A summation and a look to the future as the second Eisenhower term begins

WHITE HOUSE CORRESPONDENT FOR TIME MAGAZINE

IF Dwight Eisenhower was of a deeply reflective turn of mind, which he is not, this is the precise moment in history when he would seek a tallying of the score as to the accomplishments of his Presidency to date, his present stance, and the outlook for the tomorrow which he now faces. For at this moment, as he takes his Presidential oath of office for a second term, Dwight Eisenhower encounters politically what is in fact both an end of the beginning and the beginning of the end. Definitive history must be left to time and the scholar. But a journalist writing for today may be pardoned if he risks a summation and a future glance without the scholar's perspective of time and before the full facts are in.

Few Presidents in the nation's history, and none since the Franklin Roosevelt of 1936, holds such a mandate from his countrymen as does Mr. Eisenhower, a personally modest man who occasionally expresses unfeigned surprise that people in over-whelming numbers grant him their trust through their votes. The enormity of the President's very personal victory in November, and it is nothing if not a highly personal triumph, seems to me to be the very central fact of both the power and the weakness of his position.

For the President, without calculation or guile, has become to an overwhelming majority of Americans, a father-like figure far above his own political party and even his immediate associates in the government. This holds true not only in his own country, but extends to the far reaches of the anti-communist alliance and even to the nervous, neutralist areas of the world as well. It is a highly personal business, this love affair of the President and the people. In thousands of miles of campaign travel this fall, for example, I found few indeed who voted for the President on a basis of his "partnership policy" in developing the natural resources of the nation, or his curtailment of federal expenditures and balanced budget, or his conduct of specific foreign affairs. Rather, it seemed that Americans felt at home with "Ike." He had not only their affection, but their confidence. He somehow struck a responsive chord in the heartstrings of America.

Ironically, even in areas where he was most reticent politically, his gains were huge. For example, he broke wide open the heretofore solidly Democratic blocks of big city Negro voters though he withheld repeatedly any personal endorsement of the Supreme Court's school desegregation decision and was exceedingly mild toward marshaling federal enforcement of it. It was not specifics in the vast realm of public affairs which lodged Dwight Eisenhower at his present pinnacle of personal popularity. Rather, it was almost certainly a mutual self identification between President and constituency, and constituency with the President. The campaign traveler cannot forget the exultant cries of "OH, he waved at ME," heard constantly as the President's motorcade rolled through city streets and along country highways. Nor can one forget the President's own explanation of his occasional campaign hoarseness - "They shout at me and I just can't help shouting back."

There is no pat or easy explanation tor this fact which falls in part into the realm of the social psychologist. But it is the most predominant reality which marks the President and his relation to the people as he begins his second term. In part at least, it seems likely that the American ideal, though certainly only for the moment, is one of calm, ease, and repose after a quarter century of breath-taking adventures moved by depression and war. An America experiencing generally a remarkable degree of economic prosperity (despite some ominous inflationary signs) and shuddering at the somber risks always involved in daring unilateral leadership in foreign affairs, seemingly wants a period in which to catch its breath, conserve its gains, and to enjoy the fleeting present without change and strife. It can be argued honestly if such a stand-pat philosophy toward affairs at home and abroad is sufficient to cope with the problems involved. But I believe it beyond argument that such a public philosophy does exist. For such an epoch, be it brief or long, Dwight Eisenhower fits the country's needs. For his critics, unlike those of many American Presidents, charge him essentially with doing too little, never with attempting too much.

WHAT manner of man is the gentleman who now begins his second term? At 66 years of age, Mr. Eisenhower appears physically fit despite his two serious illnesses of the past year, and well able to withstand the fearful strains of his office, the most arduous one in the world. This is written from just off the edge of the golf course in Georgia where the President is vacationing. The crisp, clear air and the pleasures of his favorite sport have etched out the lines of strain from Mr. Eisenhower's face. His color is healthfully ruddy. He is most alert and methodical as he attends to essential work (a President really never leaves his desk, it inexorably follows him). Even now in the temporary White House communications room just below me, the teletype machines connecting the President with Washington are beating out a steady staccato of dispatches which will require his attention in his tiny office atop the golf professional's shop at the Augusta National Golf Club. The President's weight at 172 pounds is most satisfactory to his physicians. He gains zest from his exercise, not weariness. His temperament is cheerful and buoyant, occasionally cracked by a brief and transient thunderclap of anger. His dress is meticulous, leaning more and more to the warm browns rather than the grays which he once favored. His appetite is sturdy (steaks remain his favorite food, occasionally preceded by a pre-dinner Scotch highball). He sleeps soundly for at least eight hours a night and not even in the recent troublesome days of the Middle East crisis did he require a sedative. His interests are intense and directed to the practical rather than the abstract. Currently he is engrossed in a study of animal diseases and of the productivity of the Aberdeen Angus cattle on his Gettysburg farm.

