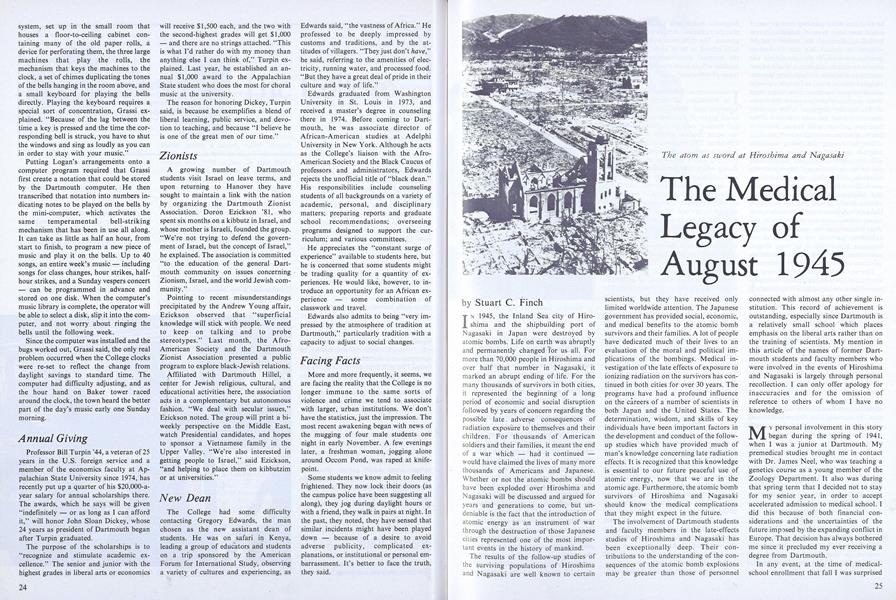

The atom as sword at Hiroshima and Nagasaki

IN 1945, the Inland Sea city of Hiroshima and the shipbuilding port of Nagasaki in Japan were destroyed by atomic bombs. Life on earth was abruptly and permanently changed for us-all. For more than 70,000 people in Hiroshima and over half that number in Nagasaki, it marked an abrupt ending of life. For the many thousands of survivors in both cities, it represented the beginning of a long period of economic and social disruption followed by years of concern regarding the possible late adverse consequences of radiation exposure to themselves and their children. For thousands of American soldiers and their families, it meant the end of a war which - had it continued - would have claimed the lives of many more thousands of Americans and Japanese. Whether or not the atomic bombs should have been exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki will be discussed and argued for years and generations to come, but undeniable is the fact that the introduction of atomic energy as an instrument of war through the destruction of those Japanese cities represented one of the most important events in the history of mankind.

The results of the follow-up studies of the surviving populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are well known to certain scientists, but they have received only limited worldwide attention. The Japanese government has provided social, economic, and medical benefits to the atomic bomb survivors and their families. A lot of people have dedicated much of their lives to an evaluation of the moral and political implications of the bombings. Medical investigation of the late effects of exposure to ionizing radiation on the survivors has continued in both cities for over 30 years. The programs have had a profound influence on the careers of a number of scientists in both Japan and the United States. The determination, wisdom, and skills of key individuals have been important factors in the development and conduct of the followup studies which have provided much of man's knowledge concerning late radiation effects. It is recognized that this knowledge is essential to our future peaceful use of atomic energy, now that we are in the atomic age. Furthermore, the atomic bomb survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki should know the medical complications that they might expect in the future.

The involvement of Dartmouth students and faculty members in the late-effects studies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been exceptionally deep. Their contributions to the understanding of the consequences of the atomic bomb explosions may be greater than those of personnel connected with almost any other single institution. This record of achievement is outstanding, especially since Dartmouth is a relatively small school which places emphasis on the liberal arts rather than on the training of scientists. My mention in this article of the names of former Dartmouth students and faculty members who were involved in the events of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is largely through personal recollection. I can only offer apology for inaccuracies and for the omission of reference to others of whom I have no knowledge.

