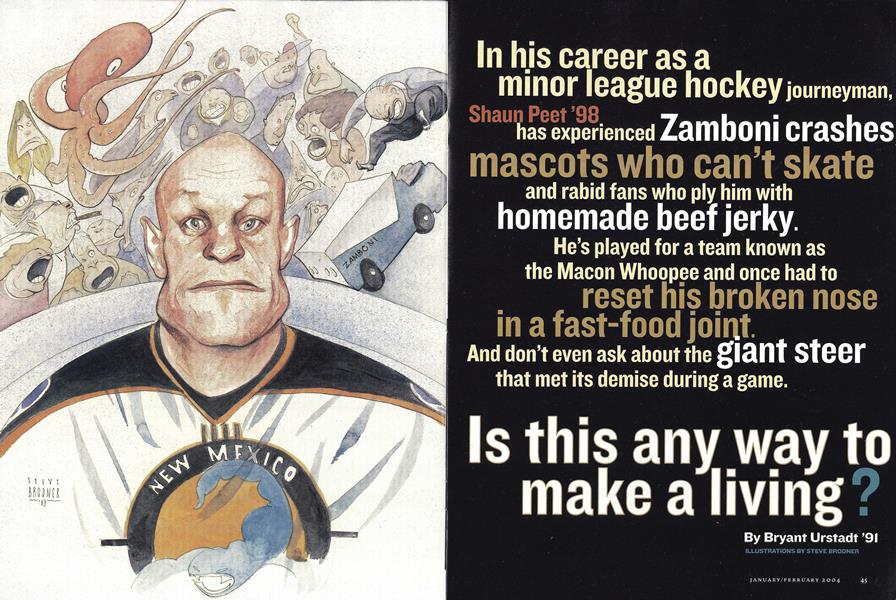

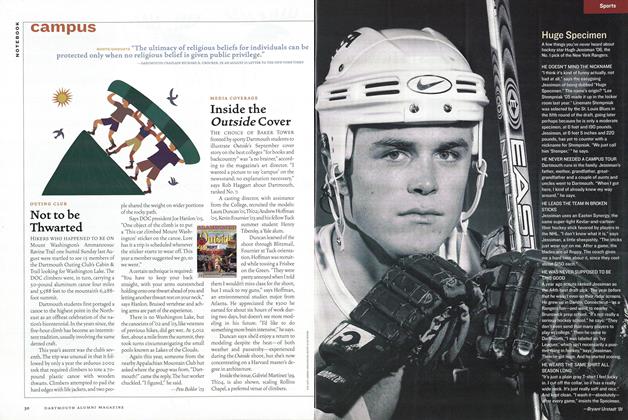

In his career as aminor league hockey journeyman,has experienced Zamboni crashes mascots whs can't skate and rabid fans who ply him with homemade beef jerky He's played for a team known as the Macon Whoopee and once had to set his broken nose And don't even ask about the giant steer that met its demise during a game.

WHEN HE MADE ROAD TRIPS WITH THE DARTMOUTH hockey team, Shaun Peet used to pass the Providence Civic Center, home of the farm team for the Boston Bruins. "We'd go by and I'd just say to myself, 'I would do anything to play one game there,'" remembers Peet.

The Providence Bruins play in the American Hockey League (AHL). While the 600 best players in the world play in the National Hockey League, the next 600 skate in the AHL, some earning more than $500,000 a year—and hoping to be promoted to the big league. For an Ivy League defenseman who sat on the bench for about half his college games, playing in the AHL was about as likely as playing in the New York Philharmonic. Still, Peet figured it was worth a shot.

So after playing four years at Dartmouth, he went to Texas. It was only a mildly crazy plan. Down on the coast in Corpus Christi, a start-up team called the IceRays, a member of the newly minted (and now vanished) Western Professional Hockey League (WPHL), needed rugged defensemen. Peet, who stands 6 feet 2 inches and weighs 220 pounds, fit the bill, so the team took a chance and signed him in 1998.

Corpus Christi and the WPHL were still a long way from the AHL. Make that a long, long, long way. There's a hierarchy in the hockey leagues, and most of the player movement among them is downward. While the youngest, brightest prospects play in the AHL, the next step down is the East Coast Hockey League, followed by the WPHL.

