Dartmouth professors complete a long study of military education's handling of a new role for top U. S. officers.

FOR the past three years two Dartmouth professors have been spending a lot of time in the Pentagon. They put in a lot of time also at Annapolis, West Point, and the new Air Force Academy at Denver. Planes and trains whisk them off, together and singly, in frequent round trips to the war colleges in Washington, Newport, Carlisle Barracks (Pennsylvania), and Montgomery (Alabama).

Indeed, they are as often at work in these eight establishments out of town as they are in their Hanover classrooms and lecture halls. During summer vacations when many members of the faculty hole up in Baker Library trying to get caught up on important books unread during the press of the year's academic duties, these two, having coordinated their findings in their Hanover offices, load themselves down again with heavy briefcases and are off again on their military-civilian investigations.

Members of the Department of Government, these two professors, Masland and Radway by name, are convinced that these outside adventures have improved their effectiveness in seminars, classes, and lectures. Their experiences illustrate the ways research and scholarship can reinforce the central teaching function at Dartmouth.

John W. Masland and Laurence I. Radway now figure significantly in serious discussions of higher military education and the preparation of career officers for policy roles in such organizations as the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Staff, the Army and Navy and Air Force Departments, and the SHAPE headquarters in Paris.

The Masland-Radway findings will be examined by professional educators throughout the country. Even more important, these findings will affect military and governmental thinking at top levels. And the Masland-Radway findings have resulted in a book of the first importance to all Americans concerned with American leadership in a world desperately in need of it.

Published by the Princeton University Press this month, the book is entitled Soldiers and Scholars: Military Educationand National Policy. It is concerned with professional military education, and most particularly with the methods and manner in which the armed forces are now preparing their career officers for duties involving national policy formulation.

It examines in most detail the National War College, the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, the Army and Naval and Air War Colleges, and the three service academies. Some attention is devoted to the Armed Forces Staff College, to the Command and Staff Schools, and to the Reserve Officer Training Corps programs. And some consideration is given to the use of civilian institutions by military personnel for advanced education.

Now that atomic and thermonuclear weapons and threats of massive annihilation as instruments of national policy seem less adequate than perhaps they used to, thoughtful persons would like to be assured that professional military officers can adapt creatively to changing circumstances. One wonders whether they have resiliency in adapting themselves to civilian leadership or whether deep down they resent it. One would like deferentially to inquire whether the highest officers in our armed forces are properly motivated about their positions and whether it is possible for some to get stuck in a rut and to place their own branch of the service ahead of the others. Can they cooperate with officers in foreign countries or are they (and the foreign officers, for that matter) hamstrung by provincialism?

Pride in the history of Navy and Army and Air Force and in their individual traditions is admirable, but one may be permitted to query whether it may not degenerate on occasion into conformity. If there are conformists at top levels, one would like to be reassured that they are free from insidious dogmatism, rigid orthodoxies, and stiffened policies. A criterion would be whether the higher level military schools are now and in the future willing to make energetic and reasonable challenges of basic assumptions and at the same time to free themselves from the domination of the policy-making centers of their own services and the government.

For example, it may well be that no one general or admiral and no one government office has the answers to such questions as these:

1. Have we analyzed objectively the goals of other nations?

2. Will our present military organization students of 1957 come into positions of supreme authority about 1980?

3. Should we cooperate more fully with officers work with us on American soil with American equipment and by having our officers in analogous positions on foreign soil?

4. How effective are stockpiles of nuclear bombs as deterrents for local wars that spread?

Surely military officers today, moreover, ought to be able to understand, to communicate with, and to evaluate the judgment of political leaders, officials of other executive agencies, and countless specialists. Whether military officers like it or not, they are certainly called upon today to assess the motivations and the capabilities of foreign nations and to estimate the effects of American action or inaction upon these nations.

Highly important is the need for military leaders to comprehend what democratic principles are, why they are in conflict with totalitarianism, and why the free world has such life-and-death stakes in them.

