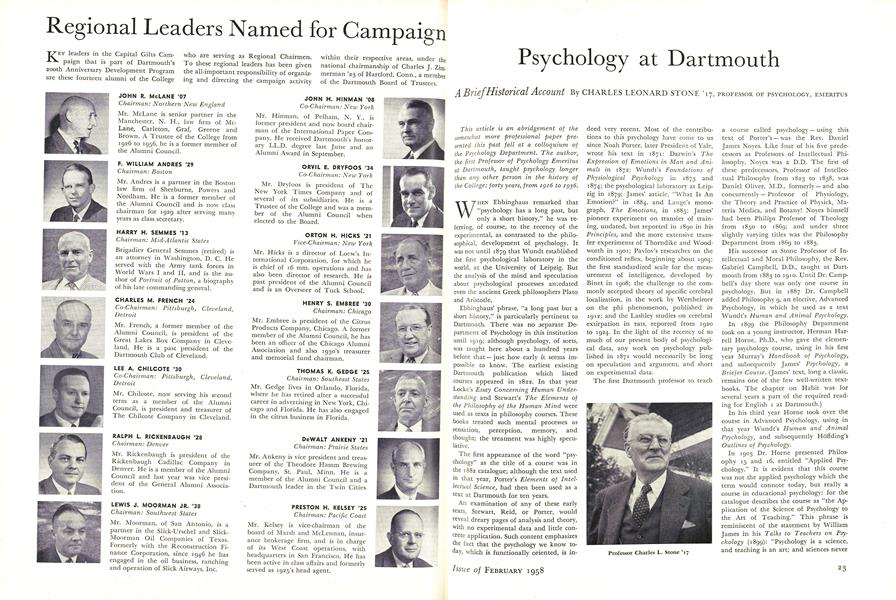

This article is an abridgement of thesomewhat more professional paper presented this past fall at a colloquium ofthe Psychology Department. The author,the first Professor of Psychology Emeritusat Dartmouth, taught psychology longerthan any other person in the history ofthe College: forty years, from 1916 to 1956.

A Brief Historical Account

PROFESSOR OF PSYCHOLOGY, EMERITUS

WHEN Ebbinghaus remarked that "psychology has a long past, but only a short history," he was referring, of course, to the recency of the experimental, as contrasted to the philosophical, development of psychology. It was not until 1879 that Wundt established the first psychological laboratory in the world, at the University of Leipzig. But the analysis of the mind and speculation about psychological processes antedated even the ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle.

Ebbinghaus' phrase, "a long past but a short history," is particularly pertinent to Dartmouth. There was no separate Department of Psychology in this institution until 1919; although psychology, of sorts, was taught here about a hundred years before that - just how early it seems impossible to know. The earliest existing Dartmouth publication which listed courses appeared in 1822. In that year Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding and Stewart's' The Elements ofthe Philosophy of the Human Mind were used as texts in philosophy courses. These books treated such mental processes as sensation, perception, memory, and thought; the treatment was highly speculative.

The first appearance of the word "psychology" as the title of a course was in the 1882 catalogue; although the text used in that year, Porter's Elements of Intellectual Science, had then been used as a text at Dartmouth for ten years.

An examination of any of these early texts, Stewart, Reid, or Porter, would reveal dreary pages of analysis and theory, with no experimental data and little concrete application. Such content emphasizes the fact that the psychology we know today, which is functionally oriented, is indeed very recent. Most of the contributions to this psychology have come to us since Noah Porter, later President of Yale, wrote his text in 1871: Darwin's TheExpression of Emotions in Man and Animals in 1872; Wundt's Foundations ofPhysiological Psychology in 1873 and 1874; the psychological laboratory at Leipzig in 1879; James' article, "What Is An Emotion?" in 1884, and Lange's monograph, The Emotions, in 1885; James' pioneer experiment on transfer of training, undated, but reported in 1890 in his Principles, and the more extensive transfer experiments of Thorndike and Woodworth in 1901; Pavlov's researches on the conditioned reflex, beginning about 1904; the first standardized scale for the measurement of intelligence, developed by Binet in 1908; the challenge to the commonly accepted theory of specific cerebral localization, in the work by Wertheimer on the phi phenomenon, published in 1912; and the Lashley studies on cerebral extirpation in rats, reported from 1920 to 1924. In the light of the recency of so much of our present body of psychological data, any work on psychology published in 1871 would necessarily be long on speculation and argument, and short on experimental data.

