The following tribute to the late Gordon Ferrie Hull, Appleton Professor of Physics, Emeritus, was delivered by his colleague, Prof. Willis M. Rayton of the Physics Department, at the memorial service in Hanover on October 21, 1956.

IT is GOOD, and entirely fitting the nature of the man himself, that we friends of Professor Hull make of these moments an opportunity for reflection on his outstanding qualities as a scientist, an educator, and a man rather than for expressions of sadness and regret. There are attitudes and qualities displayed by every man in his experiences of living which are well worth contemplation by his contemporar- ies and successors. Gordon Ferrie Hull's life was uncommonly rich in such qualities.

Born in Garnet, Ontario, in 1870, he attended the University of Toronto and was graduated in 1892. After three years on the staff of that university, he proceeded to graduate work in physics at the University of Chicago and there earned in 1897 the first Ph.D. granted under the famous physicist Michelson. Following a year as Professor of Physics at Colby College, he came to Dartmouth in 1899 and became Appleton Professor of Physics in 1903. He studied abroad in 1905-06 and became a Fellow of St. John's College at Cambridge University, England. For the "crime of approaching the age of seventy," as he jokingly used to, remark, he was designated Professor Emeritus in 1940. Although officially in retirement, he taught on a part-time basis in the Navy V-12 program from the fall term of 1941 to November 1944. Thus from 1899 until 1956, Dartmouth College, the Hanover community and the world of science were uniquely enriched by the many fruits of his professional skills and personal talents.

It is characteristic of Professor Hull that his graduate studies in the University of Chicago should have had to do with the application of principles of the interferometer to the study of what were then the mysteries of so-called "electric" waves, for he was at his scientific best in applying the well-tested "classical'* methods of analysis and experiment to the elucidation of "modern" mysteries of physics. Beginning his graduate work at a time when the preeminent physicists of the day were expressing the opinion that "it now appears that all of the great fundamental principles of physics have been discovered, [and] from now on progress will lie in the seventh place of decimals," Professor Hull's initial work and indeed his whole scientific career were in complete refutation of that prophecy. It is also typical of him that his doctoral work should have centered on a topic then close to the expanding frontier of physical science. Throughout his career his active mind pushed continually outward toward the growing edge of his professional field - a field which multiplied and proliferated at a rate almost beyond belief, and certainly beyond any precedent — in the half-century which he used to call the "rush hour" of twentieth century physics. Beginning with the discovery of X-rays announced at Christmastime 1895, physics has advanced at a pace which might well have bewildered a lesser man. Far from being bewildered, Professor Hull delivered a public demonstration lecture on the subject of X-rays within two weeks of learning of their discovery, while he was still a graduate student, and he was publishing a textbook on Modern Physics at the age of 77!

This sheer delight with which he welcomed and probed the new and unexpected never left him. It carried him and Professor Nichols through the delicate

and exacting experiments for which their names are internationally honored when they measured the infinitesimal pressure exerted by a beam of light. With unmatched precision this work, carried on here in 1901, brought the first experimental proof of the detailed validity of the electromagnetic theory of light - certainly the greatest contribution of the greatest theoretical physicist of the 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell. The results of the Nichols and Hull experiments, with their applications to astrophysics and their broad implications for the field of physics generally, are such that the names of these experimenters will be long remembered.

The American Physical Society, formed in 1899, at its meeting in December 1902 heard four papers presented which turned out to be of historical greatness. Those papers dealt with the pressure of light, the identification of the alpha particles coming from radioactive matter, and the properties of the penetrating radiation later known as "cosmic rays." Professor Hull gave the paper on light pressure. In January 1953 the Secretary of the Society invited Professor Hull, after fifty years of distinguished membership, to give a paper entitled "Fifty Years of Light Pressure" at the annual meeting. Changing to the larger title of "Experimental Discoveries Announced at the Meeting of this Society Fifty Years Ago," Professor Hull, at the age of 83, delivered the address before a capacity audience in the Sanders Memorial Theater at Harvard University in a way that made all Dartmouth proud of its association with him. He thus became the only person in the history of the Physical Society to appear as a speaker on two occasions fifty years apart. In writing later to his friend Waldemar Kaempffert, science editor of The New YorkTimes, Professor Hull commented, with characteristic perspective and humor, "I am the only one now living who presented papers at the 1901 and 1902 meetings of the Physical Society. The present Secretary is unfortunately limited in his choice of speakers!"

