WAKING TO MY NAME New and Selected Poems by Robert Pack '51 Johns Hopkins, 1980. 250 pp. $15.95, hardcover; $6.95 paper

As poet, and as teacher of poets (as director of the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference and Abernethy Professor of American Literature at Middlebury), Robert Pack has every good reason to consider the publication of these new and selected poems as the crown of an already distinguished career. To the 110 poems he has here collected from his first six books, he has added the 21 new poems that give his book its title and its deepening realization that, as he says, "most of the full of my life is behind me."

To say as much is a measure of how deeply these poems come to terms with the joys and anguishes of even the most fortunate life. Waking to My Name is a book of coming to terms I with who as lover, husband, son to dying and father to forthcoming generations the poet has become. Pack's finest poems are, in the root sense of the word, domestic: they belong to the house; they are the structure the poet has built to define his place among (as Robert Frost would say) "the infinities." The strength of Pack's poems lies, more and

more surely, in the very limits that are some-times their manifest subjects: They penetratingly acknowledge how mortality, transcience, and diminishment of the passions can, and do, counter the spirit's continual wish for transcendence. As befits a poet who knew to title his first book The Irony of Joy, these poems inhabit illimitable paradox. In elegizing all that is lost to, and through, a lifetime, they celebrate the surviving moments out of which they are (literally) composed. These poems value life for what it is as well as what it might be; the poet makes of it what he can, he writes not least to compose himself. Even the title Waking to My Name ironically acknowledges how late a man comes to such earned self- recognition.

In their predominantly iambic movement, and in their structured forms, Pack's poems conserve the traditions from which they derive: the great tradition of English verse as that tradition has descended to him through such American forebears as Robert Frost and Richard Wilbur. Disciplined, skilled, and graceful, the poems formally demonstrate the continuity Pack senses in all of life's varied processes. His least quatrain handsomely argues for his implicit belief that life not only has meaning but has measurable meaning. And so it clearly does, in such typically multigenerational poems as "The Farm," or in his recognition that even as a man and a woman "have risen together/ for thirteen years" in a house that "inhales, reposes,/ We are what we will be." Even as people may "end up repeating what they are," the poet invents consolations against such stasis; the various tones of his poems are often trial runs: ways of feeling his way toward, as well as naming, new ways of inhabiting his own life.

The "I" of any poem is always partially a fiction, derived from the intelligence and emotion of the poet's own experience. In his prefatory "Note to the Reader," Pack rightfully reminds any reader that even the poet, for all the emotion he brings to his work, "must let the poem find its own way... as if it had a life of its own beyond him." The finest of these new poems of Pack have just that life. That he has, as he says, "revised repeatedly over the years" is only a measure to how continuingly he has seen and reseen his own experience. Waking to MyName goes beyond Pack's earlier vision in presenting the arc of a career and the curve of a life. It is book that deserves honor, not least for its grace in knowing and saying that

The grace of speech lives when we askforgiveness, knowing whatwe left unsaid.

Philip Booth, poet and teacher, is readingproofs of his sixth book of poems, which will bepublished later this year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Animal and The Hypermasculine Myth

