In which Amherst squirrels and Dartmouth dogsvie for numerical honors, and an allergicapplicant for '57 gets a free and bewilderingcorrespondence course in the liberal arts

Asa journal devoted to letting Dart mouth men know what goes on in Hanover, we hate to admit this, but it was not until we had read the October issue of the Amherst Alumni News that we knew anything at all about an epistolary imbroglio involving Amherst, Dartmouth, their respective directors of admissions, an unaccommodated applicant for college, dogs, squirrels, acorns and hundreds and hundreds of words.

Knowing that the mere mention of Hanover dogs will immediately arouse the most intense sort of interest on the part of Dartmouth men, we hasten to fill in what Albert I. Dickerson '30, Dartmouth's erudite director of admissions, would call a lacuna in our coverage of College affairs.

The whole business began when Dean Eugene S. Wilson of Amherst received a most unusual inquiry from a young applicant in tile East:

Dear Sir:

I should like to enter Amherst College, Fall, '53. On that hope I am writing for a catalogue. However, a condition may preclude my application. I am allergic to dogs, their antics, and their barking. Their actual presence itself does not disturb me not the dogs themselves - only their activities.

Should Amherst, the community, be hospitable to dogs, then Amherst College would not be for me. A university in a large city would afford me a desirable condition on the dog problem. But should your judgment conclude that I might be comfortable at Amherst, just ignore my request for a catalogue.

Yours sincerely, William B. Rogers.

Having on previous occasions had his leg pulled by his Dartmouth counterpart, Dean Wilson for a number of reasons suspected a repeat performance and replied as follows:

My dear Mr. Rogers: Amherst is a small community and, like all small country communities, very fond of dogs. The town is full of them they even invade the dormitories and classrooms. They are, for the most part, well-mannered dogs and dogs of unusual breeding. But this does not interest you, a person who is allergic to them.

In the heart of our campus is an oak grove, and these oaks bear many acorns. All year long squirrels engage themselves in burying these acorns. Many of the dogs in the town know about these squirrels and spend hours stalking them from one corner or another. That is why we have so many dogs on the Amherst campus.

Have you thought of Dartmouth College, a very fine institution north of Amherst? So far north, it is too cold for dogs. I suggest you investigate this institution as well as city institutions.

You may have heard some rumors about there being a good many old dogs in Hanover, but on scientific exploration we found, through our Smith College agents, that these old dogs are wolves of the two-legged variety. Though they are playful, they are not dangerous. In our state there is an open season on them at all times with no bag limit. They are such easy hunting that few people bother to chase them any more. As our local haberdasher said last week: "I took three of them for plenty a week ago Saturday, but it was so easy that I hesitated to speak about it." If you do write Dartmouth, address your letter to Mr. A. I. Dickerson, their director of admission. He will be sympathetic with your allergy problem because he is allergic to many things, but dogs is not one of them.

Sincerely, Eugene S. Wilson, Director of Admission

The story next takes on a certain piquancy with the development that Mr. Dickerson was innocent, this time, and that Mr. Rogers apparently was no figment of the imagination. The young gentleman was quickly heard from again:

Dear Dr. Wilson: I take my pen in hand to indite to you a reply to your reply to an inquiry of mine as to the state of the dog cult upon the Amherst campus.

The job is not an easy one for a single reason: I can't quite make you out as you reveal yourself in your epistle on this item of social interest.

Are you a philosophical character a psychological structure concerned with getting something said which will not let itself be put in phraseology understandable to the commonalty to such who have not a college degree, but are determined to acquire one, hoping in the process to gain what is the crux of the matter, some information, some inspiration, of course, some amusement?

Should I make up my mind to matriculate at Amherst College, ill spite of the dogs, vying wjth the squirrels in burying acorns in one corner or the other of the campus —and be accepted (more of the condition) I would closely study you.

