ONLY last fall when Mrs. Mary Smalley sedately stepped out of the elevator at the Hanover Inn, the youthful voice of a middleaged gentleman who had caught sight of her cried, "Short cheer, Smalley."

More than a quarter of a century ago the cheer originated in that club at 5 College Street which generated more fun and developed more celebrated graduates than a dozen classrooms. As a Dartmouth tradition, Ma is immortal; but the club itself is already rubble and dust. Grass will be growing this spring from the foundations that served as ballast for more hilarity, deviltry, and mothering than any others in Hanover.

Refer the matter to a trustee i£ you like. Sig Larmon '14 can tell you stories about the eating club that would arouse the envy of the manager of Chambord's in Paris and evoke the shades of Will Rogers, humanist, and Ring Lardner, humorist. That popular wit in athletic and alumni circles, Bill McCarter 19, Smalley cashier, can give you stories about financial legerdemain, McCarteresque, Smalleyesque, and burlesque, all ringing as true as a National cash register.

The throne on which the Queen Mother Smalley sat and ruled was a kitchen chair on the north side of the kitchen. Partly by seeing, partly by hearing, and partly by intuition she knew what was going on in the pantry, on the porch, in the cellar, in the dining rooms, and upstairs in the boys' rooms. The Queen Mother was ambidextrous and bilingual. With appalling accuracy she could throw articles with either hand and epithets in proper English or improper Dartmouthese. With such lightning speed in both weapons of attack who may say which was the more headsplitting or sidesplitting?

The pace was fast; Ma set it; and the boys carried it on. One headwaiter operated only by scaling dishes from the pantry to the tables and by engaging only waiters baseball trained who could catch them with one hand and with the other place them perfectly in order on tables. In the days when mayonnaise was hand beaten with an egg beater, Ma Smalley gave it a whirl and turned it over to a student-helper who after only a few seconds complained that his arms ached with all that work. He got the egg beater filled with mayonnaise smack in his face in Mack Sennett style.

She liked high jinks too. On occasion she would guffaw with laughter at horseplay, and she was not above horsing around too. Eager to make the movies one night, she found that a group of eight Smalley Club members had seen her coming and had formed an impenetrable phalanx which prevented her from reaching the ticket window until she had bought each one of them a ticket also. T hey knew how generous Ma was. Any fellow could wangle a buck out of her, and sometimes she got it back and sometimes she did not. Sometimes she lost as much as $80 a boy when her big heart was moved to expansiveness by stories of sickness, bad luck, and family privations, but she gained $80 worth of pleasure and never found herself in debt $80 worth to disillusion.

But Ma was no sentimentalist. In the early days of the Club large pans of grease with lye added from which soap was made stood on the shelf. A club member viewing the delightful concoction cried out with the lyric fervor of a sweet tooth, "Hooray! Penuchel May I have some, Mrs. Smalley?" He took a big bite and then spat high, wide, and unhandsome. Today he likes to compare the taste and the burn of that penuche to various kinds of illegal hooch of the bathtub era.

Mrs. Smalley was and still is a sort of female Chaucer with stories from infinite numbers of Hanoverian pilgrimages with Northampton detours, a Wife of Bath enjoying gossip, a female Rabelais revelling in pungent words, a female Montaigne with miniature oral essays on human frailties and stoicisms, a combination of World Almanac perpetually brought up to date and an Encyclopedia Dartmouthiana.

In short, Ma Smalley is a unique woman; Hanover has never produced another; and Hanover never will. Just think who ate at her table. There were the faculty; James Dow McCallum (English), Harold Rugg '06 (Librarian), Peter Dow (Graphics and Engineering), Frederick Page '13 (Botany). There were the medics: Jim Smead '21, John Milne '37, Frank C. Moister '37, and Kendall Stearns '37. Then there were the assorted athletes and big men on campus or popular celebrities: Walter Wanger '15, Dan Coakley '16, Bob Paine 17, Dick Holton '18, Ken Gilchrist '19, Zach Jordan '21, Rog Wilde 'si, Bob Booth '22, Charlie Zimmerman '23, Casper Whitney '24, Ed Dooley '25, Bill Farnsworth '26, Josh Davis '27, Jack McEvoy '28, Carl Spaeth '29, Carl Haffenreffer '30, Bill Phinney '3l, John Sheldon '32, Bill Alton '33, Walt Crandall '34, George Colton '35, Don Erion '36, Wayne Ballantyne '37, Merrill Davis '38, Bob MacLeod '39, Howard Stockwell '40, Bob Lempke 41, Charlie Moore '42, Bill Chilcote '43.

And then there were the famous coaches - Jess Hawley '09, Jack Cannell '19 and Harry Hillman - and Red Blaik's football players during the eight years that he brought West Point results to Hanover.

Ma Smalley boarded about 100 boys each year, and 35 earned their meals by waiting on tables or working in the kitchen. In 1914 board was $3.50 a week, and a student could eat all he could hold, and that was plenty. In 1920 a loud cry went up about the high cost of living. Just imagine: three meals a day with meat at two of them, and she had the nerve to ask $5 a week. When Mrs. Smalley regretfully went up to $7 a few years later, the cry became a bellow.

