ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT

IN some lectures delivered about 25 years ago on the subject The Publicand Its Government, Felix Frankfurter pointed out that the American people criticize government more vigorously all the time, yet constantly give it more work to do. They belabor the state most mightily even as they expand its role. How can this be?

One answer, of course, is that we frequently play fast and loose with our political slogans. To an automobile manufacturer a public housing program may appear to be "Socialism" while a public roads program may appear to be "Progress." A labor leader may applaud a government that guarantees minimum wages while condemning a government that outlaws the closed shop. In 1951 cattlemen marched on Washington to oppose a ceiling over prices; in 1953 they marched on Washington to propose a floor under prices. Some years ago when the Federal Communications Commission was being established a spokesman for various trade and financial interests, testifying in support of the bill, complained:

An absolute monopoly controls the cable and radio telegraph service across the Atlantic Ocean; this monopoly has exercised its powers to raise rates lam personally opposed to any unnecessary government regulation of private enterprise. Yet I have reluctantly come to the conclusion that the only hope for fair treatment... lies in effective government regulation.

And only recently a presumably conservative industrialist ran a full-page advertisement in The New York Times to celebrate the triumph in the courts of a statute that compels one private businessman to sell at "Fair Trade" prices set by other businessmen. The advertisement, incidentally, referred to the system of free competition as "The Law of the Jungle."

All of which reminds me of the elderly Southern gentleman who was coming to the end of his days, when one morning the local preacher dropped in and suggested that the time had come to make his peace with the Lord and to renounce the Devil. And the old man thought it over for a while and then shook his head sadly and said, "Preacher, I sure want to make my peace with the Lord. But as for renouncing the Devil, in my condition I can't afford to antagonize anybody."

That has been the line followed in this country. Most groups have identified some government action with sin in their time. But this has not prevented them from asking for help in their turn. For all practical purposes our beliefs about the propriety and proper limits of such help have been reasonably flexible; and I think this a most fortunate condition for any people that disagrees over the "true" role of the state. When agreement comes hard, doctrinaires are dangerous.

Now let us move on to another set of generalizations drawn from history. In the record of the past there has never been a government that did not intervene in social life to some extent; nor one that regulated it completely; nor one whose role in social life remained fixed or unchanging.

Let us take the first proposition: that all governments intervene in social life to some extent. The cheap way of establishing this is to say that it follows by definition. To govern is to intervene. But if we prefer to look for evidence we find that even in medieval Europe, where many of what we today call public functions rested in private hands, rulers prescribed what kinds of cloth might be woven in particular towns and required that burial shrouds be made of wool. In the 19th century, at the high tide of laissez-faire, it often took a special act of a legislature to issue corporate charters. And in the year of our Constitutional Convention the lawmakers of so rugged a commonwealth as Vermont enacted a bill that read in part as follows:

Whereas it has been found by experience that great advantage has been taken by ferrymen demanding unreasonable prices for their services ... therefore be it enacted that the magistrates, selectmen, and constables shall meet before the first day of August annually and appoint persons for ferries and regulate the price thereof.

Let us take the second proposition: that no government has regulated social life completely. This is surely true of earlier times when even the most despotic regimes lacked the technical and administrative arts needed to regiment their peoples completely. Such regimes were authoritarian; but they were not totalitarian. There were no legal limits to their powers; but there were important practical limits. Today, man's skills are such that he can more closely approach the purely totalitarian state. He can approach it. But I wager he has not reached it, not even in the Soviet Union. For in Russia the farmer is often able to retain his personal garden plot. The family, if discreet, can carry on many of its domestic affairs unhampered. Even the great number of reporting devices and checks and balances in the police system strongly suggests that the rulers do not assume that their decisions will be carried out faithfully on each occasion.

To illustrate that government's role in social life is constantly in flux it will suffice to take two examples, one American, one British. About 55 years ago the State of New York passed a law forbidding any man to work in a biscuit, bread or cake establishment more than 60 hours in any one week or more than ten hours in any one day. The law was declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court. Mr. Justice Peckham, speaking for the court, said:

Statutes... limiting the hours in which grown and intelligent men may labor... are mere meddlesome interferences with the right of the individual.