The first Dartmouth professor to teach a course called psychology - using this text of Porter's - was the Rev. Daniel James Noyes. Like four of his five predecessors as Professors of Intellectual Philosophy, Noyes was a D.D. The first of these predecessors, Professor of Intellectual Philosophy from 1823 to 1838, was Daniel Oliver, M.D., formerly — and also concurrently - Professor of Physiology, the Theory and Practice of Physick, Materia Medica, and Botany! Noyes himself had been Philips Professor of Theology from 1850 to 1869; and under three slightly varying titles was the Philosophy Department from 1869 to 1883.

His successor as Stone Professor of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy, the Rev. Gabriel Campbell, D.D., taught at Dartmouth from 1883 to 1910. Until Dr. Campbell's day there was only one course in psychology. But in 1887 Dr. Campbell added Philosophy 9, an elective, Advanced Psychology, in which he used as a text Wundt's Human and Animal Psychology.

In 1899 the Philosophy Department took on a young instructor, Herman Harrell Home, Ph.D., who gave the elementary psychology course, using in his first year Murray's Handbook of Psychology, and subsequently James' Psychology, aBriefer Course. (James' text, long a classic, remains one of the few well-written textbooks. The chapter on Habit was for several years a part of the required reading for English 1 at Dartmouth.)

In his third year Home took over the course in Advanced Psychology, using in that year Wundt's Human and AnimalPsychology, and subsequently Hoffding's Outlines of Psychology.

In 1903 Dr. Home presented Philosophy 15 and 16, entitled "Applied Psychology." It is evident that this course was not the applied psychology which the term would connote today, but really a course in educational psychology: for the catalogue describes the course as "the Application of the Science of Psychology to the Art of Teaching." This phrase is reminiscent of the statement by William James in his Talks to Teachers on Psychology (1899): "Psychology is a science, and teaching is an art; and sciences never generate arts directly out of themselves. An intermediary inventive mind must make the application, by using its originality." As James was the master psychologist in this country at the turn of the century, Dr. Horne no doubt in part developed his course description from this provocative book by James.

An alumnus, Professor Emeritus Leland Griggs, who was a student of Dr. Home's, recently referred to him as the best teacher in the College in his day. Apparently elementary psychology became very popular, because Dr. Horne had to have assistants for the latter part of his term at Dartmouth. I want to mention very briefly two of these assistants who became distinguished educators. Harry Woodburn Chase '04 went on to become President of the University of North Carolina and later Chancellor of New York University. Albert Richard Chandler '08 became an eminent professor of philosophy at Ohio State University, his chief interest being in esthetics.

When Dr. Home left Dartmouth to teach at New York University, his place in the Philosophy Department at Dartmouth was taken in 1909 by Dr. Wilmon Henry Sheldon, who for one year taught both the elementary and the advanced psychology courses. As Dr. Campbell retired in 1910, Dr. Sheldon no longer had to teach the "nasty little science." (This description is William James', after he had spent - years producing his monumental Principles of Psychology.) In 1910 Sheldon was relieved of the courses in psychology by Dr. Walter Van Dyke Bingham.

Until 1910 there had been only three or four courses offered in psychology, the elementary course, the advanced course, and one or two semesters of educational psychology. Assistant Professor Bingham was a vigorous person who not only established the psychology laboratory, but also taught seven courses, three of them in experimental psychology. In 1912 he dropped two courses, but added one entitled 'Mental Tests." (Only the year before, in 1911, had Goddard translated the Binet tests and restandardized them on American children.) In 1912 the second semester in introductory psychology was called "Applied Psychology." The course description read: "A more intensive study of emotion and impulse, habit-formation and voluntary action; together with the application of the psychology of these dynamic aspects of human nature to certain fields of practical activity, such as business, medicine, and law."

Bingham left Dartmouth in 1915 to become chairman of a very ambitious program of psychology at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. He became in this position and in later incumbencies nationally known as a champion of applied psychology, especially in the Army and in industry.

In 1915 Henry Thomas Moore, who in the previous year had received his doctorate at Harvard, with a thesis on "The Genetic Aspect of Consonance and Dissonance," came to Dartmouth as an Assistant Professpr. From him two later members of this Department, Professor Allen and I, received our initial instruction in psychology. After somewhat over a year in the Army, Moore returned to Dartmouth in 1919 as a full professor. At that time Psychology became an independent department.

