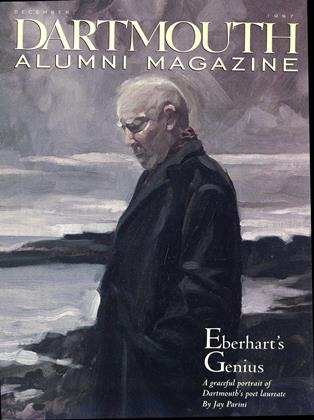

His poetry rises from an innocence earned by immersionin the hard facts of the world.

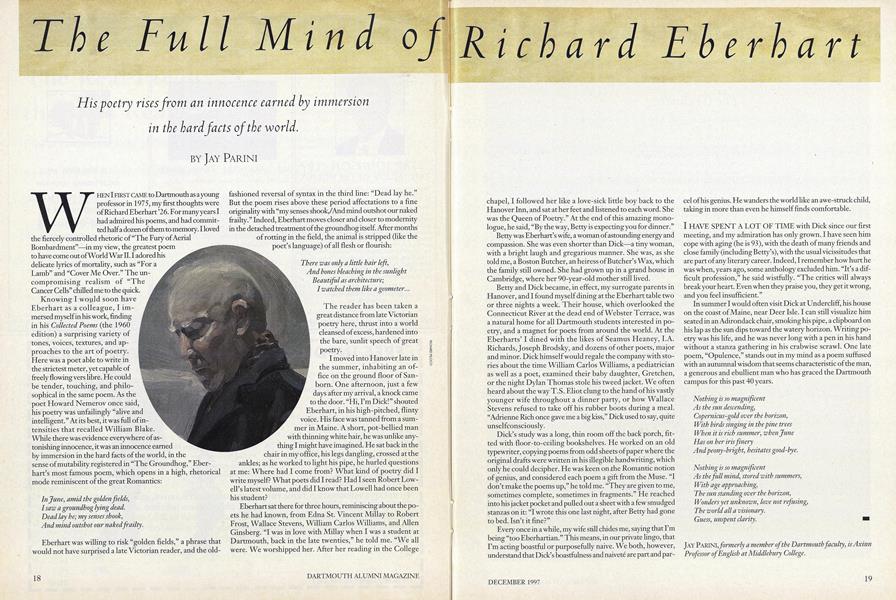

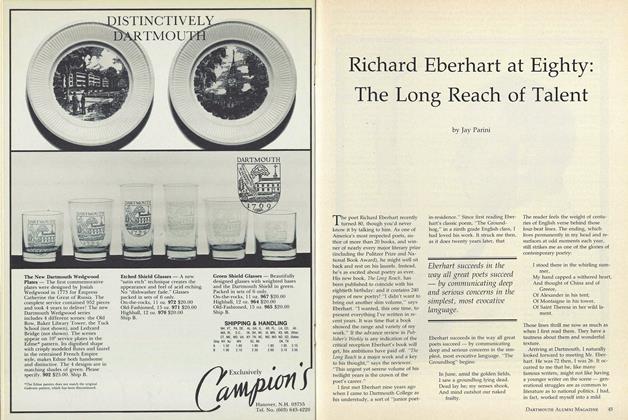

WHEN I FIRST CAME to Dartmouth as a young professor in 1975, my first thoughts were of Richard Eberhart '26. For many years I had admired his poems, and had committed half a dozen of them to memory. I loved the fiercely controlled rhetoric of "The Fury of Aerial Bombardment"—in my view, the greatest poem to have come out of World War II. I adored his delicate lyrics of mortality, such as "For a Lamb" and "Cover Me Over." The uncompromising realism of "The Cancer Cells" chilled me to the quick.

Knowing I would soon have Eberhart as a colleague, I immersed myself in his work, finding in his Collected. Voems (the 1960 edition) a surprising variety of tones, voices, textures, and approaches to the art of poetry. Here was a poet able to write in the strictest meter, yet capable of freely flowing vers libre. He could be tender, touching, and philosophical in the same poem. As the poet Howard Nemerov once said, his poetry was unfailingly "alive and intelligent." At its best, itwas full of intensities that recalled William Blake. While there was evidence everywhere of astonishing innocence, it was an innocence earned by immersion in the hard facts of the world, in the sense of mutability registered in "The Groundhog," Eberhart's most famous poem, which opens in a high, rhetorical mode reminiscent of the great Romantics:

In June, amid the golden fields,I saw a groundhog lying dead.Dead lay he; my senses shook,And mind outshot our naked frailty.