That was the limitation placed on government a few generations ago. Today the 40-hour week is a commonplace. Not long after this New York case the British Government introduced into Parliament a bill to establish a national system of free education. An opponent rose in the House to protest:

What is it that the Honorable Gentlemen would do? Would they stuff Latin & Greek down the throats of children of agricultural laborers with one hand while taking away their bread and butter with the other?

Americans of that time would have found such sentiments bizarre indeed. But today Britain is the home of social welfare and regulatory schemes far more ambitious than most of us would be prepared to countenance.

IT is all well and good to draw upon history for these generalizations. But to come to closer grips with the question we shall have to move from historical analysis to morals. In the balance of this discussion, therefore, I shall try to do three things: First, to present a general ethical argument upon which an answer might be based. Second, to apply this argument to government action in some specific areas, such as personal beliefs and political and economic actions. Third, to evaluate some of the dangers that might accompany an expansion of government functions.

Let us begin by asking what the needs of society are. There is no mystery here. Society requires protection from enemies within and without. It requires a reasonably adequate system for producing and distributing goods; a system for settling disputes; enough customs or rules to make behavior predictable; some outlet for creative impulses; some values or beliefs that, commonly shared by its members, bind them together and enable them to face the uncertainties of life. One need not make a comprehensive list.

But in passing we can note that there is already enough on the list to make the point that government in some form is essential to social order. In this sense a wholly laissez-faire society is a contradiction in terms.

But the political realm is not co-extensive with the social realm. It does not cover the whole ground. A great many needs of society are met without benefit of government. Beyond the law are countless customs, beliefs and relationships that no government has ordained. As Maclver puts it:

Everywhere men weave a web of relationships with their fellows, as they buy and sell, as they worship, as they rejoice and mourn. This greater web of relationships is society. ... Within (it) are generated many controls that are not government controls, many associations that are not political associations, many usages and standards of behaviour that are in no sense the creation of the state.

This distinction between society and the state is of utmost importance to democratic theory. Where it is not made, where man's whole being is wrapped up in the state, he can never claim rights against it. This is shown most poignantly in Plato's account of Socrates in jail. Socrates, accused of corrupting the young with false doctrine, is awaiting execution of his sentence. His friends beg him to escape. He refuses. The idea makes no sense to him. He puts himself in the place of the authorities and argues their case:

Can you deny that you are our child and slave? ... You are not on equal terms with us Has a philosopher like you failed to discover that our city is more to be valued and higher and holier far than mother or father? ... And when we are punished by her ... the punishment is to be endured in silence.

Granted that the state injures you. Granted that It passes unjust sentence:

Will you then flee from well-ordered cities? ... Is existence worth having on those terms?

That is the ultimate point for Socrates. Is existence worth having on those terms? Can life be regarded as meaningful outside the state? The answer is clearly no. Man is therefore the child and slave of his polity.

But in a democracy state and society are distinct categories. The state is simply an agent of society and its government discharges those functions that society confers upon it. This still does not tell us what those functions should be. Let us, therefore, examine that question from a moral standpoint.

The moral premise of democracy is the worth of each person. A democrat believes that some value resides in each individual, whatever his abilities, whatever his shortcomings, whatever his attainments. You either see this, or you do not. You certainly cannot prove it. You simply believe it. It has been wisely said that you believe it as a matter of faith — or of hope — or of charity - or of all three.

Believing it, you must judge human institutions, including government, according to whether they enable men to maintain and develop their worth, to grow in ability, maturity, and responsibility. Institutions must be judged according to whether they enable men to develop their capacities for - let us not be bashful about the words - for gladness, for goodness, for taste and spontaneity, for respect and love.

Now society provides many opportunities for this kind of growth. But men being a trifle lower than the angels, society also contains many threats to such growth. The mission of the state, then, is (1) to enlarge the opportunities and (2) to check the threats. The mission of the state is to foster the favorable conditions and to throw up walls or fences around the unfavorable conditions so that human personalities can develop inside those walls. This is its two-fold mission. David Low, the great British cartoonist, put it most simply a few weeks ago, when he said the purpose is "To prevent people from biting one another, and to give their souls a chance to grow."

What must a state do to accomplish this mission? In general terms the answer is clear. It is stated well enough in the Preamble to the Constitution. The government is designed to:

establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty ...

If the mission of the state is clear, and if the general activities that support that mission are plain, then the importance of the state is also evident. Its claims to our allegiance are evident. I wish to dwell on this point because it is not always adequately recognized. Many Americans deep down in their hearts agree with Tom Paine when he said:

Society is produced by our wants; government by our wickedness.... Society is a blessing but government is but a necessary evil.

