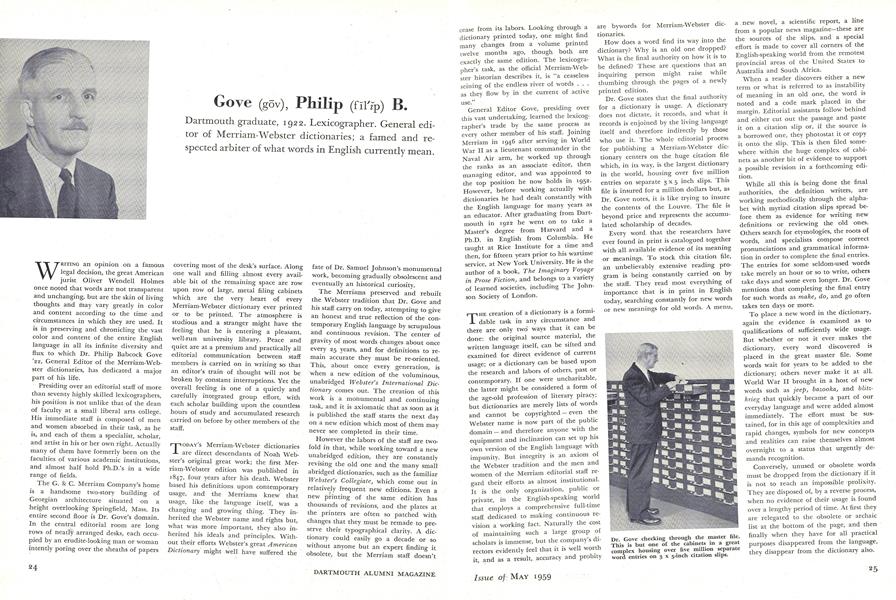

Dartmouth graduate, 1922. Lexicographer. General editor of Merriam-Webster dictionaries; a famed and respected arbiter of what words in English currently mean.

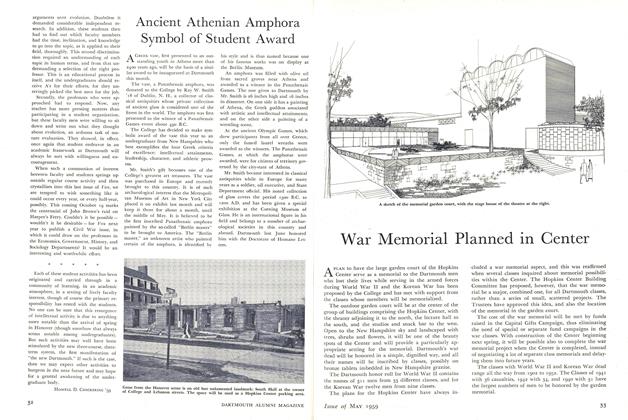

WRITING an opinion on a famous legal decision, the great American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes once noted that words are not transparent and unchanging, but are the skin of living thoughts and may vary greatly in color and content according to the time and circumstances in which they are used. It is in preserving and chronicling the vast color and content of the entire English language in all its infinite diversity and flux to which Dr. Philip Babcock Gove '22, General Editor of the Merriam-Webster dictionaries, has dedicated a major part of his life.

Presiding over an editorial staff of more than seventy highly skilled lexicographers, his position is not unlike that of the dean of faculty at a small liberal arts college. His immediate staff is composed of men and women absorbed in their task, as he is, and each of them a specialist, scholar, and artist in his or her own right. Actually many of them have formerly been on the faculties of various academic institutions, and almost half hold Ph.D.'s in a wide range of fields.

The G. & C. Merriam Company's home is a handsome two-story building of Georgian architecture situated on a height overlooking Springfield, Mass. Its entire second floor is Dr. Gove's domain. In the central editorial room are long rows of neatly arranged desks, each occupied by an erudite-looking man or woman intently poring over the sheaths of papers covering most of the desk's surface. Along one wall and filling almost every available bit of the remaining space are row upon row of large, metal filing cabinets which are the very heart of every Merriam-Webster dictionary ever printed or to be printed. The atmosphere is studious and a stranger might have the feeling that he is entering a pleasant, well-run university library. Peace and quiet are at a premium and practically all editorial communication between staff members is carried on in writing so that an editor's train of thought will not be broken by constant interruptions. Yet the overall feeling is one of a quietly and carefully integrated group effort, with each scholar building upon the countless hours of study and accumulated research carried on before by other members of the staff.

TODAY'S Merriam-Webster dictionaries are direct descendants of Noah Webster's original great work; the first Merriam-Webster edition was published in 1847, four years after his death. Webster based his definitions upon contemporary usage, and the Merriams knew that usage, like the language itself, was a changing and growing thing. They inherited the Webster name and rights but, what was more important, they also inherited his ideals and principles. Without their efforts Webster's great AmericanDictionary' might well have suffered the fate of Dr. Samuel Johnson's monumental work, becoming gradually obsolescent and eventually an historical curiosity.

