LIKE you, I find I have memories which, in response to the season and the time, have been swimming up into consciousness these last few days. I remember my first mistake at Dartmouth, and my first triumph.

The mistake was missing an opportunity. When I arrived here, fresh from Harvard, in (God save the mark!) the fall of 1939, I was very young, and looked it. I looked so young, indeed, that, a couple of days before classes started, as I was walking past the then DKE House, two upperclassmen, mistaking me for a freshman, invited me to come in and carry their mattresses for them. But I wasn't a freshman; I was a lofty instructor! So I declined. That was the mistake, and I've regretted it ever since. Obviously, I should have accepted, and carried their damn mattresses, on the long but lovely chance that one or both of them might show up the following Monday in my first class.

The triumph was my initial encounter with omnipotence. In 1939 there was at Dartmouth a Faculty Club, located in Fairbanks Hall. There in the late afternoons certain raffish members of the faculty were wont to gather to play bridge. You know, an old tradition. One fall day, fancying myself as a bridge player, I wandered in all unannounced and almost instantly found myself in a game, sitting South to the formidable North of Dean E. Gordon Bill of the Department of Mathematics [and] dean of the faculty. Dean Bill was a prodigious presence, a rare combination of the immovable object and the irresistible force. The cards were dealt, he opened, and I trembled. I looked at my hand (my eyes had suddenly gone soft focus), counted the aces and kings, and then, step by vertiginous step, proceeded to bid him all the way up to a grand slam. With each of my bids, all of which were forcing, he muttered in his rumbling basso profundo, "This can't be right!" But miraculously, it was right. I put down my cards; he played them brilliantly, and made the slam. Then, without a word to me, he turned to our opponents and said, "Who is he? What's his name? Finch? What department? Promising chap!" You see, I had it made. Any later success I have enjoyed here at Dartmouth I ascribe entirely to that bridge hand.

But whatever our memories of mistakes or triumphs, now it's graduation, or better, commencement. I've always preferred that word. Graduation somehow suggests grades, of which we are all sick. Commencement has a finer ring. Something, for all of us, is commencing.

What is it that is commencing for you? Some of you would answer, I suppose, "The real world." I confess I don't understand the distinction implied in that phrase. Does it mean that, after the unreality of Dartmouth, you go to encounter the reality of some place else? But why is a pine tree any less real than a subway turnstile? Or a snowstorm less real than a traffic jam? Or the Connecticut River less real than the Atlantic Ocean? Besides, Plato has a warning for us about ascribing ultimate reality to anything in this world of appearances - flickering, insubstantial shadows on the walls of our cave. No, I don't believe it is the real world that is commencing for you this weekend. But I do believe it is your real education.

What will be the content of this new education you are about to commence? Well, it will be the ultimate curriculum, the great issues, you must study. Once we undertook to construct here at Dartmouth a required course for seniors. We named it the Great Issues Course, and then got down to trying to define it and give it content. What should we include? History, science, literature, politics, economics? We sought out help from wise and learned people, and it was one of our consultants, the poet Archibald MacLeish, who gave us, I think, the best advice. "There are only three great issues," he said, "the relationship between a man and a woman, the relationship between a parent and a child, and the relationship of an individual to death." Perhaps that indicates something about the curriculum of the education ahead of you.

But how do you address yourselves to that ultimate curriculum, those great issues? It is a popular formulation for commencement speakers at liberal arts colleges to say that in your undergraduate years you have indulged in generalizing, now you specialize. It is a persuasive formulation, for graduate schools, to which many of you are headed, are specialize places; and professions or vocations do require specialized skills and sharply focused knowledge. But the trouble with that formulation is that it sidesteps those very great issues, which require you to move in breadth as well as depth. Life makes, whether we like it or not, generalists of us all. Faced with its demands, we are all amateurs, even dilettantes.

