What do professors do all day?

Dear Professor Navarro: I am delighted that you are willing to be my subject for an article on a day in the life of a professor. What I would like to do is follow you around one day next week. If I had my druthers, I would come to your Home at breakfast time and stick to you like burdock until supper time. . . .

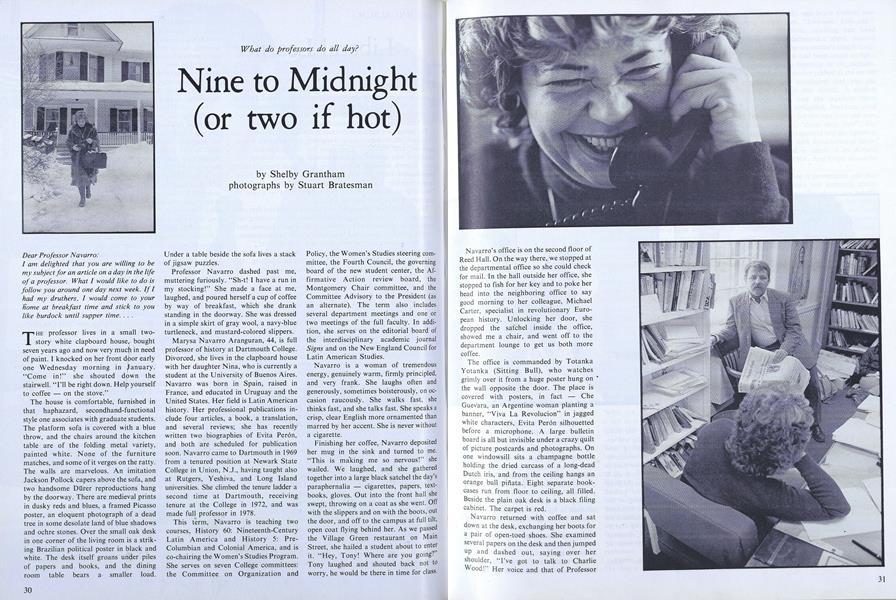

THE professor lives in a small two story white clapboard house, bought seven years ago and now very much in need of paint. I knocked on her front door early one Wednesday morning in January. "Come in!" she shouted down the stairwell. "I'll be right down. Help yourself to coffee - on the stove."

The house is comfortable, furnished in that haphazard, secondhand-functional style one associates with graduate students. The platform sofa is covered with a blue throw, and the chairs around the kitchen table are of the folding metal variety, painted white. None of the furniture matches, and some of it verges on the ratty. The walls are marvelous. An imitation Jackson Pollock capers above the sofa, and two handsome Durer reproductions hang by the doorway. There are medieval prints in dusky reds and blues, a framed Picasso poster, an eloquent photograph of a dead tree in some desolate land of blue shadows and ochre stones. Over the small oak desk in one corner of the living room is a striking Brazilian political poster in black and white. The desk itself groans under piles of papers and books, and the dining room table bears a smaller load. Under a table beside the sofa lives a stack of jigsaw puzzles.

Professor Navarro dashed past me, muttering furiously. "Sh-t! I have a run in my stocking!" She made a face at me, laughed, and poured herself a cup of coffee by way of breakfast, which she drank standing in the doorway. She was dressed in a simple skirt of gray wool, a navy-blue turtleneck, and mustard-colored slippers.