Within himself, the President as he begins another term is confidently at ease. He has learned over the past four years in the White House, according to his personal friends, that quite often in the political field one cannot make military-like, sharp yes or no decisions based solely on obvious merit. A certain patience, a willingness to compromise in the interests of obtaining wider agreement, a broader tolerance of opposing viewpoints has developed in the President's makeup. The President still prefers that opinions and recommendations from his subordinates come to his desk in succinct, one-page written form and with dissents worked out before this stage in the governmental machinery is reached. He absorbs the written word almost photographically and his questioning in oral conversation is pointed, always purposeful. The President is not a philosophical man. He is pragmatic in his thinking, preferring to talk of a specific matter at hand only within the framework of that matter, not as something involving a larger, more abstract field.

His touch now is more confident than four years ago in matters of domestic policy, such as economics, social welfare, government administration, natural resources and public works. His knowledge in this field has grown measurably; it was skimpy indeed when he came to the White House. Once bored and a bit disdainful of politics with a small "P," he now is fascinated by the minutiae of winning votes and by the details of political organization, even at the ward and township level. He enjoys talking politics with Republican Chairman Leonard Hall. Yet, ironically, despite the recent campaign he remains virtually above politics in the public eye and the warmest applause during his campaign speeches came in his derogatory, somewhat sarcastic references to mere "politicians" and their talk.

MR. Eisenhower's keenest and most constant interest as he begins another term lies in the broader aspects of foreign policy, the major questions which impinge so closely on peace or war. By necessity, during the recent illness of Secretary Dulles, the President acted for the first time as his own Secretary of State and his own Chief Diplomatic Agent; and this during the dual crises of Egypt and Hungary. It is utterly likely that never again will the President relax his grip on the day-to-day functioning of American policy abroad, regardless of Secretary Dulles' potential for future service. For above all, the President's ambition is to have his second administration remembered as one in which substantial steps were taken toward effective atomic disarmament and lasting peace. Though debate can (and certainly in a democracy should) be constant and critical on the steps taken by the Eisenhower Administration toward these twin goals, no one in even casual contact with the President can doubt his sincerity or determination in this area.

And precisely here, two turning points, for better or for worse, can be noted; turning points which occurred almost simultaneously with the end of one term and the beginning of another.

The President has relaxed the exercise of the tremendous potential and actual power of the United States for world leadership in favor of a far more tentative, more delicate, more cautious approach. One need only contrast his reaction to the power play of Col. Nasser in seizing the Suez Canal and the counterthrust of the British and French with, for instance, the immediate and definitive action of former President Truman when Greece and Turkey (along with important Western interests therein) were threatened in 1946. President Eisenhower seeks to internationalize responsibility through the United Nations, with the UN taking the lead and sometimes actually determining United States responses. This contrasts sharply with action in prior years (the U.S. response to the communist invasion of the Republic of Korea, for instance), when the United Nations was turned to by the United States after the American counteraction already had been undertaken and asked merely to approve or underwrite an already established American policy. To state the case is not to agree upon the Tightness or wrongness of the new approach. What is sacrificed in American leadership may be regained in closer understanding and respect on the part of the neutral nations in Asia and Africa, something which only time will tell.

The second turning point, or new departure, as I see it at the moment Mr. Eisenhower's second term begins, is a weakening of this nation's ties with its Western allies, particularly Britain and France. Despite the President's protestations that the Grand Alliance of the West stands essential to United States foreign policy and that current points of friction will be resolved, it seems likely that the second Eisenhower term will be marked by a loosening of the ties, rather than greater support from this country for the Western allies, and by more remote rather than more intimate association. This seems apparent as interest and progress in NATO as a military shield flags, as a Western oriented military program in West Germany becomes more remote, and as United States policy in the Middle East and Asia diverges in increasing degree from that of it allies. No effort is made herein to determine which side of the Atlantic bears the major responsibility for this development or to assess the Tightness or wrongness of this course. But the trends cannot be ignored, and I think they will persist in the second Eisenhower Administration.

