On recruiting

RECRUITING isn't something only coaches do. The number of Dartmouth students, football players or flautists, who weren't recruited is probably small. Somebody — an admissions officer, : a teacher, an alumni club enrollment worker, a neighbor, or a relative — probably suggested "You ought to consider applying to Dartmouth."

But for some reason people are more interested in, or more defensive about, the recruiting of student athletes than they are about the enrollment of student actors, debaters, musicians, artists, and chess players. Maybe it is the same reason that makes the comings and goings of coaches inspire more attention than the hirings and firings of professors. It could also have something to do with the probability that losing a five-foot eight-inch 150-pound math major to Yale won't threaten the outcome of a football game in the same way that losing a six-foot four-inch 250-pound tackle will. Perhaps it reflects the fact that, say, the Romance Languages Department doesn't have a recruiting budget and the Athletic Department does. Then, possibly, it could be only an over-reaction to rumors of Neanderthals on another team's starting line-up or to stories about new cars given to husky freshmen at some mid-western powerhouse.

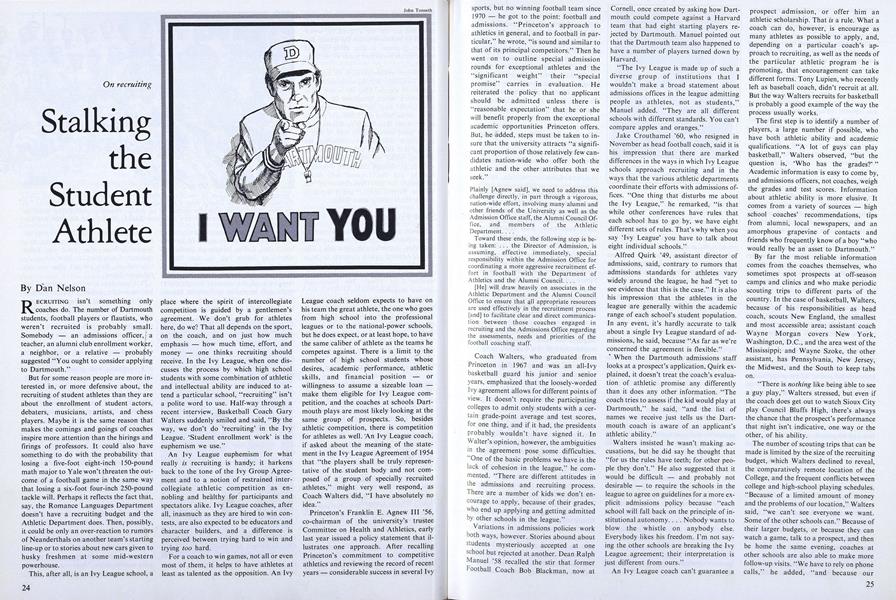

This, after all, is an Ivy League school, a place where the spirit of intercollegiate competition is guided by a gentlemen's agreement. We don't grub for athletes here, do we? That all depends on the sport, on the coach, and on just how much emphasis — how much time, effort, and money — one thinks recruiting should receive. In the Ivy League, when one discusses the process by which high school students with some combination of athletic and intellectual ability are induced to attend a particular school, "recruiting" isn't a polite word to use. Half-way through a recent interview, Basketball Coach Gary Walters suddenly smiled and said, "By the way, we don't do 'recruiting' in the Ivy League. 'Student enrollment work' is the euphemism we use."

An Ivy League euphemism for what really is recruiting is handy; it harkens back to the tone of the Ivy Group Agreement and to a notion of restrained intercollegiate athletic competition as ennobling and healthy for participants and spectators alike. Ivy League coaches, after all, inasmuch as they are hired to win contests, are also expected to be educators and character builders, and a difference is perceived between trying hard to win and trying too hard.

