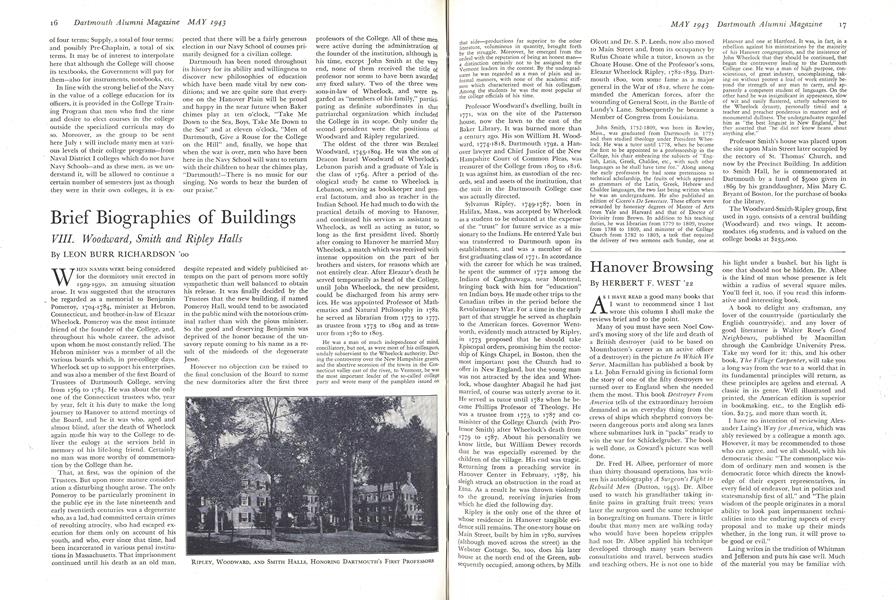

VIII. Woodward, Smith and Ripley Halls

WHEN NAMES WERE being considered for the dormitory unit erected in 1929-1930, an amusing situation arose. It was suggested that the structures be regarded as a memorial to Benjamin Pomeroy, 1704-1784, minister at Hebron, Connecticut, and brother-in-law of Eleazar Wheelock. Pomeroy was the most intimate friend of the founder of the College, and, throughout his whole career, the advisor upon whom he most constantly relied. The Hebron minister was a member of all the various boards which, in pre-college days, Wheelock set up to support his enterprises, and was also a member of the first Board of Trustees of Dartmouth College, serving from 1769 to 1784. He was about the only one of the Connecticut trustees who, year by year, felt it his duty to make the long journey to Hanover to attend meetings of the Board, and he it was who, aged and almost blind, after the death of Wheelock again made his way to the College to deliver the eulogy at the services held in memory of his life-long friend. Certainly no man was more worthy of commemoration by the College than he.

That, at first, was the opinion of the Trustees. But upon more mature consideration a disturbing thought arose. The only Pomeroy to be particularly prominent in the public eye in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was a degenerate who, as a lad, had committed certain crimes of revolting atrocity, who had escaped execution for them only on account of his youth, and who, ever since that time, had been incarcerated in various penal institutions in Massachusetts. That imprisonment continued until his death as an old man, despite repeated and widely publicised attempts on the part of persons more softly sympathetic than well balanced to obtain his release. It was finally decided by the Trustees that the new building, if named Pomeroy Hall, would tend to be associated in the public mind with the notorious criminal rather than with the pious minister. So the good and deserving Benjamin was deprived of the honor because of the unsavory repute coming to his name as a result of the misdeeds of the degenerate Jesse.

However no objection can be raised to the final conclusion of the Board to name the new dormitories after the first three professors of the College. All of these men were active during the administration of the founder of the institution, although in his time, except John Smith at the very end, none of them received the title of professor nor seems to have been awarded any fixed salary. Two of the three were sons-in-law of Wheelock, and were regarded as "members of his family," participating as definite subordinates in that patriarchal organization which included the College in its scope. Only under the second president were the positions of Woodward and Ripley regularized.