MY personal involvement in this story began during the spring of 1941, when I was a junior at Dartmouth. My premedical studies brought me in contact with Dr. James Neel, who was teaching a genetics course as a young member of the Zoology Department. It also was during that spring term that I decided not to stay for my senior year, in order to accept accelerated admission to medical school. I did this because of both financial considerations and the uncertainties of the future imposed by the expanding conflict in Europe. That decision has always bothered me since it precluded my ever receiving a degree from Dartmouth.

In any event, at the time of medicalschool enrollment that fall I was surprised to find Jim Neel standing next to me. I asked him what type of medicine he intended to practice. He replied that he wanted to devote his life to human genetics, since he felt that the subject was poorly developed and that it would be important to medicine in the future. My ambition at that time was to become a general practitioner in my home town. Then came Pearl Harbor. Well do I recall the drama of that Sunday afternoon in the anatomy laboratory when we were informed of the outbreak of war with Japan. Within a few months, we were all in uniform.

Despite a very demanding academic schedule, Jim Neel as a student made some scientific observations that subsequently proved to be extremely important. His research elucidated the inheritance mechanisms for both sickle cell anemia and Mediterranean anemia. His observations clearly proved that the parents of children with these crippling disorders were asymptomatic carriers of the traits and that transmission in man followed established patterns of Mendelian inheritance. It was difficult for many of us as students at that time to appreciate the importance of those pioneer observations.

The war with Japan ended during the summer of 1945, within days of the detonation of the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The first was exploded near the center of the city at 8:15 a.m. on August 6, at a height of about 500 meters above the ground. The bomb had a force equivalent to about 12,000 tons of TNT. The Nagasaki bomb was exploded three days later at about 11:00 a.m., also at a height of approximately 500 meters above ground. Although the Nagasaki bomb was twice as powerful as the Hiroshima bomb, it caused only about half the number of immediate casualties, because Hiroshima lies in a flat delta and the area destroyed was a congested residential and industrial section. In contrast, the Nagasaki bombing occurred over a much less densely populated area, located in a long narrow valley.

The atomic bomb survivors in the two cities who received any appreciable amount of radiation were within 2,000 meters of the hypocenters. Most of the irradiation of the people occurred during the first few seconds following the detonations. Radioactive fallout in both cities was minimal since both explosions were well above ground level, thereby resulting in very little soil contamination. There were significant differences in the types of radiation released from the two bombs. The reactor in the Hiroshima bomb was uranium 235, which produced both neutron and gamma radiation. The core of the Nagasaki bomb was plutonium 198, so that the radiation released was virtually all gamma. The differences in bomb structure have proved to be of great importance in the eventual determination of the late medical effects from exposure to these two types of radiation.

IMMEDIATELY following the cessation of hostilities, a team of American scientists and physicians joined with a small group of Japanese doctors, nurses, and medical students in order to evaluate the acute medical effects of the atomic bombings. This organization, known as the Joint Commission, operated effectively in both cities for a period of several months, during which time a number of important medical observations were made concerning acute radiation sickness and other acute medical consequences of exposure to the atomic bombs. Upon conclusion of its mission in the late fall of 1945, the Joint Commission recommended that the United States organize and support a long-term systematic study of the late medical effects of the bombings in the exposed populations of the two cities. In November 1946, President Truman issued a directive to the National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council to undertake long-range medical investigations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This resulted in the eventual establishment in March 1947 of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), with laboratories in both Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Later that year the Japanese National Institute of Health became a partner in the study.

Jim Neel and I were both in medical residency training programs at different hospitals in the States when the war ended. The following spring, again on active duty with the Army, I was sent to Japan to work with the repatriation of Japanese soldiers and civilians from China and elsewhere in Asia. Later, as the Port Quarantine Officer for Japan, I made a visit in early 1947 to Hiroshima, where I again ran into Jim Neel, then a Ist lieutenant in the Army. He was actively engaged in the establishment of the ABCC laboratories and examination centers in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. His primary responsibility was to develop study techniques that would determine the extent of possible genetic damage to the children born of parents who had been exposed to the atomic bombs. His excellence in the fields of clinical and population genetics had been clearly recognized. Jim brought me up to date concerning the plans for the medical investigations in both cities. That was to be my last contact with him for a number of years.