From this view I must dissent. Recall that part of the state's mission is to check threats to the development of individual personalities. Now, each person's right to grow may be respected by most other persons most of the time. But it will not be respected by all other persons all of the time. And it is the particular and noble function of government to try to close this gap by law. The work of government is to make certain that I respect your rights in exercising my own. I have the liberty to move my arms as I will, and even to clench my fist. But my right to swing my fist stops just short of the point where your nose begins. The law, if you please, is a fence around your nose; and surely this fence is a blessing rather than an evil.

One broad conclusion about the proper limits of government can be drawn from the argument thus far. The law must never seek to impose more than a minimum standard of human conduct. It should not attempt to require the ultimate in moral behavior. It ought not to prescribe the whole duty of man. If it does, no room is left for freedom of choice, and without freedom of choice, the development of personality is impossible. Human faculties, as in the case of muscles, must be exercised in order that they may be improved.

Plato - to use him as a whipping boy once more — did not accept this proposition. For him the purpose of the state was to make men good. From this premise he proceeded to regulate every detail of social life. Marriage, careers, culture, all were to be managed to produce human excellence. He asks:

Shall we just carelessly allow children to hear any casual tales ... and to receive into their minds ideas the very opposite of those we should wish them to have when they are grown up? If not, then the very first thing will be to establish a censorship of the writers of fiction.

Homer and Aeschylus are banned for their inappropriate descriptions of the gods. Sculpture and building are regulated lest the citizens be corrupted. Flute players are outlawed and with them certain musical harmonies, the lonian and Lydian, because they express softness and indolence. Men are forbidden both Sicilian cooking and Corinthian girl friends!

All this sounds very quaint. But I am sure that modern dictators find it full of relevant lessons. Or consider its application to the classical failure of government action in American history: the attempt to curb drinking. Why did this fail? It failed because it went further than an effort to deal with such grosser consequences of drunkenness as breach of the peace and desertion of family. It actually tried to impose on people a notion of goodness that many of them did not share. It tried to deprive them of the right to make their own moral choices in a matter than can be purely personal. So it has also been with many Blue Laws that are never enforced, and with some of the more archaic laws relating to sexual matters.

Of course, to say that the law should not seek to impose maximum standards of morality raises as many questions as it answers. Would Fair Employment Practices legislation, for example, constitute an effort to set standards of conduct so high that men would be unwilling to follow? Or, more important, so high that men could follow only by surrendering all freedom of moral choice? I personally do not think so. In his great work, The American Dilemma, Myrdal demonstrates that white men are better prepared to acknowledge the equality of Negroes in legal and economic matters than in personal or social relationships. FEPC, in other words, does not seek to batter down the wall of prejudice at its strongest point. It does, however, seek to provide the Negro with the conditions of self-respect by forbidding white men, in the exercise of their rights, to deprive him of his. In so doing it relieves white men of the serious tension that grows out of the inconsistency between their democratic creed and their actual conduct. In short, I find distinctions between the FEPC case and the Prohibition case. If others do not find such distinctions, that in itself will illustrate that there are marginal cases where the application even of widely shared principles is bound to be controversial.

WE turn now to more specific cases. May the state enter the area of our beliefs? May it dictate our religious, moral or aesthetic convictions? We answer, "Of course not." But it is important to be clear about the reasons. It is plain that such convictions bear a peculiarly intimate relation to our personalities. It is also plain that compulsion here is in the most fundamental sense pointless; for the whole value of a belief is the sincerity with which it is held. Coercion in this area can produce only automatons or hypocrites. Compulsory devoutness or goodness or refinement are meaningless notions.

May the state enter the area of our political actions? Has it a right to intervene in the process of self-government by limiting the expression of political beliefs, the organization and functioning of interest groups, electioneering, or other functions essential to the making and unmaking of governments? Our caution here stems from two concerns. First, there is a danger that any state that embarks on such a course will in the end seek also to dictate private convictions. Second, there is the certainty that it will deprive its citizens of the opportunity to develop the political wisdom that only the experience of selfgovernment can provide. But here, also, there are difficult problems. May the state exercise closer supervision of the political process in time of emergency or social unrest? The issue could be drawn starkly if it ever came to a choice between a free political process and national survival. Our Founding Fathers touched the margins of this dilemma when they provided that the privilege of the writ of habeascorpus may be suspended "when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it." Other men have sought to develop full-fledged theories of constitutional dictatorship to meet the problem. But no obvious institutional answers have been found. Nor can moral argument carry us much further on the point.