For a coach to win games, not all or even most of them, it helps to have athletes at least as talented as the opposition. An Ivy League coach seldom expects to have on his team the great athlete, the one who goes from high school into the professional leagues or to the national-power schools, but he does expect, or at least hope, to have the same caliber of athlete as the teams he competes against. There is a limit to the number of high school students whose desires, academic performance, athletic skills, and financial position — or willingness to assume a sizeable loan — make them eligible for Ivy League competition, and the coaches at schools Dartmouth plays are most likely looking at the same group of prospects. So, besides athletic competition, there is competition for athletes as well. 'An Ivy League coach, if asked about the meaning of the statement in the Ivy League Agreement of 1954 that "the players shall be truly representative of the student body and not composed of a group of specially recruited athletes," might very well respond, as Coach Walters did, "I have absolutely no idea."

Princeton's Franklin E. Agnew III '56, co-chairman of the university's trustee Committee on Health and Athletics, early last year issued a policy statement that illustrates one approach. After recalling Princeton's commitment to competitive athletics and reviewing the record of recent years - considerable success in several Ivy sports, but no winning football team since 1970 — he got to the point: football and admissions. "Princeton's approach to athletics in general, and to football in particular," he wrote, "is sound and similar to that of its principal competitors." Then he went on to outline special admission rounds for exceptional athletes and the "significant weight" their "special promise" carries in evaluation. He reiterated the policy that no applicant should be admitted unless there is "reasonable expectation" that he or she will benefit properly from the exceptional academic opportunities Princeton offers. But, he added, steps must be taken to insure that the university attracts "a significant proportion of those relatively few candidates nation-wide who offer both the athletic and the other attributes that we seek."

Plainly [Agnew said], we need to address this challenge directly, in part through a vigorous, nation-wide effort, involving many alumni and other friends of the University as well as the Admission Office staff, the Alumni Council Office, and members of the Athletic Department. ...

Toward these ends, the following step is being taken: ... the Director of Admission, is assuming, effective immediately, special responsibility within the Admission Office for coordinating a more aggressive recruitment effort in football with the Department of Athletics and the Alumni Council....

[He] will draw heavily on associates in the Athletic Department and the Alumni Council Office to ensure that all appropriate resources are used effectively in the recruitment process [and] to facilitate clear and direct communication between those coaches engaged in recruiting and the Admissions Office regarding the assessments, needs and priorities of the football coaching staff.

Coach Walters, who graduated from Princeton in 1967 and was an all-Ivy basketball guard his junior and senior years, emphasized that the loosely-worded Ivy agreement allows for different points of view. It doesn't require the participating colleges to admit only students with a certain grade-point average and test scores, for one thing, and if it had, the presidents probably wouldn't have signed it. In Walter's opinion, however, the ambiguities in the agreement pose some difficulties. "One of the basic problems we have is the lack of cohesion in the league," he commented. "There are different attitudes in the admissions and recruiting process, There are a number of kids we don't encourage to apply, because of their grades, who end up applying and getting admitted by other schools in the league."

Variations in admissions policies work both ways, however. Stories abound about students mysteriously accepted at one school but rejected at another. Dean Ralph Manuel '58 recalled the stir that former football Coach Bob Blackman, now at Cornell, once created by asking how Dartmouth could compete against a Harvard team that had eight starting players rejected by Dartmouth. Manuel pointed out that the Dartmouth team also happened to have a number of players turned down by Harvard.

"The Ivy League is made up of such a diverse group of institutions that I wouldn't make a broad statement about admissions offices in the league admitting people as athletes, not as students," Manuel added. "They are all different schools with different standards. You can't compare apples and oranges."

Jake Crouthamel '60, who resigned in November as head football coach, said it is his impression that there are marked differences in the ways in which Ivy League schools approach recruiting and in the ways that the various athletic departments coordinate their efforts with admissions offices. "One thing that disturbs me about the Ivy League," he remarked, "is that while other conferences have rules that each school has to go by, we have eight different sets of rules. That's why when you say 'lvy League' you have to talk about eight individual schools."

Alfred Quirk '49, assistant director of admissions, said, contrary to rumors that admissions standards for athletes vary widely around the league, he had "yet to see evidence that this is the case." It is also his impression that the athletes in the league are generally within the academic range of each school's student population. In any event, it's hardly accurate to talk about a single Ivy League standard of admissions, he said, because "As far as we're concerned the agreement is flexible."

