CONSULTANT TO PRESIDENT EISENHOWER ON FOREIGN ECONOMIC POLICY"

I THINK all of us would prefer to talk about what unites Canada with Britain and the United States, but Dean Jensen and others have decreed we shall talk about the problems, and so problems it is. The problems that I shall talk about are immediately significant, but against history they are no more important, in my view, than the funny things an Englishman does with his fork, or the fact that at the moment my good friend, Sir Geoffrey, is not nearly so concerned as I am about the fact that the White Sox are 5½ games behind.

I shall talk only of economic problems. I shall not touch political questions. We have enough amateur secretaries of state in the United States at present without my joining that number, some of whom are wondrously proficient after the third highball.

I think we may talk first about problems that unite us. We have one problem in economics that is common to all three countries. Most acute, I think, in the United States, next most acute in Great Britain, but coming up strong in Canada is the inordinate pressure on society today for the payment of wages that are not represented by productivity and the addition of new wealth to the nation. I get diverted at how baffled economists are these days by our new inflation. It refuses to respond to orthodox formulae, and I think it's because of this new element; in fact, I think the key log in the economic log-jam of the future is this pressure for the payment of wages that are not represented by added wealth in the nation. To pay such wages is exactly like printing greenbacks in terms of its effect, and it will get all of us in our generation unless we stop it. And it must be stopped within the framework of freedom and by democratic process. It must not go to government regimentation.

In our country, everybody knows, the largest union in the industry sits across from the largest company in the industry. They establish a wage pattern solely on the basis of expediency without regard to economics. That immediately binds every employer in the country willy-nilly. We in Washington are doing everything we can for small business. The small business man is absolutely helpless under that form of collective bargaining. He either grants the wage increase or goes out of business. He immediately raises his price, trying to get it raised before the other fellow raises the price against him, and there you are.

In all this I blame the American public. Our people are impatient of strikes. We regard the right to strike as a sacred aspect of freedom, and we think nothing whatever of sustaining the right to refuse a wage increase and take a strike. "A plague on both your houses" is still the attitude of the American people. And until our people come to understand the issues in the strike and know in their own minds whether the wage increase is right and then stand firm behind a refusal to grant an inflationary wage increase, we shall not lick this problem.

The next issue that we share in common is the intense resurgence of protectionism in our three countries. As everybody knows, the Eisenhower administration is committed to the doctrine of the gradual and selective reduction of trade barriers in the belief that a rapidly rising volume of world trade benefits all nations and particularly the United States. In the past few years great headway has been made in the reduction of trade barriers. We in the United States, and particularly in Washington, are watching with great interest the common market idea and the free trade area idea on the Continent and in Great Britain, and we cannot help but wonder whether that will really be a great step ahead in the liberalization of trade or a furthering of the resurgence of protectionism. I, for myself, put the most optimistic viewpoint upon it. It's in the hands, in all the countries, of able and enlightened men who believe in the reduction of trade barriers. The key to this problem lies in industry in all three of our countries. . . .

We have with our friends to the north the extremely delicate and difficult question of the agricultural surpluses. You might as well face it, that is a tough one. They don't think very much of us. The United States Government is under mandate from the Congress to dispose of the agricultural surpluses which you, ladies and gentlemen, have purchased with your taxes - you're glad to do it, I have no doubt - at prices below their cost, namely, world market prices. Our friends in Canada say that we are invading their markets. We say we are doing this with extreme discretion and care. We talk with one another frequently, and so far our voices have not been raised too high, but they might be.

Now there's a new twist to this subject. It may have come to your attention that the American Congress adjourned last week. In those final mad hours they passed once more for one year Public Law 480 which is the law that authorizes our government to dispose of these surpluses for foreign currencies. We have a fine assortment of dinars, rupees, yen, and so on, and if any of you would care for some of those currencies for dollars see me after this meeting. The American business community now wants those funds in part loaned to it for investment in foreign countries. The Congress has so ordered, and the executive branch will so undertake, and the business community is not aware of the difficulties that that places on government. Briefly they are these. In the first place, it inhibits the sale of the surpluses. It's a tie-in sale. The governments that take these surpluses want to dispose of the proceeds. They want to borrow those funds in their currencies, and dispose of them as they see fit. And when we direct that 25% go to American business, that reduces the possibility of the sale of the surpluses, and they may buy from our Canadian friends. . . .

The next series of thorny questions - and boy, are these tough - has to do with our friends over at the end there on the question of trade with China and the satellite nations. You will remember that there was established among some eighteen nations, I believe, a system of control on the shipment of goods to Russia, the satellites, and China. There were two lists, one and two, of goods, the handling of which is now in dispute. There was a list of 207 items which were permissible for shipment to Russia but embargoed and forbidden as to China. This raised problems as to the Japanese, for example. The Germans - I'll leave out the British - the Germans were able to ship these goods to China through Poland and Czechoslovakia. Japan was forbidden to ship them. We and other nations were endeavoring to build a strong hand in the Pacific. I think I heard something about cutting the budget this year, and it would advance the cutting of the budget if American troops might come home from the Pacific and Japan take a stronger part in the security of our nation and all nations in that area. But Japan was forbidden these 207 items and saw the business go to Germany. They said, "What price standing at your side in the great battle of freedom and have the Germans take the business away from us?" This is one of those situations where the economic side and the political side are in conflict, and whenever that happens, my friends, economics goes by the board if political and security considerations for our country overrule it.