THESE are the sorts of questions and considerations arousing the curiosity of Professors Masland and Radway. They are particularly eager to determine the adequacy of the educational preparation of officers for policy-making positions. In addition to preparing their graduates for conventional military duties, do West Point, Annapolis, and the new Air Force Academy provide the basic educational foundation for a career of ever-increasing and complex responsibility? And what about the senior professional schools? Do they produce generals and admirals competent not only in military affairs but also capable of grasping the large and complicated problems of the world today?

If these Dartmouth professors were to make such a study, they would first have to find leisure and funds. President Dickey and Provost Morrison encouraged them and suggested the necessary arrangements about release from full teaching loads. The Carnegie Corporation of New York, whose vice president, James A. Perkins, has a long-standing interest in civilmilitary relations, provided the requisite funds in a substantial grant to Dartmouth College. Lieutenant General Harold A. Bull, USA (Ret.), former commandant of the National War College, on whose faculty Professor Masland had served, and Colonel George A. Lincoln, head of the Department of Social Sciences at West Point, provided encouragement and counsel all along the way. Fortunately also the Brookings Institution provided a headquarters from which to conduct field work in Washington.

With these kinds of support, Professors Masland and Radway set to work in the spring of 1953. They reasoned that before examining the educational programs conducted for military officers they should first evaluate the demands placed upon these officers. So they began to ask the sorts of questions anyone would ask, especially trained educators, about what precisely has happened since World War II when the best military minds found that they must work with the best civilian minds not only in government but also in scientific research and development, and other fields. Traditional distinctions, it was felt, were being broken up, and the military were engaged in activities far beyond the conventional pre-war boundaries of military functions and affairs.

For these demands, are the minds of potential military statesmen being properly oriented and disciplined? Professors Masland and Radway found a singular lack of books and articles dealing in any fundamental way with the preparation of senior officers for their roles as associates with civilian authorities making decisions of national and international importance. Although today the military are not only deeply concerned but also active in solving these problems, no systematic evaluation of their early attempts and their present-day achievements was available. During three years of close observation and analysis of military schools in operation, Professors Masland and Radway have provided detailed evaluation in their book.

IN reducing the teaching loads of Professors Masland and Radway, the President and Provost of Dartmouth College assumed that their teaching would benefit and that their students would profit by the impingement upon their courses of their professors' experiences outside Hanover.

Masland offers courses in international affairs and American foreign policy; and Radway, in American government and public administration. In these fields the men found countless opportunities to bring to bear their newly enriched insights into the intimate relationship of military to political, economic, and social affairs. Both have introduced into their syllabi material discovered in the course of their research, as well as some prepared pared by themselves. In connection with their investigations, they brought to Hanover numerous individuals, almost all of whom they took into their classes. These include professional military officers and civilian officers in the Department of State.

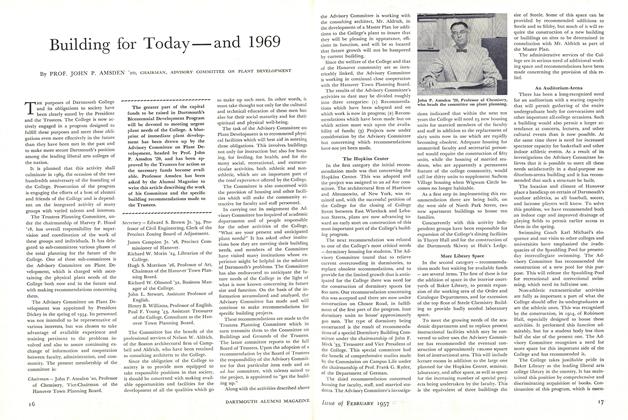

Partly as a result of these visitors' suggestions, a study of the impact of technology upon the problems of American security has been included in the Great Issues Course, and Professor Masland was called upon to give one of the lectures on this topic. He and Professor Radway, moreover, have introduced an experimental seminar, Government 74, on selected problems in civil-military relations. Consequently Dartmouth undergraduates consider, as best they can by reading, analysis, and discussion, the sorts of problems encountered by the President of the United States and his advisers in the National Security Council, the civilian officials in the Department of Defense, and the members of the House and Senate Armed Forces Committees, and other members of Congress. The government professors insist that these problems should be the concern of all intelligent Dartmouth men as future citizens.

