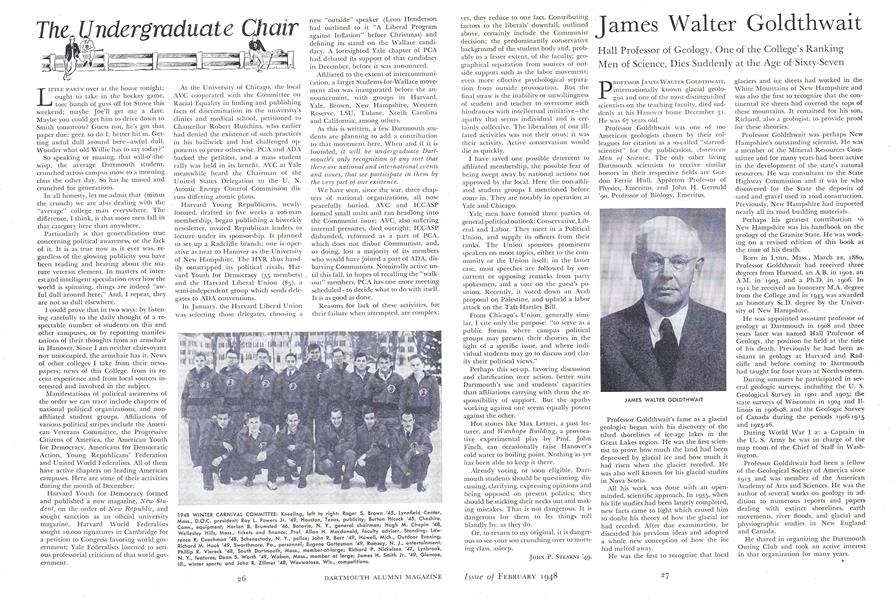

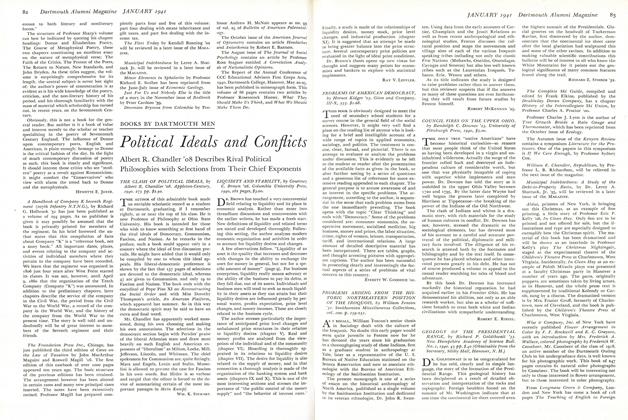

Hall Professor of Geology, One of the College's Ranking Men of Science, Dies Suddenly at the Age of Sixty-Seven

PROFESSOR JAMES WALTER GOLDTHWAIT, internationally known glacial geologist and one of the most distinguished scientists on the teaching faculty, died suddenly at his Hanover home December 31. He was 67 years old.

Professor Goldthwait was one of 100 American geologists chosen by their colleagues for citation as a so-called "starredscientist" for the publication, AmericanMen of Science. The only other living Dartmouth scientists to receive similar honors in their respective fields are Gordon Ferrie Hull, Appleton Professor of Physics, Emeritus, and John H. Gerould '90, Professor of Biology, Emeritus.

Professor Goldthwait's fame as a glacial geologist began with his discovery of the tilted shorelines of ice-age lakes in the Great Lakes region. He was the first scientist to prove how much the land had been depressed by glacial ice and how much it had risen when the glacier receded. He was also well known for his glacial studies in Nova Scotia.

All his work was done with an openminded, scientific approach. In 1935, when his life studies had been largely completed, new facts came to light which caused him to doubt his theory of how the glacial ice had receded. After due examination, he discarded his previous ideas and adopted a whole new conception of how the ice had melted away.

He was the first to recognize that local glaciers and ice sheets had worked in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and was also the first to recognize that the continental ice sheets had covered the tops of these mountains. It remained for his son, Richard, also a geologist, to provide proof for these theories.

Professor Goldthwait was perhaps New Hampshire's outstanding scientist. He was a member of the Mineral Resources Committee and for many years had been active in the development of the state's natural resources. He was consultant to the State Highway Commission and it was he who discovered for the State the deposits of sand and gravel used in road construction. Previously, New Hampshire had imported nearly all its road building materials.

Perhaps his greatest contribution to New Hampshire was his handbook on the geology of the Granite State. He was working on a revised edition of this book at the time of his death.