The oldest of the three was Bezaleel Woodward, 1745-1804. He was the son of Deacon Israel Woodward of Wheelock's Lebanon parish and a graduate of Yale in the class of 1764. After a period of theological study he came to Wheelock in Lebanon, serving as bookkeeper and general factotum, and also as teacher in the Indian School. He had much to do with the practical details of moving to Hanover, and continued his services as assistant to Wheelock, as well as acting as tutor, so long as the first president lived. Shortly after coming to Hanover he married Mary Wheelock, a match which was received with intense opposition on the part of her brothers and sisters, for reasons which are not entirely clear. After Eleazar's death he served temporarily as head of the College, until John Wheelock, the new president, could be discharged from his army services. He was appointed Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy in 1782. he served as librarian from 1773 to 1777, as trustee from 1773 to 1804 and as treasurer from 1780 to 1803.

He was a man of much independence of mind, conciliatory, but not, as were most of his colleagues, unduly subservient to the Wheelock authority. During the controversy over the New Hampshire grants, and the abortive secession of the towns in the Connecticut valley east of the river, to Vermont, he was the most important leader of the so-called college party and wrote many of the pamphlets issued on that side—productions far superior to the other literature, voluminous in quantity, brought forth by the struggle. Moreover, he emerged from the ordeal with the reputation of being an honest man a distinction certainly not to be assigned to the Vermont leaders in the contest. By the undergraduates he was regarded as a man of plain and informal manners, with none of the academic stiffness which characterized most of his colleagues. Among the students he was the most popular of the college officials of his time.

Professor Woodward's dwelling, built in 1771, was on the site of the Patterson house, now the lawn to the east of the Baker Library. It was burned more than a century ago. His son William H. Woodward, 1774-1818, Dartmouth 1792, a Hanover lawyer and Chief Justice of the New Hampshire Court of Common Pleas, was treasurer of the College from 1805 to 1816. It was against him, as custodian of the records, seal and assets of the institution, that the suit in the Dartmouth College case was actually directed.

Sylvanus Ripley, 1749-1787, born in Halifax, Mass., was accepted by Wheelock as a student to be educated at the expense of the "trust" for future service as a missionary to the Indians. He entered Yale but was transferred to Dartmouth upon its establishment, and was a member of its first graduating class of 1771. In accordance with the career for which he was trained, he spent the summer of 1772 among the Indians of Caghnawaga, near Montreal, bringing back with him for "education" ten Indian boys. He made other trips to the Canadian tribes in the period before the Revolutionary War. For a time in the early part of that struggle he served as chaplain to the American forces. Governor Wentworth, evidently much attracted by Ripley, in 1773 proposed that he should take Episcopal orders, promising him the rectorship of Kings Chapel, in Boston, then the most important post the Church had to offer in New England, but the young man was not attracted by the idea and Wheelock, whose daughter Abagail he had just married, of course was utterly averse to it. He served as tutor until 1782 when he became Phillips Professor of Theology. He was a trustee from 1775 to 1787 and cominister of the College Church (with Pro- fessor Smith) after Wheelock's death from 1779 to 1787. About his personality we know little, but William Dewey records that he was especially esteemed by the children of the village. His end was tragic. Returning from a preaching service in Hanover Center in February, 1787, his sleigh struck an obstruction in the road at Etna. As a result he was thrown violently to the ground, receiving injuries from which he died the following day.

Ripley is the only one of the three of whose residence in Hanover tangible evidence still remains. The one-story house on Main Street, built by him in 1780, survives (although moved across the street) as the Webster Cottage. So, too, does his later house at the north end of the Green, subsequently occupied, among others, by Mills Olcott and Dr. S. P. Leeds, now also moved to Main Street and, from its occupancy by Rufus Choate while a tutor, known as the Choate House. One of the Professor's sons, Eleazar Wheelock Ripley, 1782-1839, Dartmouth 1800, won some fame as a major general in the War of 1812, where he commanded the American forces, after the wounding of General Scott, in the Battle of Lundy's Lane. Subsequently he became a Member of Congress from Louisiana.

