IT was a dilly," said Captain Gaudreau, speaking of the riot which broke out in Thayer Hall the night Dartmouth triumphed over Princeton for the Ivy League football championship.

Whether as responsible authorities or as part of the uncouth, howling mob of undergraduates, all concerned agree that the riot was a beautiful thing, as riots go. It sprang from a mood of jubilant hysteria; Dartmouth's last championship was won long ago, time out of mind for most of us at the College now. And not only was it generated from an achievement to be proud of, but this riot's start could not be traced to any of the more common collegiate ills which undergraduates usually protest against, such as poor food or Saturday classes. Its growth seemed entirely spontaneous, and before very long, all kinds and consistencies of food were being tossed through the air with wild abandon. However, a tinge of disrespect for those in charge of Thayer Hall could be discerned in the general fervor as the riot reached its peak, and soon all control over the boys was lost for a short time.

To tell the truth, the College authorities did not seem to anticipate what the student body's reaction would be if the football team won. Some unkind upperclassmen have gone so far as to suggest that the College did not even take the possibility of winning into account. But, all in all, probably it is fairest to say simply that the Campus Police were understaffed that Saturday evening, and that they could do only so much and no more. Of course, their duties were somewhat complicated: they couldn't really be expected to come to Thayer Hall immediately, since they first had to cope with a fire right in the middle of the street at the Inn Corner. What's more, before the night was over they had had to look after great paper streamers and other litter strewn all the way down Main Street, as well as some $700 damage to the town.

In Thayer Hall itself, approximately $1800 worth of damage was done before the riot was finally quelled. Such a costly exuberance of school spirit might be forgivable, perhaps, depending on one's age and attitude toward the property of others. But, though some might try to shrug or laugh it off, most undergraduates realize that the damage was unnecessary.

The riot was not the quiet, more gentlemanly conduct the College expects from its students, but who could feel guilty at the time? No one, I think, was truly ashamed of overstepping the bounds of seemingly justifiable elation. It was not as if in carping against some College policy, the boys had done malicious wrong. And when the administration asked Palaeopitus to recommend a penalty, and it had called for College warnings to be given to those more prominently involved, 96 were handed out and, we may assume, taken willingly, since the only way to determine fairly who had rioted was to ask the boys to come forward of their own accord. Doubtless many felt it had been worth it.

At present, that large bill still exists and restitution remains to be made. On January 5 Palaeopitus met to discuss ways of paying for the damage, and its chairman, Kurt Wehbring '59, scotched the best idea at that date, a student tax, as "impractical" since so many undergraduates had been out of town at the time.

Voluntary donation may be the only fair way: it would call upon school spirit, to be sure, but of a less riotous kind - the willingness to assume the responsibilities which go hand in hand with the privileges of cheering for and belonging to Dartmouth. This sort of spirit is nothing less than a mature evaluation of one's own particular relationship to the College - an individual moral judgment for each student - and the desire to fulfill the obligations involved.

Surely it would be a rare group of freshmen who could in a body actually feel responsibility to the degree of acting upon it. In fact, I'm sure, as a senior, that many of us even after four years at Dartmouth will not truly recognize our self-defined duties to others until we've spent more than a few years in "the wide, wide world."

If such a lack of this important kind of spirit is the case, as it seems to be, then perhaps it is in order to ask if its inculcation is somehow deficient.

THIS question was precisely the one posed by the Academic Committee of the Undergraduate Council as it reviewed the Freshman Orientation program.

The committee was concerned about the state of apathy and ignorance most freshmen go through, and found it could be partly attributed to certain defects in their intellectual and social orientation. The committee members believe that even under the present program using the Sophomore Orientation Committee, many freshmen do not come to understand what is expected of them and consequently suffer throughout many of their first-term courses. They also feel that dormitory living as it now stands provides freshmen only its schoolboy limitations for raising cain and does not give them the opportunities for a full social education which living in a group can offer. Many freshmen, the members think, are not really exposed to the fact that they are social beings until they join fraternities in their sophomore year.

