By Carlos H. Baker'32. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 312pp. $3.95.

How refreshing it is to read a college novel by a teacher who likes his job! The prevailing mode of the academic fiction of our day has been satire, until no one could be blamed for concluding that the groves of academe bore only citrus fruit. In this formidable body of literature college administrators have usually been characterized as monsters of ineptitude or megalomania and professors as fogeys or phonies, psychopaths or subversives. That such distortions have delighted the Know-Nothings has not fazed the authors, so pure their spleen. If parents reading their works should conclude that any place from bootcamp to chain gang would offer a healthier environment for their sons than a college campus, even that would not deter these writers from their chosen task of cleansing the foul body of the infected academic world.

Carlos Baker, who as chairman of Princeton's English department should know whereof he speaks, feels differently. He is out to celebrate the dignity of his profession and the decency of his colleagues. He tells the story of an arduous but finally successful search for a new president of an Ivy League university. The task is undertaken by joint committees of trustees and faculty, meeting week after week under the mounting pressure of time. While they work, the exhausting and exhilarating business of education must go on; classes must be met, students come for conferences, other committees grind through their long agenda, and at home faculty children clamber precariously in tree houses and make Christmas lists. There are no villainous deans, sadistic registrars, or lycanthropic librarians. People behave well. They are neither silly nor sinister.

The result is, for another teacher, a book full of recognitions, not of individuals, for this is no roman a clef, but of types and patterns of experience. The story is true to the rhythm of academic life. It catches many of the commonest sensations of the calling — the half-hour of eager uncertainty before a lecture, the relaxed parenthesis of lunch time, the brief daydream while the secretary reads the minutes, the dead weight of 5:30 weariness. And never far from the center of Baker's concern is the persistent pride of the profession. It is good that the reading public should learn, from such a warm and lively novel, how we feel about our work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Examined Life

July 1958 By THE REV. THEODORE M. HESBURGH -

Feature

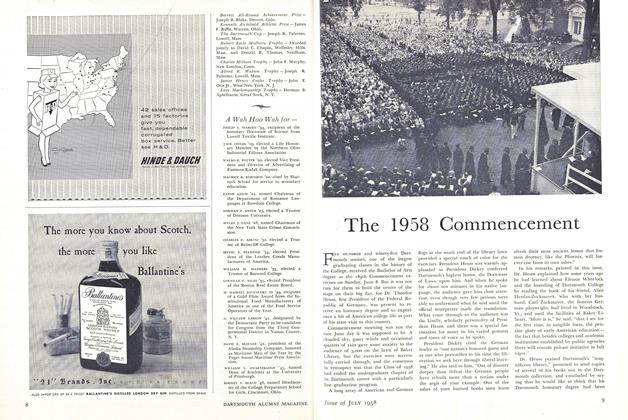

FeatureThe 1958 Commencement

July 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

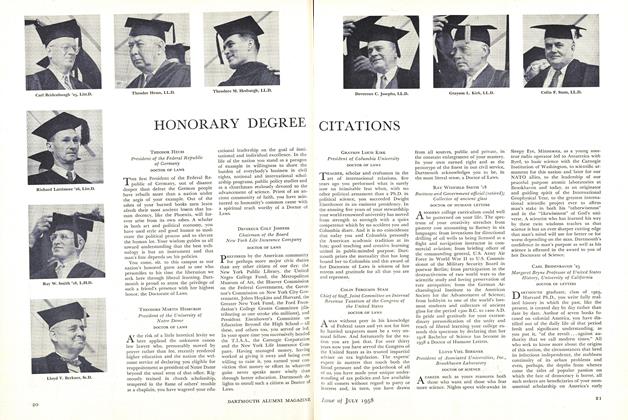

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1958 -

Feature

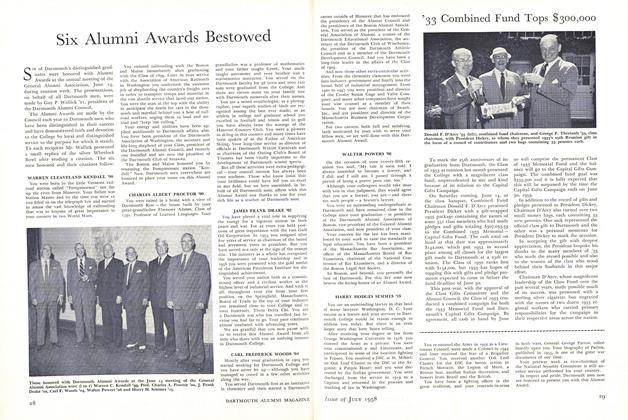

FeatureSix Alumni Awards Bestowed

July 1958 -

Feature

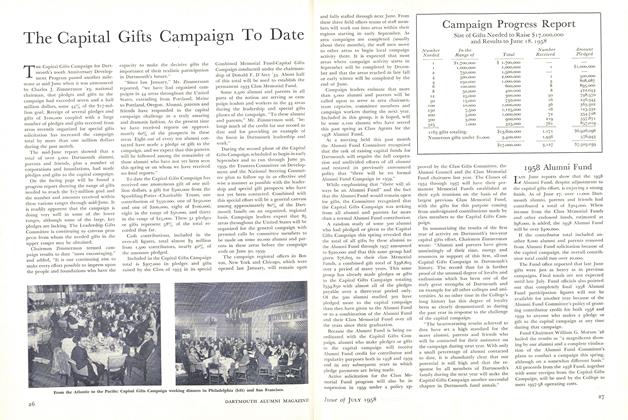

FeatureThe Capital Gifts Campaign To Date

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1958 By JAEGWON KIM '58

JOHN FINCH

-

Books

BooksSOME FACES IN THE CROWD.