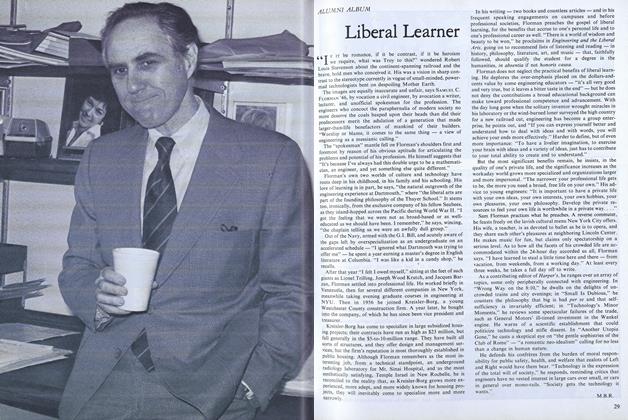

Marysa Navarro Aranguran, 44, is full professor of history at Dartmouth College. Divorced, she lives in the clapboard house with her daughter Nina, who is currently a student at the University of Buenos Aires. Navarro was born in Spain, raised in France, and educated in Uruguay and the United States. Her field is Latin American history. Her professional publications include four articles, a book, a translation, and several reviews; she has recently written two biographies of Evita Per6n, and both are scheduled for publication soon. Navarro came to Dartmouth in 1969 from a tenured position at Newark State College in Union, N.J., having taught also at Rutgers, Yeshiva, and Long Island universities. She climbed the tenure ladder a second time at Dartmouth, receiving tenure at the College in 1972, and was made full professor in 1978.

This term, Navarro is teaching two courses, History 60: Nineteenth-Century Latin America and History 5: Pre-Columbian and Colonial America, and is co-chairing the Women's Studies Program. She serves on seven College committees: the Committee on Organization and Policy, the Women's Studies steering committee, the Fourth Council, the governing board of the new student center, the Affirmative Action review board, the Montgomery Chair committee, and the Committee Advisory to the President (as an alternate). The term also includes several department meetings and one or two meetings of the full faculty. In addition, she serves on the editorial board of the interdisciplinary academic journal Signs and on the New England Council for Latin American Studies.

Navarro is a woman of tremendous energy, genuinely warm, firmly principled, and very frank. She laughs often and generously, sometimes boisterously, on occasion raucously. She walks fast, she thinks fast, and she talks fast. She speaks a crisp, clear English more ornamented than marred by her accent. She is never without a cigarette.

Finishing her coffee, Navarro deposited her mug in the sink and turned to me. "This is making me so nervous!" she wailed. We laughed, and she gathered together into a large black satchel the day's paraphernalia - cigarettes, papers, textbooks, gloves. Out into the front hall she swept, throwing on a coat as she went. Off with the slippers and on with the boots, out the door, and off to the campus at full tilt, open coat flying behind her. As we passed the Village Green restaurant on Main Street, she hailed a student about to enter it. "Hey, Tony! Where are you going?' Tony laughed and shouted back not to worry, he would be there in time for class. Navarro's office is on the second floor of Reed Hall. On the way there, we stopped at the departmental office so she could check for mail. In the hall outside her office, she stopped to fish for her key and to poke her head into the neighboring office to say good morning to her colleague, Michael Carter, specialist in revolutionary European history. Unlocking her door, she dropped the satchel inside the office, showed me a chair, and went off to the department lounge to get us both more coffee.

The office is commanded by Totanka Yotanka (Sitting Bull), who watches grimly over it from a huge poster hung on the wall opposite the door. The place is covered with posters, in fact - Che Guevara, an Argentine woman planting a banner, "Viva La Revolucion" in jagged white characters, Evita Peron silhouetted before a microphone. A large bulletin board is all but invisible under a crazy quilt of picture postcards and photographs. On one windowsill sits a champagne bottle holding the dried carcass of a long-dead Dutch iris, and from the ceiling hangs an orange bull pinata. Eight separate bookcases run from floor to ceiling, all filled. Beside the plain oak desk is a black filing cabinet. The carpet is red.

Navarro returned with coffee and sat down at the desk, exchanging her boots for a pair of open-toed shoes. She examined several papers on the desk and then jumped UP and dashed out, saying over her shoulder, "I've got to talk to Charlie Wood!" Her voice and that of Professor Wood, who chairs the department, drifted back down the hallway, Navarro's wheedling and Wood's resisting. In the end, Wood capitulated to Navarro's request to have the department pick up the tab for the lunchtime meeting of the Third World historians. There was a whoop from Navarro and a shout from Gail Patten, the departmental secretary and budget hawk: "Don't authorize it, Charlie! They'll go to Jesse's!"

Navarro came running around the corner like a kid on the lam, grinning from ear to ear. "Gino!" she shouted into an office down the hall from her own. "Gino! He said yes - as long as we don't spend more than $4 each." "Let's go to Jesse's, then," replied Professor Gene Garthwaite. "The Bull's Eye is so boring."