Of Dartmouth I have never heard. On second thought, a guy from this place is said to be playing football at a school bearing that name, a few steps nearer the Pole than Amherst. But, never having heard of the Dartmouth joint, before this "personal" showed up in the public prints, I choose to persist in my lifelong conditioning, negatively, to the effect that there is no such place as Dartmouth!

That Smith College? I know ten thousand Smiths, but that there is a Smith College I say, quit your kidding. However, giving to the idea a thorough going over, I am willing to take your statement at face value and consider this Smith school an institution where some FBI'S are trained you write darkly of "your Smith College agents."

But truly, your paragraph about the dogs of Dartmouth that are actually wolves, but playful wolves, the sort of animal that in your state may be bagged by the gunful quite legally, and open-mindedly, haberdashers doing so without guns, has me topsyturvy.

Really, what I gather from the brambles of your letter is, I am not wanted at Amherst College. That's that. Very well. So!

But why did you not do as I suggested that, in case you were not the place for me, you would ignore my letter about my coming?

And why suggest I write to this fellow A. I. Dickerson evidently a dog worshipper -about Dartmouth? Oh, why!

Oh, why! Let me tell you to be nasty. Dog worshippers hate non-dog worshippers! With an In Faith, Hope and Charity,

Yours sincerely, William B. Rogers.

Enclosed with this letter was a communication from another eastern college advising him, in all frankness, that "it would not be wise for me to encourage you to matriculate here," and wishing him every success in "the planning of your future education."

Mr. Dickerson, apprised of what was afoot at Amherst and of the suspicion that had been directed his way, now enters the epistolary lists. As- a warm-up he wrote Dean Wilson's secretary a letter which we quote in part:

Yours of the 19th inst. opened: "Mr. Wilson has gone out of town again." I hope you will make a note of that for his epitaph.

By the way, while you are working on Mr. Wilson's epitaph, you might make a note of Mr. Rogers' concluding words: "Just ignore my request for a catalogue." It strikes me that when Mr. Wilson is firmly planted under Amherst's sod, Mr. Rogers might well have contributed the headline for the Wilson gravestone. ....

Sincerely,

P.S. As I am leaving on a trip to Cleveland before this letter is transcribed, I am asking my secretary to sign and send it in my absence.

"On the same day," states the AmherstAlumni News, "Dean Wilson determined the truth of Mr. Rogers' existence. 'As he was leaving town on a short trip,' he asked his secretary to forward the evidence to Mr. Dickerson 'and to say he guesses there is really a guy who hates dogs.' He added his apologies for suspecting his Hanover colleague."

The prolix Mr. Dickerson, now thoroughly warmed up, spurred his dictating machine into a gallop, lowered his lance, and showed that he was just as scintillatingly adroit as he was in the days when he wrote "The Gilded Shovel" for The Dartmouth and the 1930 class notes for this magazine. By means of a carbon copy Dean Wilson was spared any lacuna in his knowledge of what Mr. Dickerson wrote to Mr. Rogers:

Dear Mr. Rogers:

Mr. Eugene Wilson, who is a very considerate person and, incidentally, one of rare charm, has thoughtfully sent to me his correspondence with you, so that X might have this background when I heard from you. Modest as Mr. Wilson is by instinct, I can see how he might have taken it for granted that you would be influenced by his eloquent representation on behalf of Dartmouth. Also, he knows how much I value every opportunity to enjoy the orotund, if sometimes obfuscated, quality of his prose.

Although it now appears clear that you could hardly be interested in either Amherst or Dartmouth as a college for yourself, I hope you will pardon me for thus thrusting myself gratuitously into this correspondence, in order to fill certain lacunae in it with regard to Amherst, Dartmouth, Smith, dogs, squirrels, and Mr. Wilson.

