IF I TRY TO remember David as I knew him, as my mentor and colleague for twenty-nine years, perhaps I shall touch a chord in the memories of some of the alumni who knew him too.

In 1919-1920 David had oversight of all the upperclass writing courses, of which there were five, and himself taught in three, besides teaching an upperclass literature course. It was an extremely heavy teaching load, but he carried it with a matchless vigor and grace. One of those courses, the most advanced, met in the evening at his home, then Judge Brown's house on Rope Ferry Road, and there David was at his best. In those days he was black-bearded, lean, quick in speech and movement. He loved being host—he never seemed really comfortable as a guest—and he thoroughly enjoyed the company f young men. We made a circle of intent faces, for we all had part in the evening's work and fun with David to lead us. I remember the .firelight on his glasses, so like the flashing light from his mind, as we discussed the stories, plays, poems, essays which the class brought to these meetings —none of them imperishable works of art, perhaps, but all of them treated by him with respect and sympathy, the resp.ect and sympathy which young would-be writers need and must find if they are to benefit from writing. Teaching writing is intimate; the youngster lays himself bare; he wants approval but not approval too easily won. David's delicacy of judgment, his instinctive tact, his keen discernment of capacity in the student, together with his wide knowledge of the directions contemporary writing was taking, made him a model teacher of writers.

In 1915 David had begun editing a magazine called The Third Rail, whose contributors were all members of his writing classes. It appeared at somewhat irregular intervals, usually four or five times a year. It was neatly printed on good paper, and was financed by a "laboratory fee" of only $2 from each member of the course, though it also had a small public sale at ten cents a copy and a few local advertisements. It s too bad that in our contemporary economy little magazines like TheThird Rail can no longer be published without more subsidy than that. What a good magazine The Third Rail was! I have just looked over the issues preserved in the Archives in Baker Library and I find there, signed to articles and stories and plays, many names well known among Dartmouth alumni. Some, by now, are established professional writers; a few are in government; one, at least, is prominent in motion pictures; many are successful in business; most of the names I knew, however, are those of teachers. I wonder how many of the men who contributed to TheThird Rail first had there the thrill of seeing their work in print. And apparently The Third Rail excited some public response. One advertiser took the whole back page of an issue to say: "Buy a THIRD RAIL for yourself or your friend. If either of you fails to get at least three (3) brand new ideas from it after a careful reading, come down to Dudley's and we'll buy the copy back from you."

That ad must have pleased David, because "ideas" excited him. He was always trying to find them, asking for them from his students and his colleagues, trying to give them shape and effect, as well as generating them himself. By "ideas" he meant, I think, not only philosophical notions, or the departures from tradition or attacks upon it which so readily tempt the young, but also fresh ways of doing old things: in writing, for instance, what the reporter calls the "new angle"; in teaching, the novel organization of familiar material, or the insight which sheds new light.

David had that most precious gift of a teacher, the ability to make his classes gay. We teachers all seem to fail: what we teach is forgotten, even how we teach is forgotten, and if what we do lasts at all, it lasts by the spirit. And the spirit springs more from what we are and how we live than from what we know or have done. Yet David was unusual, both in what, he knew and had done. His ancestry was distinguished old American, but he was born in Shanghai and lived his first sixteen years in China and Japan. He had lived and worked north, south, east, and west in the United States, and also for some years in Brazil. Between the wars he traveled widely in Europe. His knowledge of literature, especially fiction and criticism, was both wide and ripe. He knew architecture, and when he built his home he made the complete plans for it. He had a considerable part in planning Sanborn House, still probably the best accommodation provided any English Department in the country. But I think David would wish to be valued not so much for his attainments and accomplishments as for what he was as he lived and taught.

As the years went by, he became more of a bon vivant; he grew heavier and slower in movement; the beard became bigger and whiter; he drove the famous white Packard. His striking appearance, no doubt carefully cultivated, I think he thought helped him to teach, helped him not only to gain and keep attention, but to make what he said impressive and memorable. And I think none of his students or colleagues found his appearance a barrier. He was always accessible.

But little do or can the best of us: That little is achieved through Liberty.