Back at her desk, Navarro did some serious class preparation, reading and underlining in a text and pulling and rearranging a series of large notecards. After a while, Garthwaite, whose field is Middle Eastern history, strolled in to ask if she had seen the CBS program on the Shah of Iran. "I was really upset with it," he told her, hiking up one leg and perching on the arm of a chair. The two of them discussed the program at length and speculated on the political situation in Iran. As Garthwaite left, Professor Leo Spitzer, specialist in the history of Africa, arrived at Navarro's door.

"Hello, baby," said Navarro. "What have you been doing?"

"Oh, I've been reading the letters."

"You've been reading them since last Sunday! That's all you do these days."

Navarro and Spitzer chatted for several minutes about' Spitzer's research for a book on assimilation and self-identity in crisis, for which he is going through the papers of an Austrian poet. After checking to be sure that the Third World scheduling meeting was still on for noon, Spitzer returned to his office and his letters, and Navarro turned again to her lecture notes.

At 9:30, Carter dropped in to say that Women at Dartmouth was staging TheYellow Wallpaper at noon at the new student center.

"The Third World group is meeting today at noon to do schedules for the next two years," said Navarro. "Have you people done your scheduling?"

"Yes. Want to go to The YellowWallpaper on Friday, then?"

Navarro checked a little black diary and said yes.

"I'll bring some fried chicken so you won't have to eat the wholesome food at the center," said Carter as he turned back toward his own office.

"Michael," Navarro called after him. "Can I make reservations on Amtrak?"

Carter turned on his heel, saying, "That's such a ridiculous train. You can fly to New York for $49. One way, $25. New thing. Saw it in the Valley News. It would save you six hours and cost only two bucks more. Call this 800 number." Carter looked up a number in Navarro's directory and, handing it to her, departed, saying, "I've got to go. I've got several monarchs to depose today."

Navarro made her reservations and shouted, "Fantastic! Michael, you're a genius."

"Stick with me, baby," Carter shouted back.

Navarro then made another call, to the New York editorial offices of Signs, to say that she would be coming to the meeting on Saturday. Signs did not answer. She made a few changes on the notecards with a fountain pen, checked the time - 9:55 - and then gathered the cards into a folder and put it in her satchel. She had a hurried last sip of her cold coffee, grabbed a paperback copy of Spanish-American Revolutions,1808-1825, and headed downstairs for the first class of the day.

IT is not a very inspiring place, the tiny yellow classroom where History 60 meets. The carpet is gray, the desk is small and battered, the little framed bulletin board high up on one wall is blank. A standing map of Hispanic America is crowded into one corner, blocking the window, and there is a blackboard on the front wall. The 16 students taking Nineteenth-Century Latin America were jammed together in a clutch at the back of the room, waiting for Navarro, who appeared just as the bell died.

She moved the desk center front and put on it an ashtray fished out from the windowsill behind the map. She pulled four of the chairs with little writing arms into a line at the front of the room and took the one next to the desk herself. "Okay. Who is supposed to be up here?" she asked, waving at the empty chairs beside her. Three students detached themselves from the clutch and took the chairs.

"Did you decide," Navarro asked them, "what are the two fundamental questions to ask in order to understand the Mexican independence movement?"

The three students responded, and Navarro inquired of the class as a whole how it felt about their questions. A student whose point of view was challenged insisted on it at length, drawing a laugh from Navarro: "Wait a second! I am supposed to be the stubborn one here. Everybody knows that I am stubborn - but you are being more stubborn than I." Another student, tangled in an explanation which went on too long for clarity, was stopped by Navarro; "You lost me. I don't understand what you said." The student backed up and rephrased.

At one point, Navarro asked the class, "Is that a legitimate statement?" No one answered. Finally, one brave student ventured a faint yes. "Unh-unh! Unh-unh!" exploded Navarro, shaking her head solemnly. She delivered a short, pointed explanation of the statement's illegitimacy. The cigarette she had been about to light, forgotten in the intensity of the explanation, became a pointer jabbed at the air for emphasis. She concluded and put the cigarette back in her mouth. A student challenged her, and the cigarette came back out, still unlighted. Navarro cited further evidence for her analysis and concluded urgently, "Deal with this!" She pointed both the cigarette and the lighter at the class. "Deal with this enormous diversity Mexico had in terms of its cultural composition in 1808. And forget about the Spaniards."

