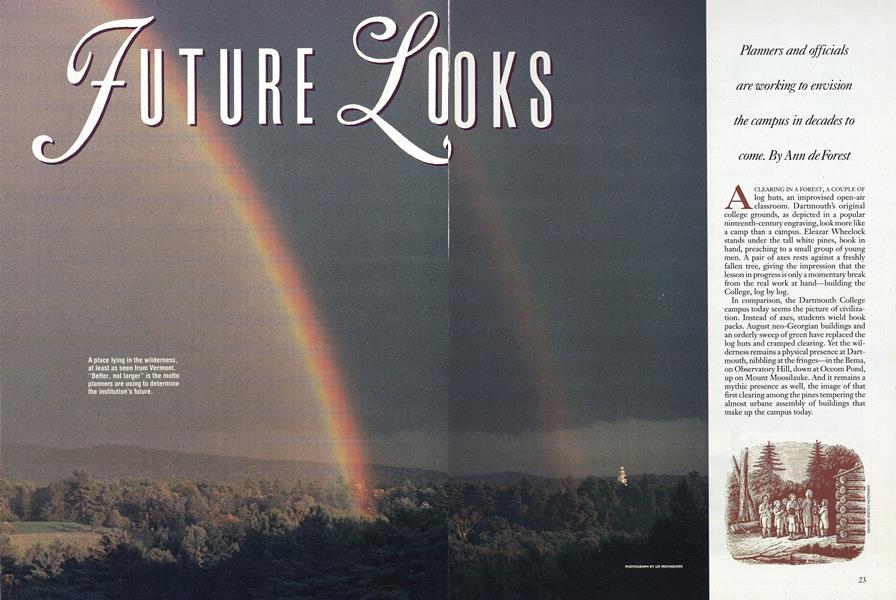

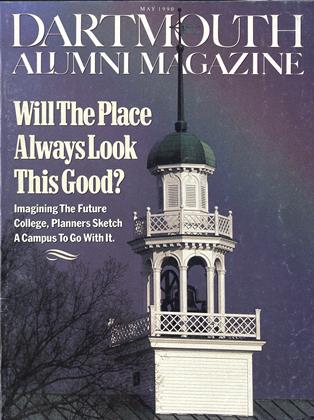

Planners and officialsare working to envisionthe campus in decades tocome.

A CLEARING IN A FOREST, A COUPLE OF log huts, an improvised open-air classroom. Dartmouth's original college grounds, as depicted in a popular ninteenth-century engraving, look more like a camp than a campus. Eleazar Wheelock stands under the tall white pines, book in hand, preaching to a small group of young men. A pair of axes rests against a freshly fallen tree, giving the impression that the lesson in progress is only a momentary break from the real work at hand—building the College, log by log.

In comparison, the Dartmouth College campus today seems the picture of civilization. Instead of axes, students wield book packs. August neo-Georgian buildings and an orderly sweep of green have replaced the log huts and cramped clearing. Yet the wilderness remains a physical presence at Dartmouth, nibbling at the fringes—in the Bema, on Observatory Hill, down at Occom Pond, up on Mount Moosilauke. And it remains a mythic presence as well, the image of that first clearing among the pines tempering the almost urbane assembly of buildings that make up the campus today.

A COLLEGE CAN, IN THEORY, EXist without a campus. All that's needed is a faculty, some willing students, and a place for the two groups to gather. The nature of the place doesn't matter. It could be a church basement, a sidewalk cafe, a local bar—or, following Eleazar Wheelock's model, a couple of log huts under the pines.

But, in the American imagination, college and campus are so closely intertwined that separating one from another is impossible. A college's architecture, layout, and landscape provide the school with an identity, with character. Students and faculty may give a school its reputation, but, as mere mortals, they tend to be transient. A campus endures.

So, Yale, with its richly cadenced sequences of spires, towers, and enclosed quadrangles, seems complex and secretive. The Gothic cloisters of Bryn Mawr College convey a romantic air of solitude and contemplation. And Dartmouth's campus, with its open, austere Green and stylistically unified buildings, expresses satisfied self-confidence.

Still, what a campus represents to one generation can be very different from what it represents to another. For alumni, the physical presence of the alma mater, the campus and its buildings, serves as a kind of totem, an evocative reminder of tribal bonds and rituals. The present generation of students, on the other hand, appreciates the campus for its functional amenities as well as its symbolic value. These students endow certain spaces and nooks with meaning, some traditional—conforming to the collective significance bestowed on a place—some personal—an outdoors retreat, a favorite window seat in the library—but it is a significance devoid of nostalgia, rooted in the here and now. Then there's the phantom future generation of students, with their as yet undefined needs and expectations which, nevertheless, must be addressed.