The IceRays played in an old rodeo barn, about 20 yards from the Gulf of Mexico. The average player earned about $500 a week, sometimes as little as $320. There wasn't quite enough room for a full-size hockey rink. The announcer sat sideways by the boards, making his calls over his shoulder. The mascot, Sugar Ray, wore a giant blue foam head and a velour tail—and had never been on skates. It was fun watching him try to stand up.

Texans, too, were just getting used to the whole notion of ice. After cleaning the ice, the Zamboni would dump the snow at the base of a palm tree. Once, during a game, the Zamboni driver was drunk and he drove the Zamboni right through the boards. "We were sitting on the bench," says Peet, "and we were like, 'Don't you think he should be slowing down right about now?' But he didn't." In Laredo one time, the fans sat patiently after the end of the third and final period in the game, waiting for a football-style fourth quarter, which would never come. Another time, in Belton, a team held a guess-the-weight-of-the-steer contest between periods. They trotted out the steer and it promptly fell on the ice and broke its leg. There was no hope for it. Women and children were asked to leave the arena. The animal was shot and dragged off, the women and children filed back in, and the game was on.

The lack of hockey tradition in the Lone Star State didn't mater much. IceRays fans were hysterically supportive of their only professional sports team. They made the team beef jerky for road trips and followed along in pickup trucks. When things were going well during a home game, they threw stingrays on the ice. Once, when things were going really well, one guy threw his prosthetic leg on the ice.

Peet traveled all over the Southwest, riding on the team bus through the night to play teams such as the Shreveport Mudbugs, the El Paso Buzzards and the Lubbock Cotton Kings. Many of the players spent the rides playing schnarpels, a low-stakes card game known only to hockey players. Peet decided to catch up on his reading. He made up a list of 50 books he thought he ought to have read during all the time he had been playing hockey, books such as Jane Eyre, A Tale of Two Cities and Atlas Shrugged. He read them all.

Then there was the hockey. It was different from Ivy League hockey. For one thing, there was fighting, which was fine with Peet. In the Ivies, fighting is strictly forbidden, but in the professional leagues, it's just another part of the game. Proponents of fighting claim that the prospect of a fight actually keeps the game cleaner, discouraging players from trying dirty tricks like slashing another player with his stick or elbowing someone in the chin.

"I fought before Dartmouth, and I was quite happy to get back to it," says Peet, who played the tough guy in the junior leagues while growing up on Vancouver Island. "I wasn't an outstanding skater, and I knew that's how I was going to get where I wanted to go." Sometimes Peet would fight twice in one night, sometimes not for a month. In some ways, fighting really does keep the pro games cleaner, says Peet: "As far as how many times you get stuck with a stick per game, college beats em all hands down. I'd come out of college games covered in cuts. There's no fighting, so there's no justice. In college hockey, guys just do whatever they want out there."

In a fight, it wasn't uncommon for him to break his knuckles. "Toward the end of the season," he says, "I wasn't too eager to knock on doors." There is a bright side to a broken set of knuckles, though, says Peet. "When they heal, they're stronger."

Speaking of injuries, the team doctors in the WPHL seemed to have trained by watching old Westerns. Their treatment was barely a half-step above offering a belt to bite and cleaning a wound with whiskey. Once in Waco, playing the Waco Wizards, a collision left Peet with a nasty cut that ran all the way from the far side of his left eyebrow to his nose. "I think the guy who stitched me up wasn't actually a doctor," says Peet. "I think he might have been a veterinarian or something. He put about five stitches where I needed 25. I've got a big scar there now, not that I was going to be entering any beauty contests or anything. The only one bothered by it is my mother."

The helpful doctor also forgot one thing. When Peet was at a McDonald's after the game, one of the older guys pointed out that Peet's nose was all crooked. The veteran told Peet to fix it, or it would stay that way. He showed him how. Says Peet, "You just put your thumbs on either side of your nose and push hard. So I went into the bathroom and looked at myself and went 'yeesh' and reset my nose."