Navarro's voice is penetrating and stirring, and she speaks with shattering clarity. There is no question about the importance of her subject. Her tone, her intensity, her conviction preclude such questions. Occasionally, her own involvement trips her up and she stutters, repeating a single word insistently while she searches for the most accurate word to follow it.

Under her tutelage, arguing, explaining, discussing, the class hammered out an analysis of the Mexican movement for independence. When Hidalgo and the criollos, the cabildos and the church, the preventive coup and the Plan de Iguala had been examined to Navarro's satisfaction, she relaxed, leaning back in her seat with a sigh of exhaustion. "Are we satisfied, then, with Mexico?" she asked. The class seemed to be. "Now, who is doing Venezuela?"

"Nosotros here," said a student, speaking for himself and a fellow.

"Okay, nosotros there," said Navarro. "What are the questions on Venezuela?"

"Well," began the student, "first, let's take a look at the map over here provided by the History Department - "

"God bless it," intoned another student.

"Forever," added Navarro with a grin.

The two students made their presenta- tion and 19th-century Venezuela was in its turn examined. The bell interrupted the discussion, and Navarro dismissed the students, promising to continue with Venezuela next session. The ten minutes between her back-to-back classes were largely taken up by questions and comments put by the departing History 60 students, from which Navarro broke free for a hasty dash upstairs to the women's room before convening History 5 at 11:00.

Pre-Columbian and Colonial America meets in a somewhat more spacious room than does History 60. It is a freshman course, in which Navarro lectures to the students, 23 of them, instead of leading discussion among them. And she stands rather than sits for it. She began with a procedural announcement about some outside reading: "Who wants to read Cortez's own account of the fall of Mexico and who wants to read the account written by one of his foot soldiers?"

There were mumbles and raised hands and cries of "foot soldier." Only a few students volunteered for Cortez. "Hey," said Navarro. "I need people to do Cortez. They're both fun. If your idea of fun is reading 16th-century documents, that is." She laughed. "And they're in English. Thanks be to the Holy Ghost that they have been translated into English.': In the end, professorial fiat was invoked, and the class was divided half and half into Cortez readers and foot-soldier readers.

Navarro began her lecture, keeping a tight rein on questions and digressions in order to be sure she covered the day's material. She painted a vivid picture of Aztec society, touching on Aztec religion, the Flower Wars, the diseases brought by the Spaniards, the process of Moctezuma's deification, the desperation of Moctezuma.

"Now," she concluded, "are there any questions before we cross, the Panama Canal and go to Peru?" There were not, and Navarro began to describe the Incas - more properly, the Tahuantinsuyu. After a long and evocative description of the bleak geography of most of the land of the Tahuantinsuyu, a student was moved to ask why the Spaniards wanted to conquer such a miserable area.

"Aha!" cried Navarro. "Aha! You will see!" She stubbed out her cigarette against the inside of the trashcan and began a detailed account of the various cultures which preceded the Inca Empire. Mochica,Paracas, Tuahuanaku, Nasca, Sapa Inca, and other terms had to be explained and spelled out on the blackboard in the course of the lecture. Navarro wrote and erased, wrote and erased, until the blackboard was awash with strange words, architectural sketches, and lost-language diagrams.

Her last topic was the artwork of the cultures, and her concluding remarks were directed to the student who wondered why the Spaniards bothered with the Incas. "With this culture," said Navarro, drawing out her words dramatically, "with this culture occurs the first sign of - gold!" Her final sentence was an avaricious hiss. "Large quantities of beautifully worked gold', the palace of Sapa Inca in Cuzco was covered inside with gold."

Navarro dismissed the class and returned to her office to make a quick telephone call about the date of the next meeting of the Fourth Council. As she hung up, Garthwaite and Spitzer, together with Professor John Major, historian of China and Japan, appeared at her door. "Come on," said Navarro, taking two of them by the arm. "The Third World is eating!" "Where are we going?" asked Spitzer. "The Inn," replied Navarro. "He'll kill us."