Older alumni may find that classroom procedure differs radically from the former routine of three fifty-minute class periods a week with lectures by professors who on occasion permitted some recitation by students. This seminar, Government 74, meets only once a week, on Wednesday afternoons, and lasts for two hours and a half. For the first half of the seminar, general topics are considered: the dimensions of military affairs, strategic concepts and foreign policy, and the organization for security policies formulation. During the second half, individuals prepare substantial papers and make reports on selected topics like civilian control of the military, manpower utilization, career incentives, mobilization, military aid problems, and Congress and the Armed Forces.

As political scientists, Masland and Radway found that one of the most stimulating features of their experiences outside Hanover was exposure to the other social science disciplines and even to the physical sciences and to the humanities. In evaluating military education, they had to study these fields beyond their own areas of specialization. At Dartmouth they obtained considerable help from some colleagues in other departments. At one stage of their work, when they needed to design and administer a lengthy questionnaire to more than 500 officers stationed in the Pentagon, they added to the team an experienced sociologist and statistician, Dr. Andrew F. Henry, then of the Laboratory of Social Relations at Harvard University and now of Vanderbilt University.

Masland and Radway testify that Henry not only introduced them to the mysteries of IBM punchcards and tabulating machines but also subjected their research methods to the most rigorous testing and thereby sharpened their analytical skills. The Dartmouth men like to think that they also taught the Harvard-Vanderbilt statistical authority a few things about political science. Incidentally, this association with Dr. Henry led to the publication of an article in the Public Administration Review on the attitudes of officers on the Joint Staff, an unforeseen by-product of the larger study of military education.

Professors Masland and Radway feel that in still other ways their leaching competence has been strengthened by their research experiences. To both have come opportunities to participate in other ventures in the broad area of civil-military relations, such as panels of the American Political Science Association, the American Society for Public Administration, a study group of the Council on Foreign Relations, the Defense Studies Seminar at Harvard University, and the Strategy Seminars conducted annually by the Army and Naval and Air War Colleges. Both professors served as consultants to task forces of the Hoover Commission. Masland is now serving on the National Security Policy Research Committee of the Social Science Research Council, which is attempting to stimulate scholarly investigation of the interrelationship of military and political affairs. To this end it is administering a promising fellowship program, which hopefully will enlarge the small pool of experienced investigators in this field.

To return to the book—all thinking Americans are likely to find it absorbing because it deals with the survival of the United States in a hostile world. In a cooperative work involving scores, perhaps hundreds, of persons as collaborators, the two Dartmouth professors express their own opinions and convictions. The book has good words to say concerning the professional education of our top military leaders, but it has also words of grave warning as well.

Dartmouth men in particular will find Soldiers and Scholars: Military Educationand National Policy worthy of careful examination not only because Masland and Radway are members of the Dartmouth faculty but also because they write out of their own convictions that in professional and military education the liberal arts colleges occupy a central position.

They are themselves products of undergraduate liberal arts colleges (Masland, Haverford; Radway, Harvard), and both their graduate-school education and their teaching experiences have been in institutions firmly rooted in the liberal arts traditions.

And, finally, it is news of the first order when the highest ranking officers in the Army, Navy, and Air Force in perfect confidence open their files, their minds, and their hearts to two Dartmouth professors of government to enable them to write a book in which the contents of their files and minds and hearts, products of the higher military education, are to be studied, analyzed, and presented to the nation in a university press book.

