IT HAS BEEN more years than I care to remember since I went to dancing school in the old and famous Hamilton Hall in Salem, Massachusetts, which must have been no stranger to the Peabody sisters. Dick Southwick '20 will remember, with pleasure I hope, those days, too. Also our almost weekly trips to the Essex Institute, the Peabody Museum, the House of Seven Gables, Chestnut Street, etc. I must go again before long and the stimulus to do so has been supplied by a book which kept my interest unflagging to the end: The Peabody Sistersof Salem, by Louise Hall Tharp (Little, Brown, 1950).

I can't remember when I read through a Book-of-the-Month Club choice. The selection group must have been smarting under criticism for at last they have made an adult choice.

The three Peabody sisters were really something, and how they escaped a biographer for so long I shall never know. As most critics have said, Elizabeth, the unmarried one, the gallant one, the amazing one, really steals the honors, though I lost my heart entirely to Sophia, the "delicate" one, who married the great Nathaniel Hawthorne, and who lies buried across the sea in Kensal Green in London, while her husband lies in Sleepy Hollow in Concord, Massachusetts. A pity they are separated. Mary Peabody finally got her Mann, and the story of their experiences at Antioch College in Ohio where Horace Mann was the first president is alone worth the price of the book.

You will also learn that Margaret fuller's conversational classes were held in Elizabeth Peabody's bookshop on West Street in Boston; how Sophia felt that Fields the publisher had cheated her out of royalties due her after her husband's death; how Thoreau sold Hawthorne the boat that he and his brother John had taken up the Concord and Merrimac Rivers; the characteristics of what Santayana has called the "genteel tradition" (and there is much to be said for it), and many other things. Thanks to Mrs. Tharp for a delightful and most informative book.

I quote: "The artist, like the saint and the criminal, tends to be maladjusted. His sensitivity alone forbids him to accept unquestioned society's rules and taboos, its standards and ethics; for him its synthesis is either too exclusive or too inclusive. According to his temperament and capacity he seeks, consciously or not, to create a synthesis of his own. Essentially it is a rival one. He becomes a revolutionary, and society reacts with thebrutality engendered by fear."

This shrewd statement introduced me to a new and interesting biography: Swinburne: A Biographical Approach, by Humphrey Hare. The author explains the synthesis Swinburne created for himself as the direct result of an aberration he suffered known as algolagnia (a word not in my 1925 edition of Webster's Collegiate Dictionary). You must learn about algolagnia on your own, though it is well known to psychiatrists and is known in Europe as le vice anglais. Ah entertaining and even enlightening book about a poet I've never been able to read.

I have reviewed Ned Calmer's TheStrange Land in another place, but suffice it to say here that I think it is the best American war book I have yet read about World War II; with reservations, this includes The Naked and the Dead and The Young Lions. This book tells of an attack on the Siegfried line in the autumn of 1944, and is written with great integrity in its desire to tell the truth.

With every succeeding book of Osbert Sitwell's my respect for him increases as a pure literary artist. I have just finished his book of short stories, The Death ofa God, and it is really top-flight stuff.

I asked Sidney Cox to write something about Dilys Laing's new volume of verse. He writes: "Dilys Laing's latest book of poems, Walk Through Two Landscapes (Twayne Publishers Inc., New York, $2.00) will charm, shock, delight and amuse many readers. Thought-provoking, emotion-deepening and perception-sharpening, these poems are respectable as compared with Emily Dickinson's; no other woman has written more admirably in ail respects, and few have written as honestly or with such sinewy grace. The poems touch adult love, growth, adventure, cruelty, motherhood, death, religion, prudishness, primary realities and primary differences. The quick eye/ .... looks aridlooks away lest all should vanish/scaredand offended by a gross regard. Some of the poems are fully felt. Some are crisped by acid wit. Some leave the reader murmuring, 'Nearly,' 'Roughly,' and 'Almost.' Some are impressively based and balanced, and humorously serene. There are warm rhythms, apt surprising images, and realizations taking on for the first time a living flesh of words. In Walk ThroughTwo Landscapes a woman is becoming a poet. A poet is becoming a full woman. Old selves are being outgrown, and old traumas are being self-healed. If certain poems had matured longer they might have been written from a point of arrival instead of describing a destination desired. Achieved skill in living is greater than aspiration, but readers can take pleasure in groping with a poet, who, like them, is on the way."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

March 1950 By OSMUN SKINNER, JOHN PHILLIPS, JOHN E. FLANAGAN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

March 1950 By HENRY R. BANK ART JR., FREDERICK T. HALEY, ROBERT W. NARAMORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938

March 1950 By JOHN H. EMERSON, WILLIAM H. MCMURTRIE, ROBERT H. CARSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1950 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

March 1950 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Books

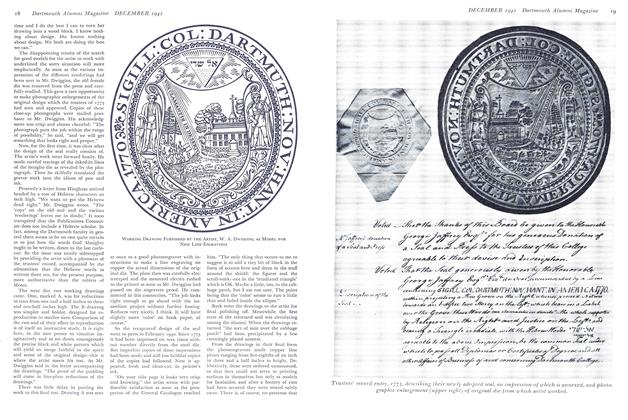

BooksDEXTER

December 1941 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1947 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE EDUCATION OF YOUTH AS CITIZENS

July 1947 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1950 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1953 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1951 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleNOTES

November, 1914 -

Article

ArticleA SUCCESSFUL PROM

June 1916 -

Article

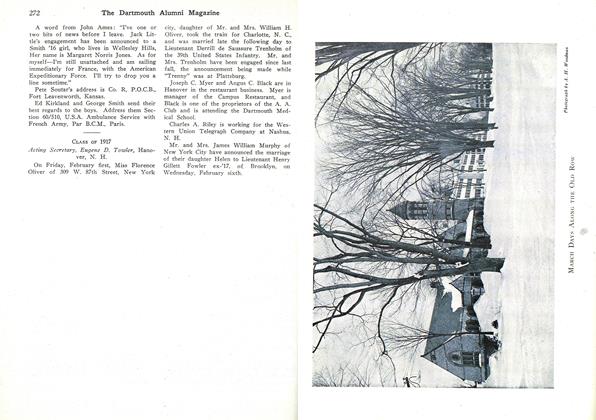

ArticleMARCH DAYS ALONG THE OLD ROW

March 1918 -

Article

ArticleClass of 1994

July/August 2006 By Allison Caffrey '06 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

December 1959 By HARRY W. SAVAGE M' 27 -

Article

ArticleReport from the Council

APRIL • 1987 By Mark P. Harty '73