IT is toward the end of Freshman Week, a warm and balmy afternoon typical of mid-September, and lounging on the steps of one of the dormitories are the usual small groups of. green-and-white-hatted young men chatting about their first days of life at Dartmouth. Most of them, as might be expected, still look a little dazed by it all, but standing by himself over to one side is one who looks even more bewildered than the others. He shuffles awkwardly from one foot to the other and is obviously surprised when one of the other .young men walks over and introduces himself. A shy smile crosses the young man's face and he answers back in broken, uncertain English, groping here and there for the correct word. He still seems to be a bit ill at ease, but the wide and friendly grins from other freshmen standing nearby soon start to dispel such feelings. They also start talking to the young man, consciously making it a point to speak slowly and clearly, and of course someone inevitably ends up asking his new friend about his first impressions of the United States.

It hadn't taken them long to identify him as one of the dozen or so foreign students entering Dartmouth with every freshman class. He is undoubtedly a little overwhelmed by these new surroundings at first, but if he is anything like the vast majority of foreign students who have come before him he will rapidly adjust to college life, benefiting by his presence both himself and his fellow students. An important part of the Dartmouth educational experience has always come from the "impact of youthful mind upon youthful mind," as President Emeritus Hopkins used to describe -it; and here is a perfect example of the opportunity offered young men of diverse backgrounds and geographical origins to live together on terms of social intimacy and broadened understanding.

As a matter of policy the College has long striven for a wide geographical distribution of students from all the states, and a logical extension of such thinking has led to the matriculation of an increasing number of qualified students from other lands. However, foreign students are by no means a novelty to the Dartmouth scene. The college catalogue of 1859-60, one hundred years ago, records two, one from Ireland and one from England. Fifty years ago, in 1909-10, there were three, from Mexico, France and Egypt. As time went on the number crept up gradually, but it was not until after World War II when regular exchange and foreign student programs were instituted by the federal government and private foundations that any sizable number arrived on the campus. The yearly average enrolled during these recent years, from 1945 until the present, has been roughly forty, more than double the yearly average prior to the war.

The students themselves come from every part of the world, but in the past decade or so the largest national groups have come from France, Norway and Japan. The large delegation from Japan can be traced principally to the fine work of the College's notably active alumni group in Japan and also to the influence of the Mitsui family, which has a Dartmouth representative in almost every generation.

The prospective foreign student may gain admittance to the College in two principal ways. He can either apply directly, which is quite often the path taken by those who can pay their own way, or else his name may reach the Admissions Office on a list sent by the Institute of International Education in New York, which serves as a clearing house for qualified foreign students needing scholarships. At present about half of those enrolled in Dartmouth are receiving financial aid from either the College or an outside agency. A very specialized third path by which one foreign student a year may arrive is through the National Student Association (NSA). In this program a man who has been active in student government in his own school in a foreign country spends a year on the campus in a special status, possibly taking a few courses, but primarily observing American forms of student government as practiced here at Dartmouth.

In any case, th& Admissions Office must devote a great deal of personal attention to each application to determine if the man is thoroughly capable of carrying the academic workload. Naturally the greatest single hazard is the applicant's proficiency in English. There are several testing methods available and among the best are the regular College Board exams in English, but none of them is infallible at best, and then it is always possible that a prospective student from a remote area would not be able to take them.

Checking upon character, so to speak, can be another tricky task. For there have upon occasion been unpleasant cases where foreign students admitted to Dartmouth, and many other institutions for that matter, turned out to be so-called "handlers," taking the College and everyone else for all they could. But of course these are strictly the rare exceptions, and as anyone in a dean's office will readily testify, there is no shortage of native American students whose ventures, though probably less publicized, are equally if not more questionable. With it all, however, and despite the varied problems involved, the admissions officers have been steadily gaining experience in such matters related to foreign applicants, so that anyone admitted today is sure to be a pretty promising prospect.