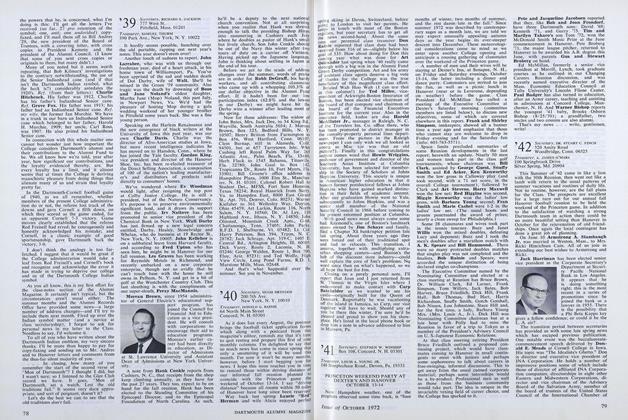

The first major research project sponsored by ABCC was initiated in 1948 under Jim Neel's direction. It consisted of a careful investigation of the outcome of about 70,000 pregnancy terminations in the two cities for evidence of possible radiation-induced genetic effects. Emphasis was placed on the possible detection of congenital malformations, significant alterations of birth-weight, and the frequency of stillbirths. There was close to 100 per cent identification of all pregnancies atthat time, since pregnant women were entitled to an extra ration of rice for which registration was necessary. Much of the success of the early genetics studies may be attributed to the efforts of Duncan McDonald, then a zoology instructor at Dartmouth and now a member of the Middlebury College faculty. Arriving on the scene in 1951, he established close contact with midwives in both cities, thereby insuring early notification and examination of the new mothers by the ABCC.

The genetic study continued through 1954. Despite many ominous predictions, the genetics team found no evidence of increased malformations, stillbirths, abnormal birth-weights, or other problems in the children born of parents who had been exposed to atomic bomb radiation. There was some question at that time, however, concerning a possible alteration in the normal ratio of male to female among the children born of exposed parents during the years following the bombings. The sexratio portion of the study was therefore continued for several more years, with the eventual conclusion that it was not possible to demonstrate an effect of . parental irradiation in influencing the sex of their offspring.

The first definite late effect of atomic bomb radiation exposure detected was the occurrence of radiation cataracts. The characteristics of these eye lesions were carefully described and reported by Dr. David G. Cogan '29 of the Harvard medical faculty and his associates in the early 19505. Most of these cataracts were small and their frequency of occurrence was directly related to the estimated amount of radiation exposure. Many other atomic bomb survivors eventually were found to have minimal radiation-induced changes in the lenses of their eyes. These lesions did not impair vision, were observed only by means of specialized ophthalmologic equipment, and have shown no significant change during the subsequent years.

The clinical programs in both Hiroshima and Nagasaki expanded rapidly during the early years of ABCC. Dr. Frank Connell '28 waS recruited from the Zoology Department at Dartmouth in 1950 as chief of ABCC Laboratories and later was assigned the major responsibility for the Nagasaki program. Dr. Jarrett Folley, who has recently retired as medical director of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, came from Hanover in 1950 as an ABCC clinical director. Some of the latter's responsibilities were to design medical record and radiation-dose estimate techniques for the atomic bomb survivors. One of his most notable achievements while at ABCC was co-authorship of the first report, in 1952, on the development of leukemia as a consequence of radiation exposure from the bombs. Subsequent observations have shown that a leukemia peak incidence of about 40 times normal was reached in the heavily exposed survivors during the years 1952-53, the highest rates occurring in the children. The incidence of leukemia for all exposed persons has been higher in Hiroshima than in Nagasaki, but the rates in both cities have been related to the severity of the radiation exposure. Leukemia has gradually declined over the ensuing years, but the rate in exposed persons in Hiroshima still remains slightly higher than in the nonexposed population.

