THE Indians, though nearly always polite about it, get a good deal of amusement out of seeing the whites do something badly. My premier essay at dog-driving was regarded by many as out-standingly tenderfooted, the single pity being that more were not at hand to view it. Like water-skiing, figure-skating and truck-driving, none of which have I ever tried, I was ready to admit that about dog-driving there was doubtless a good deal more than met the eye. However prepared intellectually one may be, the actual experience is likely to be a physical shock. And so this was.

In conversation I had offhandedly agreed to accompany the Mounted Police corporal, Bob Gilham, and his Indian assistant "back in" to a fish lake. I was on Christmas holiday from Fort Simpson, in the Northwest Territories, where I taught school, and had gone down river to Fort Norman to spend New Year's with friends there. Norman is a scenic village of log cabins and frame houses on two terraces where the Bear River joins the Mackenzie. On the other side of Bear River looms Bear Rock, a massive outlier of one of the Rocky Mountain chains. About thirty-five miles behind this was the lake where, every fall, a great number of fish are netted and cached against the winter's needs.

I prudently pointed out my recent inactivity, my total innocence of dog teams, and was reassured to hear that there wasn't much to it, that anyone at all would catch on quite quickly. At die appointed hour of five, still deepest night so near the Arctic Circle, I arrived at the barracks and was plied with breakfast. Then I stood about ineffectually while Victor, the Indian, and Bob bullied large dogs into their traces, ending with three teams of five or six dogs. The animals were hitched in tandem and the sleighs were of the toboggan variety, flush on the ground, provided with a canvas basket along the length and in back a set of handles fixed so as to leave a small area to stand on. A single rope stretched from the curved front of the sleigh back past the handles and to this the wise driver hung as to hope of salvation.

"Now we're all ready. You go last, right after me. When Victor starts off, you loosen that tie rope and just hang on. Going down the two slopes to the river may be a little bumpy. The dogs are always all excited at first, but they slow down pretty quick. Just hang on."

The keening chorus of sixteen dogs, howling and barking in the top pitch of enthusiasm, must surely have awakened everyone in the village. Victor loosed his rope and instantly disappeared over the edge of the bank shouting awesome commands in Indian. "Now let your rope go" shouted Bob, as he untied his.

Quite without any sense of struggle or falling, I instantaneously found myself being dragged at high speed, on my belly, through the powdery snow down the hill. It was too sudden to be surprised, and I simply didn't believe it. After some dozens of yards, my awareness caught up to me and I reflected, as well as possible in such circumstances, what one might say to dogs to encourage them to stop. I was on the point of trying "Whoa!" and to this end was spitting out a mouthful of snow when the sled overturned and my team entered ecstatically into a free-for-all with Bob's dogs.

Cleaning several pounds of snow out of my clothing, I polished my glasses with my fingers, on which the condensation immediately froze into opaque frost, pushed back my parka hood which had fallen over my eyes, and was thinking of taking up breathing regularly once more. Then another lightning discharge of canine energy was effected and we shot down the second slope to the river ice. Clinging to the handles of the sleigh, we slued around a number of corners, impossibly maintaining balance; but, crashing at random into the rough, projecting pieces of broken river ice, I finally lost my grip. The dogs, joyful at being so quickly rid of me, swept up the trail until stopped by Bob, where I caught them in a fever of fatigue and ill-temper.

Re-establishing myself as leech-like as possible, it somehow happened that I kept on the sleigh as it crashed up and down, left and right, along the crazy trail through the jumbled river ice. I cannot remember anything of that part of the trip except that through my frosted glasses I could not see, from the sled handles I dared not let go, and in the 25-below-zero weather my ears had frozen. At last, as into the Promised Land, we entered the woods on the far shore of Bear River and caught our several breaths.

"Well, what do you think of it?" asked Bob.

Having no language to describe my true feelings concerning dogs, river ice. and sledding in general, and believing that flesh and blood could not long endure such battering, I remarked that it was my hope that the rest might prove a little easier.

So it proved to be. As the sun, in the next hours, slowly turned the night into white day, we rode easily along a fair highway through the black-green spruces toward some vague mountains. I presently discovered ways to balance myself standing or sitting, inquired further into the mysteries of vocal direction, and began to believe that a reasonable person could actually take some pleasure in such operations. If cold or stiff, a brief run behind the sled was quickly warming, but having no load the dogs were able to pull us as easily uphill as down. On and on we went, over an initial height which was part of Bear Rock, and then gradually down over lakes and muskegs and through the spruce forest. Late in the afternoon we reached the fish lake and crossed to the far end where the fish cache and a few cabins were.

There we found another Indian, who had come out the previous day for fish of his own and planned to return with us. While we got supper, a bank of clouds which had been threatening since noon overcast the sky, a mournful wind tuned to a higher pitch and presently, as we ate, thick snow began to swirl across our world.

"This snow no good," announced Victor, and we all agreed. "Drift in trail and make it hard to get back," he added. This was true, but there was nothing for it but to sleep well and start early. Bob had brought for supper several tins of food, but the Indians preferred boiled whitefish, large meaty things, full of roe. I ate of both.

We planned to be back by mid-afternoon of the second day, which was the last day of the year, and for this we rose into the frosty night at 4:00 a.m. After our breakfast of fish, tinned meat, bannock, coffee and cookies, the dogs were again harnessed and, four teams now, we silently started. Across the wide lake we skimmed, with nothing above, beyond or below to give any notion of depth or distance, moving swiftly through a sweeping thickness of wind that seemed to hold us and the snow suspended in it. Magically, through the undifferentiated blankness, the trail on the other shore was located and we began the difficult work of breaking it out.