The Merriams preserved and rebuilt the Webster tradition that Dr. Gove and his staff carry on today, attempting to give an honest and true reflection of the contemporary English language by scrupulous and continuous revision. The center of gravity of most words changes about once every 25 years, and for definitions to remain accurate they must be re-oriented. This, about once every generation, is when a new edition of the voluminous, unabridged Webster's International Dictionary comes out. The creation of this work is a monumental and continuing task, and it is axiomatic that as soon as it is published the staff starts the next day on a new edition which most of them may never see completed in their time.

However the labors of the staff are twofold in that, while working toward a new unabridged edition, they are constantly revising the old one and the many small abridged dictionaries, such as the familiar Webster's Collegiate, which come out in relatively frequent new editions. Even a new printing of the same edition has thousands of revisions, and the plates at the printers are often so patched with changes that they must be remade to preserve their typographical clarity. A dictionary could easily go a decade or so without anyone but an expert finding it obsolete, but the Merriam staff doesn't cease from its labors. Looking through a dictionary printed today, one might find many changes from a volume printed twelve months ago, though both are exactly the same edition. The lexicographer's task, as the official Merriam-Webster historian describes it, is a ceaseless seining of the endless river of words . . . as they flow by in the current of active use."

General Editor Gove, presiding over this vast undertaking, learned the lexicographer's trade by the same process as every other member of his staff. Joining Merriam in 1946 after serving in World War II as a lieutenant commander in the Naval Air arm, he worked up through the ranks as an associate editor, then managing editor, and was appointed to the top position he now holds in 1952. However, before working actually with dictionaries he had dealt constantly with the English language for many years as an educator. After graduating from Dartmouth in 1922 he went on to take a Master's degree from Harvard and a Ph.D. in English from Columbia. He taught at Rice Institute for a time and then, for fifteen years prior to his wartime service, at New York University. He is the author of a book, The Imaginary Voyagein Prose Fiction, and belongs to a variety of learned societies, including The Johnson Society of London.

THE creation of a dictionary is a formidable task in any circumstance and there are only two ways that it can be done: the original source material, the written language itself, can be sifted and examined for direct evidence of current usage; or a dictionary can be based upon the research and labors of others, past or contemporary. If one were uncharitable, the latter might be considered a form of the age-old profession of literary piracy; but dictionaries are merely lists of words and cannot be copyrighted - even the Webster name is now part of the public domain - and therefore anyone with the equipment and inclination can set up his own version of the English language with impunity. But integrity is an axiom of the Webster tradition and the men and women of the Merriam editorial staff regard their efforts as almost institutional. It is the only organization, public or private, in the English-speaking world that employs a comprehensive full-time staff dedicated to making continuous revision a working fact. Naturally the cost of maintaining such a large group of scholars is immense, but the company's directors evidently feel that it is well worth it, and as a result, accuracy and probity are bywords for Merriam-Webster dictionaries.

How does a word find its way into the dictionary? Why is an old one dropped? What is the final authority on how it is to be defined? These are questions that an inquiring person might raise while thumbing through the pages of a newly printed edition.