A college campus somehow has to accommodate all three—past, present, and future. This makes colleges paradoxical places by nature, at once conservative and progressive, rooted in tradition but committed to the next generation. How does a college campus cope with paradox? How can it meet the needs of the future without damaging the core of its identity, without changing its fundamental character?

That is the dilemma Dartmouth College faces right now. It's a dilemma that lies in an opportunity: the College's acquisition of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center properties. The center, which includes the Medical School, hospital, and clinic, is moving more than two miles down the road to a $218 million complex in Lebanon, New Hampshire. The College has already bought the old hospital buildings, which are scheduled to become vacant in late 1991. The extra land and floor space—a total of 560,000 square feet—offer all sorts of tempting options. Over the decades to come, Dartmouth could expand existing programs or add new ones, move academic departments out of cramped quarters, even eventually increase the size of the student body. Physically, the visually chaotic north end of campus can finally have form and identity. As College Facilities Planner Gordon DeWitt '60 remarks, "Dartmouth has an opportunity to put a north face on our campus that never existed before."

The situation, for Dartmouth, has been a little like winning the lottery. Dreaming about radical changes in lifestyle is fan for a while. But heady fantasies eventually give way to anxiety. For the Dartmouth administration, the anxiety was that the additional property would force the school to change more than it should, or wanted to. Denise Scott Brown, the planning consultant whom the College engaged to develop a long-range concept plan for the area, explains: "There's a lot of fear. They're afraid these buildings might drive them to become Dartmouth Institute of Technology. And that's not what they have in mind as the mission of the College."

As any lottery winner knows, to alleviate anxiety and make the most of one's windfall takes realistic, carefully considered, longrange planning. That's why Dartmouth turned to Denise Scott Brown. Principal in the Philadelphia architectural firm Venturi Scott Brown and Associates, Scott Brown and her husband, Robert Venturi, are best known, at least to the general public, as architects and theorists. Their seminal book Learning

from Las Vegas (1972) championed "ugly and ordinary" vernacular architecture, rich in symbol and meaning, over the blank and pretentious monuments of modernism. As designers and planners, the Venturis pay affectionate and knowing homage to the and traditions of a place, whether that place be a downtown business district, Trafalgar Square, or a college campus.

"What's so good about...the Venturis is they have a great sensitivity to context," observes George Hathorn, Dartmouth College Architect. For Dartmouth, such sensitivity is key. "A lot of what makes Dartmouth great in terms of a campus environment is already here. New buildings should be background."

Not that the firm's buildings look entirely anonymous. The ornamental richness and distilled allusions found in buildings like Wu Hall at Princeton or the recently completed annex to Dartmouth's Thayer School of Engineering wryly comment on and direct attention to the architectural traditions of the past. The Thayer addition is an example. While adding to Dartmouth's comprehensive catalog of neo-Georgian architecture, the new design also enlivens the whole parade of neo-Georgian buildings along Tuck Mall.

Style is only one of several contextual issues Denise Scott Brown has to consider in developing a concept plan for Dartmouth. Foremost is the issue of mission, defining the strategic goals of the institution. Usually, campus planning follows academic changes. When, for example, Princeton recently decided to change from a dormitory to a college system after the model of Harvard and Yale, Venturi Scott Brown plotted and directed the physical aspects of the metamorphosis. Dartmouth has withstood dramatic alterations to its campus in the past, and these changes also reflected a considered shift in policy, in goals and objectives. Around the turn of the century, President William Jewett Tucker, dedicated to bringing Dartmouth out of its benighted provincialism, fulfilled his goals by giving the College new physical form. Under Tucker, the college on the hill, a simple row of buildings on the east side of the Hanover town green, ambitiously expanded its scope—academically and physically. Bold new subjects, such as modern language instruction, were added to the curriculum. And the College surrounded the Green. Under Tucker's leadership, the poor backwater institution quickly became a school of national stature.

Changes today occur on a considerably smaller scale. Still, academic need continues to guide campus design decisions at Dartmouth. "We've never built a building that didn't address how it's going to serve the mission of the College," Gordon DeWitt maintains. "An institution doesn't have the luxury of putting up a monument that doesn't fulfill a program."