In the spring of 1915 the Trustees of Dartmouth voted to separate Psychology and Education from Philosophy, to constitute the Department of Psychology and Education. In 1919 this joint department was divided into two separate departments. If the formal independence of Psychology at Dartmouth seems very recent, it is interesting to note that this independence was officially declared even later at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton: in 1920-21 at Princeton, in 1928 at Yale, and in 1934 at Harvard. In effect, however, psychology had a functional autonomy a decade or more before the formal independence.

Although Dartmouth preceded Harvard, Yale, and Princeton in attaining formal departmental independence for psychology, Dartmouth was notably tardy in establishing a psychology laboratory. Harvard and Yale instituted their laboratories in 1892: James the promoter, and Munsterberg the director at Harvard; Ladd the promoter, and Scripture the director at Yale. Under Mark Baldwin Princeton established its laboratory in the following year, 1893. But it was not until the coming of Walter Van Dyke Bingham, in 1910, that Dartmouth instituted its psychology laboratory. The first American laboratory was established in 1883 at Johns Hopkins by G. Stanley Hall, later President of Clark University. (Clark became a distinguished psychological center, producing such men as Goddard, Terman, and Gesell.) Most of the establishers of the early psychology laboratories in this country were, significantly, one-time students of Wundt at Leipzig - prominent among them Hall, Cattell, Munsterberg, Scripture, and Titchener.

In 1925, just as Moore was blossoming into a social psychologist, he resigned from Dartmouth to become a Professor in the School of Education at the University of Michigan. But before September he was induced to ask release from this appointment to become President of Skidmore College, a position he has filled with distinction for 32 years. Universally beloved by his students and the faculty, he retired in June 1957. In 1940 Henry Moore, always a friend of Dartmouth - his two sons are Dartmouth alumni - was awarded Dartmouth's honorary doctorate of laws.

Since 1925 psychologists have come and gone; courses have been added and dropped. If there has been any special departmental trend, I should say it has been in the social direction. Some of this emphasis is attributable to the influence of Henry Moore and Gordon Allport. (Allport was an Assistant Professor in this department from 1926 to 1930; is now professor of Psychology at Harvard; and was in 1939 President of the American Psychological Association.) But even more fully this social trend has been part of a general growing interest in men as men, in the increasing desire to understand the human factor in the world in which we live.

perhaps the recent contribution to the Dartmouth curriculum next most important to the Great Issues Course - both as a fresh educational venture and as a response to vital need - is the addition in 1952 of the two courses in Human Relations, Psychology-Sociology 37 and Psychology-Sociology 38. The motivation for these courses was surely the general demand for fuller knowledge about human nature and its modification, not in the abstract, but in the concrete, not in the isolated individual, but in his dynamic society.

Since Dartmouth's primary obligation, as stated by John Sloan Dickey, and as quoted in the Dartmouth catalogue, is "service to human society," it follows that the major responsibility of each of the departments of the College is "service to human society." It is appropriate, therefore, that psychology, which began at Dartmouth with the study of Locke's "Essay Concerning Human Understanding," should, after a subsequent period of nearly a century and a half, with its cumulative enrichment of experience and knowledge, once again become dedicated to human understanding.

Professor Charles L. Stone '17

Dartmouth's newest offering in psychology: the course in human relations.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Makes a College New?

February 1958 By BANCROFT H. BROWN, B. P., JOHN. NASH '60 -

Feature

FeatureFastest Man on Skis

February 1958 By BOB ALLEN '45 -

Feature

FeatureRegional Leaders Named for Campaign

February 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1958 By JOHN A. SAWYER, FRANK T. WESTON -