ONCE in Dartmouth, the really big hurdle, both academically and socially, for the average foreign student seems to be the first year - the same again being true of course for many of their American brethren. Away from trusted and familiar surroundings many become homesick and discouraged. This has been found especially true of Asian students, who come from lands where the family is closely knit and all-important and then suddenly are cast into a situation where they must depend entirely upon themselves.

However in these early moments of extremity they are not without helping hands. Directing the foreign student program and acting as liaison man with immigration and scholarship authorities is Prof. Herbert R. Sensenig '28 of the German Department. What is more important, in addition to his administrative duties he serves as adviser, friend, father confessor, or just about anything else the individual situation might require. Even before the regular school year has begun, he has gathered together all of the new foreign students for a picnic on his farm in Norwich. There they get a chance to feel that they are really welcome in someone's home and family. They meet others who, like themselves, feel alone and apprehensive, and they can take comfort in this newly found companionship. There are many others who help out also. Professor Sensenig cites the especially fine work of the Sophomore Orientation Committee, Green Key, and the Dartmouth Christian Union, among others, in easing the newcomers' integration into Dartmouth life. Another prime consideration for those who are involved with the foreign student

program is insuring a maximum academic adjustment in the first year. Since most problems here can be traced to language difficulties, a special English 1 section has been set up under Mrs. Sensenig to help those who need it. Beyond this, professors in other courses usually try to be understanding with those having such tribulations and some will give the foreign student a special examination and extra time in which to take it. It has been found that a real killer is the multiple-choice, machine-graded exam, which almost always employs fine differentiations of words and meanings. Where-ever possible in these cases, an essay exam is now substituted for the foreign student.

In the nebulous realm of social relations, all but the most sophisticated foreign students are bound to lack confidence at first and sometimes feel drowned in a sea of strange faces. But this usually doesn't last too long. Reportedly the Dartmouth student body has recently been taking an increased interest in getting to know its foreign members here on campus. Social mingling is now very common and quite a few foreign students have been taken into fraternities in sophomore year. Fortunately Dartmouth is small enough that they don't get lost; nor do they tend to congregate into unassimilated national groups, as so often happens in larger schools.

On occasion, roommates and dormitory living can present their own kind of problems due to differences in habit, age, and temperament; but there has been surprisingly little friction of a serious nature, and that which does occur can usually be solved by simply moving the student to another room. An attempt, though, is generally made to put foreign students in double or single rooms in order to avoid at all costs the possibility of placing one in the intensely lonely situation of being outnumbered and ignored, as could easily happen in a triple. A similar touchy situation, according to Professor Sensenig, is that many foreigners are often not able to differentiate between an American's idea of "friendliness" and

"friendship," attitudes that they may very well consider identical. Some have occasionally been hurt by this lack of mutual understanding; but here again, as with most of the other problems facing foreign students, time and experience are the best cure.

As the first few difficult months are managed somehow and the foreign student gains assurance and poise, he is in a position to take maximum advantage of what Dartmouth has to offer and in return make his own definite contribution to it. He can hardly help broadening •the-horizons and understanding of those about him, and into the classroom he brings his own fresh and singular point of view. What could be more stimulating in a history or government class, for example, than to hear an Asian or African student discuss his country's political situation from first-hand experience? Or perhaps it could be a dormitory bull session where one could hear about methods and forms of student life and education so far from customary American standards as to give second thoughts to a sensitive listener.

Some of these differences can give rise to amusing incidents. One Asian student of several years ago, in whose country it was customary for students to riot at every unpopular turn of political events, was constantly trying to rouse his Dartmouth classmates into street demonstrations over local and national issues. Needless to say, he had little success, but it took quite a while to convince him that his American counterparts entered into such activities only when aroused over small green headpieces or sundry articles found only in co-ed dormitories.

Beyond the cosmopolitan and classroom aspects, there have also been foreign students who have left a definite mark upon both their classmates and the College. One need go no further than the valedictorian of two years ago, Jaegwon Kim '58, of South Korea, truly one of the outstanding graduates of any year. In athletics, the rugby and soccer teams have always been strongly bolstered by foreign students playing what in some cases was their national sport. For another, what better example is needed than Chick Igaya '57, the Olympic skier? And while on skiing, there is hardly a year when some part of the ski team roster doesn't sound as if it could belong to the University of Oslo.

