By Allan Macdonald. Durham:Duke University Press, 1957. 265 pp. #5.00.

It is hard to think of this portrait of Hovey as anything other than Allan Macdonald's book. Any man who sat under Allan Macdonald in a Hanover classroom, or who shared a seminar in his house on Hovey Lane, must come to read this biography with double affection: here is the author of Dartmouth's best songs as seen by one of Dartmouth's greatest teachers.

This book is in many good ways nothing less than another course with Allan Macdonald. Yet to want that alone is antithetic to everything he taught, and the book is final evidence of his catalytic ability to charge with light and heat a subject to which his students might at first come coldly. His chapter on Hovey's undergraduate days is typical: here is Dartmouth under President Bartlett recreated with scholarly devotion to the last detail of campus politics; here is Hovey, carousing and "sowing... another Wilde oat" in the old Hanover that "was within sight of a superbly modeled mountain, and close to the gullied fields which cup the winter shadows." The wit and immediacy of detail are pure Macdonald, as always, but the brilliance of the writing reflects no more or less than the act of dedication that this biography is; the focus is continually on Hovey.

As Hovey grows through these pages into the poet he would become, the wonder is that Allan Macdonald could demonstrate, with the same lively perception that marks his chapters on Hovey's youth, the problems of being a poet in late 19th century America. His understanding of the editorial and financial pressures that Hovey faced is nothing less than complete, and his social insights into the world of Delsartism are as wise as they are humorous. The wisdom here, as in his classes, is never restricted by dead Germanic scholarship; his study is alive to human values at the same time that it is grounded in the most penetrating kind of research. This point is particularly clear in his investigation of Hovey's complex loyalties to his parents and to Mrs. Russell. The treatment of the latter relationship is a model of biographical decorum, being informed by great compassion for the dilemmas of a love affair which began and grew beyond conventional grounds, yet making painfully clear that "such love is tragic because it denies harmony by division within the soul and peace between society and the individual."

Man and Craftsman is more than a casual subtitle to this book: it measures both an admiration for Hovey's virile nature and a sympathetic (but never patronizing) consideration of his limitations as a poet. Even as he passes judgment on the romantic excesses of Hovey's revolt against naturalism, and on the excessive praise won by the wrong poems, Allan Macdonald demonstrates Hovey's experimental concern for the surprisingly modern prosodic techniques which he could briefly control but never sustain. He shows that Hovey the translator (of Maeterlinck and Mallarmé) was of real importance as a publicist for what was then new to the English language, and he places Songsfrom Vagabondia in the perspective of Hovey's more considerable poems.

For most fraternity men, the important work is not Taliesin or "Seaward," but the incidental "Stein Song" which was part of the long poem Hovey delivered to the 1896 national convention of Psi Upsilon, in that remarkable spring when the literary exercises of the fraternity were attended by over a thousand people. As if for all Dartmouth men, the Baker Prize of that same year was awarded to "Men of Dartmouth," like the "Hanover Winter Song" two years afterward, a late but full flowering of Hovey's concern for his college. Hovey died before those poems became a full part of the Dartmouth they so surely defined; Allan Macdonald died before his definitive study could become a part of American literary history. Hovey's words, "the still North remembers them," might stand fairly for both men, yet whoever reads this doubly human book with the present Dartmouth before him cannot be still in either mind or heart.

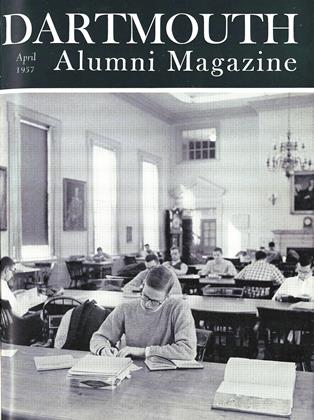

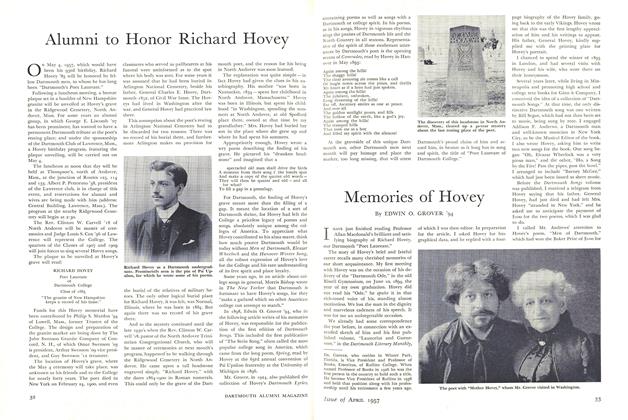

A portrait of Richard Hovey '85 which hangs in the Hovey Grill of Thayer Hall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA New Educational Program

