GOME March and Income Tax time, I can usually dig up my Social Security number to list on a Form 1040, but I get evasive about my occupation and never know what to put down. I feel the same way about party formalities, when somebody comes up to me over a refill and says, always a little too loudly, "I hear you're a poet." The challenge is clear: talk iambs, muss up your hair, or deny it.

I get inclined to take a Fifth Amendment about there, but my curiosity catches up with me and asks back: "Where'd you hear that?" I used to keep hoping the answer would be "in a poem." But real readers never waltz up to a poet in that tone of vice, and I suspect now that a poet gets cornered for much the same reason I once stopped a man (his olive halfway from martini to mouth) with the frontal assault: "I hear you're an astrophysicist." What is astrophysics, I wanted to know, and why be an astrophysicist, and what do you do if you are one? But my ignorance, typically, was not knowing any right questions to ask, and he —as embarrassed as I was - could only swallow his olive and admit that he did "teach physics." Probably he gives in, the way I do, and lists himself as Teacher on a tax form. Like most writers, I wish I were sure enough of what I've written and what I've got in me to write to put down Occupation: Poet. (Robert Frost, owning twelve poems a year for fifty years, four Pulitzer Prizes, and a piece' of Vermont, still taxes himself as Farmer.) A friend of mine, a novelist, confuses the government every spring by claiming he's a poet, but being a poet is being occupied with writing a poem, not filling out tax blanks or deducting from the truth by talking partytalk. And writing a poem is too rare and dark and private an act to make a statistic of or boast about over bourbon.

Making a poem is like making love: a reach to complete a relationship. And trying for a sense of true relationships is the poet's concern, just as it is the astrophysicist's, light-years away. One uses mathematics, the other metaphor, but both are searching for some hidden order in apparent chaos; and both survive by discovering that order does exist, and that chaos is mostly in man's unwillingness to reach beyond it. An astrophysicist sets his sights on a star, and calculates; a poet figures to stake his insight on a stormy love affair with the world. For him, "the world is a wedding, for which the ceremony has not yet been found." Who wrote that I wish I knew, but I do know that a poem can be the ceremony: the revelation of a union (as if with life itself) grown from those relationships that a poet writes to find. A poem is words making a motion toward meaningful wholeness; a poet's work is writing-out, vision and revision, the awkward wonder of his human trials, with men, women, machines, owls, islands, trees, mountains, fish, and (sometimes even) God. His hope against hope is for a poem which, like music, can be "a momentary stay against confusion."

Poems, like love affairs, are mostly failures compared to the hope that starts them, and they often seem more confused than clear in the end. But as he tries to penetrate through the transparent world of Reader's-Digested platitudes, or Madison Avenue myths, the poet risks a deep look into (not only at) the real complexity of human experience, and his words are a measure of its beautifully difficult truth. His poems, like life, may be full of symbols and irony and paradox, but in a poem (as seldom in life), these confusions are stayed, toward the possibility of reflection upon them.

Mostpeople, as any poet and his pocketbook know, are so blinded by bigscreen TV that they've lost the power to reflect. And since a poet is at best an amateur, he doesn't hope to compete with the professionals who sell soft soap, for the audience which loves to be sold. Occupation:Poet is, rightfully, an economical impossibility. But Preoccupation: Poetry survives (as it always has), and it is for people preoccupied with the unwritten poetry of human experience that the poet finally writes.

"I hear you're a poet" is a party preoccupation, however well meant. A poet wants to be recognized by his poems, not by the fallacy that he's as individual as his best work. He isn't. He has nosecolds, children, mortgages, birdfeeders, mice, and a job; to keep or get rid of as best he can, in poems or out. He may even have gone to Dartmouth, like any one of a dozen contemporary poets who deserve to be read. For whatever light a poet casts, into a poem, must meet a reader's eye to have meaning. An average reader doesn't pretend to understand astrophysics, admitting he's forgotten algebra and never took trig. But faced, say, with the calculus of a poem by E. E. Cummings and maybe remembering a symbolic C + in Freshman English), he hates to admit that Time's big guns have knocked holes in his ability to read words in their root sense.