AT the Hanover Inn bar-restaurant, they chose a large round table and ordered. Navarro, Spitzer, and Major settled on eggs Benedict and white wine, with coffee afterward; Garthwaite opted for onion soup and a Reuben. Then they spread out their scheduling drafts all over the table, and Navarro took charge of filling in the blank boxes on the master schedule.

"Does everybody have this thing - the paper Gail gave us?" she asked. "John, do you have a course catalogue?"

"Leo brought it," said Major.

"I brought a pencil," said Navarro. "Now. Gino. Is this your introductory course here?"

"Yes. I term-traded, so I have to teach in the summer of 1980."

"I know I have a vacation here," mumbled Navarro, putting a large X in one box.

"Don't forget about 63 and 95," Major warned.

"Let's see," said Navarro, busily filling up boxes with Xs, "Garthwaite...Major . . . Spitzer ...Navarro...Erdman. Erdman. Is Erdman doing 63 in the spring?"

"Not next year," said Garthwaite. "He's going to India."

Suddenly, Navarro sat back in puzzlement, frowning at the schedule before her. "Why am I teaching six courses instead of five? Why do I have an overload?"

"Marysa," said Spitzer with exaggerated patience. "The year starts in the summer."

"Oh - yes. You're quite right," said Navarro. "Leo, what is your 94?"

"Seminar," replied Spitzer. "Senior seminar."

"Okay," said Navarro. "We're done. Oh - hey. I have summer schedule here. That's like Monday and Thursday - and I can get the hell out on Friday! And have long weekends!"

"She only lectures a third of the time, anyway," said Garthwaite with a vast shrug.

"Jeez!" said Navarro.

"And Leo only does two-thirds - we know that," added Major.

"Baloney," said Spitzer.

"If this goes through it will be the first year we haven't had a second meeting," said Navarro, stealing a potato chip from Garthwaite's plate.

No one ordered dessert, and coffee conversation rambled from the imminent arrival from Persia of Navarro's new Persian cat to snow problems with roofs and how many paella dinners Navarro owes Garthwaite. The check came and Navarro signed it. "Hey, people," she said. "We're $4 over."

"It's all right," said Major. "Gail won't get the bill till next month and she will have forgotten by then."

As the group gathered coats and papers, Spitzer described to Navarro a New World course under consideration by one of the College programs. Navarro's face clouded as she listened. When Spitzer finished, she said, "I think that s- -ks. Courses like that are so shoddy."

"Well," prompted Spitzer, "call Al up and tell him that. We're meeting this afternoon about it, and you're the one who ought to judge the course. It's your field."

"I will," said Navarro.

Back at Reed Hall, Navarro gave the master schedule to Patten and returned to her office, where she picked up the telephone and dialed an intercampus exchange.

"Hello, Al?" she said. "How are you? Listen, Al, I wanted to talk with you about a course that Leo Spitzer reported to me is being contemplated by your program, which makes me very nervous. My reaction when Leo described it was that it s- -ks. I know that is not very academic, but that's the best expression I can find to describe that course. And it's going to be taught the same way I teach that same course in the History Department. What? No, no, no, no. My course doesn't s- -k. It's the same topic, I mean, and it's going to be taught the same term."

Navarro listened a while and then replied, "I understand that. I feel uneasy about talking to you, Al, because it's not my right to interfere. I'm calling because Leo said I should. Mmmm. Feudal lords in Peru? Jesus. It's a pot-pourri, Al! Is that legitimate? Well, I'm glad I have nothing to do with it. No, I don't have a right to try and stop the course, but I think it should not be offered to undergraduates, that definitely. Because I think one has such a hell of a hard time - or I have, anyway - making students appreciate the nature of those societies, their way of life, of seeing things, and the clash that happens when the Spaniards ... exactly! That's my point. It takes them a long time. I don't know how you can do it in a shorter time than I do it, and I cover a third of what this course of yours covers. Okay. On my part, I do wish to apologize, and I do not want to create a bigger problem than ought to be. Certainly not for you, okay? I've told you what I thought. Very good. Okay, Al, I'll let you off. Let's have lunch one day, okay? Very good. Bye-bye."