When the Dartmouth admissions staff looks at a prospect's application, Quirk explained, it doesn't treat the coach's evaluation of athletic promise any differently than it does any other information. "The coach tries to assess if the kid would play at Dartmouth," he said, "and the list of names we receive just tells us the Dartmouth coach is aware of an applicant's athletic ability."

Walters insisted he wasn't making accusations, but he did say he thought that "for us the rules have teeth; for other people they don't." He also suggested that it would be difficult — and probably not desirable — to require the schools in the league to agree on guidelines for a more explicit admissions policy because "each school will fall back on the principle of institutional autonomy.... Nobody wants to blow the whistle on anybody else. Everybody likes his freedom. I'm not saying the other schools are breaking the Ivy League agreement; their interpretation is just different from ours."

An Ivy League coach can't guarantee a prospect admission, or offer him an athletic scholarship. That is a rule. What a coach can do, however, is encourage as many athletes as possible to apply, and, depending on a particular coach's approach to recruiting, as well as the needs of the particular athletic program he is promoting, that encouragement can take different forms. Tony Lupien, who recently left as baseball coach, didn't recruit at all. But the way Walters recruits for basketball is probably a good example of the way the process usually works.

The first step is to identify a number of players, a large number if possible, who have both athletic ability and academic qualifications. "A lot of guys can play basketball," Walters observed, "but the question is, 'Who has the grades?' " Academic information is easy to come by, and admissions officers, not coaches, weigh the grades and test scores. Information about athletic ability is more elusive. It comes from a variety of sources — high school coaches' recommendations, tips from alumni, local newspapers, and an amorphous grapevine of contacts and friends who frequently know of a boy "who would really be an asset to Dartmouth."

By far the most reliable information comes from the coaches themselves, who sometimes spot prospects at off-season camps and clinics and who make periodic scouting trips to different parts of the country. In the case of basketball, Walters, because of his responsibilities as head coach, scouts New England, the smallest and most accessible area; assistant coach Wayne Morgan covers New York, Washington, D.C., and the area west of the Mississippi; and Wayne Szoke, the other assistant, has Pennsylvania, New Jersey, the Midwest, and the South to keep tabs on.

"There is nothing like being able to see a guy play," Walters stressed, but even if the coach does get out to watch Sioux City play Council Bluffs High, there's always the chance that the prospect's performance that night isn't indicative, one way or the other, of his ability.

The number of scouting trips that can be made is limited by the size of the recruiting budget, which Walters declined to reveal, the comparatively remote location of the College, and the frequent conflicts between college and high-school playing schedules. "Because of a limited amount of money and the problems of our location," Walters said, "we can't see everyone we want. Some of the other schools can." Because of their larger budgets, or because they can watch a game, talk to a prospect, and then be home the same evening, coaches at other schools are also able to make more follow-up visits. "We have to rely on phone calls," he added, "and because our recruiting budget isn't necessarily increasing every year, and because of inflation, we have to do more with our money. It's a real problem."

Comparing one budget to another is to some extent misleading because a school far from urban areas has to send a coach further to watch the top high school athletes in action. For what it's worth, however, the 1976 recruiting budget for basketball at the University of Pennsylvania, in the heart of basketball country, was reported in Penn's alumni magazine by staff writer Marshall Ledger, Dartmouth '61, as $10,000 — compared to $33,000 for football. (The recruiting budget for all sports at Penn was reported as $59,575. In 1973-74, the last year figures were available, Dartmouth's total athletic enrollment budget was $110,000. Shortly afterward, the Ivy League schools agreed to each take a ten per cent reduction in their recruiting budgets and freeze them.)

As a result of the size of his budget, Walters said he has to deal with as many players as he can find, and the way he fills the notebooks in his office with names is to send out letters in the spring soliciting information from high-school coaches. Most, if not all, of the Dartmouth coaches send out similar letters and Drew Tallman, Athletic Department business manager and liason to the Admissions Office, estimated that the return on the letters is 10 to 20 per cent. Walters noted, though, that because of the reputation of Ivy League basketball, it isn't always the names of the best players that he receives.