The result is a world of unread books. And given most poems which appear periodically, in The Atlantic, or TheHudson Review, or wherever, the reader can't wholly be blamed. Most poems are dull, unforgivably. But the best are alive, as human beings are who'll risk being human. And the evidence, for ALUMNI MAGAZINE readers, is as close as the work of some Dartmouth poets, work which will survive all Sputniks as a log of where we are now, and of who, humanly, we may yet become.

Mr. Frost's Complete Poems .is too full of stars to chart. But for a late night of looking, try the magnitude of these familiar few: "Mending Wall," "Fire and Ice," "Desert Places," "Design," "The Gift Outright," "Neither Out Far Nor In Deep," "Provide, Provide," and "Directive." And, another night, look up "The Fury of Aerial Bombardment," "If I Could Live..."New Hampshire, February," and "The Groundhog," from Richard Eberhart's Selected Poems. Or search for poems by William Bronk or Reuel Denney or Alexander Laing, all of whom print rarely for the good reason that good poems are always rare. I keep wanting to name more poets, more poems, more books; but poems should, like sipping-whiskey, be taken neat, and slow. Like the best poems in Samuel French Morse's The Scattered Causes, or in Richmond Lattimore's great translations, which (like his own lyrics) are vintage stuff, to be savoured on the tongue, to be read aloud. Or sample The New Poets ofEngland and America, a paperback anthology which includes the work of several younger Dartmouth graduates, and was co-edited by Robert Pack, whose first book owned that fine title, The Irony ofJoy.

Are these poems "difficult"? Of course. Poems continue to be difficult, to write and to read, in precisely the same degree that life has always been hard, to define, and to live. Poetry is not an easy question of being taxed; finally and ironically it is the possibility (in any occupation, whether farming or astrophysics) of being preoccupied with our human potential for salvaging - from whatever chaotic cocktail parties - the joy of being alive; and of finding right words for the world we take (for better or worse) as our own.

Philip Booth '47, Assistant Professor of English at Wellesley, is the author of "Letterfrom a Distant Land," a collection of poemsawarded the 1956 Lamont Prize by the Academy of American Poets. He is currentlywriting on a Guggenheim Fellowship.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

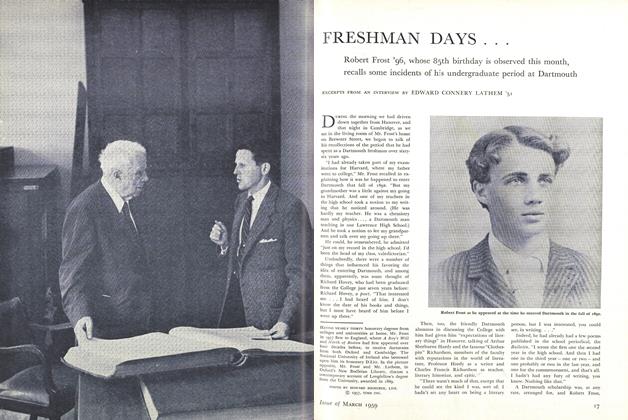

FeatureFRESHMAN DAYS...

March 1959 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature"Spoiled Children" of Hanover: A Letter from Charles Doe, 1849

March 1959 By JOHN P. REID -

Feature

FeatureSCHOOLMARMS, GRAMMARIANS and ANARCHISTS

March 1959 By ROBERT S. BURGER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1959 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1959 By ROBERT L. MAY, EDWARD J. HANLON, BRUCE W. EAKEN

PHILIP BOOTH '47

-

Article

ArticleRobert Frost '96, Non-Graduate

May 1954 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Books

BooksRICHARD HOVEY — Man and Craftsman.

April 1957 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Books

BooksTHIRTY-FIVE DARTMOUTH POEMS.

JANUARY 1964 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Books

BooksA Philosophical Poet, Full Of Wonder

April 1977 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Books

BooksA Life of Their Own

September 1980 By Philip Booth '47 -

Article

ArticleResonance

OCTOBER • 1986 By Philip Booth '47

Article

-

Article

ArticleNOTES

May, 1914 -

Article

ArticleNewcomers Among Our Contributors

DECEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleSpecial Dorms for Married Veterans

November 1945 -

Article

ArticleNew Courses

October 1947 -

Article

ArticleADDRESS TO THE STUDENTS AT THE OPENING OF COLLEGE SEPTEMBER 18, 1913

By Ernest Fox Nichols -

Article

ArticleSTORM WARNING

December 1936 By ROBERT A. SELLMER '35