Who, then, dares hold, emancipated thus,

His fellow shall continue bound? Not I, Who live, love, labor freely, nor discuss A brother's right to freedom. That is "Why."

Perhaps this is dangerously individualistic doctrine. It undoubtedly has an old fashioned air in these days when education tends more and more to prescription and standardized requirement. But I think David's liberalism worked.

Yet his outstanding quality, as I saw him, was imagination. I think the war was very hard on him because he lived it too intensely in his imagination. His imagination explained his ability to respond so keenly to literature; it made him able to detect and bring forth the best in his students. He had the defect of the quality, too, in his tendency to see blacks and whites where there were only grays, though in the long run his judgment was cool and his discernment sound. His imagination made him so charming a host, as it had enabled him to create the delightful home in which he could be host.

David is dead. He taught in Dartmouth College for thirty-five fruitful years, and I think he is glad that he remained teaching to the end. The students and colleagues who knew him will remember him, for he was an unforgettable man.

THE LATE PROF. DAVID LAMBUTH

AN OLD PHOTO OF NATHAN SMITH is examined by Dean Rolf C. Syvertsen 'lB, Dr. Frederic P. Lord '9B, and Dr. John F. Gile 'l6.

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

David Lambuth, Professor of English, died in Hanover, August si, of a cerebral hemorrhage. One of the senior members of the Dartmouth faculty, he was 69 years old and was on the eve of retirement this coming year. Professor Lambuth had taught at Dartmouth since 1913 and had held the rank of full professor since 1920. A graduate of Vanderbilt, he did advanced work at Columbia and Oxford, and before coming to Hanover taught at Vanderbilt and Granberry College in Brazil. Surviving him are his widow, the former Myrtle Spindle of Harrisonburg, Va., and a daughter, the wife of Prof. Kenneth A. Robinson of the Dartmouth English Department.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleShould the Athlete Rate a Preference?

October 1948 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. '36 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1948 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD, ROBERT P. BURROUGHS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

October 1948 By E. PAUL VENNEMAN, HERBERT F. DARLINC, ROBERT M. STOPFORD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

October 1948 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

October 1948 By HENRY K. URION, RALPH D. PETTINGELL, HENRY B. VAN DYNE

BENFIELD PRESSEY

-

Books

BooksYES, MY DARLING DAUGHTER.

June 1937 By Benfield Pressey -

Article

ArticleHollywood at Work

November 1938 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Books

BooksTHREE SOUTHWEST PLAYS, including WHERE THE DEAR ANTELOPE PLAY,

April 1942 By Benfield Pressey -

Books

BooksTHESE WERE ACTORS.

January 1956 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

FeatureFive Wishes for America

By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Books

BooksSTUDIES IN THE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE DRAMA.

MAY 1959 By BENFIELD PRESSEY

Article

-

Article

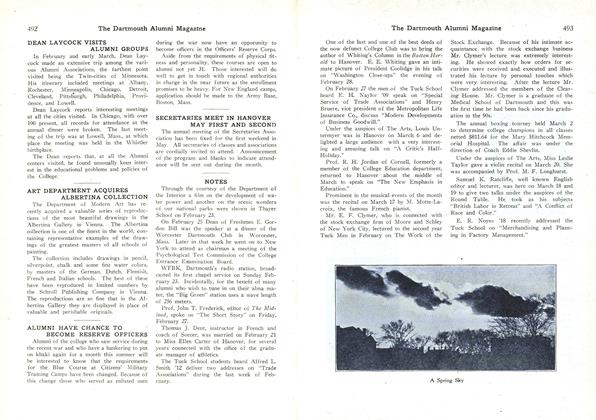

ArticleUNDERGRADUATES IN WAR SERVICE

June 1917 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI HAVE CHANCE TO BECOME RESERVE OFFICERS

April, 1925 -

Article

Article"What Do You Like?"

November, 1930 -

Article

ArticleYE GLORIOUS SPORT OF RUSHING

November, 1930 -

Article

ArticleChampions of Water Polo

APRIL 1997 -

Article

ArticleNuremberg Club

February 1946 By Robert R. Rodgers '42