In general,Peet has been lucky with his injuries, though he's had surgery on his shoulder and knee. He's avoided every player's worst nightmare, the career ender. Of course, unlike many of the guys in hockey, he has some education under his belt, allowing for some post-hockey options. "I see a lot of guys who skipped college to play hockey," says the psychology/sociology double major. "They have absolutely nothing to fall back on. If they get hurt, they're done, with nothing. You can see the fear in their eyes when they get injured, and I'm not just being dramatic."

Fighters are always popular with the fans, and Peet attracted a bit of a following. So when the WPHL decided to put together a calendar, league officials asked Peet to pose. The press agent took him to a beach and put him on a SeaDoo in the surf off Corpus. She said it was going to be like a firemen's calendar, and would he take off his shirt? Peet had always liked firemen, so he went along. Then the calendar came out—and he was the only guy shirtless. "It was horrible," says Peet. "Women would have it plastered up against the glass at the games. Fans would be yelling, 'How's your modeling career going?' "

Somewhere along the way, though, despite the dead cattle and the embarrassing photos, Peet s mad plan started to work. After Corpus, he was called up by the South Carolina Stingrays in the East Coast Hockey League, one league below the AHL. Then he moved laterally to a Georgia team located in Macon, as in "makin'," as in the team's name, the Macon Whoopee.

Over the summers he would work a variety of jobs, spending a few weeks helping to build log cabins. In the summer of 2003 he was trying out for a position as a jackman on Bill Davis' NASCAR pit crew. Coming back down to the States after one visit to Canada, Peetwas stopped by a zealous guard, defending our nation from suspicious people.

The agent asked him where he was going.

"To Macon, Georgia."

"Why?"

"To play hockey."

"In Georgia? And what's the team's name?"

"The Macon Whoopee."

The feds didn't buy it. Peet was held at the border and missed his plane while they tried to verify his story.

Peet played for the Whoopee for almost an entire season. Then, in March, he finally got the call: It was the Wilkes-Barre Penguins of the AHL.

"I was sitting in my kitchen, making lunch," says Peet. "I didn't have time to finish my lunch or even pack. I had to be at the Atlanta airport, an hour away, in an hour and a half. I put my gear in my car and hit the road."

He showed up just before the game and then, in a rare feat for Peet, scored a goal. After he put the goal in the net he stood dazed on the ice, not even celebrating The paper the next day said that the only time he looked like a rookie was when he scored. "I just couldn't believe I had been called up to the AHL and had played and had actually scored," says Peet. "I was like, 'Everything I ever wanted to do, I've just done.'"

The Penguins liked him and asked him to stick around for another game. At last he was practicing and playing with the halfmillion-dollar guys who were regularly going up to the NHL. There wasn't anything more he could have asked for, but it was all day to day. Peet was still wearing the same set of clothes he had been in when he had jumped in the car. He was starting to worry that people might notice. Finally, after about a week, the coach came up to Peet and said, "Hey, Peetie, what's your clothes situation?"

Peet was embarrassed. He figured he must have been getting kind of smelly.

"Oh, I'm washing them every other day," he said.

The coach had been wondering only if he had brought enough. The team wanted to sign him for the rest of the season. Peet went out and bought a few changes of clothes that afternoon.

The team was on a hot streak and Peet played right through the playoffs and into the finals, a best-of-seven series, which the Penguins lost, 2-4. During that season he even played the Providence Bruins at the Civic Center. 'Again," he says, "I just couldn't believe what was happening to me."

In June he got back home to Macon. He hadn't been back to his apartment the whole time, and the lunch he had been in the middle of making back in March was rotting on the counter.

Peet's time with the AHL, however, was over. There was a whole season of newer, younger prospects for the AHL to try out, and the Penguins were finished with the sleeper who had worked his way up from Texas.

Peet is still playing hockey, though. He's now in Albuquerque as captain of the New Mexico Scorpions of the Central Hockey League (a reorganized version of the WPHL), following a stop with the Greensboro Generals, where he played against Corpus Christi and other Texas teams. It's not such a bad deal. He's been a hero in every town, particularly in Corpus, where he saved a drowning 4-year-olds life, fishing him out of a pool and performing CPR, which Peet had learned in order to lead a freshman trip at Dartmouth. He's a hero in Albuquerque, too. "They make a big deal about the Dartmouth thing," says Peet. "Ivy Leaguers aren't too common in most of these places."

