Frederick Hall Professor of Mineralogy

The ultimate classroom for Richard E. Stoiber, the Frederick Hall Professor of Mineralogy, is the volcanic mountain range which rims the Pacific coast of Central America. There, where the earth still grinds and growls in the glacial process of shifting and change, he leads each fall the 20 to 25 majors in the Earth Sciences Department to learn about some of the mysteries of the earth by direct observation and participation in research.

For the students, who may find themselves climbing alongside a red hot lava flow or trudging day after day at dawn with heavy equipment up the slopes of volcanoes to take heat sightings for thermal profiles of the mountains, the experience is one they never forget. And for Professor Stoiber, who today is recognized as one of nation's more innovative volcanologists, it is an ideal setting in which to bring into meaningful focus the facts and concepts discussed earlier in the classrooms of Silsby Hall.

"It's only part of the process to take students to see for themselves the phenomena they are studying," he says, swiveling with restless energy to point to a contour relief map knobby with the 500 miles of volcanic ranges which stand like a spine along the common backbone linking Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua and which have become his off-campus laboratory for several weeks each year.

"Studying comes alive for students when they can work with faculty members on the sites where we actually are 'doing our thing.' In that way, our students learn not only what we're doing but how to engage in scientific inquiry by helping us do it."

As chairman of the department for the third or fourth time since he joined the Dartmouth faculty as a geologist in 1937, he is always conscious of the departmental overview. Thus, Professor Stoiber stresses that the Central American volcanoes comprise only a fraction of the off-campus laboratories offered earth science majors at Dartmouth. Other trips take the students as far afield as the American southwest or as near as parts of New England - wherever the other seven or eight members of the tightly knit department are conducting research in their respective specialties.

Perhaps it is this readiness of the earth sciences faculty to bring undergraduates, as well as graduate students, into their research that had led to the development of an informal "Dartmouth Mafia" in the field. Professor Stoiber points out, with casual deference only partially obscuring his pride, that there are more than 400 professionals who have entered the earth sciences field with one or more degrees from Dartmouth since he started his teaching career. "We know where all of them are," he said, referring to a departmental map with pins marking the locations "and we write to each of them at least once a year."

It was the same kind of faculty interest in undergraduates that started a young Stoiber thinking about geology as a career when he came to Dartmouth from South Orange, N.J., in 1928. He had chosen Dartmouth over Princeton because the natural setting of the College appealed to his instinct for outdoor life.

That interest was given a practical focus when he took a freshman course with the late Prof. James Walter Goldthwait. But. Professor Stoiber recalls, it was the teaching of Harold Bannerman, geology professor emeritus now living in Middletown, Conn., that convinced him that geology was "not just collecting pebbles" and inspired him to major in geology.

Graduated from Dartmouth in 1932, Professor Stoiber went directly to M.I.T. for graduate study in mining geology. He returned to Dartmouth in 1935 for one year to teach Professor Bannerman's courses while his former mentor was away on sabbatical, and finally he joined the faculty as an instructor in 1937, the year he received a Ph.D. from M.I.T.

His special interest at that time was in mining geology and optical crystallography, and he was writing a paper on zinc deposits in Oklahoma when he heard the neWS of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor His work on crystals had already attracted attention, and Professor Stoiber, by then an assistant professor, was recruited early by the U.S. Army Signal Corps as a civilian specialist to help organize the supply, design, and production of special quartz crystal units needed for the millions of radios which were to provide the communications network for the entire military from tank platoons to Army groups during World War II.

Back at Dartmouth after the war, Professor Stoiber returned to his study of minerals and where they are found and why. In 1960 he decided there was a need for intensive research on the role of volcanic action in creating deposits of various minerals. It had long been recognized that there are metals in the gases flowing out of active volcanoes, but Professor Stoiber suspected more could be learned about that phenomenon and its meaning.

In recent years, Professor Stoiber and his students have gone beyond measurement of metals in the gases of volcanoes, although he is still doing that and working at ways to achieve more accurate data and interpretations. He is also exploring the anatomy of volcanoes and their relationship to earthquakes in several other ways. He and his students, for instance, have already plotted contour maps of heat emanating from volcanic mountains with heat sensing devices on the ground and thus have identified "hot spots" even before lava flows emerge from them. Now, based on his initial work, which has been supported for many years by the National Science Foundation, Skylab astronauts will take heat sensing "images" of volcanoes in the vicinity of Managua, Nicaragua, from their space station hundreds of miles above the earth to see what future insight high altitude instruments may shed on volcanic activity. The information gained by Skylab in its dawn overflights of Nicaragua will be correlated with ground observations by Professor Professor Stoiber and his students when they are there this summer.

He is finding definite relationships of patterns, and it is a mark of the interest generated in his work that he is scheduled to report on it at the massive joint meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the National Council for Science and Technology of Mexico, to be held from June 20 to July 4 in Mexico City on the theme "Science and Man in the Americas."