Another early and very disturbing observation at ABCC was that irradiation of the unborn fetus while still in the mother's womb resulted in a high incidence of small head-size and mental retardation. These effects were most pronounced if the radiation exposure occurred during the first three or four months of pregnancy. The number of children who experienced this adverse effect was small and frequently the changes were minimal, but the effect was unequivocal. Again the response was greater in Hiroshima than in Nagasaki. The tremendous sensitivity of the fetus during its early stages of development to the adverse effects of ionizing radiation is similar to that which has been reported in infants born of mothers who ingested thalidomide and other toxic substances during early pregnancy.

IN the mid 19505, the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission experienced difficulties in staffing and in the continuation of some of its important research programs. In 1956, a group of outstanding epidemiologists from the United States recommended that the program be drastically revised so that long-term observations could be continued on a fixed population sample. The following year, the Department of Medicine at Yale agreed to help staff the medical program in Japan on a continuing basis. It also was at about that time that Dr. Gilbert Beebe '33, from the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, was sent to Japan to direct the Department of Epidemiology and Statistics at ABCC. Over a period of two years, he redesigned and reorganized virtually all of the epidemiologic programs at ABCC. The medical examination and epidemiologic studies were expertly integrated into an overall broad research plan known as the Unified Study Program, one major component of which involved investigation of the duration of life and causes of death of about 100,000 people in both cities. This information is obtained from the study of death certificates and the results of autopsy examinations. A standardized program of biennial medical examinations for about 20,000 individuals in both cities was established.

In 1960, I went to Hiroshima as the chief of medicine on a two-year leave of absence from my faculty position at Yale Medical School. There is no doubt that my earlier contact with Japan and Jim Neel in Hiroshima had greatly influenced my decision to return. My association with Gil Beebe at that time was very brief since he returned to the States that same year, but it was long enough to appreciate the magnificent job that he had done in reorganizing the program. The experiences at ABCC and the kind and gracious manner in which we were received in Japan during those two years made a deep impression on all members of my family. Our two daughters and two sons, both of whom subsequently graduated from Dartmouth, attended Japanese schools, a very special experience which they have always cherished. The devotion of the scientists and other employees at the commission to the study of late radiation effects was most inspiring. On the other hand, concerns regarding atomic bomb survivor medical care and socio-economic problems were most disturbing. The political potential for exploitation of the bombings often was volatile but never fully erupted.

The early and mid-1960s saw some other important medical observations. Tumors of the thyroid gland were established as a late radiation effect. Study of the chromosomes in the circulating white blood cells of survivors demonstrated abnormalities that were proportional in frequency to the extent of the radiation exposure. Many of these chromosomal abnormalities have persisted, even though it is now over 30 years since the survivors were exposed to the bombs. The relationship between these chromosomal changes and the occurrence of various types of cancer is uncertain at the present time.

The Yale affiliation was responsible for the appointment of Dr. Kenneth G. Johnson and Dr. Marie-Louise Johnson as chiefs of medicine and dermatology, respectively, at ABCC in 1964. During their stay of almost four years in Japan, it was first reported that both lung and breast cancers were appearing as radiation effects in the exposed survivors. Subsequent studies have confirmed the fact that the excess of these cancers in the atomic bomb survivors, in comparison with their non-exposed controls, is due to radiation exposure and not to other environmental factors. The experience in Japan was responsible for Ken's switch to a career in the field of epidemiology and the eventual appointment of both Johnsons to the faculty of Dartmouth Medical School.

In the fall of 1974, I took a six-month leave of absence from Yale and returned to Hiroshima once again. It was my good fortune to be in Japan during a period when Dr. Beebe was just completing a two-year assignment as chief of the Department of Epidemiology and Statistics. His continued devotion to the program was impressive, and his knowledge of the activities most helpful. At that time I also was pleased to renew my acquaintance with Dr. Michael Danzig '66, who was deeply involved in several important cardiovascular disease studies. My brief stay in Hiroshima also was marked by a tragic event which I feel must represent indirectly another casualty of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki story. My son Sheldon '75 and his roommate Herbert Childs '75, in the fall of their junior year, embarked on a trip to visit us in Japan via Europe and the Far East. Things proceeded well until they reached Afghanistan where Herbie suddenly became ill and died. The impact of this single tragic event on the members of our two families defies description.