In Albuquerque he recently joined the prestigious Albuquerque Search and Rescue Team, a national outfit that is a first responder following major crises like the Oklahoma City bombing and September 11 attacks. The team was looking for a big guy who could carry the heavy drills. Peet jumped at the chance and is learning ropework and rappelling; soon he may start training a rescue dog.

"It's an amazing opportunity," says Peet, who plans to make the current season his last playing hockey "I always wanted to be a firefighter, too." a

"I think the guy who stitched me up wasn't actually a doctor. I think he might havebeen a or something."

Peet's Pages What's the perfect novel for a late-night bus ride across Texas en route to the next hockey arena? Here's a sampling of Shaun Peet's picks: Atlas Shrugged The Fountainhead The Red Badge of Courage The Grapes of Wrath In Cold Blood A Farewell to Arms A Tale of Two Cities The Alchemist A Prayer for Owen Meany The Cider House Rules Wuthering Heights The Iliad The Odyssey Don Quixote Oliver Twist David Copperfield The Brothers Karamazov Night and Day Sons and Lovers The Great Gatsby 1984 Animal Farm

aren't too common in most of these places," says Peet.

BRYANT URSTADT is a freelance writer. He haswritten for Harper's, The New Yorker and The New York Times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

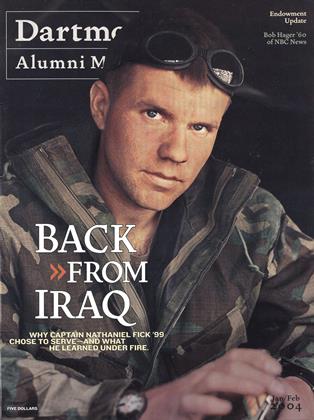

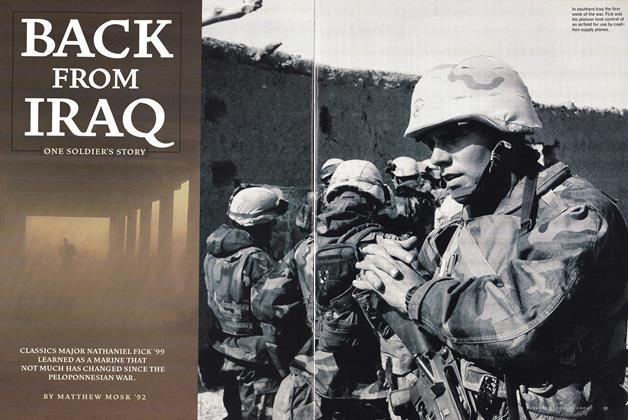

Cover StoryBack From Iraq

January | February 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureBrenda and Mindy and Matt and Ben

January | February 2004 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionDollars and Sense

January | February 2004 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleCharting a New Financial Course

January | February 2004 By Jamie Heller '89 -

Interview

Interview“Responding to Reality”

January | February 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Personal History

Personal HistoryLife In a Cubicle

January | February 2004 By Liam Kuhn ’02

Bryant Urstadt ’91

-

Sports

SportsHuge Specimen

Nov/Dec 2003 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

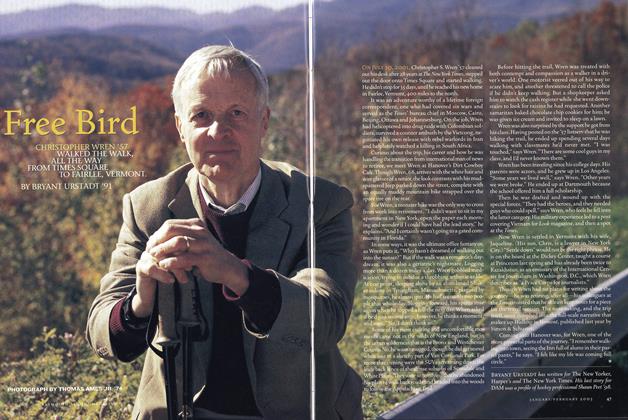

FeatureFree Bird

Jan/Feb 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryVoices Crying (and Laughing) in the Wilderness

