DR. Tucker (My Generation, p. 280) spoke of himself and other Dartmouth presidents as standing in "The Wheelock Succession": and this fact he regarded as supremely important for the integrity not only of his office but of the College. "I believe that the greatest pos- session of the College has been and still is the spirit of Eleazar Wheelock."

In searching for words to express my understanding of the task of the William Jewett Tucker Foundation, I have gone back again and again to the situation in which this College was founded.

Time does not permit me to remind you of all those hopes and sacrifices which gave power to the motto which Eleazar Wheelock chose for the new college: VoxClamantis in Deserto.

We of the twentieth century have perhaps permitted ourselves to suppose that the motto suggested itself only because of the frontier character of colonial Hanover. It is true that conditions here were primitive, that it required an heroic faith to drive an old man to launch a precarious enterprise in the wilderness. In the physical sense, Wheelock, the missionary, sent his voice "crying in the wilderness."

May I ask: what did the voice in the wilderness cry?

Wheelock's deepest reason for suggesting this motto surely lay not simply in the physical situation of the new school but in the fact that its basic purpose was expressed in that cry. There can be no doubt that he wished for his undertaking that it might be a fitting response to that ancient summons: Vox Clamantis in Deserto:parate viam Domini! Isaiah 40:3. "The voice of one crying in the wilderness: Prepare ye the way of the Lord."

There is perhaps an explanation of the fact that today many people do not know what the crier cried. Today the College is related in a highly ambiguous way to the concept represented there. On the one hand, the College has never repudiated those aspects of its Charter which speak of "Christianizing the youth." Rather it has pointed with pride to this side of its heritage. On the other hand, the College as a matter of fact has abandoned any semblance of a "confessional" stance. What are we to say about this ambiguity? Can the cry, "Prepare ye the way of the Lord!" have any significance for us today? If so, will it be by virtue of a return to the older, frankly "confessional" position of the College?

I believe that precisely in this ambiguity lies our opportunity for what Dr. Tucker often referred to as "the larger mission of Christianity."

What would the attempt to return to confessional purity cost? If the cost were merely "scandal," that should hardly deter one who is serious about his faith. But I fear that it would cost our "relevance" - and in a way that is needless in our time.

The confessional task belongs to the Church. No doubt that task is not being performed perfectly; but it does not follow that it would be performed better because of the addition of one more institutional voice. However, there is a task which the College can and should do, a task which cannot be done so well, if at all, by the organized Church. This is the task of helping men from all conditions and backgrounds to experience the shock of self-knowledge. It is the Socratic task of helping men give birth to an understanding of or, perhaps better, a wonder about the human situation. It is the task of meeting men where they are, precisely in terms of their own traditions, aspirations and biases, and helping them to sense the spiritual depth of whatever commitments they have made — whether they have made them consciously or unconsciously. It is the task of bringing into the open the deeply human and profoundly moral question: who am I, and who ought I become?

Without this moral seriousness, no confession of faith is even heard, much less accepted. Without this seriousness preaching is, as someone has said, "giving answers to questions that were never asked."

If the College is to perform this human, Socratic function, it must be the arena of free and critical discussion. It must welcome the passions and the questions of all who are honestly concerned with the human drama in all its acts and scenes and lines.

Am I beyond my rights if I say that Dartmouth is committed to fostering "the shock of self-knowledge"? In any case, that is how I understand the mission of our College. You may say, but this is a "secular" mission. What has it to do with that grand old summons: "Prepare ye the way of the Lord"?

It is not the task of any man, even of the preacher, to produce faith in others. Christianity understands this to be the work of God - wherefore it is confessed that faith is a gift. It is our task as men to "prepare the way." In our day this means, first, to help men bring to light their fundamental and honest questions, so that whatever answer may be proposed by men, or given by God, may be truly heard and not simply classified as another interesting theoretical idea. Second, it means that men must have the opportunity for hearing, in depth and detail, the serious answers which have been given by other men throughout the ages.

In keeping with the cosmopolitan character of the campus, a character which is necessary to insure the honest and critical posing of questions, the College cannot enforce that one particular answer, one particular faith, be accepted by all. Men should hear the Gospel (or any alternative answer) freely, because impelled to hear by their own serious and honest questions.

