CHAIRMAN FORMER U.S. AMBASSADOR TO GREAT BRITAIN

I HAVE asked myself the question: Why should person a living in Binscarth, Manitoba, in the middle of the great Canary prairies of the North American continent have any concern about events and incidents, developments, beyond the shores of the Atlantic on the one side, the Pacific on the other? Why should he have any interest in the relations between Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom? And I've asked myself the question: Why should a family living in Keokuk, lowa, deep in the heart of a massive continent, have any anxiety about what may occur in the Pacific, or far out in the waters of the Atlantic, or north of 54-40 or fight? And why should a mechanic living in Birmingham be aware of the personal consequences to himself of the role of history beyond the shores of his island?

That there is, of course, a common philosophical inheritance - that there is a political heritage of institutions common to us all, though these institutions similar in substance may be so different in form as to cause irritations if not prejudices - that there is this common language which so far has not been too much of an impediment to understanding - these are not good enough reasons, valid though they are, for any deep-seated concern about achieving unity among us. If they are not by themselves good enough reasons for hammering out some sort of a definition of common purposes, if not of common methods, it is fair to say that without this common philosophical and moral foundation any other accord on purposes and methods would be far more brittle, far more fragile, and far more transient.

I would like to address myself to some of the other reasons which, associated with the moral, the political and the philosophical ones, should compel us to try to achieve some sort of unity of purpose and of method.

During the course of the last twelve years to fifteen years we have observed a migration of the seats of power to the eastward and to the westward, a migration of power expressed in absolute and relative terms which, perhaps, has never before been known on this scale in modern history. Perhaps I should remind you of that acute observation which Professor Butterfield made in his lectures called "Christianity in History," when he observed that men have a habit - I cannot quote him exactly - of continuing to live as though they were in a world of their making, that the past is still with them, that they are unacquainted with the changes that have occurred, and that they go on weaving the pattern of their lives as though what had been, but had long since in fact disappeared, still actually was. This, I sometimes think, is an error which we all commit, and I think, therefore, it is important to place great emphasis upon the organic and structural changes that have taken place in the course of the last fifteen years, if we are to understand why, why, it is important to attempt to achieve some sort of accommodation between this strange, powerful, important and significant triangulation of nation states. And one of them, to repeat, is that never in modern history has there been such a migration of the seats of power as the migration we have witnessed during the course of the last twelve to fifteen years.

The second consideration, and consideration of great weight, is that the waters which intervened to divide and the vast frozen stretches of the North which existed to protect are no longer barriers.

The third consideration is that through the application of scientific knowledge man has been able to project vehicles in three dimensions high over the lands of the world and high over the seas at supersonic speed.

And the fourth consideration is that by the application of scientific knowledge man for better or for worse has developed a lethal weapon, a series of lethal weapons, the full consequences of which nobody yet fully comprehends, which present a rather awesome prospect for the future, and which remind us of the famous question with which Lowell ended an article in Foreign Affairs: "Is the ultimate gift of the natural sciences to man universal destruction?"

Now, because some mistake in judgment made on the periphery of what we call the Western World might precipitate us into another great convulsion, it is important, indeed it may be a matter not only of defense but even of survival, that we hammer out some sort of a permanent definition of purpose and as nearly as possible a common application of methods in this triangular community, which is such an important segment of the Commonwealth and of the Western World. And it is because each one, each member of this triangular community, is deeply affected by the monetary, financial and economic developments that occur not only within the borders of each but beyond the borders of each that the family that lives in Binscarth, Manitoba, or Keokuk, lowa, or Birmingham, England has a deep concern and is seriously affected by external as well as internal behavior. These are the basic reasons which bind this community together, and which compel us to be driven, if we only will be driven, into reaching some sort of an accord. . . .

Now it is not my purpose, nor is it my responsibility, to trespass upon the domain of the respective panelists. They will define issues, they will ventilate them by discussion; but there are three or four to which I would like to make reference very briefly, in the hope that they may perhaps inspire the panelists to elaborate upon them and to deal with them as perhaps they ought to be dealt with. Frankness and candor, even to the extent of producing embarrassment at times, are important to a clear expose of the obvious, the obscure, and the subtle factors which weigh with all of us in the discussion of each one of these issues. The most that we can hope for is an accord about purposes and methods; the least that we can expect is a complete understanding, for without understanding we might well break upon the rocks of discord.