FINALLY, what about the economic realm? If the purpose of the state is to enlarge the opportunities for self-development and to check the threats thereto, has this purpose been advanced or retarded by the recent growth in the economic functions of our government?

On the whole I would argue that it has been advanced. The state has enlarged human opportunities by providing services that society has desired, but that society could not secure through private action because individuals either lacked the necessary resources or did not want to risk them. Many familiar programs can be explained in these terms, including public education, highway building, the census, old-age insurance, unemployment relief, and so on. An interesting example appeared a few months ago when the Atomic Energy Commission announced that it was going to build and test a reactor to make electric power. It was calculated that this might cost from $20 to $50 million and that operating costs might be at least five times as high as existing commercial costs. Private industry was asked to do the job but refused. Consequently the financing and policy control will come from government while the actual work will be done under contract with a private firm.

That decision did not create wide public debate. But as a people we disagree over whether the government ought to finance housing or health programs. From the moral standpoint, of course, these issues stand on the same ground as public control of education or public financing of a nuclear reactor. Nothing in the nature of democratic theory requires the state to avoid such activities. The only relevant questions - and I do not mean to imply that they are not terribly important - are questions of fact. For example, does society really desire more opportunities here than it now has? Does society desire such opportunities even at the expense of other services, like national defense, that also lay heavy claim to limited resources? Are private individuals really unwilling or unable to perform these functions? This list does not exhaust the questions that must be asked, but it illustrates the general kind.

The second large category of economic functions performed by the state consists of programs most of which are designed to check threats to individual self-development. Under this heading I would place measures to prevent waste of resources, sale of impure food, establishment of unfair rates, prices or wages, or utilization of unfair methods in commerce or in the securities or labor markets. To a great extent these regulations reflect society's efforts to cope with the gigantic private organizations that have sprung up within modern nations, organizations that even when acting in good faith may carry misfortune to men far away, organizations that when acting in bad faith have got to be restrained by law if social existence is to remain tolerable.

In this area of regulation one major moral problem must be noted briefly. It arises because public regulation is frequently accompanied by punitive sanctions. Wherever such sanctions are involved, the importance of due process is paramount, due process not only in the courts but in legislatures and before administrative agencies. Men cannot develop their powers or grow in self-respect when they are subjected to arbitrary procedure by public officials.

I HAVE put off until now any mention of the dangers that may lie in constant expansion of government's role. But no sensible man would deny that they exist. However legitimate a function may be on moral grounds, grave practical difficulties may arise in the attempt to perform it. The effort may boomerang altogether. Or it may succeed only at the expense of other important social needs.

This is tricky terrain, however. I have heard it argued that some citizens will grow lazy if they succeed, through political initiative, in securing a large measure of personal welfare, while other citizens will grow more enterprising if they succeed, through economic initiative, in securing the same blessings. The logic of this position escapes me. Indeed I am persuaded that terms like "initiative" and "incentive" must be used with utmost caution. For one thing, they often beg the question of whose initiative and incentive we are talking about. For another, we do not yet have enough careful studies of the actual effect of particular public policies on the motivations of particular individuals or groups.

Words like "bureaucracy" may be more relevant. Government is often inflexible, aloof, full of procedural rigmarole, and so on. But to some extent these things are necessary; where unnecessary they often fall into the category of minor nuisances. The larger problem is whether bureau- cracy will continue to accept its new political masters as they appear; and this the civil servant has seemed ready to do in every modern state, including, let it be noted, Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany.

There remain some major problems of Big Government that have received less popular attention than they deserve. Let me sketch a few of them in closing.

One is the difficulty of combining considerable control over the national economy with effective participation in international economic life. Once a national planner has matters arranged to his satisfaction at home, it is only human of him to wish to protect his nice schemes from disordering foreign influences. Following a short-sighted conception of his fellow-countrymen's welfare, he may therefore start down the treacherous path of economic nationalism. Few impartial students would deny that this has been one troublesome aspect of Great Britain's recent experiments in socialism.