Once Walters has the name of a prospect, he sends him a letter which says, in essence, we're interested in you — if you're interested in Dartmouth and you think you qualify for admission, fill out the enclosed card and we'll have an application sent to you. If a coach is particularly interested in a player, there will probably be one or more phone calls made, the student will perhaps be contacted by a local alumnus, and a coach might make a visit to watch the prospect play and to talk with him and his parents about Dartmouth.

When the cards come in, the Athletic Department's enrollment secretary makes copies for the coach and the Admission Office, which then sends the student application forms. The information supplied by the prospects is also recorded on two computer programs, according to Tallman, one belonging to the Athletic Department and one belonging to the Admissions Office. Although neither office has access to the other's computer file, the programs are coordinated to the extent that the coaches can find out if the student has filed an application and admissions officers can find out how the coach has ranked the candidate's athletic potential. The coaches and admissions officers also hold one or more meetings in the spring.

"Recruiting in the Ivy League is done in stages," Walters summarized. "The first job is to get the kid to apply. Then you work on the prospect until he finds he can get in. Finally, if he gets in, you have about two weeks to wrap him up. The first stage is the most difficult, but at each stage it is progressively more difficult to keep the kid interested, particularly if full-athletic-scholarship schools are interested in him. Some of those schools are at his games every time he plays. We have to rely on calls. Then, maybe someone you've recruited won't get in."

Phone calls aren't a coach's only means of "wrapping up" a prospect. The alumni Sponsors Program, originated by Bob Blackman and run for the past 16 years by Larry Leavitt '25, has proved so effective that Athletic Director Seaver Peters '54 recently suggested to class newsletter editors that they might want to describe the program to their classmates.

Under NCAA and Ivy League rules, an alumnus may contribute the cost of a prospect's transportation to and from the College. The prospect is able to talk to the coach and spend a weekend getting acquainted with the school. A sponsor can choose, if he wants, which sport he would like to help and from which geographic location he'd like to sponsor a prospect — whether he would like to contribute toward the cost of a round-trip or one-way ticket from New York, for instance, or San Francisco. The contribution is tax-deductible, currently counts toward the Campaign for Dartmouth, and is eligible for some corporate matching-gifts programs. The College shows its appreciation by giving sponsors preferred seating at football games or other events.

Leavitt, former headmaster of Vermont Academy, volunteers a considerable amount of time each week coordinating his efforts with the Athletic Department, matching sponsors with prospects, keeping track of the money and the plane tickets, and attending to the correspondence involved. The program, he said, often attracts athletes who would otherwise never have considered Dartmouth and who couldn't afford to visit here on their own resources, and it has the added benefit of stimulating alumni interest in the College and generating some rewarding friendships between students and alumni.

Participation in the program has increased notably over the past several years, along with the cost of airplane tickets, Leavitt reported. From 1963, when there were 31 sponsors for football and 21 prospects flown in, to late 1977, the number of sponsors had grown to 210. Last year, 102 prospects were brought to the campus, at a cost of $18,070. The program concentrated entirely on football, with the exception of one swimmer brought here in 1965, until 1969, when the first track, hockey, and basketball players were sent airplane tickets. Swimming, lacrosse, and soccer joined the group the following year.

"It is gratifying to note that of the men on the sponsors list in 1963," he added, "there are at least 11 still supporting the program." Leavitt also noted that the venture has been so successful that former Dartmouth coaches and assistants have taken the idea with them to other schools.

