Is It a Good or Bad Thing In American Life?

WHEN I was a young fellow in college there was such a thing as Declamation. Whether this still exists, I do not know. But this consisted of some sophomore memorizing a speech by a man presumably dead, and the one I remember tonight is a sophomore's declamation in which he took the part of Daniel Webster in the Dartmouth College Case addressing the Supreme Court of the United States. "May it please your honors," he said in this tremulo, "I speak" —or something like this —"I speak for a small college but there are those who love her."

There are few things more characteristically American than that sentiment that because a thing is small we love her, whether it's Dartmouth, or our business, or something else. There are few things that are more commonly felt than this emotional and spiritual appeal of that which is small. That was true in the days of the Dartmouth College Case and it's true today.

And yet this nation in which we now live has become a nation of bigness: of bigness in education, although there are still many smaller colleges such as the one from which I came and Dartmouth; of bigness in industry; of bigness in labor unions, in farming, in government; in all aspects of our life. Take your own lives, for example.

You are the inheritors of the American traditions about the virtues of smallness, and yet, I daresay, most of you will work for some big business enterprise. Many of you will go to large professional schools. Many of you will serve in our country's greatest organization in terms of size, our military services. You will live in huge cities growing larger. You will get your goods from huge organizations. You may render service in a very large governmental unit or design some huge automatic factory or bank with enormous banks, and so on. You and your generation will live with bigness.

I happen to think that on balance bigness is a good thing. I happen to think that it can be made to serve the purposes of America as perhaps no other single talent of ours in the last fifty years. My qualifications for a strong opinion on this subject have been referred to that I have had responsibility for large organizations. But I've also had the experience of growing up in a small town, of being the son of a small business man, of having seen in the Tennessee Valley an area where smallness is still the rule rather than the exception.

Whether my view that bigness on the whole is a good thing is true or not and I may say it happens not to be accepted very widely among big business men themselves my purpose in talking to you tonight as distinguished from arguing with you tomorrow, is to try to suppress slightly my spirit of advocacy and try to give you some perspective on this issue of bigness, an issue with which I have been wrestling as an indivdual for twenty-five years. .. .

Now perspective is an easy thing to talk about. It's a very difficult thing to have. I learned this perhaps most effectively from a wonderful old lady in the Tennessee Valley, the wife of a ferryman in the mountains of Tennessee.

A group of engineers and I were setting out to take a look at the site of a prospective dam in the mountains of western North Carolina. We'd had a late start and got to talking about this and that and as night came on the first thing we knew, although we knew that we were to cross a stream on an old-fashioned ferry, we'd driven our car right smack into the river. We were kind of provoked about the whole thing. We managed to get the car out of the river and, since there were four engineers along, this was a very difficult undertaking because engineers can make an awful project out of a little thing like getting an automobile out of the river. But we did, and I was delegated to go to the ferry-keeper's house up on the hill and tell him what we thought about this business. A light was burning in the house, and I knocked on the door and this sweet old lady stuck her head out and asked me what was the matter. And I said, "A lot's the matter. We've come down here to your ferry and we've run right into the river. Why don't you put up a sign that tells you there's a ferry landing ahead so you know you're coming to the landing?"

And she said, "Godalmighty, mister, if you couldn't see the river, you couldn't see the sign."

So perspective is not an easy thing, but I should think that the starting point in the obtaining of such a perspective is to recall again that for Americans that which is small has a great emotional and spiritual appeal. . . .

MY topic, "The Issue of Bigness in American Life," requires some reference to what I mean by bigness. I mean Big Business, for one thing. But more than that, I mean the whole society of industrialism, of large-scale undertakings generally. In other words, great size as an aspect of contemporary life in America: economic, social, governmental, and not necessarily business; indeed, bigness wholly unrelated in many aspects to the making of profit. Non-profit cooperatives have become very big; education has become very big, with universities having as many as twenty to twenty-five thousand students on a single campus; labor organizations have become big; also agriculture and forestry, and so on.

What are the essential facts about bigness in the United States? I shan't take your time or trouble you about that. I think the details, the refinements, you can read about. There is some controversy about them, but, by and large, the fact is that we are becoming a nation of bigness in almost every respect. As to whether this means a concentration of power or not, there s some dispute. But that we are becoming a nation of larger and larger undertakings is, on the whole, pretty well recognized.