IN affairs at home, the President is blessed with a closely knit personal team at the White House and Cabinet level which possesses tremendous dedication to the Chief Executive and which with much effectiveness has carried forward his policies. The Cabinet and the President's own personal staff have been marked not only by these qualities, but by a beneficial continuity of service which has set some kind of modern record. There have been only three Cabinet changes since January 1953, There will be no wholesale reshuffling in the second Eisenhower Administration's high command posts and the few shifts now in sight will be dictated by reason of personal or family health, or just old-fash-ioned "Potomac weariness."

In this connection, Dartmouth College has reason to be exceptionally proud. There is no man more deserving and less seeking of credit for the Eisenhower Administration's record of accomplishment than Dartmouth's own Sherman Adams. Mr. Adams has set a new high in self-sacri-fice, efficiency and labor, in integrity and self-effacement - qualities not always markedly present on the Washington scene. With it all he has brought the salt-and-pepper flavor of New England reality to the Administration. Not only Mr. Eisenhower, but the nation as well, is extremely fortunate that Sherman Adams came down from the North Country as The Assistant to the President of the United States. (Not at all incidentally, Paul Sample's painting of the Dartmouth Campus, a gift of the College Trustees, now hangs proudly above the mantel in his White House office.)

The President, however, faces a strange and to him disturbing internal political paradox as he starts his second term. It lies in the fact that despite his own landslide, personal victory, his party in the same election was rudely rebuffed. For the first time since 1848, a President of one political party was elected on the very day that a Senate and House controlled by the party of his political opposition was chosen. Compounding the paradox, three men running for the Senate with the highest credentials as Republicans of the Eisenhower mold were defeated: former Interior Secretary Douglas McKay, James H. Duff, one of the men originally responsible for the President's entry into Republican politics, and Arthur Langlie, the President's personal choice for the Senate race in the State of Washington.

It seems apparent that the effort to sell the country on a new doctrine of Eisenhower Republicanism, or "New Republicanism," as the party's new philosopher, Arthur Larson, puts it, failed. There is evidence that this development, so strange in the light of the enormity of Mr. Eisenhower's personal triumph, is a source of considerable concern to the President himself. Repeatedly, he has stated his own belief that under the American political system a political party can best be held truly responsible for its stewardship of government if it holds simultaneous control of both the White House and the Congress. As Mr. Eisenhower put it immediately after his re-election, there was a failure in convincing the country that there actually is a doctrine of "New Republicanism," pointing up the fact that "some change in the understanding that the public has of the Republican party is necessary."

This poses directly the chief problem of domestic politics which the President faces in his second term. His often repeated aim in this field is to establish the Republican party as the majority party in the nation. The task ahead then is to convice the country that firstly there is a new Republican doctrine, quite different from the Republican dogma of bygone years, and secondly that the "new" doctrine is worthy, in its content and in the men who claim to represent it, of the nation's support.

ASSUMING the validity of the argument that there actually is a "New Republicanism," representing a cohesive doctrine differing markedly from "Present Democratism," the President faces a most formidable task in undertaking to win popular support for it. This will be a major Eisenhower effort in the new term.

Firstly, Mr. Eisenhower will be hobbled by the fact that under law this is his final term in office; incidentally a law written by his own party largely through spite and bitterness toward the late Franklin Roosevelt and which now in its first application pertains not to a Democratic President, but to an immensely popular Republican President. (It expressly exempted former President Truman since it was written into the Constitution during the Truman incumbency.) Mr. Eisenhower has given evidence that he considers the two-term limitation an unfortunate encumbrance and a slur upon the judgment of the American electorate. It is known that he regards it as particularly hurtful in weakening a secondterm President, especially during his last two years, in conducting foreign relations with nations well aware that soon they will deal with a new President with new policies of his own. Mr. Eisenhower either hopes or believes, it is not quite clear which, that this debilitating effect can be lessened at home in the supremely important matter of gaining congressional support from his own political party for his legislative program. He sees as a weapon now available to him the desire of potential Republican Presidential candidates to be assured of his support for their own ambitions. There seems a likelihood that this is too sanguine a hope.