IN April 1975, the ABCC was dissolved and was replaced by a bi-national organization known as the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF). Scientific and administrative supervision and financial support for the foundation are shared equally by Japan and the United States. At the time of the conversion in 1975, the annual budget was about $11 million, and there were approximately 600 employees in the two cities. The professional staff consisted of 45 members, of whom only seven were American. Inflation has pushed the current annual budget to well over $15 million for a program which has changed little in the past few years.

In the late summer of 1975,1 returned to Japan as a director and chief of research at the newly organized foundation. My major responsibilities were to supervise all research activities, to coordinate Japanese- American administrative functions, and to organize scientific meetings. My research accomplishments in the fields of hematology and immunology provided a great deal of personal gratification. On many occasions I met with the bi-national RERF Scientific Council in order to discuss current and future research plans. A member of the council was Dr. James Crow, an expert in the field of genetics and former faculty member at Dartmouth. He has played an important role in the direction of the research program in Japan.

The tragic events in Hiroshima and Nagasaki have brought me into contact with a number of outstanding Dartmouth graduates and faculty members deeply dedicated to the work involving the atomic bomb survivors. What many of them did was unique and extremely valuable. It would be difficult to over-emphasize the tremendous contributions which Gil Beebe has made to the program in Japan. It is doubtful that he will ever receive sufficient recognition for the many long evenings and weekends he spent working in his office in Hiroshima. My only meeting with Jarrett Folley was in the mid-sixties when I was invited to give a lecture to a class of Dartmouth medical students, and he described to me a little about the early investigations concerning leukemia in Hiroshima and Nagasaki more than a decade before. I met Dr. Connell very briefly during one of his trips to Japan in the early 19605, totally unaware at the time of either his Dartmouth connection or his previous involvement in the ABCC. Although the contributions of many who worked in Japan during those early difficult years should receive greater acknowledgement, Jim Neel's outstanding accomplishments were at least partially recognized in 1974 when he was awarded the National Medal of Science by President Gerald Ford. (Since the mid-fifties, he has been chairman of the Department of Human Genetics at the University of Michigan Medical School.)

THE studies at ABCC-RERF over the years have clearly demonstrated a number of definite late adverse effects in atomic bomb survivors which are due to excessive exposure to ionizing radiation. The major effects have been the lesions of the lenses of the eyes, the blood cell chromosomal aberrations, the retardation of growth and development following childhood exposure, the small head-size and mental retardation of the in-utero exposed, the increased occurrence of leukemia and the more recent development of cancers of the thyroid, lung, heart, breast, and gastro-intestinal tract. The effects are greater in persons exposed early in life than in those exposed later in life. The effects also are greater in persons exposed to neutron radiation than in those exposed to gamma radiation. The leukemia induction now is over, but various types of solid tumors are appearing in excessive numbers. The carcinogenic effect of the radiation exposure is, by far, the most important effect, but the magnitude of this finding should be brought into perspective. Of about 80,000 naturally occurring deaths in the exposed populations of the two cities since 1950, about 500 to 600 are estimated as excess deaths due to radiation-induced cancer. This is a reflection of a moderately increased cancer rate in heavily exposed persons for several types of tumors.

Several borderline findings, including some changes in immunologic function, increased rates of cardiovascular complications, and the occurrence of several other types of cancer, are under intensive investigation. The late effects from either fallout or induced-radiation exposures remain equivocal. Those are most difficult problems to study, since radiation doses for the population at risk are not accurate and the actual number of persons exposed is not known.