June 1953 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksNOT FAR FROM THE JUNGLE.

January 1957 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksSCENERY FOR THE THEATRE: THE ORGANIZATION, PROCESSES, MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES USED TO SET THE STAGE.

MAY 1972 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksCREATIVE PLAY DIRECTION.

November 1974 By JOHN FINCH -

Article

ArticleThe Valedictories

JUNE 1977 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksTallulah to Travolta

November 1978 By JOHN FINCH

Books

-

Books

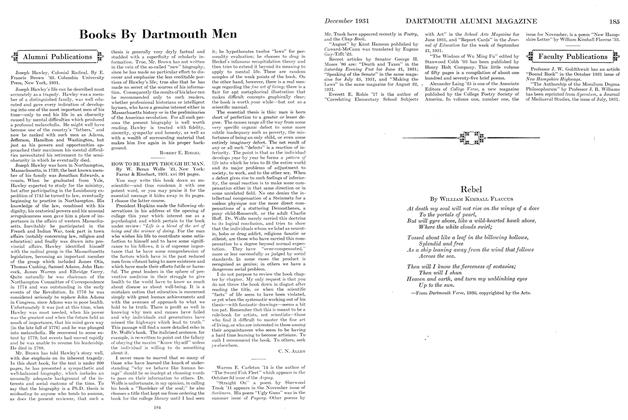

BooksProfessor J. W. Goldthwait has an article

DECEMBER 1931 -

Books

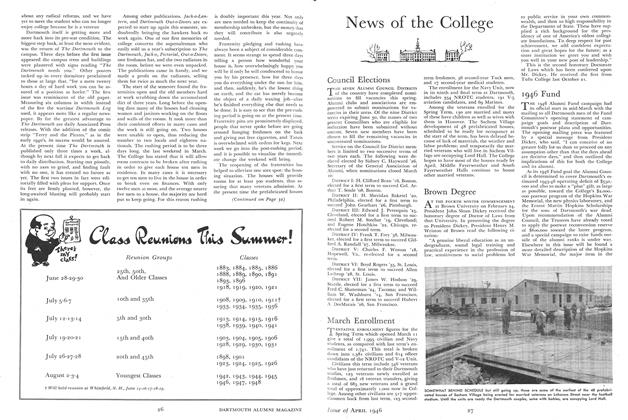

BooksFaculty Articles

April 1946 -

Books

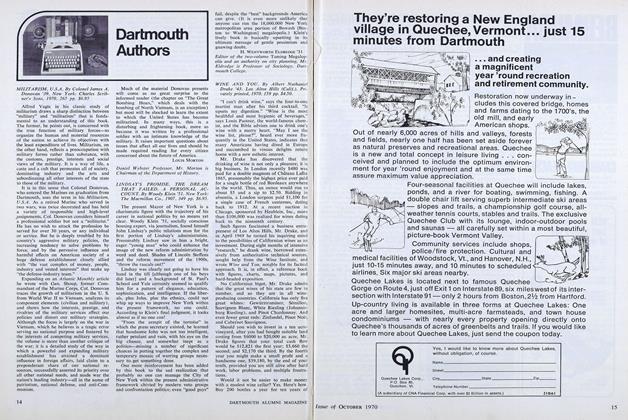

BooksWINE AND YOU.

OCTOBER 1970 By John Hurd ’21 -

Books

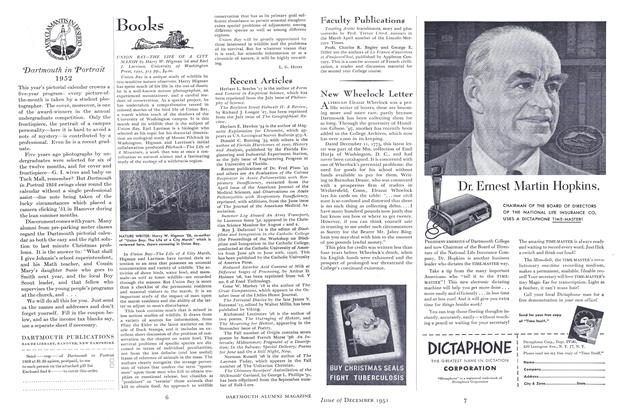

BooksUNION BAY-THE LIFE OF A CITY MARSH

December 1951 By L. G. Hines -

Books

BooksSTUDY-AND WIN

December 1946 By Louis P. Benezet '99. -

Books

BooksPRACTICAL FLIGHT TRAINING

November 1936 By Ramon Guthrie