How do you pursue that ultimate curriculum? Of necessity, I think, in two ways, for education itself is two-pronged, and always poses a double requirement. You must measure, and you must evaluate. In this so quantified world, where often the future itself seems to depend on the absolute accuracy of a single measurement, we aren't allowed the luxury of approximation. For measurement, Dartmouth has given you some of the tools.

But it isn't enough to measure, to quantify, or to compute, for value judgments must finally be made, and, like beggars, computers can't be choosers. You will someday soon have to answer, not only the question, "What is true?", but also the greater question, "What is good?" Then, if you put your faith in computation, it will betray you. Unaided by measurement, you will have to make a choice. For that choice, I hope, Dartmouth has also given you some of the tools.

To clarify what I am trying to say, let me turn to another poet. Robert Frost once showed me a line in Shakespeare I had never seen before, although I had read it a hundred times. It's in one of the sonnets, the 116th.

It is the star to every wandering bark,Whose worth's unknown, although hisheight be taken.

"There it is," Frost said, "don't you see? The two kinds of education - measuring the height of the star, and knowing its worth."

As a humanist, and one who wishes you well, I can only urge you, in the great education ahead of you, try to do both.

It is the star to every wandering bark,Whose worth's unknown, although hisheight be taken.

In case you don't remember the rest of the sonnet, the antecedent of the pronoun, it - the star - is love.

FOUR years ago, as I was about to enter Dartmouth as a freshman, an alumnus of the College spoke to me about the unique qualities of education at Dartmouth. He said that the most valuable knowledge I would gain here would not be derived solely from academics, because a fine education could be obtained at a number of other institutions - what was unique about Dartmouth, he felt, was the type of people I would meet. It would be the interaction with my peers that would be the true learning experience at the College, and I would gain more from those about me than I could from any book. I realize now, more than ever, that he was indeed correct. People make Dartmouth special, and have since the 1950s when he was a senior. I hope that in the generations to come this will still be the case.

To insure that Dartmouth will remain that special place, the College must continue to meet the ever-changing needs of future classes. Isolated from the mainstream of society, we at Dartmouth tend to be a bit reactionary, citing yesterday's traditions and clinging to the ideal of the "good old days." We sometimes lose sight of the fact that the old Dartmouth could no more serve us than the College of today could serve our children's generation. We, as alumni, now have the responsibility to see that the College continues to develop and progress along with society. We cannot expect a static Dartmouth to prepare her students to enter a dynamic world. We must not allow the College to become cloistered here in the hills of New Hampshire, for our primary commitment is to prepare students for their roles in a progressive society. As alumni, we must encourage Dartmouth to keep growing and developing new potentials. The one tradition we must cling to is the exceptional type of education offered by Dartmouth.

In a very real sense, Dartmouth is no longer ours - it belongs to the classes of the future. I hope that in 20 years the College will still be reflecting a commitment to progressive education, and that I will be proud to have my children apply here. I also hope that I can tell my children about the "good old days" of 1977 - knowing that the changes the College has undergone since this day have made Dartmouth better able to prepare them for their future. The College has given us four very special years. Let us respond in kind, and work to insure that Dartmouth is able to give future generations the same.

MARK REID DESNOYERS '77

AT the opening of College when you entered as freshmen, I said as part of my speech: "We are here to celebrate the annual renewal in the life of the College. No event is happier than the celebration of the birth of a child, and the bigger the baby the happier the celebration. Dartmouth today has given birth to a new freshman class and it is the biggest class ever. As proud and prejudiced parents we believe the infant is the brightest and most talented child ever born. ..." [Today] is a traumatic experience. The child has grown up. We ask ourselves have we given all the loving care that we should have, or would one more spanking have improved the product?

What last words of advice would be helpful today? I asked myself what if I had a daughter or a son in the graduating class, what words would I want her or him to hear? I would like to say that in a class this large many of you will achieve fame or fortune. We will be very proud of you when you do. But fame and fortune are not the most important things in life, nor will fame and fortune alone assure you of contentment. The most important thing is to achieve an inner peace in a knowledge that your life is worthwhile. There is no single route to achieve that inner peace - you are each a unique human being and what may be best for the father may be wrong for the son - but there are some guiding principles. . . .