April 1957 -

Feature

FeatureNever Say Die or Adversity Foiled the Story of 100 Years of Rowing

April 1957 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

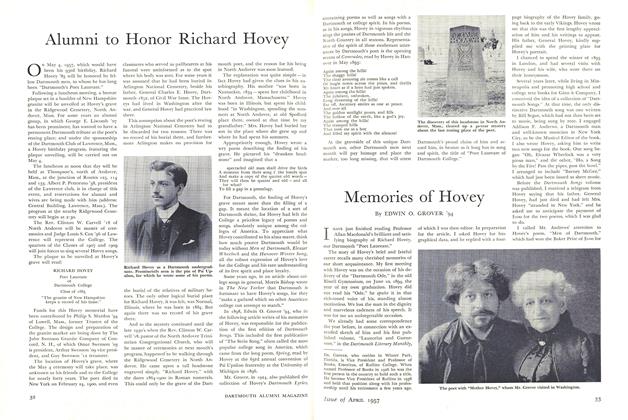

FeatureAlumni to Honor Richard Hovey

April 1957 -

Feature

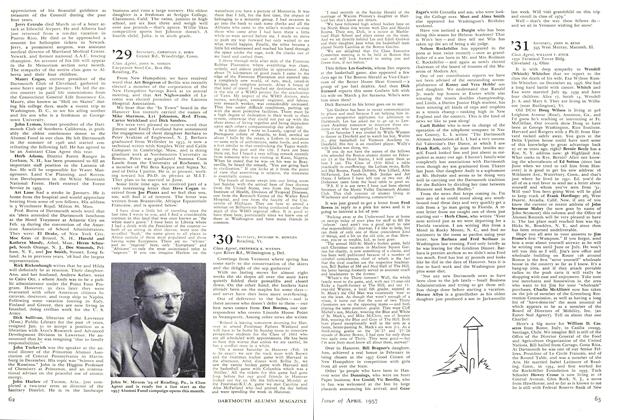

FeatureMemories of Hovey

April 1957 By EDWIN O. GROVER '94 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1957 By JOHN H. RENO, WILLIAM F. STECK

PHILIP BOOTH '47

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

January 1954 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

March 1957 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

September 1976 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorMind and Matters

NOVEMBER 1999 -

Article

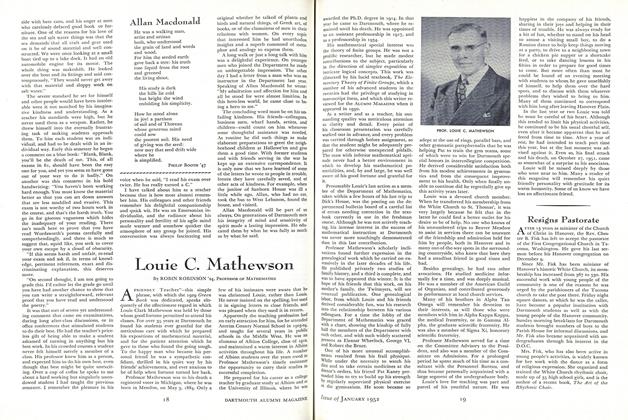

ArticleAllan Macdonald

January 1952 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Books

BooksTHIRTY-FIVE DARTMOUTH POEMS.

JANUARY 1964 By PHILIP BOOTH '47

Books

-

Books

BooksA New-Englander in Japan (Daniel Crosby Greene)

AUGUST, 1927 By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Books

BooksESSAYS ON CATHOLIC EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES

June 1942 By Howard F. Dunham '11 -

Books

BooksTHE STRANGEST BOOK IN THE WORLD:

MARCH 1964 By JOHN W. ZARKER -

Books

BooksTHE LAND OF RUMBELOW.

JANUARY 1964 By R. J. B. JR. -

Books

BooksAMERICAN LABOR TODAY (Reference Shelf, Vol. 37, Number 5).

JULY 1966 By ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Books

BooksTHOMAS CRAWFORD: AMERICAN SCULPTOR.

OCTOBER 1964 By WINSLOW B. EAVES