How, exactly, can "independence in learning" be fostered best at Dartmouth?

This question matters a great deal to a great many men engaged in running the College, so much so, perhaps, that they feel that the question is their province alone. But it means much to an important segment of the undergraduate body as well, those who think for themselves. These students, upon whom the question not only is based but also redounds, recognize that they will owe at least something in their cast of mind to Dartmouth, if not, oftentimes, much of their ability to think at all. Many of them hearken to President Dickey's much-quoted remark: "We are the stuff of an institution and what we are it will be."

Independence as a primary principle in learning would definitely seem to imply the belief that the best, and perhaps the only, kind of permanent and worthwhile education is self-education. However, some thinking students, honest with themselves, believe the self a boy at Dartmouth calls his own is built more by the molding forces of the men who teach him than by his own impetus.

Disregarding the ambiguous implications such a belief has for one's concept of individuality, we all will give their notion of non-independence some credence, certainly, for what Dartmouth man recalls not ever having benefited from knowing one professor or more well? And as we do, we can't avoid a question their stand raises relative to the one above; namely, how can a boy's sense of what he means and of what the life around him means, and especially of sense of the life and meaning he finds in books - in short, his educational self —be best built first, so that he may proceed to learn, for himself, independently?

These undergraduates would say that, above all, the educational self should be built, perhaps can be built only, by professional stimulus in small classroom situations where the professor's personal qualities so enliven his material that a student can't hear his talk about Hanover winters without learning more about the course material.

And so these students, in so far as they comprise a group, would look somewhat questioningly upon the recent $500,000 grant for establishment of the Albert Bradley Center of Mathematics and Mathematical Research by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. They might take umbrage at the College administration's statement as reported in The Dartmouth: "It was in recognition of the fine work being done by Kemeny and his associates in the College Mathematics Department that the Sloan Foundation granted the money. President Dickey stated that these men had established an undergraduate mathematics program that has gained national recognition."

Not intending to impugn Professor Kemeny, chairman of the Mathematics Department, nor that department's present needs, nor its deserving the grant in the least, they might ask if, as a matter of policy, rewarding personal and scholarly achievement with improved plant facilities was not incommensurate with the College's over-all policy of independence in learning, especially since that over-all policy, as they have reasoned, puts primary stress on the personal classroom activity of each professor.

In fact, some of them have suggested that it would have done much more to further the College's stated aims had the grant "in recognition of the fine work being done" brought someone like Robert Oppenheimer to Dartmouth instead of the tentatively forthcoming construction at the corner of Elm and North Main Streets; and they would have a point, theoretically.

Strangely enough, their theoretical point would be more strongly made against a more practical and prosaic matter, the Hopkins Center, than it would be against the theoretical science of mathematics. Warner Bentley, head of COSO, for drama, and Professor James Sykes, for music, have long hoped to see better and more practical facilities, and now they will have facilities galore, once the Hopkins Center is built. But then, these undergraduates argue, they will have even better cause to moan than, say, The Players now have with the tiny Little Theater in Robinson Hall, for the Hopkins Center will be ridiculously undermanned. Not only, if the departments' memberships do not significantly increase, will there be an inadequate number of professors to provide the personal controls necessary to the practice of these arts, but also there are no signs evident to these students that Dartmouth is attracting, or is trying to attract, applicants who will, in a body, take full advantage of the elaborate and highly expensive Hopkins Center.

It seems overwhelmingly true to these undergraduates that merely the physical shells of learning can in no way substitute for the necessary increase in the professorial staff to give Dartmouth the essential guts of an educational process through independence - highly competent men, both as teachers and as people. After all, Plato and his students had only a pleasant grove in which to stroll, the lively thought which comes from friendship's talk, and the art of listening well. No one, of course, would ask that all professors be Platos, even though many at Dartmouth possess the last two qualities enumerated. However, this particular group of students feels that the principle which first led it to think for itself should be promulgated above and beyond all others in this, "a community of learning." And perhaps they are right.

Dean Joseph L. McDonald, who retires this year, receives from Edward W. Gude '59, former president of The Dartmouth, an engraved silver cigarette box "in appreciation for valued counsel and true friendship to The Dartmouth and to the undergraduates of the College. The Dean was guest of honor at the paper's annual dinner last month.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

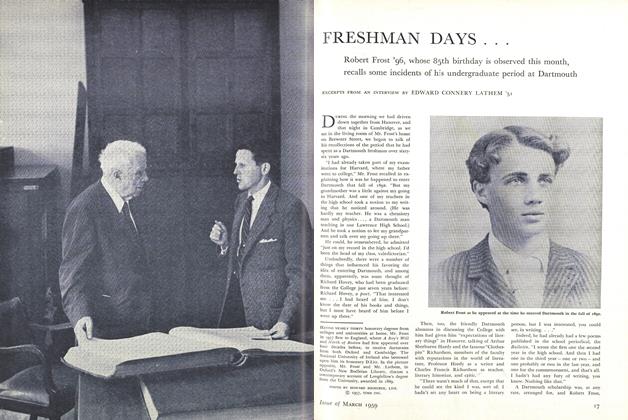

FeatureFRESHMAN DAYS...

March 1959 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature"Spoiled Children" of Hanover: A Letter from Charles Doe, 1849

March 1959 By JOHN P. REID -

Feature

FeatureSCHOOLMARMS, GRAMMARIANS and ANARCHISTS

March 1959 By ROBERT S. BURGER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1959 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1959 By ROBERT L. MAY, EDWARD J. HANLON, BRUCE W. EAKEN

HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1958 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

FEBRUARY 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59