Give of yourself freely. Give to friendship, give to family, give to your community, and give to your country. There is a great satisfaction in belonging to a group, but don't automatically follow the herd. There will be moments, often lonely ones, when you alone can decide what is right for you. At Dartmouth we have tried to give you a good education (whether you took advantage of it or not), but we have tried to give you more. We hope you have formed friendships that will last a lifetime. We hope that you have learned to care about the college that cares greatly about you. Thousands of alumni 'round the girdled earth have had their lives enriched by a continuing relation with Dartmouth. Of course, to an undergraduate an alumnus is a strange, mythical creature. We've heard you speak of them in wonder - and in anger - when you speculated about what the alumni are thinking. And you said just who are they? Well, you can stop wondering. Now you are they.

In that same convocation address to your class I said that institutions that survive centuries do so by always changing and yet always remaining true to their basic purpose. As alumni of Dartmouth, help us change for the better and at the same time fight to preserve the best of the traditions of the College. Above all, do not ever become indifferent - indifferent to the fate of your friends, of your family, or of your college or your fellow human beings. For, men and women of Dartmouth, all mankind is your brother and you are your brother's keeper.

JOHN G. KEMENY

This year's efforts, commendably to thepoint, were both admonishing and encouraging in tone. Among the principalspeakers were John Finch, retiring KenanProfessor of Drama, who bid farewell tothe seniors on Class Day; Mark Desnoyers'77, a pre-med student with academiccitations in fully a third of his undergraduate courses (ranging fromphilosophy to chemistry, from history tophysics), who delivered the senior valedictory; and President Kemeny, who did, indeed, have a son (Robert) among thegraduates.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMerchant of Menace, Purveyor of Pleasure

June 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureYesterday's Glories Tomorrow's ?

June 1977 By JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

FeatureThey Also Went Forth

June 1977 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1977 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1977 -

Article

ArticleMr. Badger Makes the Boats Go

June 1977 By B.W.B.

JOHN FINCH

-

Books

BooksSOME FACES IN THE CROWD.

June 1953 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksNOT FAR FROM THE JUNGLE.

January 1957 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksA FRIEND IN POWER.

July 1958 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksSHAKESPEARE AND THE COMEDY OF FORGIVENESS.

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksCREATIVE PLAY DIRECTION.

November 1974 By JOHN FINCH -

Books

BooksTallulah to Travolta

November 1978 By JOHN FINCH

Article

-

Article

ArticleHOLIDAY MAKES ALL THINGS RIGHT

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

December 1953 -

Article

ArticleWhat Ever Happened to Skijoring?

FEBRUARY 1989 -

Article

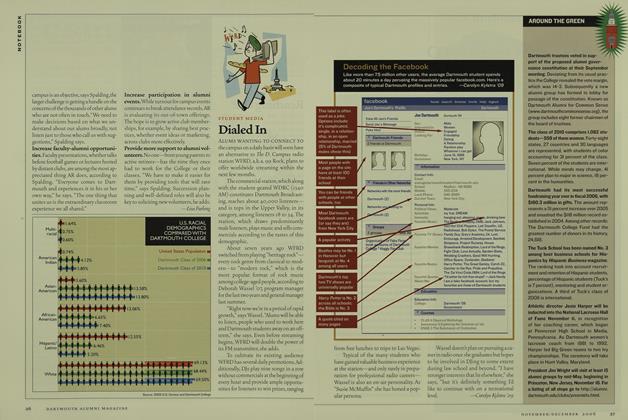

ArticleDialed In

Nov/Dec 2006 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticleRemember Those Days?

June 1933 By H. P. Hinman '10 -

Article

ArticleRockefeller Gift of $250,000

November 1950 By John D. Rockefeller Jr.