EVER since the Saturday Evening Post printed an article an Football Coach Bob Blackman, many people in the College have wondered whether to praise or condemn his methods.

The article ("Ivy League Revolutionary" by Murray Olderman, November 8, 1958) presented three controversial aspects of Dartmouth football in what might be called a partially unfavorable light. It suggested that the coach pushes Ivy League protocol to the limit in recruiting his players:

Tactical gimmicks aren't enough to make a winning college team these days. The coach must also keep the playing talent coming in. Blackman has assiduously cultivated the help and support of football-minded alumni. He is always available to address gatherings of alumni, and he has a magnetic effect on them. Round-cheeked and wide-eyed, he turns on a captivating grin and exudes sincerity.... Throughout the winter, spring and summer Blackman a campaign to steer as many such boys as possible to Hanover. Although Dartmouth can't offer them straight athletic scholarships, it is possible for a boy with high enough grades to qualify for aid that will see him through an Ivy School.

Further, the article seemed to present Coach Blackmail's commendable desire to win and its natural outcome, his strict discipline, as though he were ferociously meticulous to the point of sadism:

Blackman maps out practice sessions down the fraction of a minute. He is just as exacting with his squad off the field. The one time the Dartmouth boys have seen him blow his top was the night before the Columbia game in New York last fall, when two players strolled into the hotel lobby nonchalantly lapping ice-cream cones.

"Was he mad!" recalls Joe Palermo, the 1957 team captain. "He let 'em have it right there. You know, when you're in training at Dartmouth you're supposed to eat only what they give you."

And lastly, it implied that the Ivy League spring practice ban is a thorn in the coach's side which spurs him to drive his team even harder:

Eastern observers have been amazed by the multiplicity of offenses and defenses he has installed at Dartmouth despite the handicap of no spring practice.

"Maybe they don't have spring practice," said Fritz Barzilauskas - who may or may not have been kidding - after scouting a Dartmouth game for Yale, "but they must play an awful lot of touch football up there. Or else he's got 'em out secretly at three o'clock in the morning."

Thus through the Post's limited viewpoint, perhaps over-simplified for readers unfamiliar with Dartmouth or with collegiate football, national attention has been focused on Coach Blackman's methods, his ways and means to several ends. But before judging those methods rashly, we'd all do well to consider their ends while keeping in mind the kind of institution Dartmouth is becoming.

THE administration and faculty are determined that a student spending four years at Dartmouth shall receive an education of higher academic caliber than he now does, and what is more, that it should be an education which is a whole life-process, not merely an award for excellence in scholastic regurgitation. Operating on the premise (which I believe is altogether correct) that the undergraduate rarely knows what is good for him, or what is good in him, they aim to build up his abilities as a human being and his confidence in himself through those abilities. To achieve these ends more fully they have already instituted the new three-course, three-term system, not to mention the independent reading program, have planned the Hopkins Center, and have made the Tucker Foundation operative.

The goal is not a new concept to anyone familiar with Dartmouth's history; the College has continually tried to help its men grow (in what always has been essentially their own self-education) toward becoming individuals aware of their own powers and responsible for the best use of them. However, such an education naturally has to change its methods as the times and personnel change. And so the ideas of the men in authority have shifted to take the coming crop of "war babies" into account. Looking ahead, they are planning now to raise the standards of the curriculum, to make Dartmouth's admissions more selective, and to gather as many brilliant young professors in each department as possible. These measures are in large part the realized dreams of many faculty members. They feel that the higher academic standards of the three-term system will tend to bring them the kind of exceptional students who will be humanly and professionally interested in their particular fields.

In contrast to the faculty's elated anticipation of such whole-minded scholars for students, some of the older men in the College fear a certain one-sidedness in the increased emphasis on intellectual abilities. One has even asserted that in ten years Dartmouth, ruled more by students' and professors' desires for specialized academic excellence, will be "different but not better." These older men feel that an undergraduate's education proceeds best through his human and humane exposure to a variety of experiences. They rank extracurricular activities very high for their value in giving a student a fuller awareness of life's multifarious demands upon him and the variety of possible responses he can make to them.

These older men believe that there will be a cutting down on fruitful extracurricular activities by most students in order to meet the heavier demands of an education by specialization. And most of them would go so far as to say that education by specialization of skills is no education at all.

There is no real disagreement between this portion of the administration and the faculty as to the end of education; rather, they simply see their respective means to that end mutually exclusive to some degree. It may well be that we shall never know whether there is any significant degree of exclusion, since a third group of younger officers, who will probably play the major role in determining the College's future policies, seem not at all involved in this divergence over which methods are to be emphasized. Instead, they seem to rely on facts already proven.

That is, they point to the top students in any given area of endeavor and then point out that the best students usually have a variety of abilities and are near the top in several areas. They further note that the more nearly a student works to his full capacity in more areas, the higher his performance is in each given area. Here it should be firmly stated that this pattern of behavior is as true in football as in any other extracurricular activity. These men are inclined to explain this paradox through the student's budgeting his time, his efficient and thorough use of his concentrative energies, and an inner discipline coming from his confidence in himself. And they predict this state of high self-confidence linked to many excellent human abilities for a substantially larger percentage of the student body in years to come.

