By Russell A.Fraser '47. London: Routledge & KeganPaul, 1962. 184 pp. 30s.

On page 139 of this book Professor Fraser defines Shakespeare's poetics as "the underlying principles which sustain Shakespearean drama," and which, he says, "remain constant throughout his career in the theatre." These are not principles of rhetoric or structure, as might be inferred from the parallel to Aristotle's Poetics, but principles of conduct, values, ethical discriminations, which Shakespeare absorbed and held as a Renaissance man from the intellectual and moral climate of his age. Professor Fraser aims to show how these principles, particularly as shown in emblems contemporary with Shakespeare, are advocated in the plays.

Everyone who has studied King Lear has been impressed, I suppose, by Shakespeare's effort to keep the play, on the surface, pagan. God is always the gods, and unperceptive critics have been fond of citing "As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods/They kill us for their sport" as the play's pagan motto and central meaning. But even superficial readers must have been dissatisfied with this judgment, for the play has so often strangely left readers and viewers com- forted rather than depressed. Professor Fraser's work goes far to explain why.

King Lear, he shows, exposes Shakespeare's confident sharing in the beliefs of his age: that Providence (God) rather than Fortune (Chance, accident, the quarreling gods) rules events and men; that a man must obey his Kind (his given nature) or Providence will bring him to adversity; that order ordained by God in Nature and Man is the highest value, and the worst of men is the anarch, the subverter. Lear, in seeking to retain the ceremony and privilege of king without ruling, is anarch, and Providence must humiliate him. Goneril and Regan and Edmund are anarch in subverting the family obligation and must be destroyed. The will leads men astray unless subjected to reason, which will help in discriminating between show and substance. Redemption is possible, however, even to the greatest sinner, by God's grace. "Lear puts on the new man."

Professor Fraser exhibits these principles by wide-ranging literary and iconographic reference. His plates, fifty-three in all, support his thesis and also arouse lively curiosity about elements no doubt irrelevant to the thesis. Though I should disagree with Professor Fraser about the differences between tragedy and comedy, I think this is a very good book.

The work is gracefully dedicated to the late Prof. George Frost '21.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePOETRY AT DARTMOUTH

March 1963 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Feature

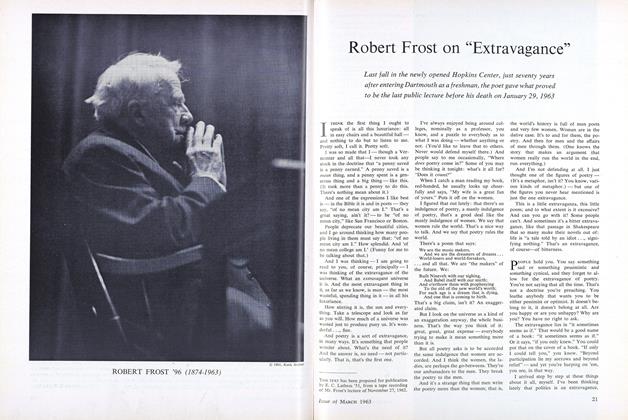

FeatureRobert Frost on "Extravagance"

March 1963 -

Feature

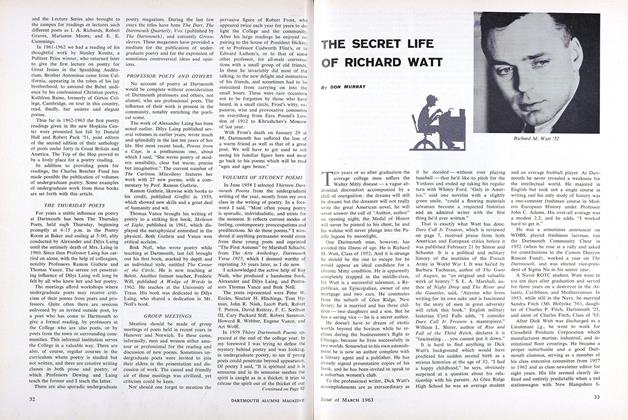

FeatureTHE SECRET LIFE OF RICHARD WATT

March 1963 By DON MURRAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1963 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY -

Article

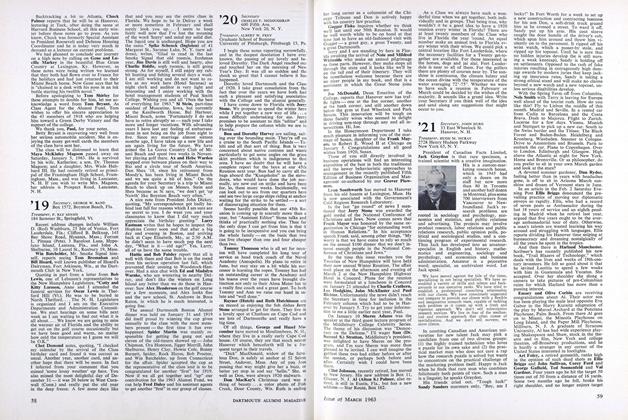

ArticleScholarly Stimulator of Comparative Study

March 1963 By G.O'C. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1963 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY

BENFIELD PRESSEY

-

Books

BooksPETTICOAT FEVER

October 1935 By Benfield Pressey -

Article

ArticleMusic In the Center

February 1940 By Benfield Pressey -

Article

ArticleDavid Lambuth (1879-1948)

October 1948 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Books

BooksTHESE WERE ACTORS.

January 1956 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

FeatureFive Wishes for America

By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Books

BooksSTUDIES IN THE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE DRAMA.

MAY 1959 By BENFIELD PRESSEY

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Books

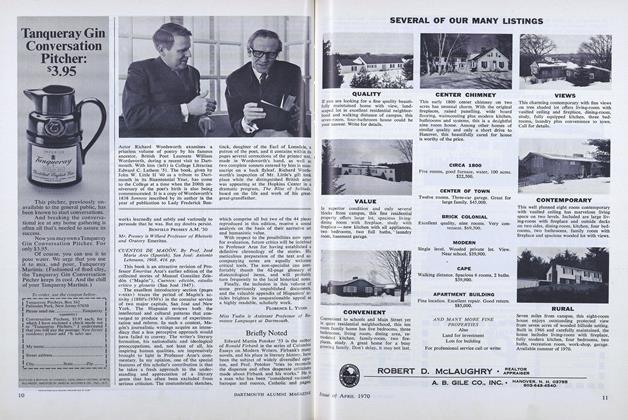

BooksBriefly Noted

APRIL 1970 -

Books

BooksNOTES FROM A BOTTLE FOUND ON THE BEACH AT CARMEL.

APRIL 1964 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksLew Stilwell: A Fine Teacher

JUNE 1963 By JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28 -

Books

BooksSubways Run on Time

May 1975 By MORTON M. KONDRACKE '60 -

Books

BooksLUCY CRAWFORD'S HISTORY OF THE WHITE MOUNTAINS.

DECEMBER 1966 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29