John Smith, 1752-1809, was born in Rowley, Mass., was graduated from Dartmouth in 1773 and then studied theology under President Wheelock. He was a tutor until 1778, when he became the first to be appointed to a professorship in the College, his chair embracing the subjects of "English, Latin, Greek, Chaldee, etc., with such other languages as he shall have time for." Along among the early professors he had some pretensions to technical scholarship, the fruits of which appeared as grammars of the Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Chaldee languages, the two last being written when he was an undergraduate. He also published an edition of Cicero's De Senectute. These efforts were rewarded by honorary degrees of Master of Arts from Yale and Harvard and that of Doctor of Divinity from Brown. In addition to his teaching duties, he was librarian from 1779 to 1809, trustee from 1788 to 1809, and minister of the College Church from 1782 to 1805, a task that required the delivery of two sermons each Sunday, one at Hanover and one at Hartford. It was, in fact, in a rebellion against his ministrations by the majority of his Hanover congregation, and the insistence of John Wheelock that they should be continued, that began the controversy leading to the Dartmouth College case. He was a man of high purpose, conscientious, of great industry, uncomplaining, taking on without protest a load of work entirely beyond the strength of any man to carry, and apparently a competent student of languages. On the other hand he was insignificant in appearance, slow of wit and easily flustered, utterly subservient to the Wheelock dynasty, personally timid and a teacher and preacher ponderous in manner and of monumental dullness. The undergraduates regarded him as "the best linguist in New England," but they asserted that "he did not know beans about anything else."

Professor Smith's house was placed upon the site upon Main Street later occupied by the rectory of St. Thomas' Church, and now by the Precinct Building. In addition to Smith Hall, he is commemorated at Dartmouth by a fund of $5000 given in 1869 by his granddaughter, Miss Mary C. Bryant of Boston, for the purchase of books for the library.

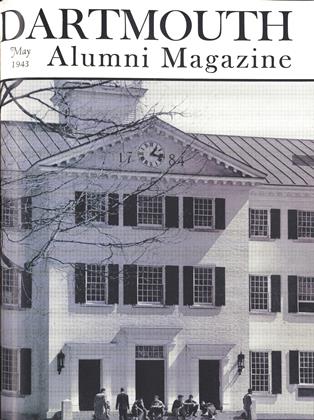

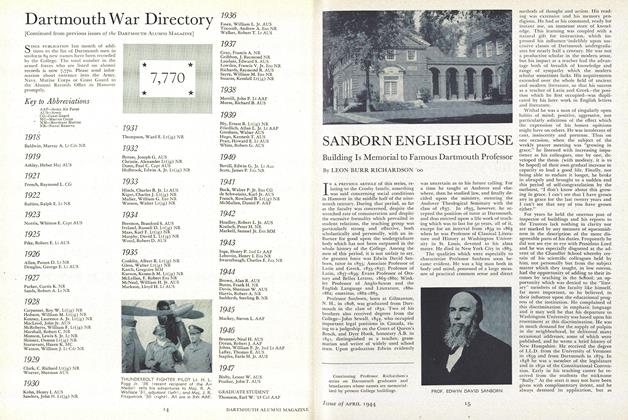

The Woodward-Smith-Ripley group, first used in 1930, consists of a central building (Woodward) and two wings. It accommodates 169 students, and is valued on the college books at $235,000.

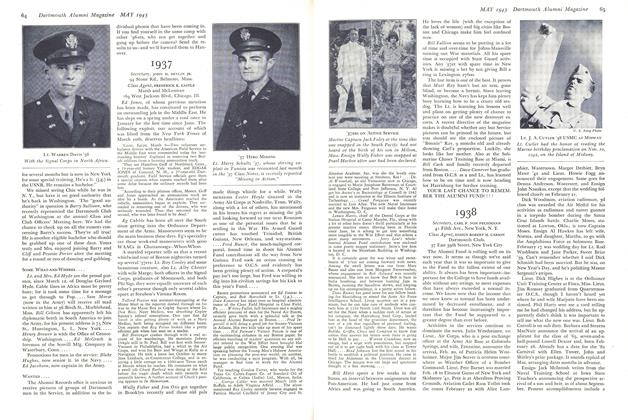

RIPLEY, WOODWARD, AND SMITH HALLS, HONORING DARTMOUTH'S FIRST PROFESSORS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1943 -

Article

ArticleTHE LIBERAL ARTS COLLEGE

May 1943 By W. H. COWLEY '24 -

Article

ArticleFrom the Mailbag

May 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

May 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FREDERICK K. CASTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

May 1943 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., KARL W. KOENIGER

LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00

-

Article

ArticleUseless Dartmouth Information

February 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

April 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

June 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleSANBORN ENGLISH HOUSE

April 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleLORD AND GILE HALLS

June 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleThis Our Purpose

June 1950 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00