But the acquisition of the Medical Center properties upset the natural order of things. Physical considerations suddenly threatened to dictate policy moves. Assessing the situation, Scott Brown and her team of planners and designers had to help maintain the proper balance. She suggested that the academic Planning Steering Committee be the body to advise the Concept Plan, paralleled by the process of soul-searching taking place in the Provost's office, on the Design Review Committee, and in the Facilities Planning Office. She asked the committees to assess each option for the hospital property by considering the question: "What do we really, really want to be?" She believed that only through such a painstaking analysis could they adequately consider: "how do we ingest... this great windfall in a creative way?"

The planning process has several phases. Currently the planners and the committee are concentrating on immediate, short-term issues, proposals for the expansion of Baker Library and what Scott Brown calls "the nitty-gritty of hospital re-use." But before asking the committees to focus on such specific questions as whether to demolish, mothball, or "paint and powder" individual buildings, Scott Brown presented several long-term concepts, visions of what the old Medical Center site might look like 50 years from now. Once the committees decide on a long-range vision, it will become the lodestar for the campus, setting the course for more immediate choices. "You don't make short-term decisions without a long-range plan," explains Provost John Strohbehn. "You don't go placing a building in a spot you might want to use for something else later." (Dartmouth's administrators are careful to note that, while the plan allows for sigificant growth, they do not actually anticipate it—at least for the next ten or 15 years.)

The block of campus between Elm and Maynard Streets currently stands as a testament to such short-sighted decision making. (Although, as Scott Brown warns those quick to condemn the past, "It's difficult to know what's a shortsighted decision without hindsight.") Facing the back of Baker Library, the traditional northern boundary of the campus, the Elm-Maynard block has long looked like an afterthought—a hodgepodge of poorly sited buildings with haphazardly carved parking lots filling in the leftover spaces. The Medical Center windfall lets Dartmouth reshape this stretch of campus. Peter Robbie '69, chairman of the Design Review Committee, sees a "once in a lifetime opportunity to make a solution for the area that isn't a compromise."

Indeed, a reformed Elm-Maynard stands as the centerpiece of Scott Brown's 50-year proposal. As the essential link between the traditional campus and the newly annexed hospital properties, the area becomes an integral part of the Dartmouth campus as a whole. The remodeled block can also resolve some practical problems for the Dartmouth campus. The topography of the site makes it suitable for an underground parking garage, an amenity the car-strangled campus desperately needs. Scott Brown, in consultation with transportation engineers Robert B. Morris Associates, has also suggested a scenario that would close Elm Street to traffic. No longer artery or barrier, the re-landscaped road would help tie the two parts of campus together.

Scott Brown proposed several alternatives for the site. One, the whimsically named and conceived "Duck Pond," flooded the area, creating a picturesque but otherwise useless bird sanctuary in the center of campus. A radically impractical design, the Duck Pond, says Scott Brown, had a very practical purpose. "We use these caricatures as heuristics," she explains. "The purpose of the Duck Pond was to define the extremes so I could find the range of what was feasible." Al-though a few committee members defended the proposal, the majority quickly rejected the Duck Pond as "extravagant," according to Robbie.

The "Romantic Landscape" emphasizes the rolling topography of the site. Nestled among the trees, an arc of buildings rings around a horseshoe curve of grass. The layout and landscape recall the bits of wilderness scattered along the edge of the campus. But, brought into the heart of campus, the wilderness turns domestic, loses some of its mythic mystery and power.

The Design Review Committee's favored scheme, so far, is Scott Brown's "Quad" proposal. The Quad echoes the neat, precise geometry of the rest of the Dartmouth campus. Rows of rectangular buildings, inspired by New England mill architecture, flank a strong, linear axis that runs through the center of the block, forging a convincing link between the library and the Medical Center buildings. Hathorn finds the Quad scheme "excellent. It provides a range of visual amenities and enriches the campus in a way that adding another Green on the north side wouldn't."

Does the Quad scheme adequately embody Dartmouth's abstract goals and principles? Does it express how the present administration envisions Dartmouth 50 years from now? By not being a second Green, a grandiose new campus, the proposal does what the committees have asked it to do. For while the Quad expands the purview of the campus, it does not divide it, does not force sharp distinctions between humanities and sciences, between undergraduates and graduate programs.

Quiet and orderly, the Quad gives the campus a sense of equilibrium. And, according to Provost Strohbehn, balance is what Dartmouth is all about. "Dartmouth," he says, "has a unique spectrum of programs, an emphasis on undergraduate education and strong graduate schools as well. Our mission is to maintain that unique character... a combination of undergraduate and graduate activity, a balance between teaching and research, not to let the school go too far in one direction." His point mirrors a statement that President James O. Freedman made to the faculty last fall. "This is not a period in which to spend our energies on making Dartmouth larger," he said. "It is a period in which to focus our efforts on making Dartmouth better."