China is still a barbarous nation and is so behaving toward us. Our friends, the British, had recognized China; we had not. So we took the position that maybe 207 items was too much; we ought to worry that down to a hard core of maybe 25 items and stand fast. Our friends, the British, listened for almost five minutes and walked out, and said, "Nuts." They tore up the whole list of 207 items, their business community is now free to ship those items to China, and the United States business man is left alone. He is still embargoed, and will continue to be embargoed while our friends, the British, take the business. That's tough.

You said you wanted these things pointed up, didn't you, Mr. Chairman?

There is a related but different series of problems having to do with trade with the satellite countries in Europe. You will have noticed that the United States has liberalized its economic relationships with Poland, based upon certification by the Secretary of State that the government of Poland is no longer dominated by a foreign country. But take Rumania, the economic situation of which is absolutely desperate. There are two schools of thought. There are those who say that obviously trade benefits both sides, but let us withhold the benefit to ourselves in order to deprive that country of the benefit in order to bring their economic situation still lower and thus provoke revolution. There are the others who say, "Trade does benefit both sides. We are the smartest traders in the world since the days of the Yankee Clipper; let's take the shirts off their back in trade, help ourselves, but let the flow of people back and forth in the course of trade help to advance the evolutionary process of return toward democ- racy." That question will be before us urgently in the next few months and years, as to when, and how, and to what degree we shall free up our economic relationships with the satellite countries as a step toward advancing them to freedom. All this as distinguished from trade with Russia.

Then, there is one final problem which, I think, the American business community is entirely unaware of, and that is the impact of Soviet trade penetration of the undeveloped countries. That's a new thing in trade of all kinds, and it's going very rapidly. Free enterprise is up against the real thing in competition with Soviet trade penetration of a new country. Mr. Mikoyan, the distinguished Armenian who handles trade for the Soviet, is the greatest salesman in history. In the old days there was many a drummer who carried a few sidelines because the principal product wouldn't pay his hotel bill. Mikoyan carries as sidelines the entire productivity of his country. Wherever he goes, he'll sell anything, at any price. He arrives and wants to sell ten locomotives. Weil, we are very sorry; we got a better price from the Germans. What's the price? All right, I'll take 5% off that. Now who under free enterprise can go into another country and deal that way? And yet, the hazard for the American businessman is that if a particular country standardizes on the Russian type of locomotive, Russia will get all the repeat orders, all the maintenance orders. Their men will learn to run those locomotives and not our locomotives, and our grandchildren may wake up and say, "Grandpappy, where were you when they were taking those markets away from us?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

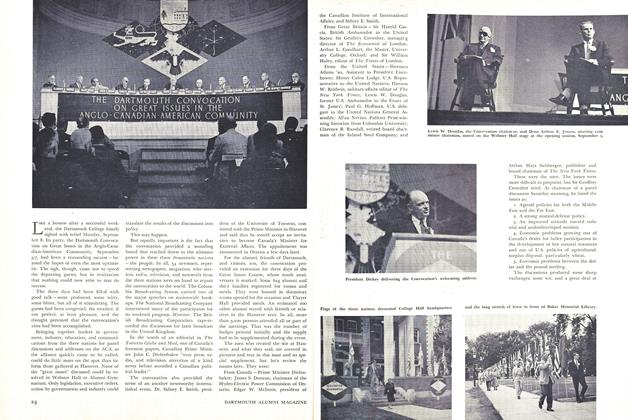

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY -

Feature

FeatureThird Panel Discussion

October 1957 By ALLAN NEVINS

CLARENCE B. RANDALL

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1961 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Big Day Draws Near

OCTOBER 1962 -

Feature

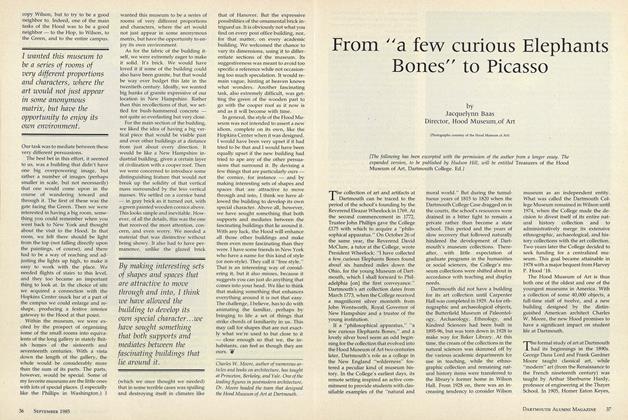

FeatureFrom "a few curious Elephants Bones" to Picasso

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Jacquelynn Baas -

Feature

FeatureGood Teaching: A Case Study

February 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureTHE 5 MINUTE GUIDE TO THE COLLEGE GUIDES

Nov/Dec 2000 By JON DOUGLAS '92 & CASEY NOGA 'OO -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Essence

MARCH 1995 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79