Navarro put the phone down and picked up a sheaf of printer's proof for her forthcoming article about the women of Argentina, written in cooperation with an Argentine sociologist. She began reading and correcting the proof. Technically, she was holding office hours for students, but since it is early in the term, she had no callers. Later, questions will arise, and at some point the approaching end of the course will cause varying degrees of gradepanic, and students will come to talk or to plead a cause.

The telephone rang again. It was Tamar Riggall, administrative assistant in the Office of Women's Studies. "Oh, Tamar, hello," said Navarro. "Yes, I have it down. 'Women's Studies, 2:00.' Oh, and I have to answer that letter for the Barnard thing. 'Where is the letter?' No! Is it lost? I'll have a heart attack. Is it in my folder of Women's Studies there? Oh, good. By the way, Tamar, my tape recorder is still going eh-uh, eh-uh. We didn't fix it.

"Oh, Women's Studies needs to discuss co-sponsoring Bette Williams, co-winner of the Nobel prize. Her speaking fee is $2,500 flat. Fifty to a hundred is all we can do with our budget, but we should discuss it. You are? What is the film? Oh. No, I want to stay home and write. I have to stay home and write. No, Friday afternoon I am having lunch with an Aymara priest. A Peruvian priest. Tomorrow noon there is a play I want to see. Maybe I can come and sign the paper after the play. Tomorrow the department meeting starts at 5:30 and could go on forever. Fine. See you then."

No sooner was the receiver back in its cradle than the telephone rang again. "Hello," said Navarro. "Oh, David. Yes. I am expecting you here at 3:00 today. We are going to talk about the speaker series, no? Oh, I see. When next week? No, I have a World Affairs seminar then. Later today? Okay. At 5:00 at the Inn bar. See you there instead of here."

At 3:45, Spitzer returned from his meeting and came to report on it. "What did A 1 say?" asked Navarro. "Was he angry?" Spitzer recounted briefly who said what and returned to his own office. Navarro tried unsuccessfully to place another call to Signs on the College's long distance telephone system. On the fourth try, the call went through - but Sign's line was busy.

Navarro leaped up suddenly, announcing, "I'm going to read the Times." In the department lounge, where the day's papers from many cities were spread over a seminar table, she sat with her leg under her, reading, smoking, and drinking more coffee. Colleagues drifted in as the day began to wind down. Conversation ranged from the sociological significance of the center foldout in Playboy to the history of the exclusion of Jews and Catholics from Dartmouth's faculty. At 4:30, several members of the group left for home, and Navarro and Major went back to the newspapers.

Navarro encountered an ad for a historical study using police records. "When I see that I get so envious!" she said to Major. "There is no way for us to do a study like that in Latin America, even for the 18th century. The archives are just so difficult. You wouldn't have a terrible time, would you, John, getting police records? I thought not. I get yellow with envy."

She returned to the office at a quarter to five, just in time to receive a call from the dean of the faculty about the previous day's meeting of the Committee Advisory to the President (CAP). He was calling to apologize for having kept Navarro, who serves as CAP alternate, waiting two hours in expectation of being needed, which, as it turned out, she was not.

AT 4:55, as she reached for her coat to walk over to the Inn bar for the 5:00 meeting, Laurence Radway of Government and David Gregory of Anthropology appeared at her door. None of them really wanted a drink, and they decided to have their meeting in Navarro's office instead. Gregory and Radway are in the process of setting up a speaker series on Latin America and had come to ask Navarro's advice. They also wanted to know whether History would co-sponsor the series and bear a portion of the costs involved.

"How much have Government and Anthropology got?" asked Navarro. "And what would History have, to put in - work on my part, or money?"

"Both," said Gregory. "We were hoping you would be involved substantively this year - in setting up some debates, for instance. Last year's series was dull. We decided we need more dialectic this year."

"Where have you tried for College funds?" asked Navarro.

"What do you recommend?" asked Radway.