Eberhart was willing to risk "golden fields," a phrase that would not have surprised a late Victorian reader, and the old fashioned reversal of syntax in the third line: "Dead lay he." But the poem rises above these period affectations to a fine originality with "my senses shook,/And mind outshot our naked frailty." Indeed, Eberhart moves closer and closer to modernity in the detached treatment of the groundhog itself. After months of rotting in the field, the animal is stripped (like the poet's language) of all flesh or flourish:

There was only a little hair left,And bones bleaching in the sunlightBeautiful as architecture;I watched them like a geometer...

The reader has been taken a great distance from late Victorian poetry here, thrust into a world cleansed of excess, hardened into the bare, sunlit speech of great poetry.

I moved into Hanover late in the summer, inhabiting an office on the ground floor of Sanborn. One afternoon, just a few days after my arrival, a knock came to the door. "Hi, I'm Dick!" shouted Ebwrhart, in his high-pitched, flinty voice. His face was tanned from a summer in Maine. A short, pot-bellied man with thinning white hair, he was unlike anything I might have imagined. He sat back in the chair in my office, his legs dangling, crossed at the ankles; as he worked to light his pipe, he hurled questions at me: Where had I come from? What kind of poetry did I write myself? What poets did I read? Had I seen Robert Lowell's latest volume, and did I know that Lowell had once been his student?

Eberhart sat there for three hours, reminiscing about the poets he had known, from Edna St. Vincent Millay to Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, and Allen Ginsberg. "I was in love with Millay when I was a student at Dartmouth, back in the late twenties," he told me. "We all were. We worshipped her. After her reading in the College chapel, I followed her like a love-sick little boy back to the Hanover Inn, and sat at her feet and listened to each word. She was the Queen of Poetry." At the end of this amazing monologue, he said, "By the way, Betty is expecting you for dinner."

Betty and Dick became, in effect, my surrogate parents in Hanover, and I found myself dining at the Eberhart table two or three nights a week. Their house, which overlooked the Connecticut River at the dead end of Webster Terrace, was a natural home for all Dartmouth students interested in poetry, and a magnet for poets from around the world. At the Eberharts' I dined with the likes of Seamus Heaney, I.A. Richards, Joseph Brodsky, and dozens of other poets, major and minor. Dick himself would regale the company with stories about the time William Carlos Williams, a pediatrician as well as a poet, examined their baby daughter, Gretchen, or the night Dylan Thomas stole his tweed jacket. We often heard about the way T.S. Eliot clung to the hand of his vastly younger wife throughout a dinner party, or how Wallace Stevens refused to take off his rubber boots during a meal. "Adrienne Rich once gave me a big kiss," Dick used to say, quite unselfconsciously.

Dick's study was a long, thin room off the back porch, fitted with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. He worked on an old typewriter, copying poems from odd sheets of paper where the original drafts were written in his illegible handwriting, which only he could decipher. He was keen on the Romantic notion of genius, and considered each poem a gift from the Muse. "I don't make the poems up," he told me. "They are given to me, sometimes complete, sometimes in fragments." He reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out a sheet with a few smudged stanzas on it: "I wrote this one last night, after Betty had gone to bed. Isn't it fine?"

Every once in a while, my wife still chides me, saying that I'm being "too Eberhartian." This means, in our private lingo, that I'm acting boastful or purposefully naive. We both, however, understand that Dick's boastfulness and naivete are part and pareel of his genius. He wanders the world like an awe-struck child, taking in more than even he himself finds comfortable.

I HAVE SPENT A LOT OF TIME with Dick since our first meeting, and my admiration has only grown. I have seen him cope with aging (he is 93), with the death of many friends and close family (including Betty's), with the usual vicissitudes that are part of any literary career. Indeed, I remember how hurt he was when, years ago, some anthology excluded him. "It's a difficult profession," he said wistfully. "The critics will always break your heart. Even when they praise you, they get it wrong, and you feel insufficient."

In summer I would often visit Dick at Undercliff, his house on the coast of Maine, near Deer Isle. I can still visualize him seated in an Adirondack chair, smoking his pipe, a clipboard on his lap as the sun dips toward the watery horizon. Writing poetry was his life, and he was never long with a pen in his hand without a stanza gathering in his crabwise scrawl. One late poem, "Opulence," stands out in my mind as a poem suffused with an autumnal wisdom that seems characteristic of the man, a generous and ebullient man who has graced the Dartmouth campus for this past 40 years.

Nothing is so magnificentAs the sun descending,Copernicus-go Id over the horizon,With birds singing in the pine treesWhen it is rich summer, when JuneHas on her iris fineryAnd peony-bright, hesitates good-bye.

Nothing is so magnificentAs the full mind, stored with summers,With age approaching,The sun standing over the horizon,Wonders yet unknown, love not refusing,The world all a visionary.Guess, unspent clarity.