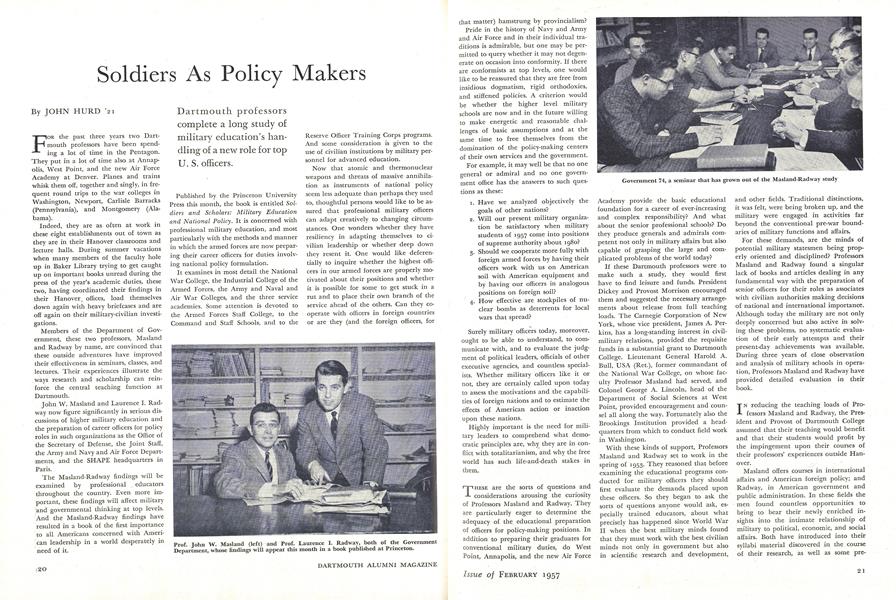

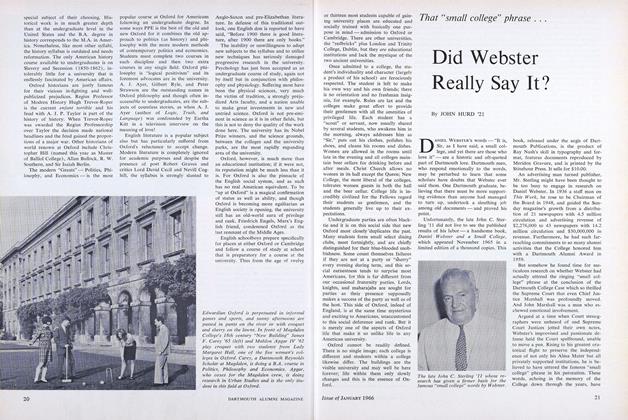

Prof. John W. Masland (left) and Prof. Laurence I. Radway, both of the Government Department, whose findings will appear this month in a book published at Princeton.

Government 74, a seminar that has grown out of the Masland-Radway study

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBuilding for Today—and 1969

February 1957 By PROF. JOHN P. AMSDEN '20, -

Feature

FeatureA Running Start

February 1957 -

Feature

FeatureTo Make What's Good Better

February 1957 By R. L. A. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

February 1957 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1957 By JOHN H. RENO, PETER B. EVANS, CHARLES G. ENGSTROM

JOHN HURD '21

-

Books

BooksBOSWELL IN SEARCH OF A WIFE, 1766-1769. Edited

January 1957 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksPOLITICAL WRITERS OF THE EIGHT-EENTH-CENTURY.

MAY 1964 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureDid Webster Really Say It?

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksUNDER THE ROCK, POEMS FROM A VALLEY.

JANUARY 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSEVENTY NEW POEMS.

JANUARY 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksAN ESSENTIAL SHAKESPEARE: NINE PLAYS AND THE SONNETS.

OCTOBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Woodsy Time Line

NOVEMBER 1989 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Starscape That Is Just Amazing"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Feature

Feature"The Nasties Upset Since Bunker Hill"

FEBRUARY 1959 By COREY FORD '21h -

Feature

FeatureReunions, 1970 Style

JULY 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

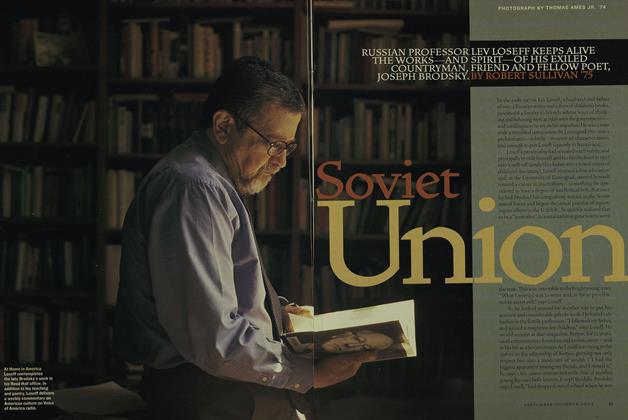

FeatureSoviet Union

Sept/Oct 2005 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Mold

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Warren Cook '67