The ABCC-RERF studies over these years have also been responsible for some important negative radiation-induction results. In addition to failure to detect any evidence of genetic damage, there has been no demonstrable decrease in fertility, no acceleration of the aging process, nor evidence of life-shortening of the exposed persons of either city from causes other than tumors. There has been no evidence of increased infections or other nonmalignant illnesses. No new or unique disorders peculiar to radiation exposure have been observed. These results must be somewhat reassuring to the survivors of the atomic bombings, but they can not alleviate completely the lingering fear in the more heavily exposed persons of the eventual possible late development of some adverse medical effect. The psychological impact on the survivors has been difficult to judge. Emotional responses have been greatly influenced by the frequent appearance of scientifically unfounded or speculative reports in the news media. Sometimes these reports are instigated by political pressure groups or irresponsible science reporters, but often they are generated out of ignorance or fear. Despite these problems, the exposed persons, their non-exposed controls, and the scientists of both cities have cooperated extremely well with ABCC and RERF over the years. The participation rate of the regularly scheduled atomic bomb survivors in the medical examination program is about 80 percent, a figure probably far in excess of what might be achieved in any similar voluntary medical examination program in the United States. The populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki deserve credit for their support of the research programs at RERF and for the contributions which they are making to man's knowledge of late radiation effects.

THE medical challenges continue in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Much remains to be accomplished, and the years in which they may be accomplished are rapidly coming to a close. The challenge for me was so strong that in 1977 I resigned my tenured faculty position as professor of medicine at Yale in order to spend two additional years in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The story with Drs. Neel, Beebe, Crow, and the others is not over. In the early 19705, Jim Neel decided that some of the newer technological advances in protein chemistry could be applied to the question of whether or not genetic effects were being observed in the offspring of atomic bombexposed parents. Following several years of determined effort, he was able to institute a new program, known as the Biochemical Genetics Program, which commenced in early 1976. In the course of the next six to eight years, biochemical tests will be performed on about 30 blood proteins from about 25,000 children of both exposed and non-exposed parents in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A search will be made to determine whether or not a greater number of non-inherited mutations occur in the blood proteins of the offspring of the exposed parents as compared with the children of non-exposed. A potentially important biochemical technique which may increase sensitivity of the study of possible inherited disorders recently was developed during a summer fellowship in Hiroshima by John Urbanowicz '76, who went from Dartmouth to medical school at the University of Rochester. The Biochemical Genetics Study will go hand in hand with another study that will examine a somewhat smaller number of first-generation offspring children for the ocurrence of chromosome abnormalities in their white blood cells.

An intensive search for late radiation effects continues at RERF. Many of the persons who were exposed during childhood, infancy, or fetal life are just entering the age when they normally experience an increase in development of cancers. It is essential that they be carefully watched for evidence of an increased tumor incidence or for increased mortality' from any cause. Focus in the medical examination program of the survivors is being directed at early cancer detection and cancer education. Another research area which is intimately concerned with the cancer problem is that of the immunologic competence of the survivors. It is known that, with aging or following certain types of radiation, the ability to produce antibodies and certain other immunologic functions may be transiently or permanently impaired. Some of these changes may be of importance in the development of cancer. Advances in techniques in the past five to ten years have been rapid. It is now possible, on small amounts of blood from individuals in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to do sophisticated immunologic studies that may be useful in the early detection of their cancers and may contribute to man's knowledge of the process of tumor development.

Gil Beebe recently retired from his position at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, but he immediately accepted a new position with the Clinical Epidemiology Branch of the National Cancer Institute. He continues to work vigorously with groups concerned with late radiation effects and radiation safety standards for now. His ideas often provide the stimulus for new avenues of research for investigators in Japan.

Questions frequently are asked concerning the practical value of the information coming from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. There are several components to the answer. One of the most important is that the medical facts are of great value to the exposed survivors themselves. The large backlog of reliable scientific information provides the basis for elimination of much of the fear which is derived from the rumor and speculation associated with the unknown. Another substantial benefit from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki experience is the direct application of the results to the development of radiation safety standards for the peaceful use of atomic energy. There are many theoretical and experimental ways of determining the dangers of radiation exposure for man, but by far the most reliable and most useful information has proceeded from the experience in Japan. The medical results have been published in a number of international and United States government reports. The fact that there were differences in the quality of the radiation released in Hiroshima and Nagasaki also is of great importance. This information has been useful in the determination of safe gamma and neutron tolerance levels. Finally, it is hoped that wide dissemination of information concerning the adverse late medical effects of atomic bomb exposure will constitute a powerful deterrent to any future use of atomic energy as an instrument of war.