An effort is made to match the prospect up with a congenial student host, who will shepherd the visitor around the campus, maybe take him to a fraternity party, and answer the inevitable questions about the coach, the team, the College, and the academic schedule. For a high school student who has perhaps, never been on a plane before, the weekend of courtship at Dartmouth — or at the other colleges he might visit — can play a large part in the decision he makes. (Things can backfire, too. There is a story about a much-sought-after recruit who went out for pizza with a group of Dartmouth students. No one had any money, it turned out, and he ended up buying the meal.) In his article about recruiting at Pennsylvania, Marshall Ledger recounted a conversation with two high school football players visiting the campus there:

"We talk about other schools they have seen. 'Yale was pretty identical to Penn,' Chuck says, 'but seemed run down. I was awful surprised. When we went by, someone said, "This is Yale." I said, "You gotta be kidding me." Whuh! I couldn't believe it.' Dartmouth scared him, there were so many recruits. 'I said uh-uh. No way. This is too big time. I was totally shocked. I thought I'd head for a smaller school.' "

Gary Walters said that when he talks to prospects he sells the "mystique" of Dartmouth. "We stress our ability to place people in the best graduate and professional schools. Whatever the kid wants to do can be enhanced by attending Dartmouth." The flexibility of the College's academic schedule — the opportunity for staggered terms off and for language-study abroad, for example — is also a selling point, although a coach is seldom happy to see an important player decide to spend his junior year in France.

Former varsity basketball player Bill Hooper '77, who like many alumni does some informal recruiting, said that when he talks to high school students he stresses "some of the non-basketball aspects of an education at Dartmouth" and tells a prospect that "at Dartmouth he won't be just another basketball player" because of the other opportunities available to students. Hooper also said that many athletes find the Dartmouth schedule of three courses per term more attractive than the five-course-per-semester schedule many other schools have. Impressed by Walters' style of coaching, which he described as "just as much an educational experience as a basketball experience," Hooper acknowledged that "the basketball program can't sell itself,"

Sophomore David Broil, a guard on this year's team who thought, seriously about going to Yale, his father's school, said that it was a combination of the impression Walters made on him, the rural location of the school, and the educational opportunities — not so much the reputation of the basketball program — that sold him on the College. When he decided to come to Dartmouth, Broil reflected, "the team was in a building situation. Because of the number of guards who would be graduating, it looked like I'd have a good chance to play. Walters' honesty really showed through. For basketball, what can he say, really? We're not going to be national champs."

financing a Dartmouth education is a problem for a number of recruits, and the specter of long-term indebtedness scares many of them away. In Walters' opinion, for many people, particularly those on financial aid, the size of the loan which must be assumed is reaching the pain level. ... We tell the kid that although he might have to make financial sacrifices in the short run, the sacrifices can be seen as an investment in the future because of the great education he can receive at Dartmouth. Kids from the Midwest, in particular, have an image of the Ivy League being a bastion of snobbery, of the elite. We tell them about all the people on financial aid, the people from different parts of the country."

Hockey Coach George Crowe, who finds that recruiting requires over half of his time, says that the high cost of coming to a school like Dartmouth has an effect on the number of players from middle-class families who apply. "I try to let them know where they'll be in 10 or 15 years, although it's almost impossible'to compete with scholarship schools for the top kids," he said. "As a result, we have to deal in numbers. If we had full scholarships it would be different." Al Quirk, in the Admissions Office, thinks that with few exceptions Ivy League schools are not even competing with scholarship schools for players. "It's a tough decision for a student and family to make to come to a place like Dartmouth where it might cost $4,000 more per year than it would where a kid can get both a good education and a ride," he noted.

The pressure is heavy on coaches who have to cull a crop of competitive starters from a student pool reduced in size by both academic standards and educational costs. Jake Crouthamel said that "a lot of college coaches have gone back to high schools or on. to the pros because of recruiting. It's not recruiting itself that's so bad, but what it entails. In something like Big-Ten recruiting, for example, is where it gets repugnant. It's not to that extent on our level. I find enjoyment in going out and selling a quality product I believe in. I believe I'm helping, not pressuring, the student.

"Even so, you get into situations where there are various pressures brought to bear on a young man which cloud the issue — pressures from family, friends, other schools, community businessmen — all sorts of things. You end up having to attack those pressures one by one. It gets discouraging. Over the years you get so you can recognize the kind of kid who would really fit in here, who would really be happy to be here. Then you hear the kinds of things he's been told about this school, or other schools, and it becomes very frustrating. The kid is pressured to go some place and he isn't happy. Yes, you could say that it sometimes happens that the kid's welfare is sacrificed in order to obtain his playing ability."