Born in Lynn, Mass., March 22, 1880, Professor Goldthwait had received three degrees from Harvard, an A.B. in 1902, an A.M. in 1903, and a Ph.D. in 1906. In 1911 he received an honorary M.A. degree from the College and in 1945 was awarded an honorary Sc.D. degree by the University of New Hampshire.

He was appointed assistant professor of geology at Dartmouth in 1908 and three years later was named Hall Professor of Geology, the position he held at the time of his death. Previously he had been assistant in geology at Harvard and Radcliffe and before coming to Dartmouth had taught for four years at Northwestern.

During summers he participated in several geologic surveys, including the U. S. Geological Survey in 1901 and 1905; the state surveys of Wisconsin in 1904 and Illinois in 1906-08, and the Geologic Survey of Canada during the periods 1906-1915 and 1925-26.

During World War I as a Captain in the U. S. Army he was in charge of the map room of the Chief of Staff in Washington.

Professor Goldthwait had been a fellow of the Geological Society of America since 1913 and was member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was the author of several works on geology in addition to numerous reports and papers dealing with extinct shorelines, earth movements, river floods, and glacial and physiographic studies in New England and Canada.

He shared in organizing the Dartmouth Outing Club and took an active interest in that organization for many years.

In 1906 he married Edith D. Richards of Newtonville, Mass., who died last AuSust.

Survivors are a sister, Mrs. Isaiah Bowman of Baltimore, Md.; and two sons, Richard P. Goldthwait '33, professor of geology at Ohio State University, and Lawrence Goldthwait '36, professor of geology at the University of Maine. The funeral was held January 4 in Rollins Chapel.

Professor Goldthwait's death brought forth many tributes to him as a person, a teacher and a scholar. Following are two of these, written on behalf of the Department of Geology, by Prof. E. D. Elston, his colleague for 37 years, and by Prof. Richard E. Stoiber '32, department chairman and a former student of Professor Goldthwait's:

To THOSE OF us who knew Professor Goldthwait intimately and who worked with him, his untimely passing came as a great shock.

He was modest, yet his work and achievements in geology, and particularly in glacial geology, had won for him both national and international recognition. Those of the alumni who had the opportunity of taking a course with him are fortunate in that they not only worked with a man who knew his subject thoroughly, but also one who taught in a very stimulating manner tending to excite the interest of the student to the point of additional study.

He was always anxious to further the progress of the student and took particular pleasure in watching those who went into geological work develop and advance in their chosen field. And while it was not possible for him always to keep in close touch with the numerous men who did follow the profession, his face always showed his keen delight upon learning of their advancement.

A considerable part of his effort at Dartmouth was spent in the elementary course in which large numbers of men enrolled. For many this was their only experience with geology and his treatment of the subject matter was original rather than stereotyped. His emphasis was upon relatively few facts and principles, striving to show relationships and to develop the power of observation and interpretation on the part of the student.

His fields of interest were extremely wide and varied and his intellect so keen that it was a joy to work with him. During times when the department was faced with knotty problems, his sage advice coupled with his rare sense of humor often made the task or problem seem much less difficult.

The writer was associated very closely with him for 27 years and never found a finer man with whom to work. In his death, the Department of Geology and Dartmouth College have suffered a heavy loss, and I have lost a much loved friend and colleague. E. D. ELSTON JAMES WALTER GOLDTHWAIT was a scholar, a stimulating teacher and a good friend. His scholarship was sound, backed by clear thinking and geological observations from which he skillfully wove new parts of the story of the earth in glacial or more recent time. Accompanying his interest in research was a desire to publish his findings in simple accurate language. His scientific work was not bounded by conventional geologic thinking: many of his scholarly conclusions resulted from an original approach to basic problems.

Contrary to the view held by many other geologists, he believed that the New England coast has not changed its elevation in historic time. In this connection few others would have studied Nathaniel Bowditch's chart and sailing directions for Salem Harbor, published in 1806, or had they done so, recognized the opportunity for a scientific contribution afforded by the observation that on very low or high tides in 1805 certain ledges in Marblehead Bay were bare and others just covered. This led Dr. Goldthwait to visit the same spots on October 12, 1935, when there was an extreme tide to see if the ledges would be again exposed. Finding that they were as described in 1805 this evidence was used in the argument that there has been little or no subsidence of the coast in the 130- year interval.