It is fitting, therefore, that Dartmouth through her Chapel, witness to her own tradition, which invites men to wait expectantly for and then joyously to confess that Lord whose way the ancient prophet summoned us to prepare; and fitting also that Dartmouth not only through her Tucker Foundation but in all her life give expression to that ancient vocation which is laid upon all men of whatever creed: Know Thyself!

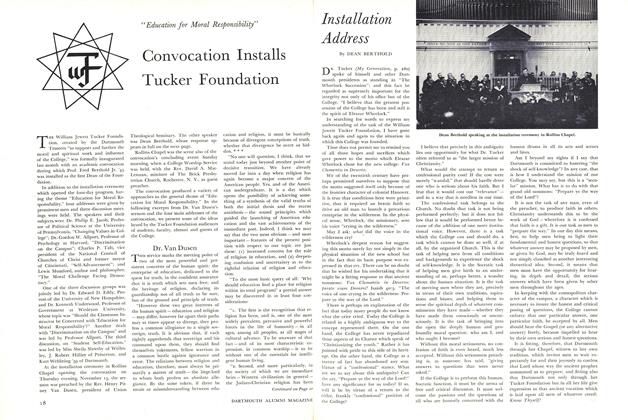

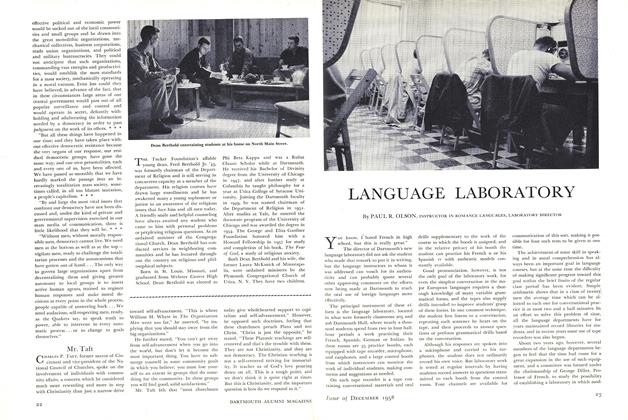

Dean Berthold speaking at the installation ceremony in Rollins Chapel,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureConvocation Installs Tucker Foundation

December 1958 -

Feature

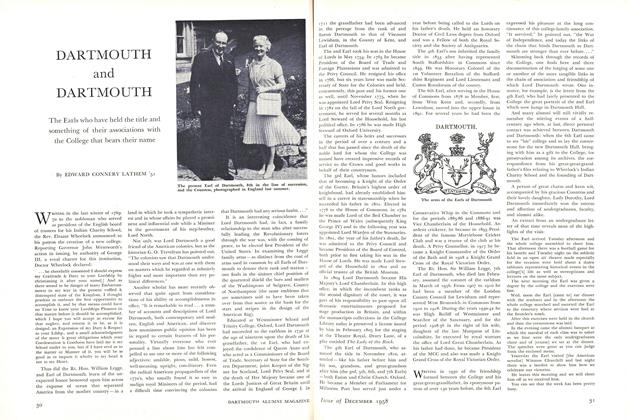

FeatureDARTMOUTH and DARTMOUTH

December 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

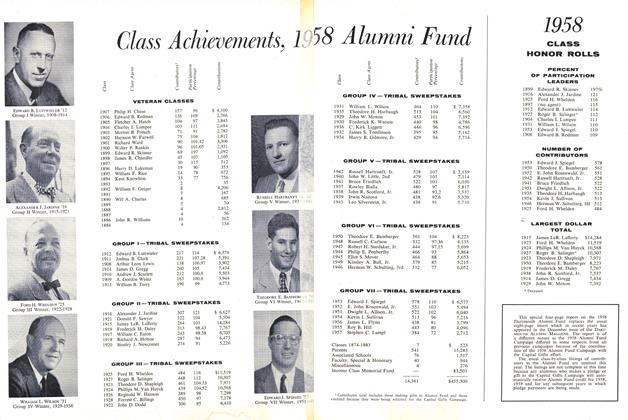

FeatureClass Achievements, 19

December 1958 -

Feature

FeatureLANGUAGE LABORATORY

December 1958 By PAUL R. OLSON, INSTRUCTOR -

Feature

Feature1958 ALUMNI FUND REPORT

December 1958 By William G. Morton '28, -

Feature

FeatureALUMNI FUND PLANS FOR 1959

December 1958 By Donald F. Sawyer '21,