Former Baseball Coach Tony Lupien refused to recruit and relied on what he said was once a "distinctive style of education" to attract baseball players to Dartmouth. "That style was extremely appealing to the competitive team athlete," he stated, "and once the style was changed I don't think it was possible to bring in athletes of any stature at all." The athletes Dartmouth does attract, he observed, "are like half-baked potatoes; not good enough to eat but too good to throw away."

"If you're going to have an Ivy agreement, fine," he stated. "You can play the Ivy schools and then play schools like Middlebury and Bowdoin. But don't start thinking about playing a national schedule. You can't do it. If you want to attract athletes again, you have to either change the schedule so you can win some games by playing within your team's ability, or you have to cut the cost of the educational package. ... You have to ask, 'What are we doing to the boy?' The boy is the most important part of this whole thing and the boy has got to have a chance to play at a level where he is. This to me is a primary tenet of athletics."

What has happened, Lupien believes, is that institutional change and rising costs have forced team sports, and baseball in particular, to rely on "an extremely limited pool of available people for this socio-economic style of education," and that "the people here are pricing themselves out of competitive team athletics," attracting instead upper-class players of the individual sports — tennis, squash, skiing, and golf, for example. Team players wanting to attend an Ivy League college frequently choose one within commuting distance of home in order to save money.

"To justify the expense of an education here to a lower or middle-class family," he continued, "you have to lie and tell halftruths. What can I tell a boy, in truth, to make him come here? I'm going to have to lie to him and that's not a palatable situation. When you start making promises you can't deliver on, you compromise your relationship with players." Lupien, who graduated from Harvard in 1939, maintains that "encouraging people to come to a school is a natural function of alumni. Otherwise, you have pimps on the road. You have coaches here one year selling the school and then the next year they're somewhere else saying the same things. It's a whore's business."

In a 1976 interview with The Dartmouth, shortly after his proposal to do away with the losing baseball team's annual spring trip had been rejected by the Athletic Council, Lupien declared, "to shill for a school is a little beneath my dignity. I'm saying here is a school that has existed since 1769, and they don't need a man to come in and say, 'Will you please come to Dartmouth, we'll do this for you, we'll do that for you.' There's no such thing as a dignified recruiting approach. Sooner or later somebody has to prostitute themselves or they have to make a promise or say something which is going to influence the boy from going to the other place. I am very counter-recruiting, because I don't believe it's an ethical proposition."

James T. Brown '73, captain of the basketball team his senior year and holder of the most-valuable-player award and of field-goal and scoring records, an all-Ivy selection, and also former treasurer of his Class, said recently that he is still waiting for the fulfillment of some promises that were made to him when he was a high school senior. As a New York City ail- American, he said, he received over 250 scholarship offers but was persuaded to come to Dartmouth by several alumni and by former Coach Dave Gavitt '59. They promised, according to Brown "the advantage of 'Dartmouth resources' — particularly alumni resources — and emphasized the future benefits of a Dartmouth education. They talked about more than the basketball program, while other schools emphasized being a star at the school and the possibilities of a pro career."

Brown is currently unemployed. He left a coaching position at Columbia in order to try to launch a public-relations and sports-equipment promotion venture with former teammate William Raynor '74, also a team captain during his senior year and, like Brown, presently unemployed.

Brown feels disappointed they haven't had any luck in obtaining sponsorship for their venture, or in making contacts with sporting-goods manufacturers, although contact with helpful alumni who would be interested in his future career is one of the things Brown said he was led to expect as a graduate of the College. "We were offered the resources of the 'great alumni body,' " he recalled. "This is an attempt to find out if those resources we were told about exist. We're trying to make a transition. We don't want people to say, 'this is just another jock.' I'm asking if this was just a school which afforded me a chance to play basketball, something other schools might have done more successfully."