So the committee is in the process of recommending several changes. The first, arrived at by working with Mike Miller '59, head of Freshman Orientation, and David Blake '61, Chairman of the Sophomore Orientation Committee, is the elimination of that latter committee, in spite of its good record so far. If this recommendation is passed by the Undergraduate Council, the Academic Committee will consider several proposed improvements to replace the Sophomore Orientation Committee. Instead of the inter-class strife fostered by the present system - glorious, perhaps, but not educational - they have suggested that orientation toward Dartmouth's intellectual atmosphere be the responsibility of a carefully chosen group of seniors. These men would work individually with the faculty advisers of the freshmen, and the extent of their function would be left entirely to the discretion of each professor. Advisory meetings held in the faculty members' homes and offices could then be scheduled during freshman week, instead of being put off until the weeks following, which has been the method in the past.

The committee's second recommendation is less individualized, more a matter of procedure; in short, replacing the Sophomore Orientation Committee with a different kind of student organization built around each dormitory. This suggested organization would include the seniors working with the faculty advisers. And in each dormitory the social activities such as rallies would be taken over by the Interdormitory Council; all three upper classes would be on each dormitory committee and would always be present to help the freshmen right in the place where they lived. The Academic Committee believes this program would result in improved responsibility and discipline in the dormitories, especially since the proposed organization would be a continuing body, not one re-chosen annually. And because it would have some kind of continuing existence, it might also become a channel up which student leaders would rise.

Though still only ideas, both such a dormitory organization and the plan for senior advisers would take advantage of a persistent reality at the College, the dormitory bull-session. Men may cut classes and profess all kinds of apathy toward books and learning, but there are very few who do not seek friends and understanding, and some place to voice their own ideas. Here, quite possibly, is the opportunity to inculcate whatever one Dartmouth man can in another, especially concerning what one owes Dartmouth, and what the College owes each student as well.

FOR a long time now many members of the College, students and faculty alike, have felt the need for freer and more lively talk, and certainly dormitory sessions won't serve everybody's purposes.

Many of the seniors were greatly impressed by their most controversial speaker in the Great Issues course during the fall term, William F. Buckley, editor of the National Review. In contrast to most of the other speakers, his personal beliefs seemed incorrect to many of his questioners, and the arguments ensuing were the most spirited, intelligently informed, and probably the most educational of the whole term.

This highly rewarding experience made several men reflect that a series of public debates between a speaker or speakers and the undergraduate body, as opposed to just a Forensic Union or a lecture series, might do more to advance the intellectual spirit of the College than any other single activity. They claim that a certain magical ferment gets started inside a student when he commits himself to saying what he believes and why he believes it in front of a large, sympathetic, but also critical audience of his contemporaries.

Had a debate such as Mr. Buckley inspired been conducted on Dartmouth spirit or on the individual's responsibility, more students might have been prompted to act intelligently during the riot.

If this notion has any merit at all, it might be worth the Tucker Foundation's consideration. As one of the College's endowed operations, avowedly concerned with the moral well-being of the undergraduates, the Foundation could foster the free interchange of ideas and the necessity every student faces for logical, honest thought about his actions in relation to others by simply doing the following: First, it could bring in an authority to speak on current events or, in fact, any of those old issues which are always burning for undergraduates - sex, money, politics, religion, heredity and environment, the College for or against the individual, responsibility, spirit, if you like - the list is endless. The speaker would only talk for, say, twenty minutes in defense of his particular point, and then five minutes apiece could be allotted to two undergraduates selected to present the opposite view. After something like a two-minute rebuttal from the speaker, the discussion could be thrown open to defense and attack from the floor. There are many men on the faculty, notably in the humanities, whose ability to direct class discussions is much admired, and they might be asked to serve as moderators, or more as inciters to what might be termed educational polemics.

Today we bemoan the lost art of conversation, and intelligent argument seems equally obscured. However, such debates would be fairly inexpensive and easy to organize for the Tucker Foundation. And in contrast to academic performance, sports, other extracurricular events, or "goofing off' in the dormitories, they could easily turn into one of the most positive means of letting undergraduates come to their own realization of what they are and can become at Dartmouth.