SO it's logical to assume that the new goal for "a Dartmouth education" will be the one to which Coach Blackman will align his football policies. But it would be unfair not to say he's done so already. More than any other Ivy League coach in recent years, he's called forth efforts from his teams which they themselves did not know they coud make, and which they doubtlessly would not have made had not he been here. His discipline trains his boys in a kind of quick-decision thinking and in the confidence to abide by and carry out their decisions. What better qualities could one ask for in the social education of a person? And why should he be made a controversial figure when his method gets better results and his players better fulfill their potential as athletes by adhering to it? Were the Ivy League to permit spring practice, their performances would become even better, and the coach has often said as much.

Our present athletic situation seems to me to be a question of the College's organizational system lagging a little behind the needs and abilities of its personnel. But fortunately the personnel, such as Coach Blackmail, have their ultimate goals in view while at the same time seeking out new methods which they themselves are able to put into practice. As such, the coach would appear to be, if not a true Dartmouth man, almost an institution unto himself, and more beneficial to his boys for being so. We should praise his disciplinary method and his hope for spring practice since they help to advance the new idea of a Dartmouth education.

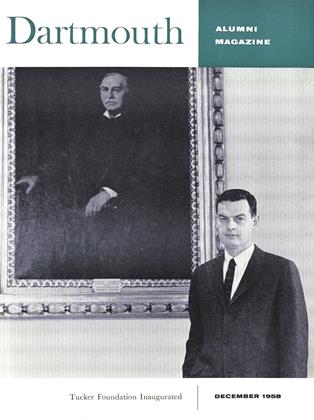

Howell D. Chickering '59, this month's occupant of "The Undergraduate Chair," comes from Wilmington, Del. An English honors student, he won the Lockwood Prize last year. He is the son of Howell D. Chickering '34.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureConvocation Installs Tucker Foundation

December 1958 -

Feature

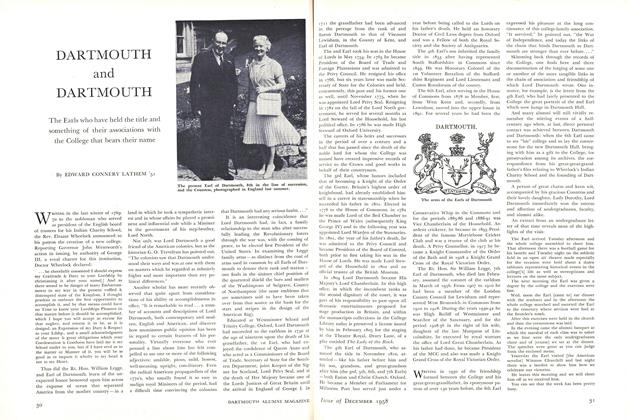

FeatureDARTMOUTH and DARTMOUTH

December 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

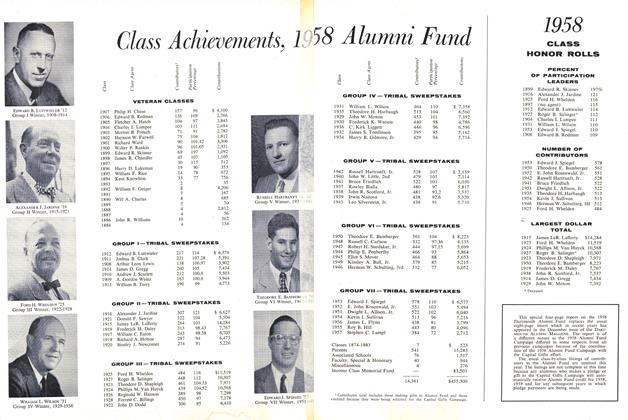

FeatureClass Achievements, 19

December 1958 -

Feature

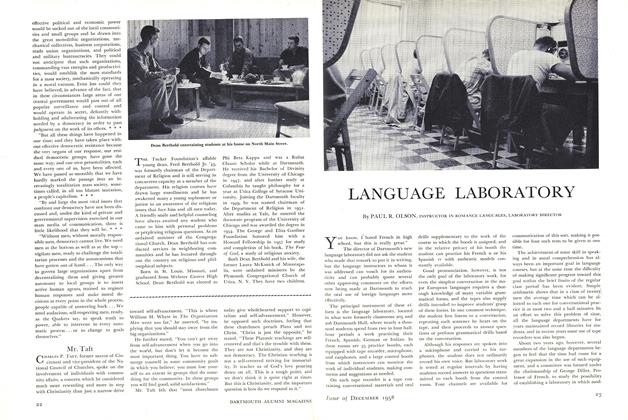

FeatureLANGUAGE LABORATORY

December 1958 By PAUL R. OLSON, INSTRUCTOR -

Feature

Feature1958 ALUMNI FUND REPORT

December 1958 By William G. Morton '28, -

Feature

FeatureALUMNI FUND PLANS FOR 1959

December 1958 By Donald F. Sawyer '21,

HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

FEBRUARY 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59