"Policy Studies, Public Affairs - you can get $150 out of each," replied Navarro.

"If we could bring in the Orozco murals in the library," said Gregory, "we would have another source of funds."

"Yes," said Radway. "But how do we do that?"

"You know who's at Princeton now?" said Navarro. "Carlos Fuentes - the Mexican novelist. He is a friend of mine. Perhaps I can get him to come."

"What is the connection with the Orozco murals?" Radway asked.

"We ask him to come and say something about them," explained Navarro.

"Hey!" said Gregory admiringly. "You're an entrepreneur. I like that. All they can do is say no."

They lined up some other prospective speakers, and then Radway asked, "What time is the hockey game?"

"I think it's.at 7:30," replied Gregory.

"Jeez," said Radway, looking at his watch. "I've got to go home for supper."

"Yes," agreed Navarro, reaching for her boots. "What about another meeting to finish this? Monday?"

"No," said Gregory, "I'm going to be out of town. Friday?"

"Friday's my birthday," said Radway. "I won't have a meeting on my birthday."

"Wednesday?" asked Navarro. "After the Fourth Council meeting at 3:00? Good."

The men left, and Navarro put on her boots and coat and stuffed some papers into the black satchel. I asked what she would do in the evening, and she explained that she was having a "television invasion" for an hour after supper. On Wednesdays the children of a friend who doesn't have a television set come to Navarro's house to watch The Muppets. "Then I'll write," she said. "I'm going to write in the morning, too, and come in at noon. I don't try to write in the office. There are too many interruptions. I'll work tonight until midnight. Unless I get really hot - then I'll continue until two or so and get up later in the morning."

The Baker bells were ringing six o'clock as we left Reed Hall and began the eight-block walk home. It was dark outside, and Navarro was disappointed to realize that it was too late for her to stop at the delicatessen on Main Street and treat herself to a bagel and cream cheese for supper. "I forgot to defrost something, you see," she explained, as we passed the closed deli. "You got me all mixed up today. Perhaps I'll eat soup and ham tonight - a sandwich, maybe eggs. Something like that. I try to eat a decent meal, one, every day, and I cook it myself. I think that's the very best therapy after a day of work. I love cooking."

Shelby Grantham wrote "The Researcherand the Teacher" in the November issue.She is an assistant editor and staff writerfor the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. StuartBratesman '75, a freelance photographerbased in Hanover, has taken several pictures for recent issues, including AMatter of Perspective" in October.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

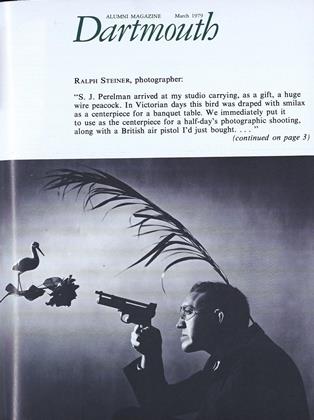

FeatureSTEINER: by himself

March 1979 -

Books

BooksNotes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief.

March 1979 By R. H. R. -

Article

ArticleWinter Carnival Blues

March 1979 By Biĺ Conway '79 -

Article

ArticleLiberal Learner

March 1979 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1979 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1979 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR.

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCANCER

APRIL 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleThe Children's Own Curator

MAY 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

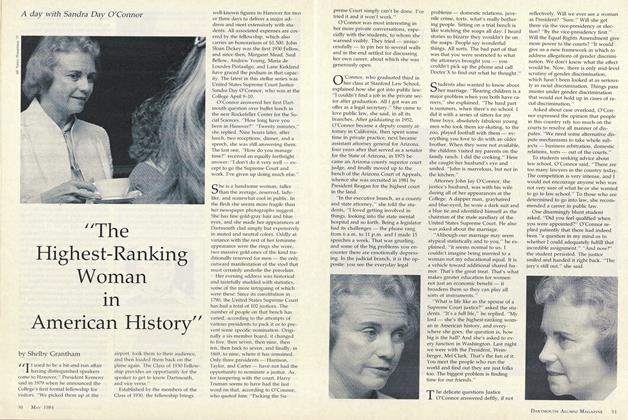

Feature"The Highest-Ranking Woman in American History"