The transferability of personal popularity, even Dwight Eisenhower's, to others seems a discredited political illusion, particularly as the results of the November election are studied. That is precisely what Mr. Eisenhower was unable to do for many Republican candidates running on his coattails for the Congress. And with a half-dozen potential Republican Presidential candidates already in the wings, more, rather than less, pulling and hauling within Republican ranks seems inevitable. No doubt it will begin on just about the day Congress convenes this month and increase in intensity as the months of the second Eisenhower Administration melt away.

Adding to the difficulties confronting the second-term President in enacting his program is the fact that the reports of the demise of the Democratic party not only were premature, but were quite untrue. Even the President has had to backwater sharply from his election night victory statement that the election represented a sweeping party victory for the "New Republicanism." With a vacuum present in the Democratic party so far as a 1960 nominee is concerned, and with consequent violent Democratic jockeying for position, the outlook for support of an Eisenhower congressional program from this quarter seems quite remote. In fact, the considerable degree of cooperation from "moderate" Democratic congressional leadership, received during the first Eisenhower term, now seems far less likely.

Thus, abroad and at home, Dwight Eisenhower as he takes his oath of office for a second term, is beset by most vexing problems, large and small. The great and consuming question is the degree to which this American President, so immensely popular with his countrymen, can use precisely that popularity in exercising successfully his leadership at home and abroad. The stakes far transcend his personal ambitions and his own political party. Indeed they extend far beyond the welfare of the nation, to that of the whole free world.

