradicated from the country.

"Since then, no vestige of it has ever reappeared in Guayaquil or along the Ecuadorean coast. In recognition of his valuable contribution toward the control of disease in the country, Dr. Connor was awarded the highest decoration conferred by the Ecuadorean Government. He also received many other expressions of gratitude."

This epic task was followed by surveys, studies and fever control measures in Colombia, Peru, Mexico, Dutch and British Guiana, Salvador and other Central American countries. For four years, until he re signed from the Division in 1930, he was in charge of the yellow fever program in Brazil.

Dr. Connor's efforts were not merely technical. His fellow-worker and chief for several years, Dr. F. F. Russell, has recognized him as an example of what can be done in public health education by diplomatic methods.

"I have been over the area," Dr. Russell said, "and have some idea of the difficulties encountered, both from the nature of the problem itself and because the campaign involved intimate personal relationships with all householders in the areas under surveillance. It is astonishing, in face of such difficulties, that so much good work could have been done."

Wherever Dr. Connor went, as a sort of medical ambassador of good will, he overcame the native's fear that the United States wanted imperial power; cured them of their belief that yellow jack was preferable to cooperation with the United States; and generally persuaded the natives, not just their governments, to work with him and with each other. Playgrounds, libraries, schools, in addition to modern sewage and water systems, came to be visible proof of his diplomatic successes.

Born in 1879 at Amesbury, Mass., he was inspired to become a physician by the town doctor. Although his parents thought him too young to enter Dartmouth at 17 years of age, the town doctor helped him win the decision, and he worked his way through Dartmouth, graduating from the Medical School when 21. He spent six months as interne in the Fanny Allen Hospital at Burlington, Vt., and later served for a short period in the outpatient rooms of the Boston City Hospital, before going to Denver, Col., to set up a private practise. He entered the Army in 1902.

News of his death reaching Guayaquil, which is proud of its paved Connor Street, the department of health voted him homage, and in New Orleans (where he had recently been adviser to the United Fruit Cos.) the local consul called him "pioneer in the development of a cordial feeling for the United States in Ecuador." The Rockefeller Foundation issued a special bulletin of commendation.

DR. MICHAEL E. CONNOR Graduate of the Dartmouth MedicalSchool in IC/OI who died Sept. 6. Heachieved medical fame in his handling ofyellow fever in the Republic of Ecuador.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSocial Idealism in College

December 1941 By ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

December 1941 By Frank Hall '41 -

Article

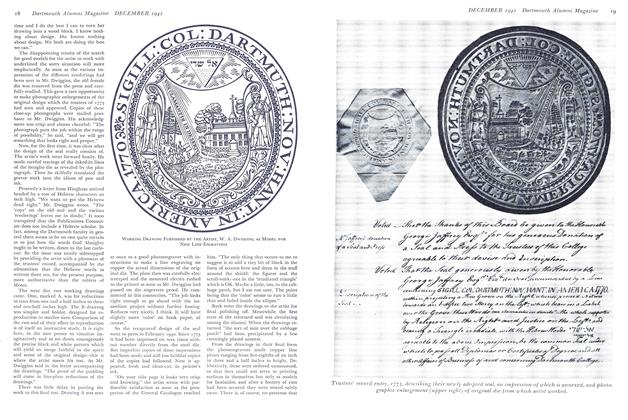

ArticleRediscovering the College Seal

December 1941 By RAY NASH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937*

December 1941 By DONALD C. MCKINLAY, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

December 1941 By CONRAD E. SNOW, RICHARD C. PLUMER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919*

December 1941 By WINDSOR C. BATCHELDER, MAX A. NORTON

Article

-

Article

ArticleMusical Clubs Trip

APRIL 1928 -

Article

ArticleProgram NINETEENTH ANNUAL WINTER CARNIVAL DARTMOUTH OUTING CLUB, HANOVER, N. H.

FEBRUARY 1929 -

Article

ArticleLetters and Opinions Solicited for Forum on Future of the Liberal College

May 1943 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

February 1950 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

April 1957 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

November 1959 By EDWARD S. BROWN '35