Perhaps we should take Dartmouth first, to clear away an air of unreality which seems to pervade this correspondence. Indeed, I am often troubled by the skepticism of this age. You question the very existence of Dartmouth College, one of America's most ancient institutions of higher learning, and one which is widely believed to be the liveliest intellectual center north of Chicopee; and you also throw into question the reality of Smith College, a seminary for young ladies which was founded by the Smith Brothers' sister, Sophia (who was one of the most famous beardless ladies of her time), and which is palpably and tremulously real. And I seem to detect, even in Mr. Wilson, himself, a certain skepticism about the essential reality of a Mr. William Rogers, who is allergic to the antics of dogs. This is surprising, because Mr. Wilson is widely respected by his many friends and admirers as a person of deep faith and understanding in matters of the spirit. However, Mr. Wilson's one weakness, if it may be called that, is a certain prankish penchant, which sometimes causes him to create elaborate fictional situations for the bewilderment of his more innocentminded friends. This harmless and, indeed, somewhat charming human quality of mendacity in Mr. Wilson quite naturally leads him into the error of discovering the same quality in others who are, in fact, quite innocent of guile. (I might add, parenthetically, that the only justification for the title of Doctor, with which you salute him, is an honorary M.D. bestowed upon him in recognition of his prowess in the field of mendacity in early middle age (circa 1897). As it turned out, this was before he reached the fullness of his powers. Mr. Wilson is a late bloomer.)

I wish that I could conscientiously persuade your interest in Dartmouth. Your letters seem to reflect some unusual potentialities not only a pith of phrase, but a rare power of apperception. Take, for example, your comment to Mr. Wilson: "Really, what I gather from the brambles of your letter ..." there you illuminate in a flash one of the most fascinating paradoxes in the Wilson character, a certain piquant prickly quality in his personality. As with certain personalities on a more heroic scale, it may be difficult sometimes "to see the forest for the trees," so with Dr. Wilson, one may, on first encounter have difficulty in seeing the thicket for the thorns. But, believe me, Mr. Rogers, there is real warmth and true goodness behind that mettlesome facade.

However, I guess we will just have to face it: unless you can sublimate your allergy to the antics of dogs, Dartmouth is not for you. Actually, with his customary modesty and generosity in discussing Amherst in relation to other colleges, I am afraid that Dr. Wilson overstated both the canine abundance of Amherst and the dog-poverty of Dartmouth. Indeed, a theory is widely held among authoritative biologists and archaeologists that there was a distinct migration of Canis Familiaris in the late Pleistocene northward from the miasmal meadows and swamps of the middle Connecticut River Valley to the hill country of this area where, all climatologists agree, the legendary dry cold provides a more beneficent environment for both man and beast. At any rate, dogs are a prominent feature of the domestic, social, and educational environment here; and it is only fair to you to recognize very frankly that the domestic canine strain is rather an antic one. This is true both in the general and in the particular. Symbolic of the environment is the fact that a large Labrador retriever accompanies the president of the College everywhere he goes. This dog, known as Rusty, originally had an antic spirit at least average for his environment, but he has quieted down somewhat of late. It is locally believed that this may be due to Rusty's habit of spending his office hours quietly masticating and digesting correspondence retrieved from the president's waste basket, which would have a sobering effect on anyone. Prior to Rusty, another canine symbol of great prominence and of uncertain origin was the most popular campus figure of his time. His activities and achievements were copiously covered in the daily press. He attended all athletic contests, baying in victory and howling in defeat. (He is chiefly remembered as a howler.) He gave nightly serenades in the center of the campus to the accompaniment of the College chimes, concerning which he had strong feelings. His most characteristic addiction was to empty beer cans, with which he was plentifully supplied by visiting Amherst students. Indeed, one theory advanced at the time of his mysterious disappearance although it must be said that there is no real evidence in support of it was that he wandered off down the valley (in spite of the climatic and other advantages of this area) in quest of an even more abundant supply of beer cans, closer to the source. He had real elan with a beer can.