Bill Hooper, who knows Brown, said he could understand his dissatisfaction and observed that there are probably other recent alumni with a similar point of view. "Brown and Raynor played when Dartmouth basketball was at a low ebb and when there was a lack of continuity in the coaching staff," Hooper added. "Dartmouth is not an easy place for a black or an urban kid to adjust to, and there were some kids who went here and expected things to be done for them — who expected jobs to materialize when they got out. It's possible they were led to expect that, although there are also a number of examples the other way. It's a matter of attitude, and the attitude a player develops is partially a reflection on the coaching he receives. Walters emphasizes a commitment to the group — a cooperative effort — and that shows in his players' attitudes."

Dave Gavitt, who recruited Brown but left Dartmouth in 1969 and is now coaching at Providence, said that as he remembers 50 or 60 schools were actively recruiting Brown, although Dartmouth was the only Ivy League school seriously interested in him, and that it was primarily the influence of his high-school coach that persuaded him to come here.

Gavitt said that the camaraderie of Dartmouth alumni was always one of the things he emphasized when he talked to prospects. "We used to point to a very unique spirit in the alumni body and to the fact that Dartmouth men around the world tend to seek each other out. We never said that coming to Dartmouth will take care of the rest of your life," he noted, "but we did say that it will help to open doors for you.

"It's hypocritical to say that Ivy League schools don't recruit athletes," Gavitt claimed, "although what they recruit are student-athletes." He observed that recruiting within the league used to be only a minor part of a coach's job — he would send out a few letters, make some phone calls, and leave it at that. Now it's a "numbers game," and the increased tempo probably started with Dartmouth football where, with mass mailings, recruiting became "organized and computerized."

Athletic Director Seaver Peters emphasized the positive side of recruiting. Peters, Dean Manuel, Coach Walters, and Bill Hooper all pointed to former basketball player Adam Sutton '76 as one example of a number of outstanding athletes who were recruited to play at Dartmouth, benefited from their experience here, and were able to take advantage of alumni contacts to begin promising careers. "Sutton really came from zero" as far as his attitude was concerned, Peters said, explaining that he had a "real turnaround" after his sophomore year, landed a job at a prestigious Chicago bank after graduation, and is also studying for a graduate degree. According to Peters, "there are a lot more Suttons" than there are negative examples.

Peters also referred to the "very real consistency" between athletic recruiting at Dartmouth and the College's overall enrollment effort to attract top candidates with special talents. He cited the example of the number of football recruits who graduate with academic honors. In the Class of 1977, according to a tally taken by Jake Crouthamel, of all the men recruited to some extent by football, 35 graduated cum laude or higher, four were Phi Beta Kappa, 31 earned special distinction in their majors, and one was a senior fellow.

"I have no hesitation in saying we recruit as hard as we can within the restrictions," Peters declared. "Our coaches sell an accurate and positive image of Dartmouth College, a product they believe in and love, instead of criticizing other schools. We also sell the fact that if you're eligible for financial aid, you don't have to continue playing a sport in order to receive it. A coach can't get away with being dishonest. I'm convinced we can and do take a dignified approach to recruiting. The overall effect of the effort is a plus for the institution as well as for its graduates."

Gavitt and the other coaches interviewed agree that there is little chance that the recruiting pace will diminish. Agnes Kurtz, assistant director of athletics at Dartmouth, said that some coaches of women's teams elsewhere are pushing for a change in the AIAW (Association for Intercollegiate Athletics For Women) rule prohibiting them from recruiting female students in person. They presently may scout, write letters, and make phone calls, but may not approach a student at her home or high school. "Everyone who is in recruiting hates it," according to Kurtz. "It wastes a lot of time and it's expensive. You put a lot of effort into tracking people down and encouraging them to apply. If 20 apply, maybe ten are accepted and maybe two or three decide to come.... It would be good if everyone would agree not to recruit, but there's no way out for the men's teams. If we stopped recruiting and Yale didn't, how would we beat them?"