In all phases of Dartmouth life, these are young men who have a definite contribution to make. And, what is certainly more essential, they have something to take home with them - a broad liberal arts education, often not available in their own countries; a better understanding of America and its peoples; and four years they will never forget.

From his many years of experience and the letters he receives from some of his past proteges, Professor Sensenig feels that the average foreign student is happy at Dartmouth. "When they leave," he states, "I think they realize that they are leaving something they have grown to love."

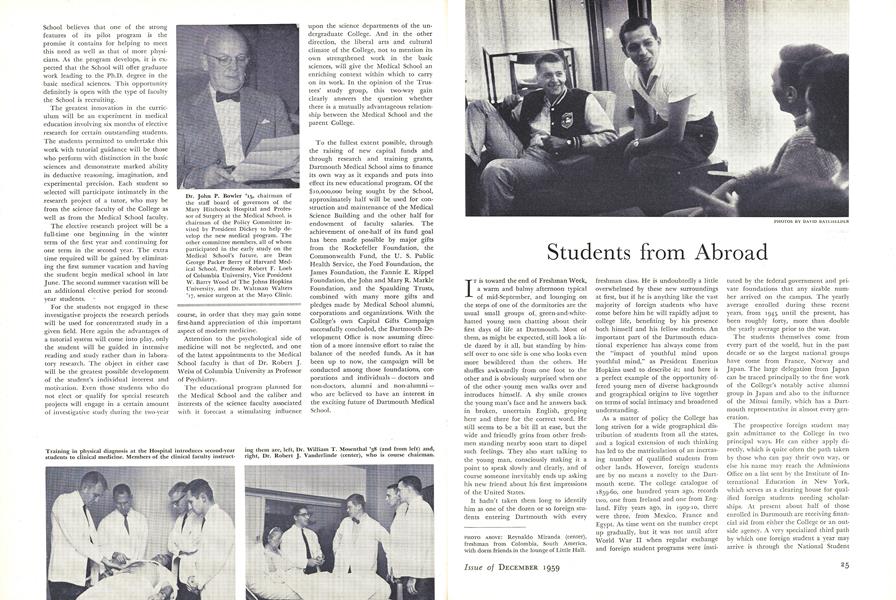

PHOTO ABOVEPHOTO ABOVE: Reynaldo Miranda (center), freshman from Colombia, South America, with dorm friends in the lounge of Little Hall.

Special student Henryk Sokalski from Poland in a history class.

Nitya Pibulsonggram '62, Thailand, makes use of the Tower Room.

Charles Balas '61, a former Hungarian refugee, works a noon shift in Thayer Hall.

Norwegian Einar Kloster '59 meditates a tricky chess move. He lives in what used to be the Graduate Club.

Raymond Pong '60, Hong Kong, is a regular soloist both for the Glee Club and his fraternity during the annual "hum" contests.

Adel Salman '63, Jordan, manages to find a few free minutes to hear the latest records.

Foreign student adviser, Prof. Herbert Sensenig '28, tries to confer as frequently as possible with his charges. Here he chats with Reynaldo Miranda '63, of Colombia.

Mrs. Sensenig conducts her special English class, which is of vital assistance to those foreign students who are working hard to attain a fuller knowledge of the language.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Metamorphosis

December 1959 -

Feature

FeatureMary Baker Eddy and Dartmouth

December 1959 By JOHN B. STARR '61 -

Feature

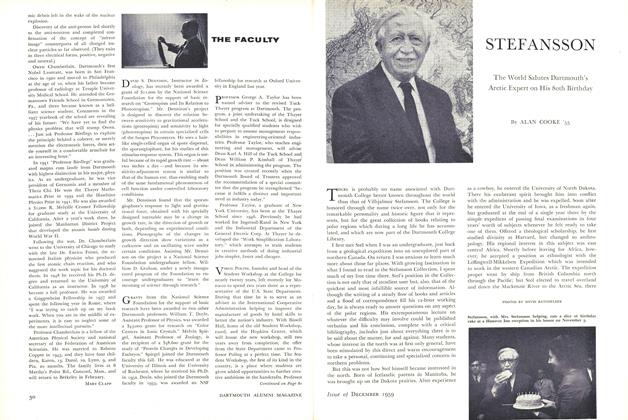

FeatureSTEFANSSON

December 1959 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

December 1959 By JOHN HURD, LINCOLN H. WELD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

December 1959 By CHAUNCEY N. ALLEN, WALDON B. HERSEY

J.B.F.