And so it goes. Dogs here go to class, to the library, to the movies, to the dining halls, and to church. On the playing fields, they usually outnumber the biped population by approximately two and one-half times, per square foot. The squirrel population is far, far behind. Out of courtesy to Mr. Wilson, I think I will drop the squirrel question right here. He is understandably somewhat confused about the ecological relationships of oaks, acorns, dogs, and squirrels: bionomics is not really Mr. Wilson's field.

Although your particular requirements, Mr, Rogers, seem to rule out Dartmouth for you, I do not feel that you should lightly dismiss the opportunities at Amherst, which are extraordinary in many respects. I happen to have an Amherst catalogue at hand and I am sending it to you. (I got this catalogue for my daughters because there is more information about Smith and Mount Holyoke in it than is available in their own publications.) You, yourself, have already recognized the instructive possibilities of studying Dr. Wilson. Amherst has many other advantages. It has a nice little library and unquestionably the best gymnasium in the whole Amherst, Smith, Mount Holyoke community, where books, musicians, psychiatrists, and . shower rooms are so generously shared. In addition, there is a certain charm about the Amherst campus.- Smith girls, for example, think that it is cute. I beg you, therefore, Mr. Rogers, not to summarily dismiss Amherst from your consideration simply because Mr.(I mean Dr.) Wilson quite pardonably let himself get just a little boastful about Amherst's dogs, squirrels, and acorns. If I can be of any further help to you with regard to your educational plans, please do not hesitate to get in touch with me.

Sincerely, Albert I. Dickerson

Except for a few newspaper clippings about squirrels thoughtfully forwarded to Dean Wilson by Mr. Dickerson, l'affaire Rogers became a closed matter. "Where Mr. Rogers matriculated is unknown," concludes the Amherst magazine. "Certain it is, however, that he has been exposed to a liberal education." And exposed also, we would add, to the fact that directors of admissions are human enough to be frolicsome -even squirrelish - now and then.

PHOTOGRAPHIC FOOTNOTE: An ideal illustration for this feature would be a picture of Albert I. Dickerson '30 with a Hanover dog. There is no such picture in the file and we are unable to take a new one. Mr. Dickerson is out of town.

THE LATE, LAMENTED GERANIUM, who was very fond of perching on the Senior Fence.

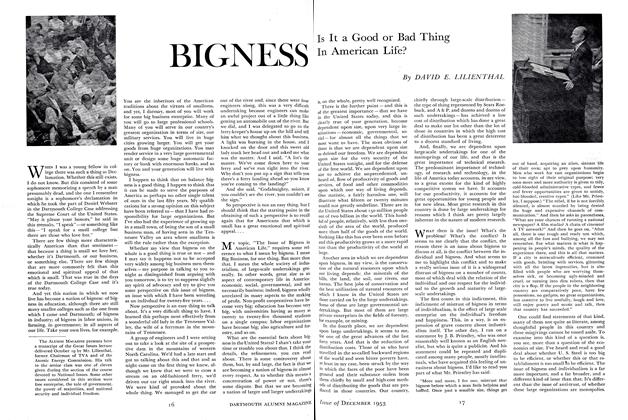

REINFORCEMENTS COMING ALONG: A bright Dartmouth future on the campus and playing fields and in the college buildings is predicted for these two pups basking in the autumn sunshine.

GREASY GLEASON '54, whose Dartmouth days end in June, ready to make a great issue out of his bone, possibly that of a giant Hanover squirrel.