There is the further point and this is of the greatest importance that we have in the United States today, and this is clearly true of your generation, become dependent upon size, upon very large in- stitutions economic, governmental, so-cial-for almost all the things that we most want to have. The most obvious of these is that we are dependent upon size to defend our freedom. We are dependent upon size for the very security of the United States tonight, and for the defense of the free world. We are dependent upon size to achieve the unprecedented, un- heard of, flow of productivity of goods and services, of food and other commodities upon which our way of living depends. One statistic, a fairly harmless one, will illustrate what fifteen or twenty minutes would not greatly underline. There are in the United States about 150 million people out of two billion in the world. This hand- ful of people, relatively, with less than one- sixth of the area of the world, produced more than half of the goods of the world. Nothing like this has ever been seen before and this productivity grows at a more rapid rate than the productivity of the world at large.

Another area in which we are dependent upon bigness, in my view, is the conservation of the natural resources upon which our living depends:, the minerals of the hills, the land, the soil, our rivers, our forests. The best jobs of conservation and the best utilization of natural resources of which I know in the United States are those carried on by the large undertakings. Some of these are large governmental undertakings. But most of them are large private enterprises in the fields of forestry, for example, or mining.

In the fourth place, we are dependent upon large undertakings, it seems to me, for one of the great advances of the last forty years. And that is the reduction of distribution costs. Those of us who have travelled in the so-called backward regions of the world and seen bitter poverty have, at least in my case, been struck by the way in which the faces of the poor have been ground and their substance stolen from them chiefly by small and high-cost methods of distributing the goods that are produced in those countries. Our country, chiefly through large-scale distribution the type of thing represented by Sears Roebuck, and A & P, and dozens and dozens of such undertakings has achieved a low cost of distribution which has done a great deal to make our lot other than the lot of those in countries in which the high cost of distribution has been a great deterrent to a decent standard of living.

And, finally, we are dependent upon large-scale undertakings for one of the mainsprings of our life, and that is the great importance of technical research. The predominant importance of technology, of research and technology, in the life of America today accounts, in my view, to a great extent for the kind of highly competitive system we have. It accounts for our productivity, it accounts for the great opportunities for young people and for new ideas. Most great research in this country is done by large undertakings for reasons which I think are pretty largely inherent in the nature of modern research.

WHAT then is the issue? What's the problem? What's the conflict? It seems to me clearly that the conflict, the reason there is an issue about bigness to discuss at all, is the conflict between the individual and bigness. And what seems to me to highlight this conflict and to make a really serious issue of it is a widespread distrust of bigness on a number of counts, most of which deal with the relation of the individual and our respect for the individual to the growth and maturity of largescale undertakings.

The first count in this indictment, this indictment of mistrust of bigness in terms of individualism, is the effect of large scale enterprise on the individual's freedom and happiness. This, in a way, is an expression of grave concern about industrialism itself. The other day, I ran on a statement by J. B. Priestley, who was once reasonably well known as an English novelist, but who is quite a publicist. And his statement could be repeated and duplicated among many people, mostly intellectuals, who have acquired this feeling of uneasiness about bigness. I'd like to read you part of what Mr. Priestley has said:

"More and more, I for one, mistrust that bigness before which a man feels helpless and baffled. Once past a sensible size, things get out of hand, acquiring an alien, sinister life of their own; apt to prey upon humanity. Men who work for vast organizations begin to lose sight of their original purpose; very soon more and more authority is given to tidy, cold-blooded administrative types, and fewer and fewer opportunities are given to untidy, hot-blooded, creative types." (Like Mr. Priestley, I suppose.) "The rebel, if he is not forcibly silenced, is almost muzzled by being denied the huge and expensive channels of communication." And then he asks in parentheses, "What are your chances of running a national newspaper? A film studio? A chain of cinemas? A TV network?" And then he goes on, "After all, there is one rough and ready test which, among all the fuss and bullying, we may not remember. For what matters is what is happening in people's minds, the quality of the experience there, and this is all that matters. If a city is miraculously efficient, crammed with goods, bristling with services, glittering with all the latest ingenuities, but is also filled with people who are worrying themselves sick, or becoming ugly-minded and cruel, or turning into dim robots, then that city is a flop. If the people in the neighboring country are comparatively poor, have few possessions, no gadgets, no great organizations, but contrive to live zestfully, laugh and love, still enjoy poetry and music and talk, then that country has succeeded."

One could find statements of that kind, many of them not quite as literate, among thoughtful people in this country and these misgivings cannot be tossed aside. To examine into this kind of a question is, you see, more than a question of the economics of size. I've heard and read a good deal about whether U. S. Steel is too big to be efficient, or whether this or that establishment is too small To be efficient. The issue of bigness and individualism is a far more important, and a far broader, and a different kind of issue than that. It's different than the issue of anti-trust, of whether these large organizations are monopolies. This kind of an issue forces one and this is why I am glad to have an opportunity to talk to a group of college seniors about it —to examine into the kind of a life that we want, and how to try to attain it. And this is your biggest job. In other words, the values to use fancy talk the intangible values that we set for ourselves. That's what really is at issue in this matter of bigness.