September 1980 By Leonard L. Glass -

Feature

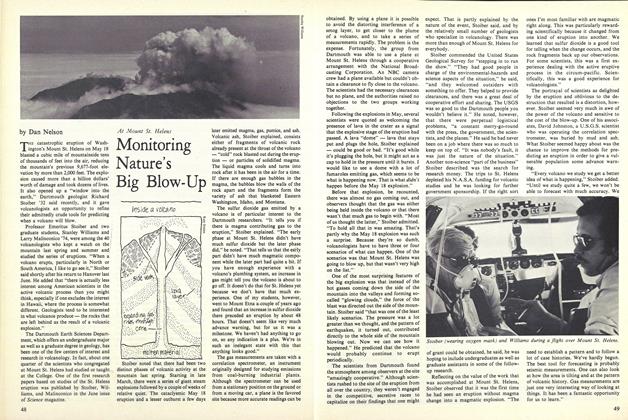

FeatureMonitoring Nature's Big Blow-Up

September 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

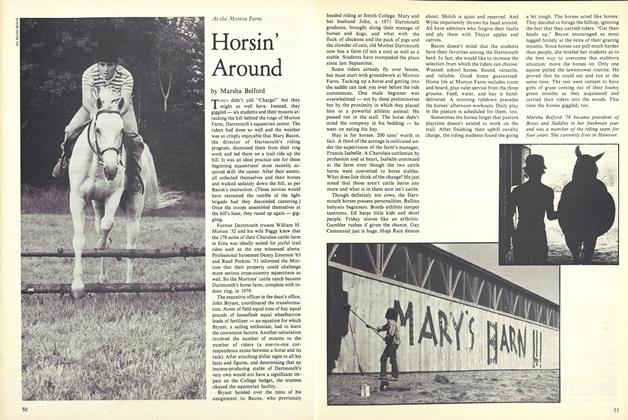

Cover StoryHorsin' Around

September 1980 By Marsha Belford -

Article

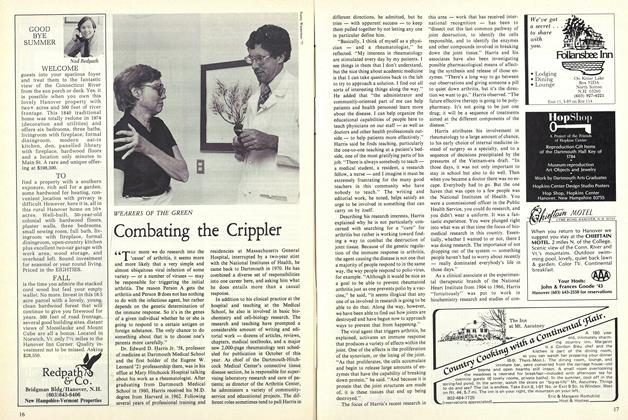

ArticleCombating the Crippler

September 1980 By D.M.N. -

Article

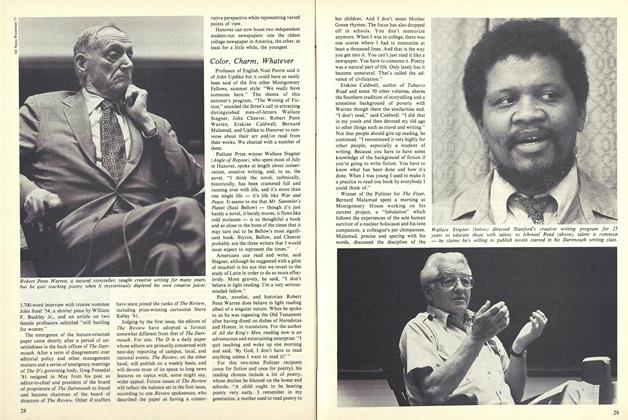

ArticleColor, Charm, Whatever

September 1980 -

Article

ArticleSteel Elected

September 1980

Philip Booth '47

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

January 1954 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

March 1957 -

Article

ArticleAllan Macdonald

January 1952 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Article

ArticlePreoccupation: Poetry

MARCH 1959 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Books

BooksTHIRTY-FIVE DARTMOUTH POEMS.

JANUARY 1964 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Books

BooksA Philosophical Poet, Full Of Wonder

April 1977 By PHILIP BOOTH '47

Books

-

Books

BooksDEMOCRATIC GOVERNMENTS IN EUROPE:

October 1936 By A. H. Basye -

Books

BooksTHE HAND IN THE PICTURE,

November 1947 By Eric P., THEODORE KARWOSKI -

Books

BooksOUTPOSTS OF THE PUBLIC SCHOOL

April 1939 By Highly Recommended, Louis P. Benezet '99 -

Books

BooksSAMUEL BECKETT: POET AND CRITIC.

FEBRUARY 1971 By J. D. O'HARA '53 -

Books

BooksTHIS THING CALLED FREEDOM.

DECEMBER 1970 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE CIVILIAN AND THE MILITARY.

July 1956 By LEWIS D. STILWELL