Following completion of the light-pressure researches, Professor Hull turned his energies strongly into the work of teaching physics, not only to the undergraduates of Dartmouth, but to local schoolboys, to his graduate assistants, and to the townspeople of Hanover as well. In the classroom, in his laboratory, in the weekly Physics Department Colloquium which began with tea in his office some 55 years ago, and in public lectures, he has given to all who approached with sincerity of purpose, a measure of his contagious enthusiasm and curiosity regarding the latest riddles in physics. Young men who were his laboratory and lecture-room assistants have gone on to distinguished careers at universities such as Columbia, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, and M.I.T. At Pomona College, Roland R. Tileston '07 achieved national honors for his notable contribution to the teaching of physics, since from his classes alone thirty went on to obtain the Master's degree, and 24 others continued for the Ph.D. degree. Others of Professor Hull's men have achieved their greatest success in research, most notably M. Stanley Livingston, coworker with Dr. Lawrence at Berkeley in building the first cyclotron and later de signer and builder of several of the enormous machines used today for the acceleration of the assorted projectiles essential to research in nuclear physics. Another youth, doing very ordinary work in a very ordinary machine shop, in 1909 walked up from White River Junction to attend some of Professor Hull's evening lectures. Recognizing a keen mind and evidence of some mechanical skill, Professor Hull made him his assistant, thus giving him the opportunity of becoming acquainted with physics and with certain precision methods of physics. David Mann became a recognized master in applying those methods to the manufacture of scientific apparatus and is even yet called into consultation on such matters. Men like these, and many others of the Dartmouth family who never went beyond Professor Hull s Physics 3-4, pay tribute to the insight, the friendship, the practical help, and the inspiration which they received in their association with this man of keen perceptiveness and wide-ranging mind.

During World War I, and for some time after, Professor Hull served as Major in the Ordnance Department of the Army, where with Dr. Lyman Briggs, long-time Director of the National Bureau of Standards, he conducted experiments on the streamlining of projectiles. Their results are being found applicable today to some of the problems of flight at supersonic speeds. As a consequence of these research activities and his lively interest in the latest results of other physicists, he engaged throughout his lifetime in spirited correspondence with leading scientists around the world. And in spite of an intense concern with the arts of teaching, he somehow managed to find the time and energy to write more than a score of articles, and prepare two editions of his textbook titled An Elementary Survey ofModern Physics.

But in Hanover it will be as Professor Hull the man, rather than as noted scientist and educator, that his name and memory will live on. Although well-known for his independence of mind and forthrightness of expression when in the classroom or engaged in serious discussion, this gave way to a charmingly light-touched and whimsical manner when engaged in his other interests such as tennis, figure-skating, gardening, and people. Deeply concerned with all the activities of young people, he was a benefactor of all age groups, from grade school to Dartmouth undergraduate. He founded the Dartmouth Radio Club and imbued it with a uniquely serious purpose. He was closely identified with the very inception of the

Dartmouth Outing Club, being among those present at the preliminary meeting in December 1909 and serving as an ardent and enthusiastic member of the Faculty Advisory Committee to the group during its early years. Fred Harris '11 writes that "the support of Professor Hull and others of the faculty was an inspiration to the undergraduates and a major factor in the success of the Club from the very start."

Nature, with all the mysteries surrounding its operations, constantly beckoned him to attempt to understand. Yet he found its beauty and its immeasurable majesty a continuing reminder of his Maker. It was impossible to know Professor Hull for long or to be in one of his courses without discovering that he was a deeply religious man. Characteristically impatient with anything which he considered vaguely reasoned or poorly expressed, he was not in sympathy with some Of the forms and expressions of conventional religion. President Tucker came close to personifying for him his type of religious conviction, and it is perhaps for this reason that the deliberations of the Tucker Foundation recently established to bring new religious perspective and relevancy to our campus — were of especial interest to him.

I shall close with a paragraph from a letter written by Professor Hull in 1955 to an alumnus of the Class of 1913. Astonishing as it is as a further example of his prodigious memory, it is more significant as an expression of his religious belief. The quotation follows: "ft was very gracious and generous of you to refer to my chapel talk of 191 a. But it is amazing that you should have remembered any of it all these years. My memory regarding the points I emphasized is rather different from yours. I wanted to enlarge upon the idea of reverence. Indeed, I might have quoted at length the remarkable poem and hymn by Oliver Wendell Holmes

Lord of all being, throned afar Thy glory flames from sun and star; Center and soul of every sphere Yet to each loving heart how near."

Professor Hull then adds, "I could go on, as it is all wonderful." Following that suggestion, let us here add with him, the final verse

Grant us thy truth to make us free, And kindling hearts that burn for thee; 'Til all thy living altars claim One holy light, one heavenly flame 1