It is inevitable in the years ahead that man will continue to be exposed to potentially dangerous amounts of radioactivity. It is quite possible that the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki may eventually result in the saving of many lives if the lessons of these cities are properly applied to the new generations at risk.

Eight years after the bomb: a group of midwives testifying with Duncan McDonaldduring a conference of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission in Hiroshima in 1953.

Stuart Finch '42, as head of thehematology unit at Yale, also did extensiveresearch in sickle cell anemia. His sons areJames '7l and Sheldon '75. Dr. and Mrs.Finch have recently returned from Japan,and he has become a professor of medicineat Rutgers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

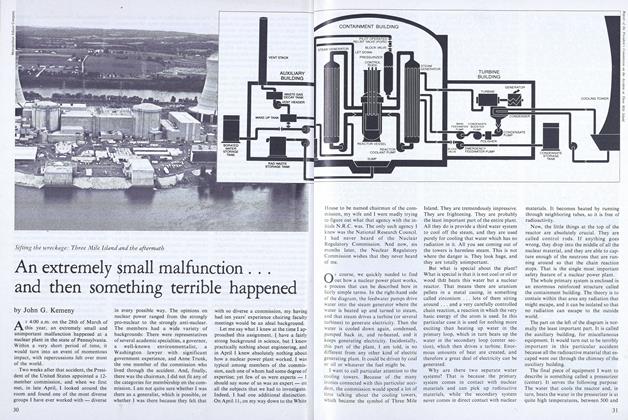

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Books

BooksThe Country Remembers

December 1979 By R.H.R. -

Article

ArticleThe Five-Year Plan

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

December 1979 By JOHN L. GILLESPIE

Stuart C. Finch

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StorySUNDIAL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureA Thinking Man's TV Journalist

June 1960 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Cross Section of Existence

MARCH 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

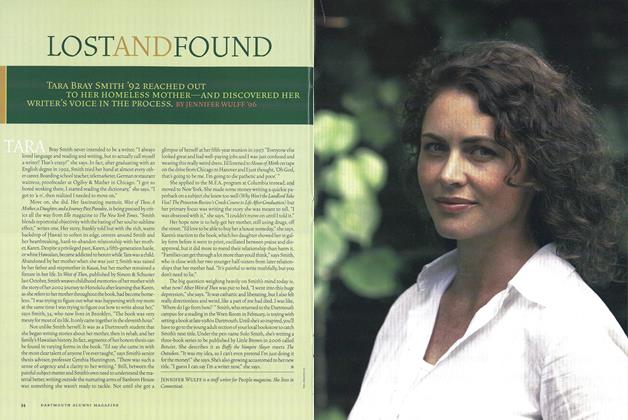

FeatureLost and Found

May/June 2005 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

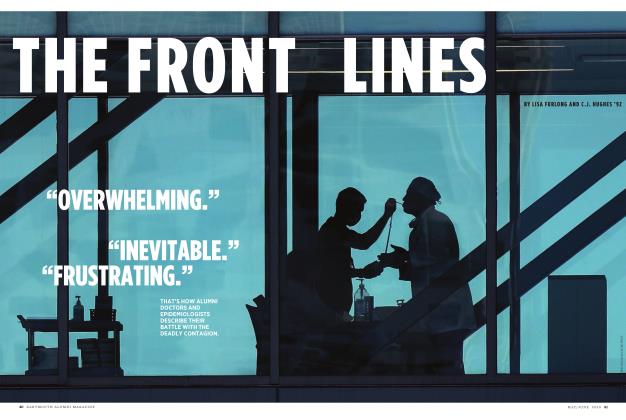

FeatureThe Front Lines

MAY | JUNE 2020 By LISA FURLONG, C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureHotsy Totsy

APRIL 1982 By Lomax Littlejohn