With no load and the dogs fresh, we had had a merry time on the day before, but now, with the sleighs laden with fish, the track drifted, the route largely uphill, and all tired, it was bitter labor. Most troublesome were the lakes on which the packed trail had become a ridge, the unpacked snow on either side being blown away. The sled would slip one way, then the other, into the deep, soft snow, and it took one's full strength and vocabulary to haul it back. The dogs clearly did not believe in me as a driver and refused to work as they should. It quickly became obvious to me why their masters beat them so much (though perhaps it was only what they were accustomed to expect and saw no reason to pull without whipping). At mid-morning, finally exasperated by the condensation on my glasses, I tucked them inside my shirt until a moment could be taken to clean them. You can't stop a dog team just any place, and it was taking all my hands and attention to keep the sled upright. At some point the glasses dropped out, lost forever along the way, leaving me near-sightedly nervous in a world of blurry shapes and shadows.

I had been stiff and tired in the beginning, but that was nothing to the depth of exhaustion gradually achieved, with cramped leg muscles and waves of nausea. During the afternoon we reached the half-way point, a trapper's tent, and there took a few hours' rest. At five o'clock the light was gone, and we continued in the dark. On any day but New Year's Eve, we should have made a camp and stayed the night, but everyone was anxious to get back to Fort Norman for the celebration. Going up the steep ascent immediately behind Bear Rock I let the sled go ahead and tapped my sightless way along the trail with a stick.

Near the top we built a huge fire for tea and roasted a couple of the frozen fish for a lunch. Although the weather had been continually 15 to 25 below zero, with the constant effort and exhortation we were all hot and thirsty. The strong black tea tasted as near nectar as any mortal could hope, and the half-cooked, still partly frozen fish was better than any supper in polite society I had ever tasted. I chortled to think of my friends at home, undoubtedly carousing at that moment of the year's end, and thinking (if they thought of me at all) that I was most likely at that moment examining the floor under some northern table - when all the time I had been slaving the past sixteen hours with a number of perverse dogs and a load of smelly fish.

At last we achieved the top of the trail over Bear Rock and rocketed down the other side to the river. Crash-banging again over the icy river track, we reached the settlement about eleven o'clock. When the dogs had been unhitched and tied in their compound and the fish cached safely away, we sat stiffly on soft chairs in the barracks.

"What will you have to drink?" asked Bob, who had been saving bottles for some time against this festive evening. "Anything you care to name."

One is not often offered such a wide choice in northern settlements. I considered the matter with all the attention it deserved.

"Well," I returned after careful thought, "I never imagined I'd see the New Year's Eve - nor yet the day — that I should say this, but there is nothing I want just now more than a drink of cold water."

And so we drank the New Year in: with lovely long glasses of water, whose delicate taste and soothing coolness assuaged a throat's curseworn roughness, in chairs whose insubstantial softness was a blessing to bruised bones, in a gentle housewarmth which made all memory of the day's harsh winds seem unreal. It was a moment of deepest pleasure, reward enough for the day's labor, the most delightful of my New Year's Eves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN, -

Feature

FeatureCan Chinese Civilization Survive Communism?

November 1959 By WING-TSIT CHAN -

Feature

FeatureSocial Responsibility in Painting

November 1959 By CHARLES T. MOREY, -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

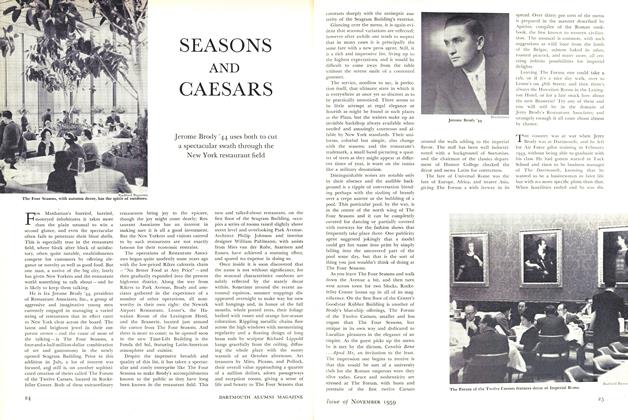

FeatureSEASONS AND CAESARS

November 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Feature

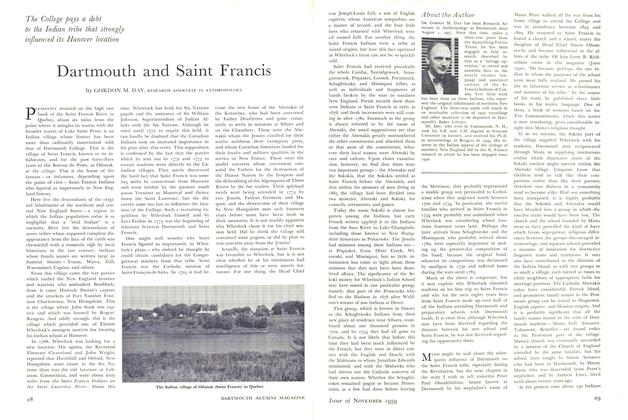

FeatureDartmouth and Saint Francis

November 1959 By GORDON M. DAY