Now the baleful effect of bigness upon individuals applies not only, of course, to business and to cities, which is implied in what Priestley said, but it applies to government, where I've seen it at work. It applies to large labor unions. It applies to almost all the aspects of bigness.

Count Two against bigness is one that's familiar to you. This count is heard principally from small or medium-sized business men, but also from lawyers and government administrators. It is simply this, that bigness in business means monopoly that size, in itself, eliminates competition. This is another expression of the historic fear in this country, a very wholesome fear that we would do well to recall: the fear of concentrated power, the fear of people throwing their weight about.

Count Three in this indictment of bigness is this: a fairly widespread feeling as I think you will observe before very many months go by, if I may be permitted an oblique and almost partisan remark a fear that men who are the product of big business or of bigness generally are not to be trusted with governing us; that such men become dehumanized; that the products of big business in terms of men are men who have become so absorbed in the institutions they have built and operate that they are not good governors. Here we find a strange conflict and one that you will live with the rest of your lives, I daresay: the conflict between needing the fruits of bigness for our very preservation, and for the things we want as a people, and yet distrusting it to such an extent that we frequently set out to destroy it.

Let me give you an illustration of what this means in concrete terms. When the civilian Atomic Energy Commission, of which I was a member, was first organized and brought into being in 1947, most of America's military force had been demobilized. We commissioners had assumed, and so had most of the top military and certainly the country, that this was all right because we had at hand a large stockpile of atomic weapons that could be used in case of an emergency. We went out to the secret storage areas in the far west to look for ourselves and were profoundly shocked to find that this formidable stockpile of weapons simply did not exist. We hardly had a manageable atomic weapon. And so it was necessary, as quickly as possible, to reactivate this enterprise and correct this deficiency. We found, furthermore, that atomic weapons were being made by handicraft methods. You had really to be a Ph.D. in physics to work in the atomic energy weapon fabricating business. This was obviously wrong. We needed quickly to find some way to factory-produce these weapons. We needed a team, an industrial team that had competence in the field of research, research of the kind carried on in universities; that was competent in industrial techniques of mass production, and competent in the field of operations of very difficult systems.

There wasn't time to create such a machine but fortunately such a team existed. That was the A.T.&T. - American Telephone and Telegraph system. Through the Bell Laboratories, which is the research arm of that nationwide telephone system, and the Western Electric, which is its manufacturing arm, and the A.T.&T., its op. erating arm, here ready-made was a team competent to mass-produce atomic weapons. I went to the president of the A.T.&T. and asked on behalf of the AEC and the President of the United States if they would undertake this job. He said if the national security required it, they would, of course, but he'd like to call something to my attention and the attention of the government. We'd asked this organization to undertake this difficult job because it took these three components of research, manufacturing and operation to do this job for the national defense. Two or three months before, Mr. Wilson pointed out, the Department of Justice of the same government had filed suit against the A.T.&T. charging that it was too big and asking that Western Electric and the Bell Laboratories be severed from the system, on the ground that it was against the public interest. Here is one of many, many illustrations of this need for bigness in certain form, of very great bigness, and our mistrust of it to the extent that we would destroy the very thing we need.

I would like especially to pinpoint one major premise: and that is what bigness can do not simply for productivity but for individualism. Because I think this issue will stand or fall on what bigness does against or in favor of the spirit of individualism.

I, at least, would like to assume, and ask you to assume with me for a moment, that bigness, by and large, equals productivity: that we cannot have even our small enterprises in the U. S. without bigness. But, in terms of individualism, we are told that productivity is virtually irrelevant; that productivity of goods is materialism, close quote. Now, if productivity consists of slum clearance such as is going on in such a terrific way in New York City, this is considered something that is for individualism, this is called a social measure. If bigness produces good health service and great hospitals, this is discounted, and not related to productivity. To me the whole argument about materialism as being the sum total of productivity makes very little sense.

I heard a great deal of this in the Tennessee Valley when I first went there with the TVA. We were told that there was no point in providing a great deal of electricity and encouraging farmers into better agricultural practices or doing something about preventing floods, because, after all, these farmers wouldn't be any happier; their wives are just as happy when they have to walk a half a mile for a pail water as they are if they could simply turn a switch. Most of the people who spoke 0f what we proposed to do as materialism were people who lived in cities and never knew any of these discomforts.

Now it's true that while opulence an prosperity do not necessarily make good people, utter poverty, if any of you have ever seen it, is certainly a spiritually degrading thing....