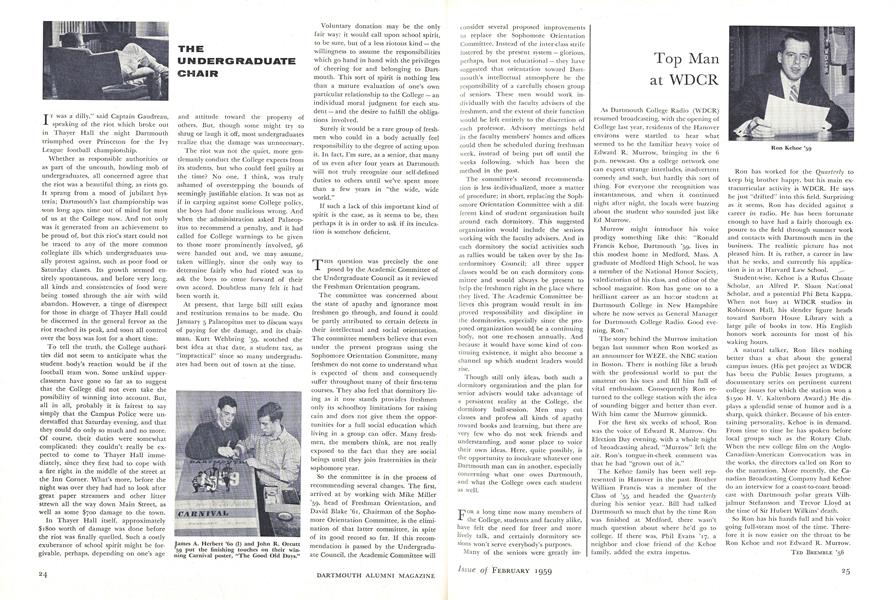

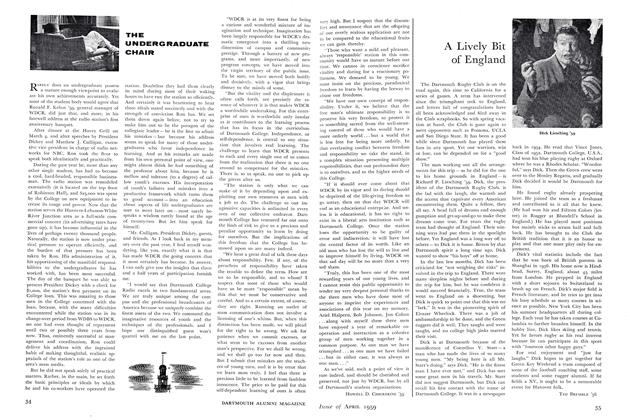

James A. Herbert '60 (l) and John R. Orcutt '59 put the finishing touches on their winning Carnival poster, "The Good Old Days."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

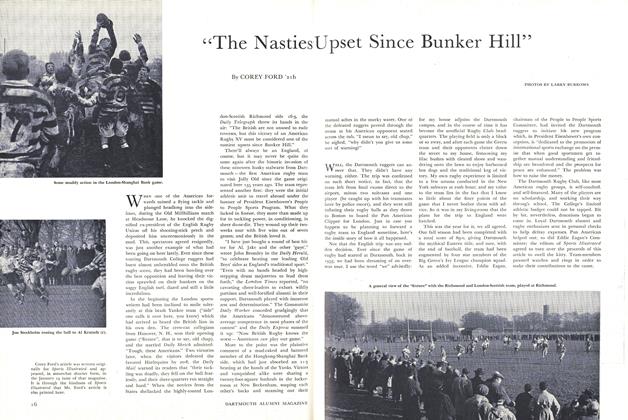

Feature"The Nasties Upset Since Bunker Hill"

February 1959 By COREY FORD '21h -

Feature

FeatureThat Other Dartmouth Carnival

February 1959 By FREDERICK L. BACON '59 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

February 1959 -

Feature

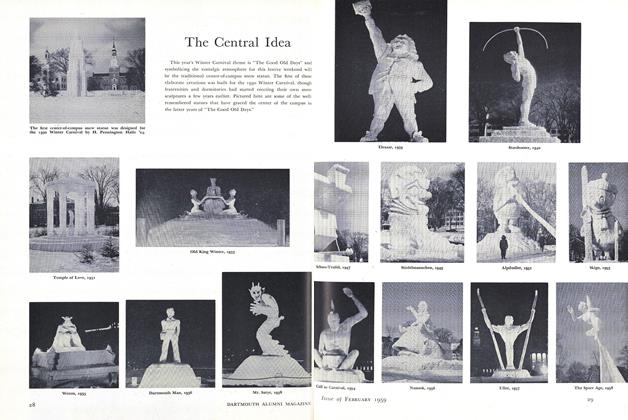

FeatureThe Central Idea

February 1959 -

Article

ArticleSome Consequences of Inflation Psychology

February 1959 By COLIN D. CAMPBELL, -

Article

ArticleShould We Blame the Unions?

February 1959 By MARTIN SEGAL

HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1958 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59