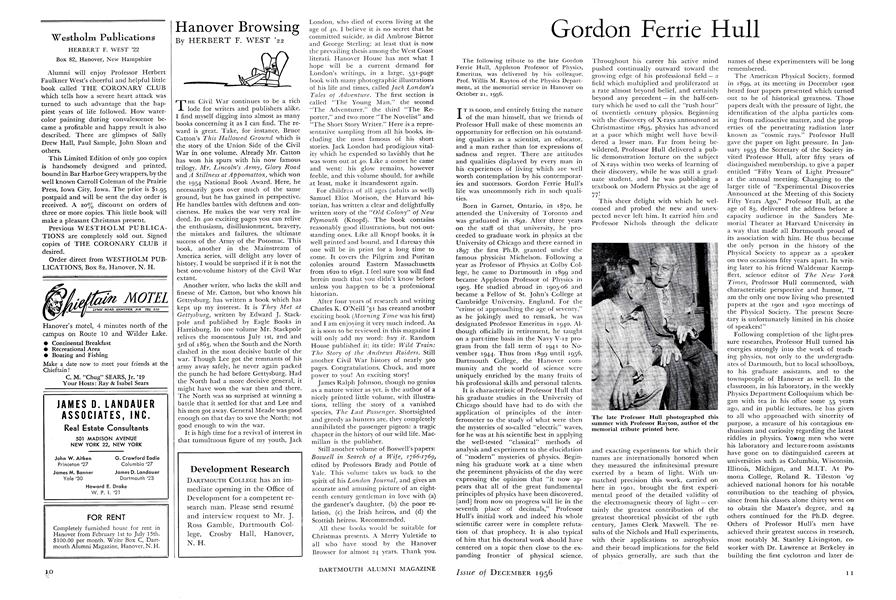

The late Professor Hull photographed thissummer with Professor Rayton, author of thememorial tribute printed here.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

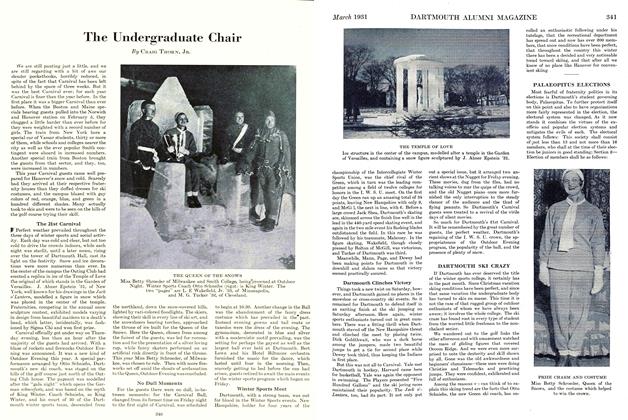

FeatureGOTHAM GAMBIT:

December 1956 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Feature

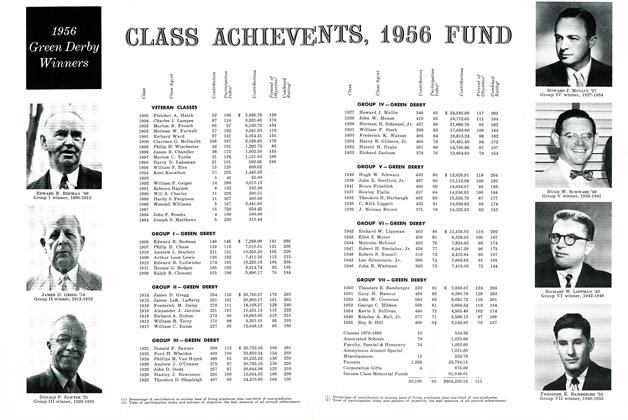

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVENTS, 1956 FUND

December 1956 -

Feature

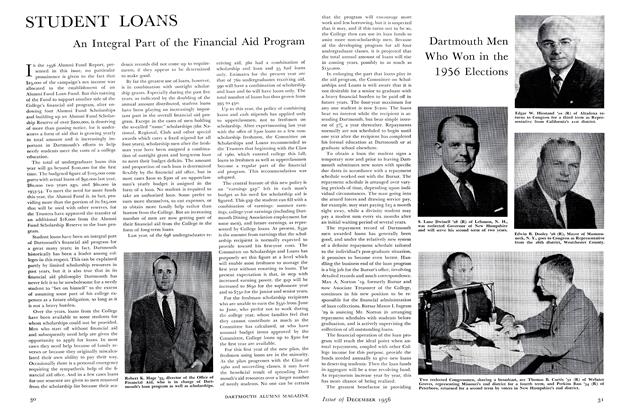

FeatureSTUDENT LOANS

December 1956 -

Feature

FeatureTHE 1956 ALUMNI FUND

December 1956 By William G. Morton '28 -

Feature

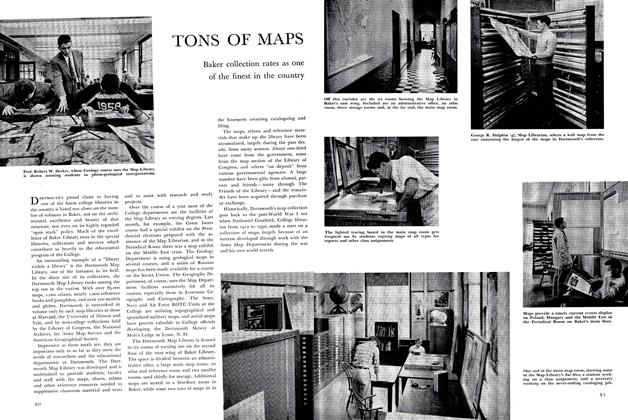

FeatureTONS OF MAPS

December 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

December 1956 By RICHARD C. CAHN, LT. (JG) EDWARD F. BOYLE, RICHARD CALKINS