Scott Brown, though, knows that the College will never have a Quad, at least not quite as she has envisioned it. "I don't know of a campus plan that hasn't been abrogated," she says matter-of-factly, without any trace of pessimism. Hanging on the wall of an upstairs conference room in Fairbanks South, which houses the Facilities Planning Office, is a picture that proves her point. The sketch shows the Dartmouth campus, familiar enough at first glance, except that the buildings are more uniform and a grand Georgian structure covers the area now occupied by the Hopkins Center and the Hanover Inn. The sketch is John RussellPope's 1922 master plan for the College; the immense building, his proposal for a student union.

Though never realized in totality, RussellPope's plan for a Dartmouth destined not to exist can hardly be considered a failure. Among other contributions, he sent the campus westward, developing Tuck Mall as a significant offshoot of the central Green. In a campus plan, Scott Brown explains, fulfilling every detail is not what counts. What matters is taking what she calls "that powerful first step," making a decision—like plotting a Green or erecting a Baker Library—that will influence everything that follows.

"It's all very well to have a vision," she explains. "But if you only have that and you don't have a set of steps for getting there, you're never going to get there. The first step is enormously important in setting the right direction. It should have its own powerful identity and character, but also leave a lot of leeway for the future."

Guiding Scott Brown's vision for Dartmouth are the "powerful first steps" that have preceded her, the myths and memories and mission statements, embodied in the buildings and grounds, that together give Dartmouth its character. Scott Brown is working to extend rather than usurp Dartmouth's traditional image. That she understands the significance of tradition is clear in the illustration she chose as the frontispiece for her interim report on the Concept Plan: the famous engraving of Wheelock and his students under the trees.

She also understands that tradition is not static. "The elements of [Dartmouth's] image," she wrote in one of her preliminary reports, "play a major part in the identity of Dartmouth, yet their role has changed with time and is changing still today."

The image of the wilderness is a case in point. These days the wilds of northern New Hampshire seem relatively safe compared to the urban angles of New Haven or Philadelphia. Dartmouth's campus, with its open, unprotected Green, reflects a sense of security. There are no enclosing walls as at "Fortress Yale," no turning inward, away from the surrounding town. "The campus reflects a more rural, less congested, more reflective atmosphere," observes Strohbehn.

Eleazar Wheelock himself saw Dartmouth's rural, reflective atmosphere as a strong point. So did William Jewett Tucker. Those words meant something quite different to the eighteenth-century missionary than they did to the late nineteenth-century educator or to the late twentieth-century administrator. In 50 years, even if future Dartmouth leaders expand the College, its campus should still be embodying those values. What the traditional images will mean, though, is not so easy to predict or control.

A place lying in the wilderness,at least as seen from Vermont."Better, not larger" is the mottoplanners are using to determinethe institution's future.

The Venturis made awry and affectionatebow to College traditionwhen they designedthe Thayer addition.

While other campuses seem romantic or secretive, the austere Green and unified buildings at Dartmouth express satisfied self-confidence.

The planner: architectDenise Scott Brown.

The plan-or, rather,one of the plans, left.Campus officials favorthis vision of the areanorth of Baker, whichwould eventually take oncharacteristics of,a NewEngland mill town. TheGerry-Bradley mathcomplex, above, followedshorter-range goals.

Believe it or not, theBema almost ended uplooking like this.

A writer who specializes in design and architectural issues, Ann de Forest lives in Philadelphia.

"Physically, thevisually chaoticnorth end ofcampus canfinally haveform andidentity

"The situation,for Dartmouth,has been a littlelike winning thelottery"

"The DuckPondplan,whimsicallynamed andconceivedwould havecreated a birdsanctuary inthe middle ofcampus"

"These days thewilds ofnorthern NewHampshireseem relativelysafe comparedto the urbanjungles ofNew Haven orPhiladelphia.

"Scott Brownis working toextend ratherthan usurpDartmouth'straditionalimage."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Ann de Forest

Features

-

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Hold Annual Meeting

DECEMBER 1972 -

Feature

FeatureWorlds Together

SEPT. 1977 -

Feature

FeatureEVEN DISAGREEING WITH HIM WAS PLEASANT

May 1955 By ARTHUR H. LORD '10 -

Feature

FeatureKiewit: A Man-Machine Success Story

APRIL 1972 By Charles J. Kershner -

Feature

FeatureWDCR Reports

MARCH 1968 By LAURENCE G. BARNET '68 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Sept/Oct 2006 By Russell Hardy' 62