-

Article

ArticleROTC Adds Winter Warfare Course

March 1958 By J.B.F. -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1958 By J.B.F. -

Article

ArticleHe Taught Hanover What "Hoot" Means

MARCH 1959 By J.B.F. -

Article

ArticleA Way of Life

January 1960 By J.B.F. -

Article

ArticleA Student of the Eskimos

February 1960 By J.B.F. -

Article

ArticleAmateur Sportsman

May 1960 By J.B.F.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe 1961 Alumni Awards

July 1961 -

Feature

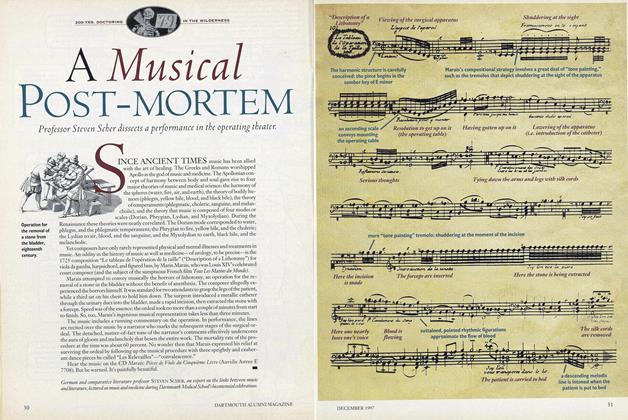

FeatureA Musical Post-Mortem

DECEMBER 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySUNDIAL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

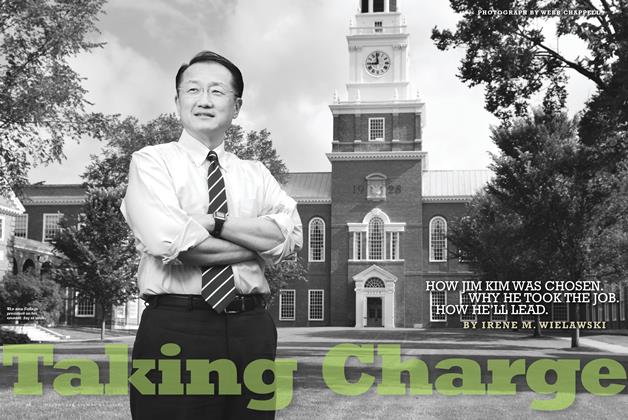

COVER STORY

COVER STORYTaking Charge

Sept/Oct 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2007 By Marrin Robinson '82, Marrin Robinson '82 -

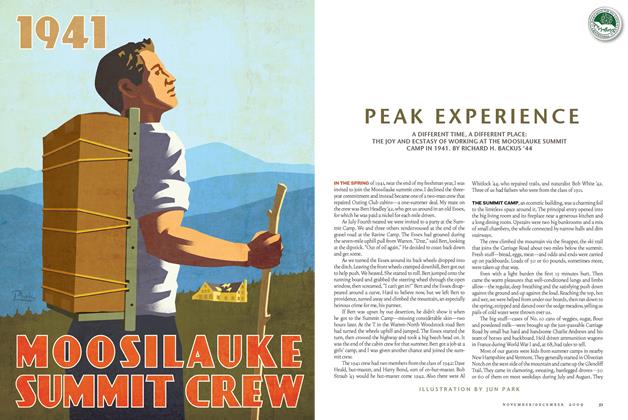

Feature

FeaturePeak Experience

Nov/Dec 2009 By RICHARD H. BACKUS ’44