THE KNOWING LOOK that comes from graduate study is displayed by Kip Elberty, part of the multitudinous canine population at Wigwam Circle.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleBIGNESS

December 1953 By DAVID E. LILIENTHAL -

Article

ArticleCharles Ransom Miller '72

December 1953 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, w. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1953 By HENRY R. BANKART, JOHN WALLACE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

December 1953 By Lambert & Feasley, Inc., PETER B. EVANS, CHARLES S. MCALLISTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1953 By SIMOND J. MORAND III, LT. SCOTT C. OLIN

Article

-

Article

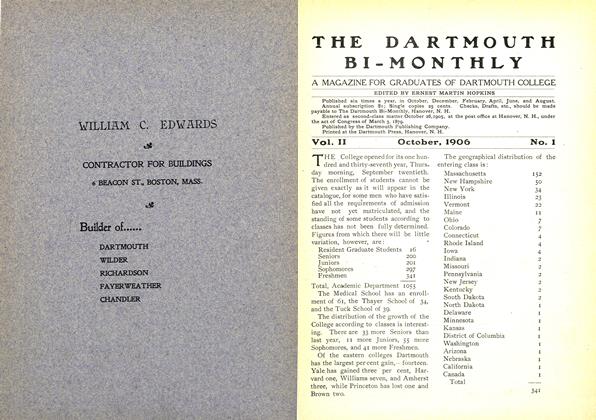

ArticleTHE College opened for its one hundred and thirty-seventh year,

OCTOBER, 1906 -

Article

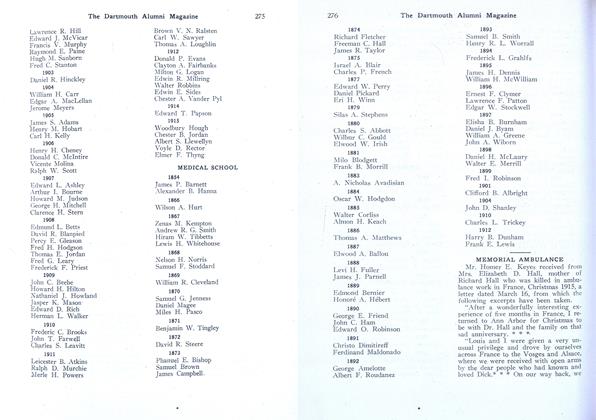

ArticleMEMORIAL AMBULANCE

April 1917 -

Article

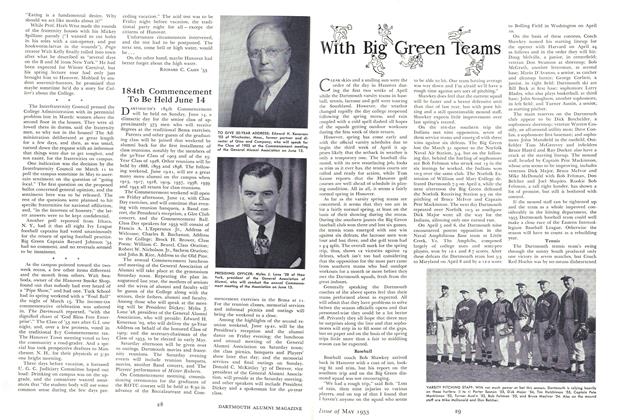

Article184th Commencement To Be Held June 14

May 1953 -

Article

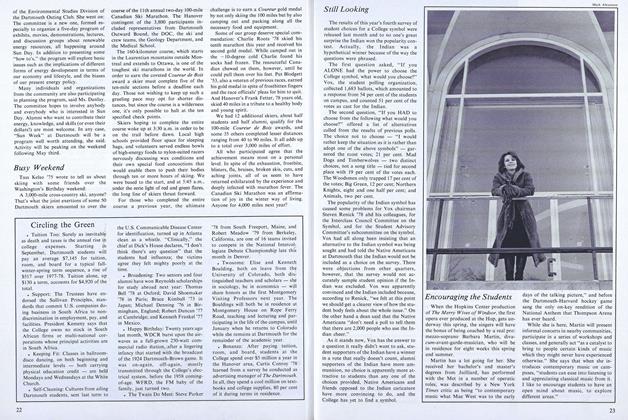

ArticleStill Looking

APRIL 1978 -

Article

ArticleJust One Question

MARCH 1999 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1971 By STEPHEN K. ZRIKE '71