Even if there was an agreement to limit recruiting, which Gavitt thinks highly improbable, the coach of a losing team would soon be pressured into looking around on the sly for the athletes he needed. And Gavitt doesn't think it is at all likely that a single coach would decide not to recruit. "Recruiting is the worst part of my job," he concluded, "and it's a bad idea for anyone. But if you don't recruit you lose, and if you lose, sooner or later you get fired."

John Tonseth

Gary Walters: 'For us the rules haveteeth, for other people they don't.'

Tony Lupien: 'There's no such thing asa dignified recruiting approach.'

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

March 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureNEFERTITI

March 1978 By Ray W. Smith -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

March 1978 -

Article

ArticleAn Untraditional Path

March 1978 By A.E.B. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

March 1978 By R.H.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1978 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR.

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

FeatureGod and Man at Dartmouth

March 1976 By DAN NELSON -

Article

ArticleA Journey: Five days to Big Rapids

September 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

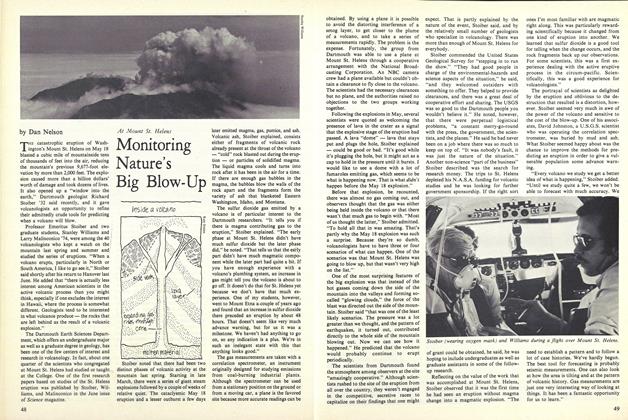

FeatureMonitoring Nature's Big Blow-Up

September 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

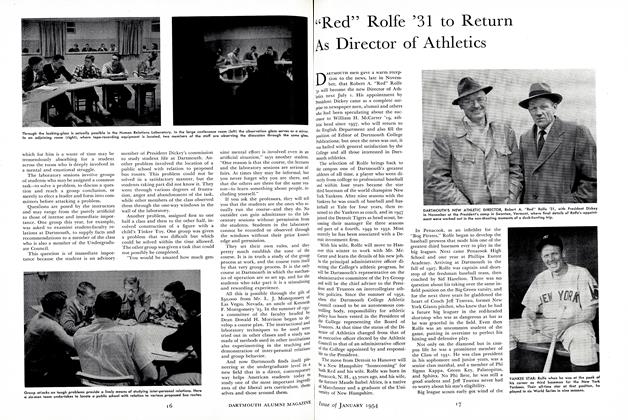

Feature"Red" Rolfe '31 to Return As Director of Athletics

January 1954 By C.E.W. -

FEATURES

FEATURESThe Matchmakers

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO LIVE A MORE MEANINGFUL LIFE AND DIE HAPPY

Jan/Feb 2009 By KUL GAUTAM '72 -

Feature

FeatureMusic

MAY 1957 By PROF. JAMES A. SYKES -

Feature

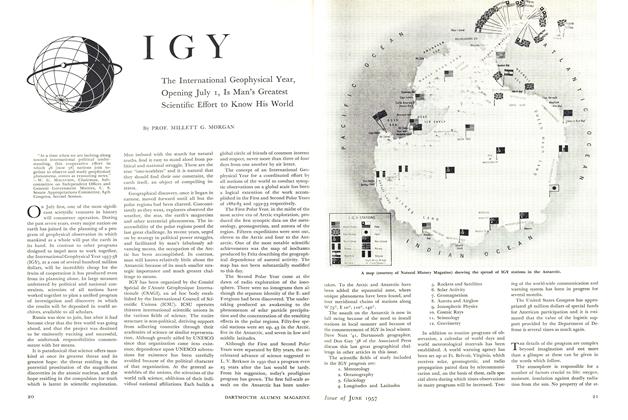

FeatureIGY

June 1957 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Lesson Tabled

MARCH 1995 By Ursula Gibson '76