Although he still considers himself a "johnny-come-lately" in the field of volcanology ("I haven't yet done work in Hawaii and Japan"), his work in pursuit of knowledge about the earth's aging crust has taken him to Italy, Scandinavia, the U.S.S.R., and East Africa, in addition to Central and South America.

As with most teachers, he enjoys his students - both graduate and undergraduate - as much as his research. The Department will have 19 candidates working for advanced degrees next year along with a couple dozen undergraduate majors, and many more taking an Earth Sciences course or two.

In his view, students haven't really changed much over his 36 years of teaching at Dartmouth, except that today he notes a greater concern for choosing careers that will be personally meaningful. Students have the advantage of marvellously sophisticated equipment, he says. But with all that, he still leads his students a merry chase in the mountains.

Just as he enjoys reading in volcanoes clues to the earth's past, he also enjoys his link with Dartmouth's past through the Frederick Hall Professorship in Mineralogy, which he has held since 1971. The academic "chair" was endowed by the 1838 bequest of Mr. Hall, who was graduated from Dartmouth in 1803, served as a professor of chemistry at several institutions, and was for a time president of Mt. Hope College.

R.B.G.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow the Dutch Handle It

June 1973 By Robert D. Haslach '68 -

Feature

FeatureTHE FIRST COED YEAR

June 1973 By Bruce Kimball '73 and Andrew Newman '74 -

Feature

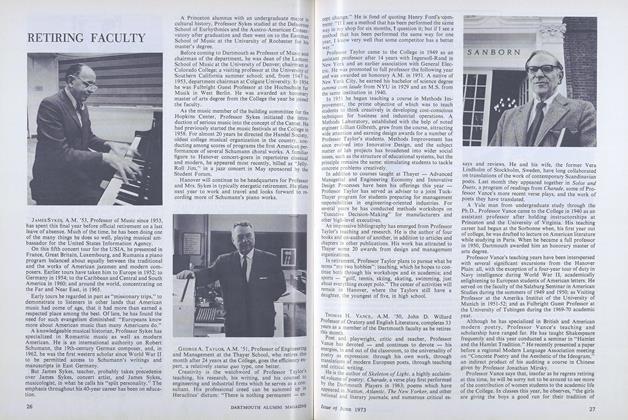

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1973 -

Feature

FeatureClass Officers Weekend

June 1973 -

Feature

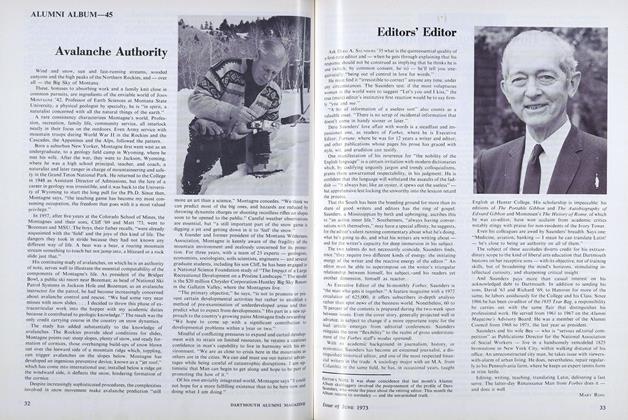

FeatureAvalanche Authority

June 1973 -

Feature

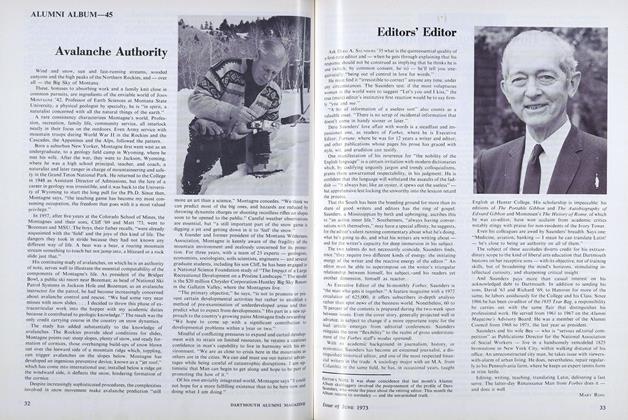

FeatureEditors' Editor

June 1973 By MARY ROSS

RICHARD E. STOIBER '32

-

Books

BooksGEOLOGY OF THE PRESIDENTIAL RANGE

January 1941 By Richard E. Stoiber '32 -

Article

ArticleJames Walter Goldthwait

February 1948 By Richard E. Stoiber '32 -

Books

BooksINTERNAL STRUCTURE OF GRANITIC PEGMATITES.

December 1949 By Richard E. Stoiber '32 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

SEPT. 1977 By Richard E. Stoiber '32

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE COURSE IN SEVEN SEMESTERS

March 1912 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH COLLEGE

MAY, 1928 -

Article

ArticleDetroit Pow-Wow

March 1950 -

Article

ArticleThe Nano Brewer

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Juliette Rossant ’81 -

Article

ArticleSANBORN ENGLISH HOUSE

April 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1936 By William B. Rotch ’37