Students who roomed at Ma's had a cheerful way at bedtime of ransacking her ice chest, turning on her toaster, helping themselves to butter, and downing quarts of milk — all at her expense. She blew up once when a boy suspecting of stealing money elsewhere gave hunger as his excuse; he was not getting enough to eat at Smalley's. It was considered to be the most ludicrous alibi of a whole college generation.

Ma never tattled or complained about her boys. She interceded only twice with college authorities in a request for favors for them. She went once to Prexy Hopkins about one of her greatest favorites when Mr. Hopkins had firmly made up his mind to fire him for getting conspicuously drunk at a college dance with prominent patronesses present. She succeeded in saving him. The second time she failed. A senior was not going to get a degree because of a low grade in history. Only because he pleaded with her so long and so pitifully she telephoned the professor.

"Mrs. Smalley," said the professor, "What would you do if you were a professor and a student kept cutting, slept through all your lectures, and showed abysmal ignorance on the examination?"

With characteristic forthright honesty she gave her answer: "I'd flunk him."

Ma Smalley ran an eating club at Dartmouth College for thirty years. She closed her doors in 1944, and the College bought the property. Since then while the building lay unpainted and derelict, the target of small boys with stones who hate glass, she has made sandwiches elsewhere, presided at coffee hours and teas, nursed the sick and the dying, including herself through a couple of bouts of pneumonia which would have killed a weaker woman. She is now housekeeper for a professor of English.

Before his house once in a while long automobiles with sleek lines and shiny paint draw up. Well groomed business or professional men from New York, Chicago, or San Francisco emerge, and on their lips are the words that keep resounding through so many decades:

"Short cheer, Smalley."

Ma Smaliey of Dartmouth eating club fame,

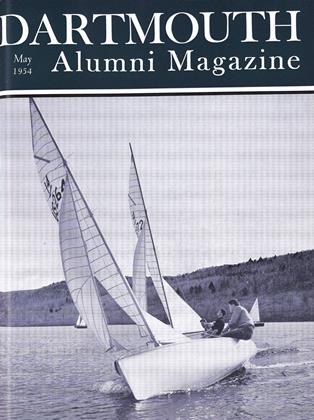

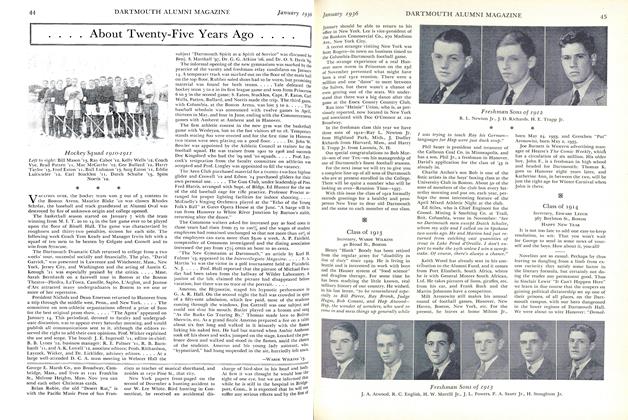

Some Smalley Club members in 1922.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE CREATIVE ARTS

May 1954 By IRWIN ED MAN -

Feature

FeatureSinging Ambassadors

May 1954 By ROBERT K. LEOPOLD '55 -

Feature

FeatureThayer School's Fire Bug

May 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureON THE AIR 16 Hours a Day

May 1954 By DONALD R. MELTZER '54 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

May 1954 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, GEORGE E. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON

JOHN HURD '21

-

Books

BooksTHE OFFENSIVE GOLFER

FEBRUARY 1964 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

OCTOBER 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksLAUGHTER AND TEARS.

FEBRUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE CARIBBEAN INCLUDING PUERTO RICO AND THE VIRGIN ISLANDS.

JULY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksOHIO AN ARCHITECTURAL PORTRAIT

October 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBUCKS COUNTY: PHOTOGRAPHS OF EARLY ARCHITECTURE.

January 1975 By JOHN HURD '21

Article

-

Article

ArticleSPIQUE MACINTYRE SAYS

May 1942 -

Article

ArticleA Life Spent in the Company of Books

APRIL 1996 -

Article

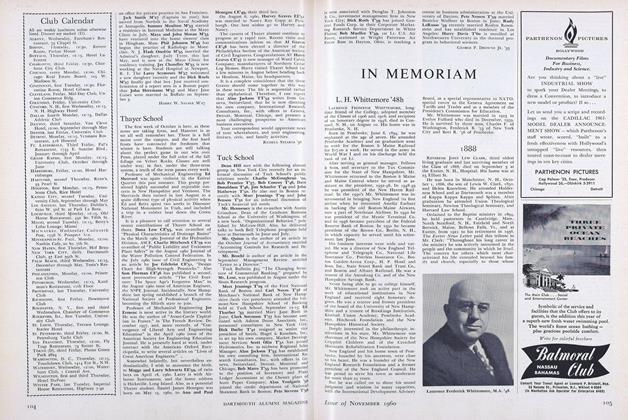

ArticleDartmouth Undying at Noon

JANUARY 1998 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

November 1960 By GEORGE P. DROWNE JR. '33 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

April 1955 By ROLF C. SYVERTSEN '22 -

Article

ArticleAbout Twenty-Five Years Ago

January 1936 By Warde Wilkins '13