Further, on the opposite side of the virtues of smallness, I should like at least to call your attention to the issue of fear of concentrated power. The fear of concentrated power is almost as old as the Republic. It is based today, in my opinion, largely upon past abuses. Those abuses were real and I have certainly no inclination to minimize them; but what the present fear of concentrated power fails to recognize, it seems to me, is what Frederick Lewis Allen wrote about in his book The Big Change, which I hope most of you have read. This is the story of what has happened to us in the U. S. in the past fifty years; and more particularly, I call attention to the reorganization of society in terms of the control of abuses of economic power, and other kinds of power, that has taken place since 1933. What happened in the early years of the Franklin Roosevelt Administration is called the New Deal, an enterprise in which I had a part; and, I might say, as the days go by I feel prouder of that part all the time. In any case, what occurred at that time was a reorganization of American society in such a way that we have developed techniques and methods of controlling these abuses which give rise to a fear of concentrated power, which, in turn, gives rise to antagonism to bigness, and particularly to big business. Those of us who lived at that time and who helped to bring about this change should feel, I think, that what we did was not without its consequences. To a considerable extent, governmental control or control by private individuals an awareness of the dangers of concentrated power and a growing enlightenment on the part of the managers of large enterprises has been on the whole successful. Today we may relegate the fear of concentrated power to a secondary position.

It seems to me that the essential issue, then, is not how to return to smallness. There are some people I would be very much surprised to find this true of an audience of college seniors but there are many people today, people with considerable influence, some very vocal people, people for whom I have a great deal of respect, who feel that the issue is how to return to smaller units, much smaller units. I suggest that our problem is not that, but how to adapt bigness, this great talent of bigness that we have, to our most deeply felt creed the creed of individualism. Our problem is not to go back to small units all along the line but, having achieved size, no mean task, to make it do the job for our people and for the great purposes of this country. Now this implies in part control, but that's not really the important part. Control, whether governmental or otherwise, is a negative thing; it is not a positive thing. The control of bigness I think we know how to manage. What we need is something that goes way beyond control and that is a means - a positive means, an affirmative means - of making bigness serve the purposes that all of us hold dear. How to sustain our values, our freedom, our concern for the individual under a system of big-scale undertakings.

There are some indications already of what kind of adaptation of bigness is feasible in order to secure the benefits of bigness and minimize the dangers to those things about the individual that are so important to us. This is one of the great tasks ahead. It is partly a task of business management and the word "decentralization" in business is as good as any to describe it. A good deal is being done in this direction. Many enterprises must be, it seems to me, on a national basis; they must be very large to secure economies, to secure research, the best utilization of natural resources, and these other benefits to which I have referred. But they need not all be run from a central headquarters. If they are run this way then there will be an atrophying of the individual; then there will be remote control; then there will be a breaking apart of some of the finest possibilities of bigness; most of all there will be a static society instead of the highly competitive society we have.

This decentralization of business functions is pretty largely a matter of turning over to people in the factories, in the stores, in the communities, in the states, things that, for the most part, twenty-five or thirty years ago, would have been decided in the central headquarters. This same principle needs to be applied to government. I've had some experience in this connection in the TV A.

The Tennessee Valley Authority is known for a number of things, for good or evil depending on one's point of view, but one thing it has done and that is to provide a demonstration - a living demonstration that the functions of the great federal government can be decentralized on a regional and a local basis. One of the most interesting things in the whole TVA story is the way in which functions which are federal and operated from Washington in most parts of the country were, by what I believe to be a wise act of Congress, actually carried out not by federal officials but by contracts between the TVA and a great variety of local or state agencies. This is decentralization of the federal government....

Another favorable development, in terms of the adaptation of bigness to the needs of a people believing firmly in the virtues of individualism, is the change in the kind and standards of the managers of big enterprises. This change in the kind of men who run large organizations is a marked thing, an obvious thing. Part of this is due to the fact that many large enterprises now are dominated by technical issues quasi-scientific issues requiring men of a quite different kind from the socalled "buccaneers," or even the men who came up the business route the hard way. This is not true universally but in another generation it will be hard to find at the head of large enterprises men who don't have either professional training in management or professional training in technology.

But the greatest change in big enterprise that affects this issue that I've been talking with you about is due to a growing recognition of the public responsibility of very large undertakings. This recognition is most evident in the fact that when a great public issue arises, such as, say, international trade, or the issue of the participation of individuals in unions, it is almost always the heads of large enterprises who take what most of us believe to be a relatively enlightened point of view. The associations of small business men, by and large, have a definitely reactionary view on most of the important public issues. I am speaking now, not about partisan issues, but about broad, public policy questions such as free-trade or limitations on trade.