A second problem is that as governments extend their economic role it becomes increasingly clear that their decisions help determine the allocation of resources between current consumption and capital formation. In a democracy these decisions are made by men responsible ultimately to the electorate; and the electorate may exert irresistible pressure to enjoy the fruits of its labor in the here and now, hoping that the future will take care of itself. In Soviet Russia this problem has been solved by dictatorship, though even there we are beginning to see some signs of a response to the popular clamor for consumer goods. In Great Britain, if the problem has been solved at all, it has been only because of the unique self-discipline of a uniquely homogeneous people. I should hesitate to predict that we could do so well under similar circumstances.

A third problem is more technical. Can administrators do as effective a job as the price system in making the hundreds of thousands of decisions involved in the allocation of resources. Administrators did a respectable job during World War II; but they were tackling only a part of the whole economy and they had the advantage of reasonably clear and acceptable goals.

A fourth problem is whether an increase in the number and importance of premeditated economic decisions will lead to more social conflict. When decisions are not planned, when they are made by the famous "invisible hand" of the market, men may be more forebearing if they do not like the results. But when administrators make decisions deliberately and men do not like the results, they are in a position to name the "guilty" one. He can be accused of stupidity or malice. This will not make for social harmony. Also, as government bites more deeply into economic life, each man and group acquires a bigger stake in public policy, and pressure politics is bound to increase. Men may become more concerned with the political opinions of their neighbors, less tolerant of those who disagree, and less gracious about accepting political decisions. All this could put the human capacity for fellowship to severe test.

The last problem I wish to comment on relates to the machinery of government itself. The practicable range of public functions depends not least on the adequacy of our political, legislative, and administrative institutions. A pessimist would say that our present government machinery gives such encouragement to special interests that no genuinely public policy can emerge, but only the policy of a farm bloc that has captured a Congressional committee, a railroad group that has captured an administrative agency, and so on. Upon this view any future growth in government can only lead to less consistency, more log-rolling, and greater inequity. If this is true we are in a bad way; for it does not seem obvious that the government of the future will be Small Government. Personally, however, I am optimistic enough to believe that institutional reform must come as government acquires new burdens and as men realize that the old arrangements are growing costlier and more inadequate.

Professor Radway's article is based upon the lecture he delivered in the Great Issues course during the first semester, with the title "To What Extent Should Society's Needs Be Met by Government?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIn the Public Eye

March 1954 By FRANCIS BROWN '25, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1954 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1954 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, CARLETON BLUNT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

March 1954 By LT. (JC) ROBERT D. BRACE, ENS. DONALD E. MACLEOD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939

March 1954 By JOHN R. VINCENS, DON C. WHEATON JR.

LAURENCE I. RADWAY

-

Books

BooksTHE POLITICS OF DISTRIBUTION.

June 1956 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksFOREIGN AID AND AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY: A DOCUMENTARY ANALYSIS.

JANUARY 1967 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksMAN INCORPORATE, THE INDIVIDUAL AND HIS WORK IN AN ORGANIZED SOCIETY.

November 1968 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Feature

FeatureCITIZEN SOLDIERS

October 1973 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksNot in the Stars

January 1976 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksThe New Right

November 1979 By Laurence I. Radway

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryHandsome Facade

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureGame Changer

NovembeR | decembeR By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Stuff of Art

October 1992 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

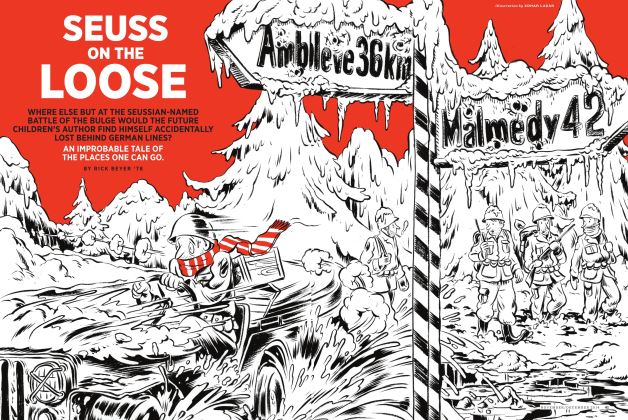

FeatureSeuss On the Loose

NovembeR | decembeR By RICK BEYER ’78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Unknown and Unsung Undergraduate Days of Stephen Colbert ’86

July/August 2008 By Robert Sullivan ’75