JAY PARINI, formerly a member of the Dartmouth faculty, is AxinnProfessor of English at Middlebury College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

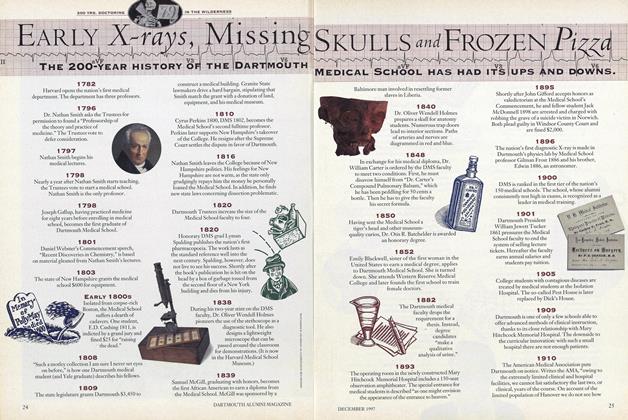

FeatureEarly X-rays, Missing Skulls and Frozen Pizza

December 1997 -

Feature

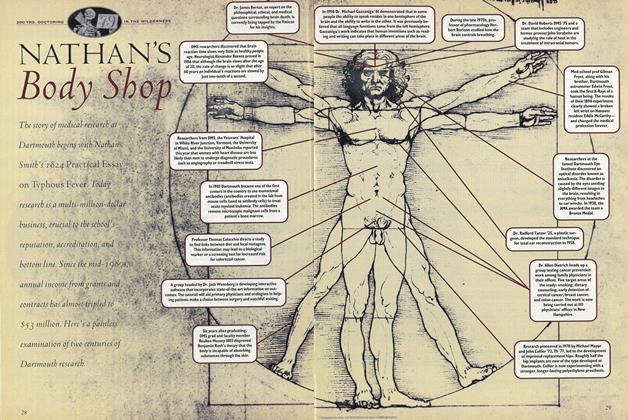

FeatureNathan's Body Shop

December 1997 -

Feature

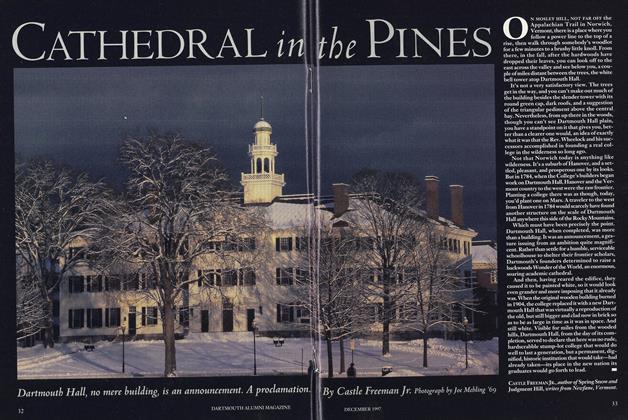

FeatureCathedral in THE PINES

December 1997 By Castle Freeman Jr. -

Feature

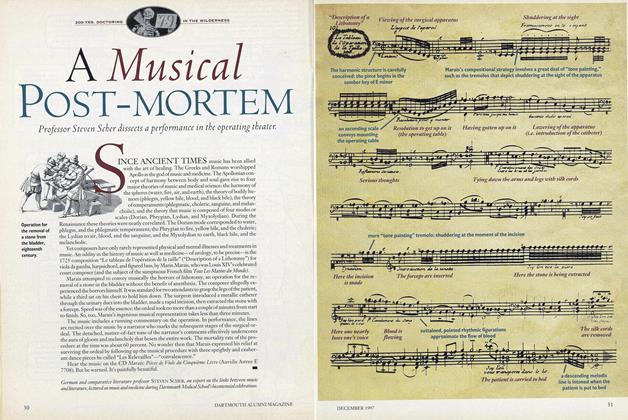

FeatureA Musical Post-Mortem

December 1997 -

Feature

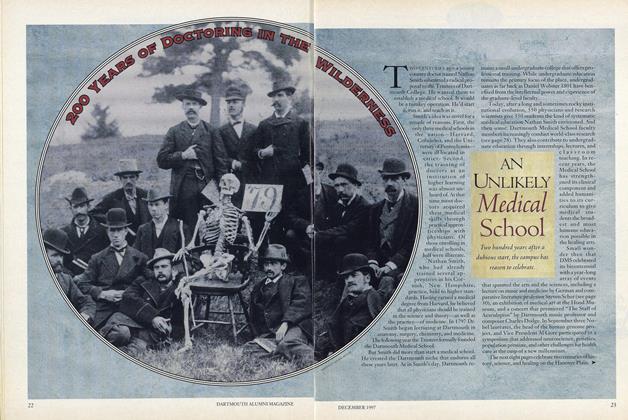

FeatureAn Uulikely Medical School

December 1997 -

Article

ArticleStars & Streep for Autumn

December 1997 By "E. Wheelock."