MAY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFourth in a Pig's Eye

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

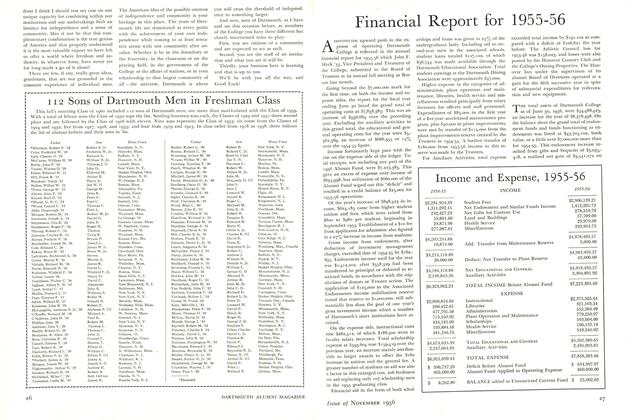

FeatureFinancial Report for 1955-56

November 1956 -

Feature

FeatureOur Way in the World: A Conversation with John Dickey

January 1976 -

Cover Story

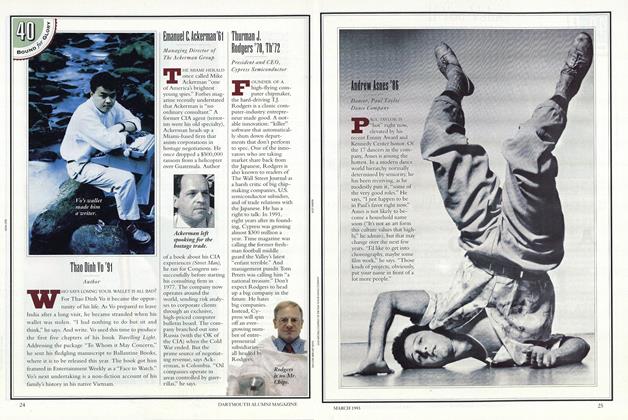

Cover StoryAndrew Asnes '86

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureOf Sun-Gazers and Seal-Hunters

JAN./FEB. 1978 By James L. Farley -

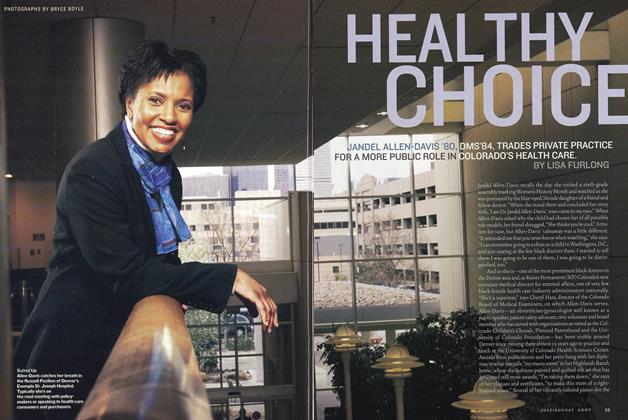

Feature

FeatureHealthy Choice

July/August 2007 By LISA FURLONG -

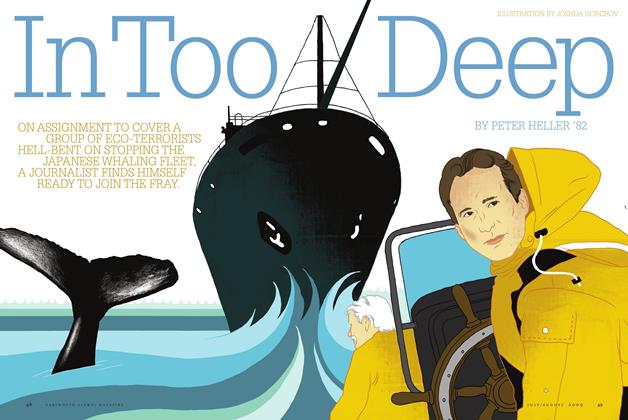

Feature

FeatureIn Too Deep

July/Aug 2009 By PETER HELLER ’82