In the course of geologic investigation cinders were discovered below the surface in the peat deposits of Saugus Marsh near the railroad tracks. It was typical of Walter Goldthwait that he followed up the discovery by inquiring as to the date that coal-burning locomotives were first run over the marsh. With this information one could tell how fast the peat was forming. Such examples do not measure the importance of his work but illustrate the breadth and keenness of his inquisitive spirit. Vision together with the desire to consider all the evidence bearing upon geological problems as well as those of more general scope are rare qualities which he possessed to a marked degree.

The character of Walter Goldthwait's scholarship was reflected in his teaching. To hundreds of Dartmouth men he taught a stimulating elementary course which was continually revised to include his own most recent observations and those of other scientists. He aimed not to make geologists of his elementary students but to develop their powers of analysis using geological material. As a student of Dr. Goldthwait's I well remember the final examination in his course in glacial geology which illustrated the flexibility in his teaching and thinking. A week previous to the examination, unknown to the students, a publication had been issued expounding a new idea in glaciology. Dr. Goldthwait recognized the validity of some of the arguments which are today accepted and the errors in other judgments and had seen in this publication a perfect test for the student. The final examination disregarded the formal work of the course and consisted of a request for comment as to the soundness of the ideas in the new publication.

His interest in recent investigations in his own and allied fields and his desire to bring these to the attention of his students was in evidence in his last class in glacial geology in which glacial studies in Scandinavia made during the war, only now available here, were presented and analyzed. This approach to science and the teaching of science has not been without impact on Dartmouth students. Over many years returning alumni in diverse walks of life have paid him warm tribute.

As a friend Walter Goldthwait was loyal and helpful. He was a man of wide interests in subjects as diverse as skiing and New England antiquities. He was a gifted story teller and sparkled with good humor. He is greatly missed.

JAMES WALTER GOLDTHWAIT

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleATOMIC ENERGY CONTROL

February 1948 By CHESTER I. BARNARD, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

February 1948 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

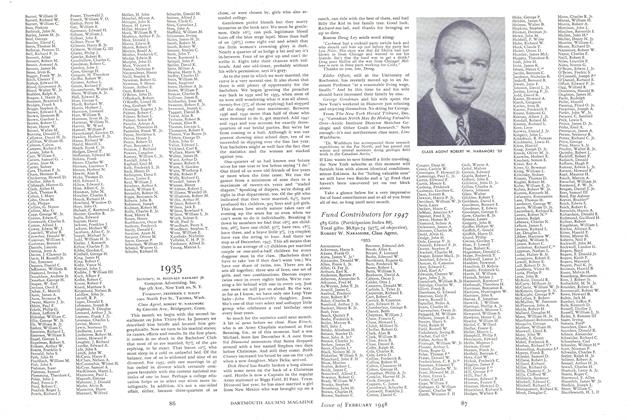

Class Notes1935

February 1948 By H. REGINALD BANKART JR., FREDERICK T. HALEY, ROBERT W. NARAMORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1948 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI, ERNEST H. MOORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

February 1948 By JAMES T. WHITE, RICHARD A. HENRY, DONALD E. COYLE

Richard E. Stoiber '32

Article

-

Article

ArticleROBERT JACKSON '00 PRESENTS MEMORIAL TO FRANCE

JUNE, 1928 -

Article

ArticleSTANFORD COMES EAST

NOVEMBER 1931 -

Article

Article1957 Football Schedule

January 1957 -

Article

ArticleFord Grant of $675,000

JANUARY 1963 -

Article

ArticleWILLIAM JEWETT TUCKER

March, 1915 By Kan-Ichi Asakawa '99 -

Article

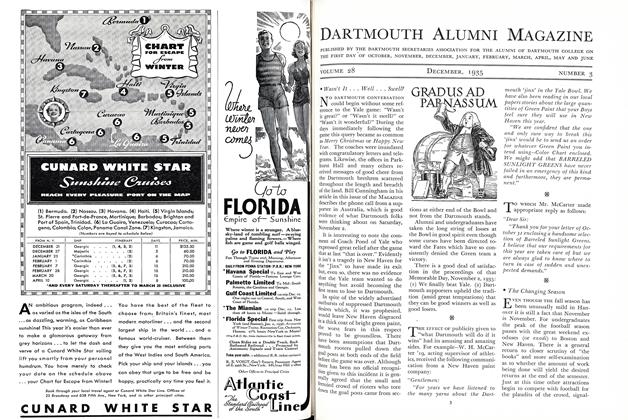

ArticleWasn't It ... Well ... Swell?

December 1935 By The Editor