Article

ArticleThe Murder of Christie Warden

February 1958

CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17

-

Article

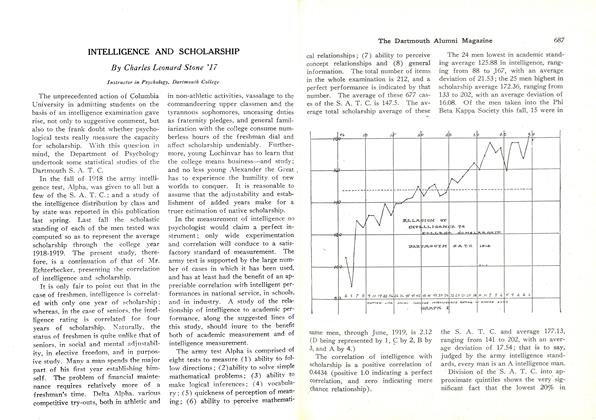

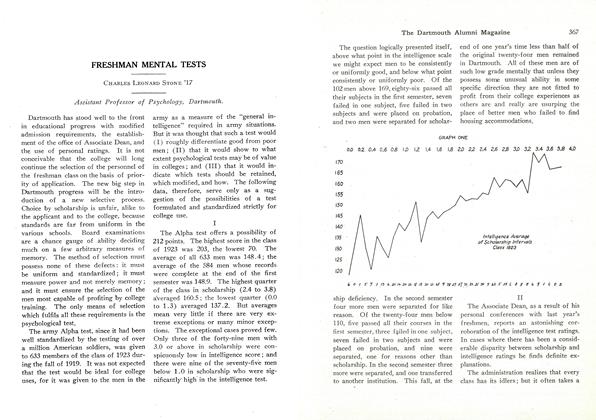

ArticleINTELLIGENCE AND SCHOLARSHIP

March 1920 By Charles Leonard Stone '17 -

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN MENTAL TESTS

April 1921 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Books

BooksFOUNDATIONS FOR AMERICAN EDUCATION

March 1948 By Charles Leonard Stone '17 -

Books

BooksTHE "WHY" OF MAN'S EXPERIENCE,

January 1951 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Article

ArticleEducation for What?

March 1953 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17

Features

-

Feature

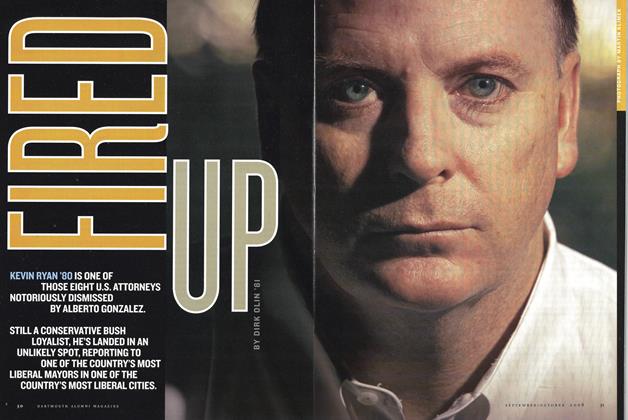

FeatureFired Up

Sept/Oct 2008 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

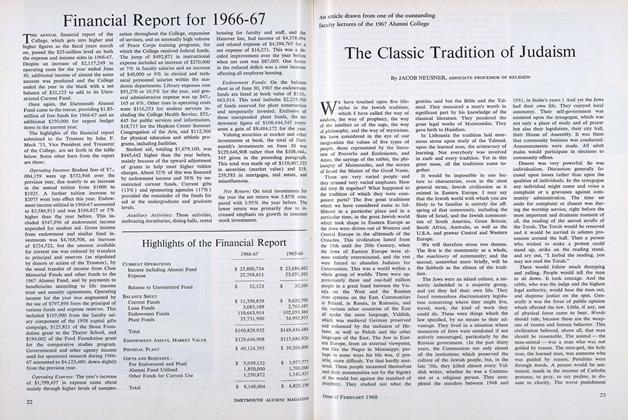

FeatureThe Classic Tradition of Judaism

FEBRUARY 1968 By JACOB NEUSNER -

Feature

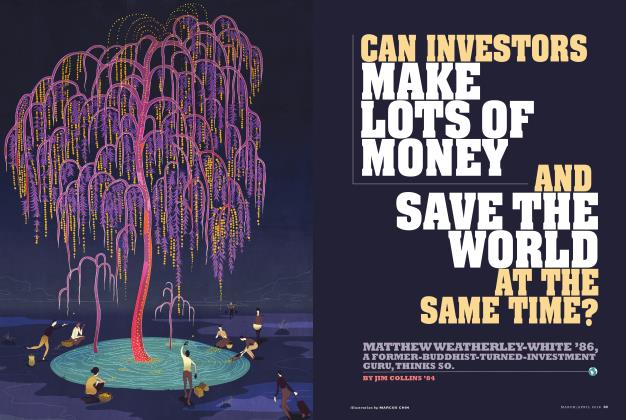

FeatureCan Investors Make Lots of Money and Save the World at the Same Time?

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May/June 2007 By Joe Novak '52 -

Feature

FeatureScotching the Myth About Alumni Sons

MAY 1967 By RAYMOND SOBEL, M.D. -

FEATURES

FEATURESThe Class of Covid-19

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13