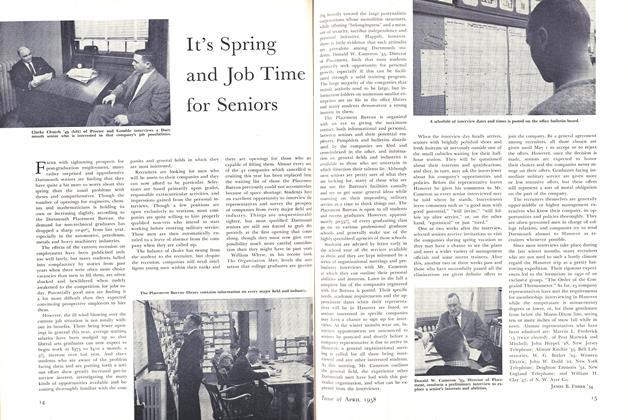

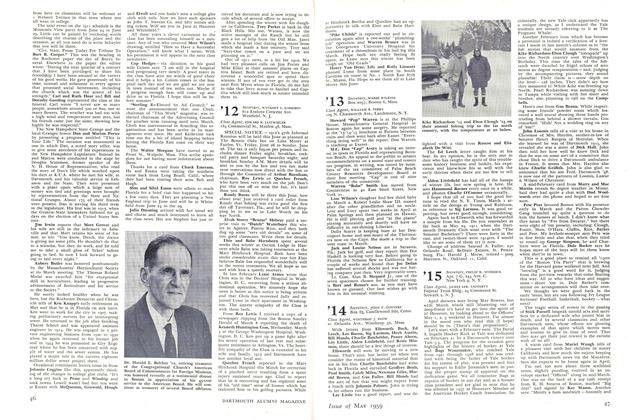

Dr. Gove states that the final authority for a dictionary is usage. A dictionary does not dictate, it records, and what it records is enjoined by the living language itself and therefore indirectly by those who use it. The whole editorial process for publishing a Merriam-Webster dictionary centers on the huge citation file which, in its way, is the largest dictionary in the world, housing over five million entries on separate 3x5 inch slips. This file is insured for a million dollars but, as Dr. Gove notes, it is like trying to insure the contents of the Louvre. The file is beyond price and represents the accumulated scholarship of decades.

Every word that the researchers have ever found in print is catalogued together with all available evidence of its meaning or meanings. To stock this citation file, an unbelievably extensive reading program is being constantly carried on by the staff. They read most everything of importance that is in print in English today, searching constantly for new words or new meanings for old words. A menu, a. new novel, a scientific report, a line from a popular news magazine—these are the sources of the slips, and a special effort is made to cover all corners of the English-speaking world from the remotest provincial areas of the United States to Australia and South Africa.

When a reader discovers either a new term or what is referred to as instability of meaning in an old one, the word is noted and a code mark placed in the margin. Editorial assistants follow behind and either cut out the passage and paste it on a citation slip or, if the source is a borrowed one, they photostat it or copy it onto the slip. This is then filed somewhere within the huge complex of cabinets as another bit of evidence to support a possible revision in a forthcoming edition.

While all this is being done the final authorities, the definition writers, are working methodically through the alphabet with myriad citation slips spread before them as evidence for writing new definitions or reviewing the old ones. Others search for etymologies, the roots of words, and specialists compose correct pronunciations and grammatical information in order to complete the final entries. The entries for some seldom-used words take merely an hour or so to write, others take days and some even longer. Dr. Gove mentions that completing the final entry for such words as make, do, and go often takes ten days or more.

To place a new word in the dictionary, again the evidence is examined as to qualifications of sufficiently wide usage. But whether or not it ever makes the dictionary, every word discovered is placed in the great master file. Some words wait for years to be added to the dictionary; others never make it at all. World War II brought in a host of new words such as jeep, bazooka, and blitzkrieg that quickly became a part of our everyday language and were added almost immediately. The effort must be sustained, for in this age of complexities and rapid changes, symbols for new concepts and realities can raise themselves almost overnight to a status that urgently demands recognition.

Conversely, unused or obsolete words must be dropped from the dictionary if it is not to reach an impossible prolixity. They are disposed of, by a reverse process, when no evidence of their usage is found over a lengthy period of time. At first they are relegated to the obsolete or archaic list at the bottom of the page, and then finally when they have for all practical purposes disappeared from the language, they disappear from the dictionary also. GOVE finds that his work has become a perpetual part of his life and he spends many a night at home reviewing entries and definitions. He, or one of two associate editors, passes final judgment on every new entry that leaves the Merriam-Webster editorial offices for the Riverside Press in Cambridge, Mass., where the actual printing is done. It is up to him to see that his writers concentrate solely upon the evidence before them, and the style of dictionaries must be concise, comprehensive and, above all, accurate. The proof-reading must be meticulous; a misspelling would be embarrassing, to say the least.

Recording the language, possibly more than any other task of modern scholarship, is a communal venture, and every member of the editorial staff has had some small or large part in each new edition. But the work is exacting and in a way lonely, demanding a suitable temperament and a certain amount of dedication. Many leave the Merriam editorial offices after four or five years to return to the pleasant and sequestered avenues of their college or university campuses. Dr. Gove must direct a permanent training program to compensate for this turnover since it takes at least six months to train a new editorial worker in a course that is considerably more demanding than that of any graduate school in any field. Practically every new staff member must go through this program since no advanced work in lexicography is given anywhere.

For those such as Dr. Gove who do find their temperament suited for the work, it can be fascinating and exciting. Two or three thousand letters a year come in requesting information about words and their usages. These are all answered personally by one of the editorial staff and many of them by the General Editor himself. The staff feels a responsibility for answering these inquiries, since the world over they are regarded as objective arbiters of the English language. Dr. Gove states emphatically that there can never be a really final or definitive authority for the language since it is the people writing and speaking it who make the final judgment, but the descendants of Webster humbly attempt to answer the questions as accurately as possible on the basis of the massive evidence they have stored within their reach. To them there can be no ultimate or perfect dictionary, but they attempt to come as close to it as possible.