The relations between Canada and the United States have gone through cyclical periods Now, although the relations are still warm and friendly, a number of developments have occurred increasingly over the last decade which have given rise to some apprehension. This unfettered movement of capital - and so capital should be, unfettered - into Canada for the development of Canadian natural resources, without offering our good Canadian friends the opportunity to participate, has engendered a manifestation of apprehension lest the richness of this great country to the north of us be developed for the benefit of those who have imported the capital, without adequate compensation or benefit to the citizens and the commonwealth of Canada. This is not altogether a captious point of view; there is some merit to it. And similarly, there has developed in Canada, because the trade union movement there is so intimately associated with the trade union movement in the United States, and because the demands of the trade union leaders in Canada are similar to the demands of the trade union leaders in the United States, an apprehension that from this country an attempt is being made to impose upon Canada a standard which Canada, perhaps, might not be otherwise willing or prepared to accept, or even able to carry. '

Then there are issues of a competitive nature, centering perhaps more principally upon the great grain growing parts of both countries. I remember Sir Wilfrid Laurier making a speech in London a good many years ago when he went over some of these issues between Canada and the United States and referred to the rather jealous eyes with which Americans on occasion look north of the border, and made the observation that this was really a compliment to Canada on the one hand and an acknowledgment of the sense of discrimination of the Americans for, he said, the Americans know a good thing when they see it. And so we do.

These are some of the issues that I would hope at one stage or another the panels would come to grips with.

As between Canada and the United Kingdom there is a strange sort of contradiction. Canada with great loyalty, faithfulness, affection and pride accepts the Crown to be her own as much as do the people of the United Kingdom, and yet at the same time the Canadian dollar is a part of the dollar area, the Canadian currency is not a part of the sterling area. This is a function of the intimate economic relations between Canada and the Western hemisphere. There are many occasions when Canada has exercised an independent role in the definition of her own foreign policy, and these occasions have given rise to certain abrasions in the vicinity of Whitehall.

And as between the United States and the United Kingdom there are a variety of different, prickly, and perplexing problems. Let us, for example, deal with the question of colonialism. Many persons in Keokuk, lowa, partly as a residual consequence of the bad teaching of American history, and persons in other sections of this massive continent think of the United Kingdom of Britain, the English, as a colonial power intent upon preserving by force and tyranny the system of exploitation of distant peoples for their own benefit. And for many years, too many, we have directly or indirectly been advocating the dissolution of colonial ties and the liberation of subjugated peoples. The former has given rise to prejudice against our own best ally, and the latter has caused strong resentments in London, Edinburgh, Birmingham, and Ottawa. I only hope that the panel will dissect this issue, will reveal it for what it is. . . .

May I talk of another one - investment, commercial policy and foreign aid of the United States? Can the investments that have been made, the loans that already exist, be serviced properly and fully without a modification of our own commercial policy on a sufficiently large scale or without foreign aid, or both? If we are unwilling to modify our commercial policy,' are we not compelled to accept either a shattered and tattered international monetary and financial system or, which is not to our national interest or to yours, continued foreign aid as a subsidy to those who have made investments and an extension of the subsidization of the vested interests that resist any modification of commercial policy at home? Now here are some questions that bear with great violence upon the achievement of some sort of an orderly international monetary and financial system, as important to Canada and the United States as it is to the United Kingdom. Does the experience which we enjoyed during the twenties throw any light upon this problem? And associated with it, is the question of convertibility of foreign currency. Can this matter be advanced to the benefit of the whole of the Western world?

And then there is the matter of Britain's relationship to the common market. What may be the consequences to the North American continent if this common market develops into one that is common unto itself but protected against all other markets?

And there are still the residual hurt feelings arising out of the unfortunate events of last fall. We have the problem of Syria with which perhaps we may not have to deal, but which does not at the moment look too encouraging.

And finally we on this continent would be hiding our heads in the sand were we not to acknowledge quite frankly that in this little island across the Atlantic among many people there is held the view, no matter how captious and how false, that American policy in the Middle East is designed to force the evacuation of British interests, at least in those great and vast oil reserves, and to substitute for them our own.