I look forward to arguing some of these points with you tomorrow. I'd just like to say a word to you about the good feeling one gets because there is as much creativeness in the universities and colleges today as there is because it's still possible to create a new kind of course when I thought all the courses had been invented. I used to travel around a good deal to the universities and found courses in being a mortician's assistant. I remember seeing awards given in the conventional cap and gown to men who had really been through a trade school. It's very good to see us get back to a course where all the seniors of a college get together on a single subject after having been through this process of optional courses which has become traditional.

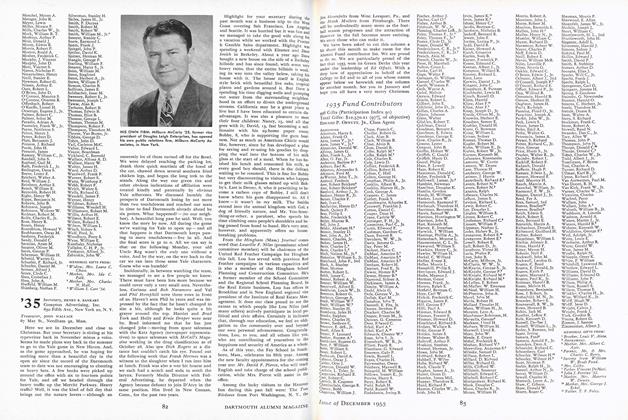

F. CUDWORTH FLINT, Professor of English and Director of the Great Issues Course, shown in the Public Affairs Laboratory. Behind him is a display on objectives and procedures of the course.

The ALUMNI MAGAZINE presents here a transcript of the Great Issues lecture delivered October 19 by Mr. Lilienthal, former Chairman of TVA and of the Atomic Energy Commission. His talk to the senior class was one of eleven given during the section of the course devoted to National Issues. Some other issues considered in this section were free enterprise, the role of government, the power of majorities, and national security and individual freedom.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCharles Ransom Miller '72

December 1953 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, w. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1953 By HENRY R. BANKART, JOHN WALLACE -

Class Notes

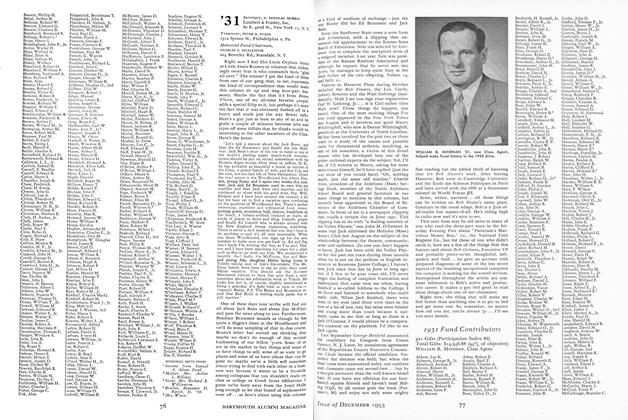

Class Notes1931

December 1953 By Lambert & Feasley, Inc., PETER B. EVANS, CHARLES S. MCALLISTER -

Article

ArticleA True Dog Story

December 1953 By A. I. Dickerson -

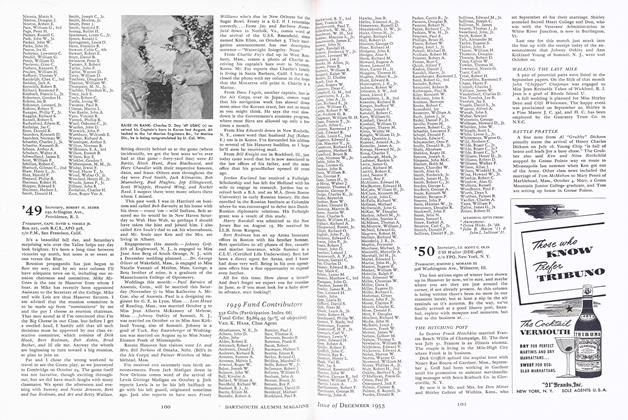

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1953 By SIMOND J. MORAND III, LT. SCOTT C. OLIN

Article

-

Article

ArticleAwarded Fellowship

November 1947 -

Article

ArticleThe Moosilauke Ravine Lodge?

MAY 1959 -

Article

ArticleNUPTIALS

OCTOBER 1996 -

Article

ArticleWinter Schedules

December 1952 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

MARCH 1966 By HARRY W. SAVAGE M'27 -

Article

Article1953 Dartmouth Parents Committee

December 1953 By WILLIAM H. COULSON, CHAIRMAN