Many of the letters are from cranks, some wondering why a certain word is not in the dictionary and others wondering why one is. Dr. Gove cites one letter complaining that the inclusion of the word gremlin in the Merriam-Webster dictionaries implied a recognition of the word as a reality. But he answers that the dictionary recognizes only the way people use the symbols representing realities or concepts, not the realities or concepts themselves. He feels that this is one of the major reasons for our taboos and prejudices, that people often do not recognize words for the abstractions they really are."

After leaving his daytime scholarship with his dictionaries, the learned doctor becomes just plain Phil Gove to his friends and fellow alumni. He fancies himself a part-time farmer of sorts and commutes 25 miles every day to his 210-acre farm in Warren, Mass., where he and his wife Grace finish up any odd chores. He prides himself on having had the foresight, when he first joined Merriam, to find a place to live so located that he wouldn't have to drive into the sun twice a day.

Dr. Samuel Johnson, possibly the greatest lexicographer of the English language, referred to himself as "a compiler of dictionaries; a harmless drudge." But to Dr. Philip Gove the task is not drudgery; in its way it is a journey, with new worlds opening up every day - the infinite worlds of words, symbols that are the very reflection of life itself. It is an exacting task and must often be a painful one, but certainly not drudgery to such a man with the mind of a scholar and the spirit of an adventurer.

Dr. Gove checking through the master file. This is but one of the cabinets in a great complex housing over five million separate word entries on 3 x 5-inch citation slips.

A page from a best-seller marked for citation. A typist will transfer the marked passages onto slips to be filed away as potential evidence for the definition writers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

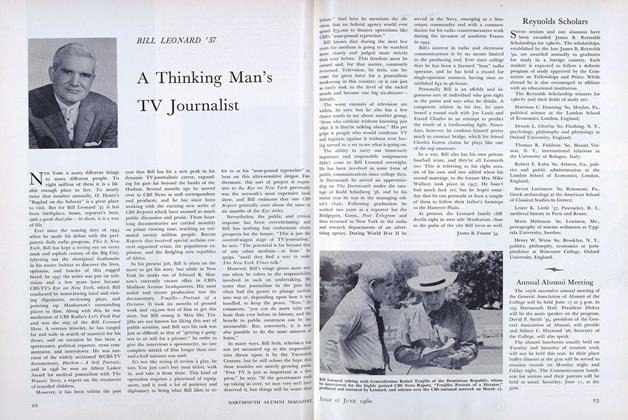

FeatureDartmouth Study Urges ROTC Program Changes to Meet Nation's Needs

May 1959 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureFourteen Gained — Three to Go

May 1959 -

Feature

FeatureWar Memorial Planned in Center

May 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

May 1959 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

May 1959 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, JAMES LeR. LAFFERTY -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59

JAMES B. FISHER '54

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryQuite Good

MARCH 1995 By Abner Oakes IV '81 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Plan

JANUARY 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

Feature"The Working of the Religious Element"

October 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Feature

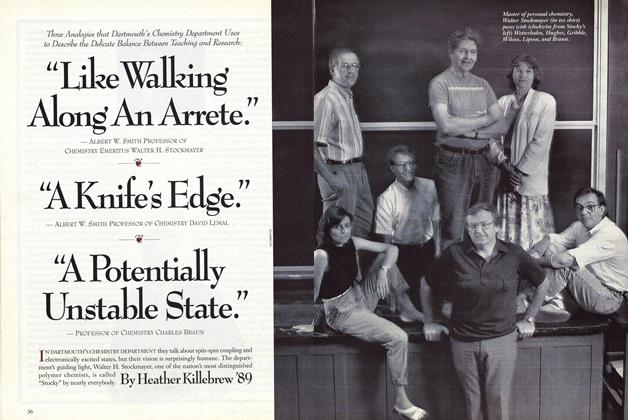

Feature"Like Walking Along an Arrete."

OCTOBER 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

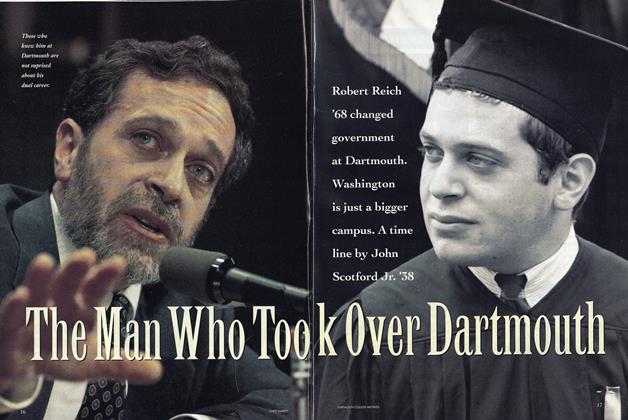

FeatureThe Man Who Took Over Dartmouth

May 1993 By John Scotford Jr. '38 -

Feature

FeatureStudents in a "Goldfish Bowl" Rise to Debate

MAY 1989 By Ron Lepinskas '89