So much for rather specific though important questions. Since time and space are no longer defenses against great dangers, what happens in other remote parts of the world may easily affect us in our own homelands, each one of the three of us. Should we not try to mold common policies lest we become divided and so are shattered? Is the spirit of nationalism among each of us so strong that we cannot make concessions to our partners in areas of primary concern to one but of secondary concern to another in order to preserve a common course of action? Is this possible or probable for us to achieve, when there is such a strong tendency among us to move toward more and more direct rather than representative democracy? Must we always be forced to deal with issues only when they have been blown up into great crises? Can we not formulate common courses long before the emergency is dropped suddenly in our laps? Are democracies too complacent, too reluctant to take measures of insurance to prevent emergencies from developing into emergencies? Well, here are some of the questions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

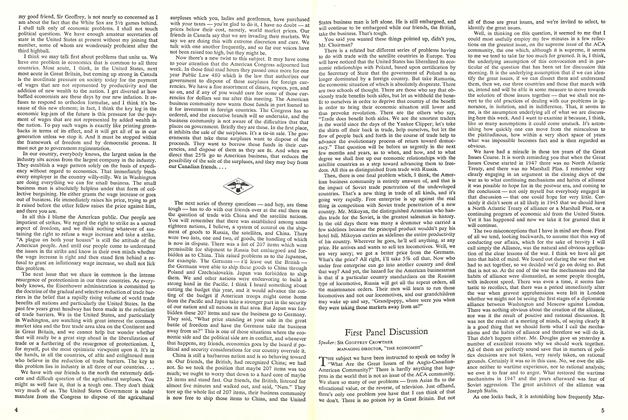

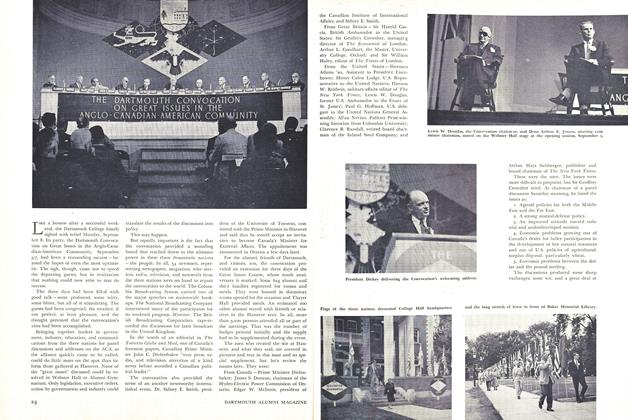

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY -

Feature

FeatureThird Panel Discussion

October 1957 By ALLAN NEVINS

Features

-

Feature

FeatureContemporary Man

DECEMBER 1966 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDARTMOUTH CUP

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

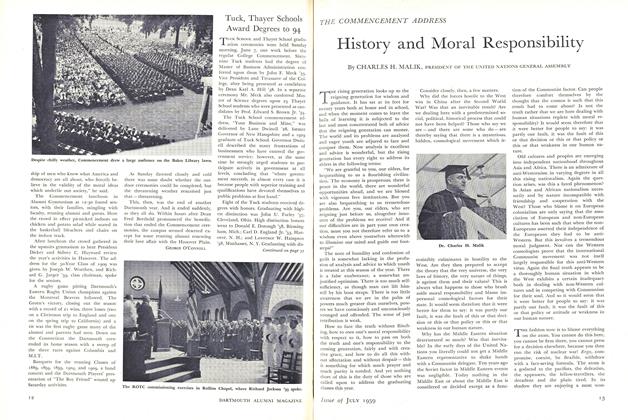

FeatureHistory and Moral Responsibility

JULY 1959 By CHARLES H. MALIK -

Feature

Feature"Veni, Vidi, victus sum."

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Feature

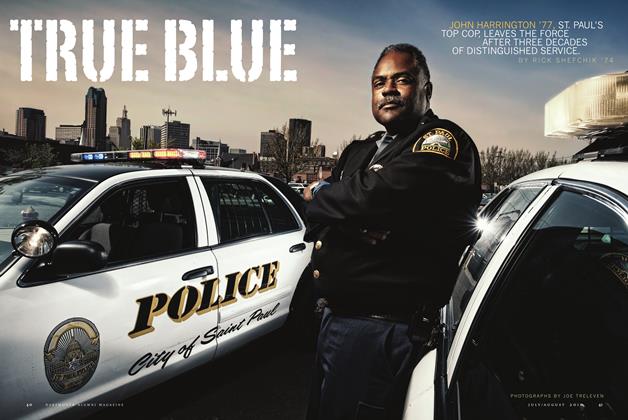

FeatureTrue Blue

July/Aug 2010 By RICK SHEFCHIK ’74 -

Feature

Feature1958 ALUMNI FUND REPORT

DECEMBER 1958 By William G. Morton '28