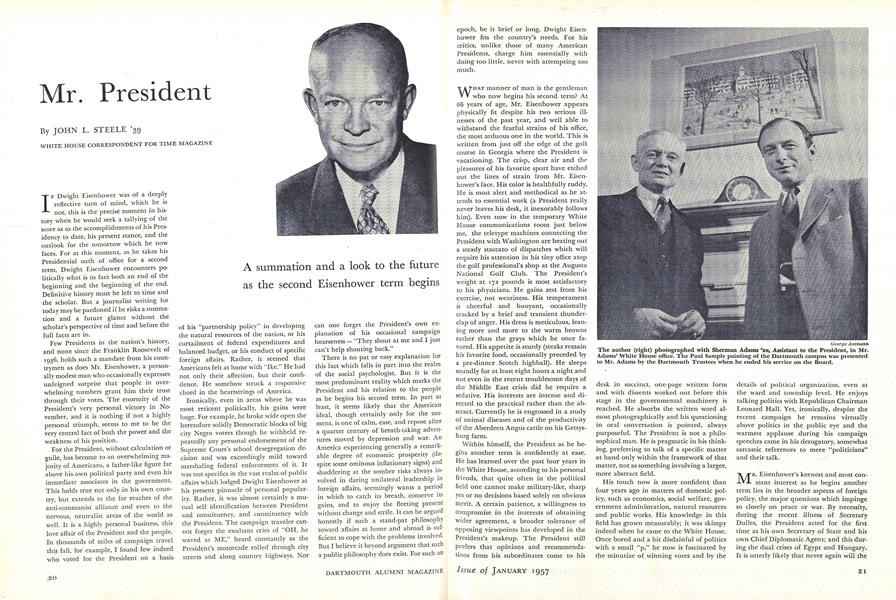

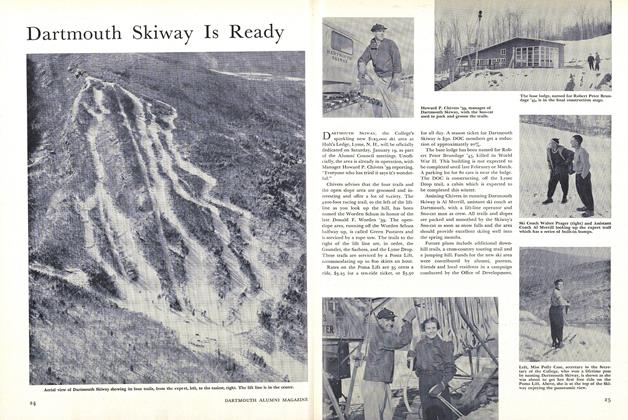

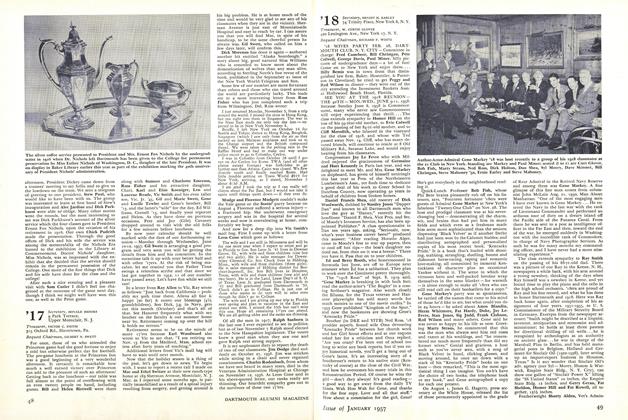

George Assmann The author (right) photographed with Sherman Adams '20, Assistant to the President, in Mr. Adams' White House office. The Paul Sample painting of the Dartmouth campus was presented to Mr. Adams by the Dartmouth Trustees when he ended his service on the Board.

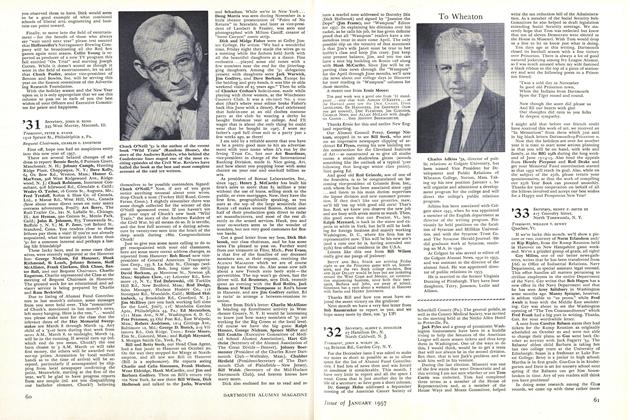

President Eisenhower with President Dickey at the Dartmouth College Grant in 1955

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhy Teachers Teach

January 1957 By ANDREW G. TRUXAL, -

Feature

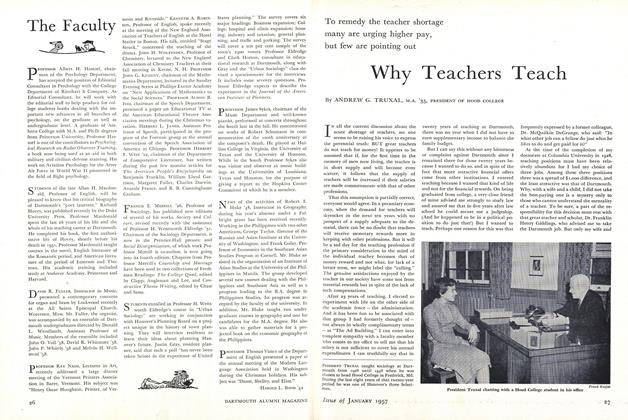

FeatureDartmouth Skiway Is Ready

January 1957 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

January 1957 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

January 1957 By JOHN H. RENO, PETER B. EVANS, CHARLES G. ENGSTROM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

January 1957 By RICHARD C. CAHN, LT. (JG) EDWARD F. BOYLE, RICHARD CALKINS

JOHN L. STEELE '39

Features

-

Feature

FeatureGeorge Nickum '31 to Head Alumni Council for 1956-57

July 1956 -

Feature

FeatureREUNION WEEK

JULY 1973 -

Feature

FeatureCarnival Post-Mortem

March 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

APRIL 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureAll the Presidents's People

SEPTEMBER 1981 By J. N. -

Feature

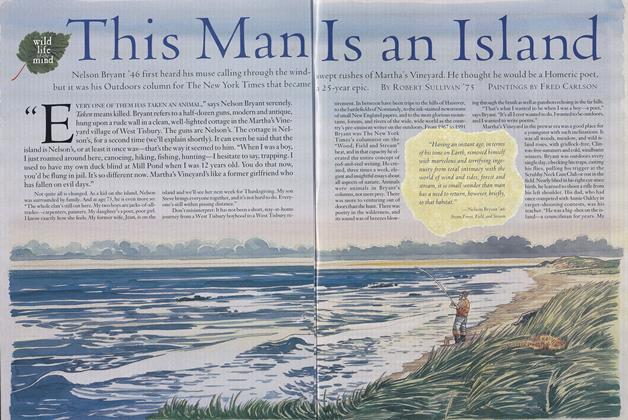

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

OCTOBER 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75