Sept/Oct 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

OFF CAMPUS

OFF CAMPUSShrimp, Sirloin, Sass

July/August 2006 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

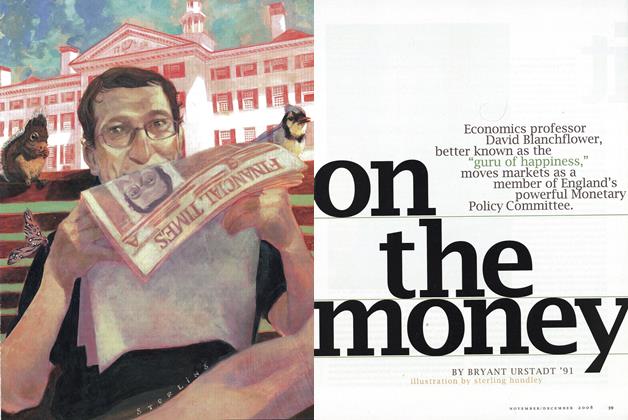

FeatureOn the Money

Nov/Dec 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

FACULTY

FACULTY“This Is Gonna Work”

Sept/Oct 2009 By Bryant Urstadt ’91

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMore Than Lived-in

April 1981 -

Feature

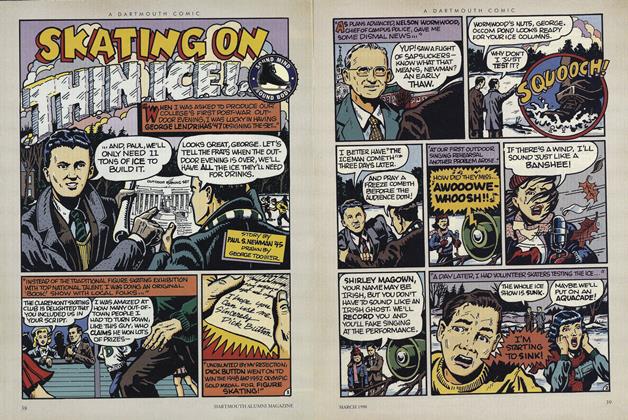

FeatureSKATING ON THIN ICE!

March 1998 -

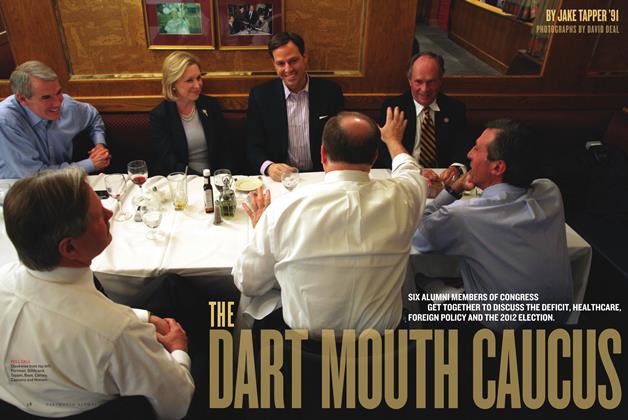

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Caucus

July/August 2011 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

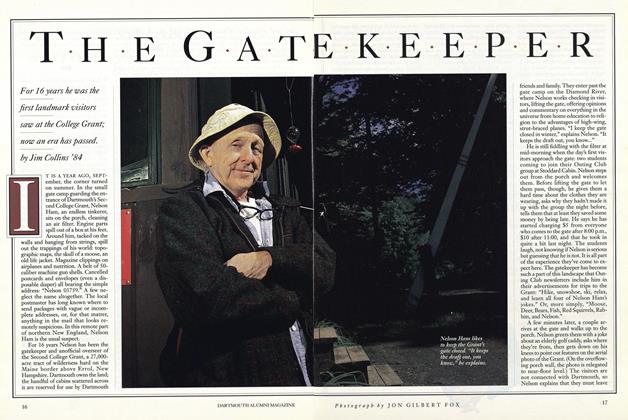

FeatureThe Gate keeper

SEPTEMBER 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTime Out

Jan/Feb 2012 By KRISTEN HINMAN ’98 -

Feature

FeatureCreativity: The Open Dance at Dartmouth

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Prof. Blanche Gelfant