DEAR MR. EDITOR:

I write this letter for two reasons. One, as a Brown man smarting from two successive football defeats inflicted on a good Brown team by a better Dartmouth team, I am determined to carry out my New Year's resolution and be kind to any Dartmouth alumni in the Gaza Strip. And two, having read Bate Ewart's DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE for October 1958, I am moved by Professor Richard McCornack's excellent article, "Unrest in South America," to comment on his appeal. "It is up to us," he writes, "as individuals and collectively as a nation to do all in our power to eliminate friction between ourselves and the republics to the South." I would like to describe what one Dartmouth man, Bate Ewart '42, is doing in a difficult and delicate situation to help eliminate some of the frictions between the United States and the Middle East.

In this 20 x 5 mile strip there are 225,000 bona fide Arab refugees driven out of Palestine by the war of 1948 and 50,000 economic refugees in Gaza (created by the flood of Palestinians which has ruined their livelihood). As the UNRWA Field Administrative and General Services Officer in charge of personnel and employment, Bate Ewart has, as one of his several responsibilities, the task of dealing with 30,000 applicants for 3,000 jobs. Inasmuch as the individual applicant has few inhibitions and no selfimposed restraints, Ewart's office is a constant storm center of emotional outbursts. For example, recently, a young student walked into his office and demanded a job. He was informed that the position was filled. In his resentment he smashed two typewriters before he could be invited to leave. When Bate Ewart returns home after work he finds perhaps a physically handicapped job hunter or even a would-be suicide waiting for him, who will beg, pray, threaten, or curse his father in order to emphasize his desperate need of a job.

One applicant, who will remain anonymous, addressed the following appeal to Bate:

"Dear Mr. Ewart: I myself accept, defend and support Aznhower (Eisenhower) Principal. Dear Mr. Ewart: If I were a deligate to the united Nations, I would declare to the world my support for Azenhower principal.

Dear Mr. Ewart: I hate all which attack the principal.

Dear Mr. Ewart: But for regret, I am poor and I request you to employ me to continue my efforts in supporting Azenhower principal.

Dear Mr. Ewart: I send my love to you and Azenhower and dullas (Dulles) and I hope you are well.

Dear Mr. Ewart: I want from you the answer."

The answer was "NO."

Ewart's hearty laugh, amazing patience, natural sympathy and respect for the dignity of the individual refugee compels their respect for him. He is never callous, nor is his voice strident. Whenever the applicant becomes unmannerly, unrestrained or even goes to the extreme of threatening suicide he is very firm but not tough.

Judged by the ordinary criteria of life, this is a thankless job. Regardless of how many refugees he aids, the line is never-ending, and seems to stretch to infinity. He takes the long view, has a deep abiding faith in God and his fellow refugee workers. Fortunately he has a wife who is a good linguist, and a most gracious hostess. One day the Ewarts may give a dinner for Mr. Arnold Toynbee — on a visit to Gaza. The next gathering may be a cocktail party for some forty or fifty international personnel of UNRWA and UNEF, and subsequently there will be a buffet dinner for the Arab refugee employees, and ALL will feel perfectly welcome and at home.

The bitterness which many of these refugees entertain toward "Imperialist" America for having helped create Israel in their homeland of Palestine is changed to wonder and appreciation by contact with a man like Bate Ewart. When a frustrated refugee with hate and resentment oozing from every pore walks into Bate's office, and is met with a smile and a courteous greeting, he recognizes that there is a difference in what American foreign policy has done to him, and what this individual American tries to do for him.

When Wendell Willkie wrote his little book One World in the early forties, he devoted a section to the great reservoir of good will which he found toward the United States. In the main, this was due, he found, to the missionary or the teacher, doctor, nurse or agriculturist. Even the most casual reader of the newspaper today knows that this good will has been largely dissipated. One of the principal reasons is that a reservoir of good will runs dry whether in South America or the Middle East unless it is constantly being replenished with men of imagination, dedication, and those "who work with heart," as a Beirut banker put it in discussing refugee work with me.

A school teacher describing Bate Ewart recently said, "When the Jews invaded Gaza in 1956, it was Mr. Ewart who sympathized with the people here, but not all Internationals did." His sympathy encouraged those who needed help in those days of trouble.

Recently, an Arab refugee, a former laborer with me in 1949 and '50, and I were having a cup of coffee. When Bate Ewart came by he stopped and chatted with him in Arabic. As he walked away, the refugee made a gesture of appreciation toward him and said in broken English, "The Arabs here know Mr. Ewart is a good man."

One could say of him, as it has been said of others, "that through his faith and steadfastness, the sufferings have been eased, good will created and justice established" among the refugees with whom he has worked, limited as he has been by political and economic conditions over which he has no control.

My work in Gaza has been made easier and more significant as the result of knowing Bate Ewart, Dartmouth '42, and I wanted some one at Dartmouth to know about him and his contribution toward removing the frictions which exist between the peoples of this part of the world and the United States of America.

Near East Christian Council CommitteeGaza, Palestine

P.S. You may be interested in an experiment which I carried out recently. I have often wondered whether Dartmouth men are just born that way or acquire their loyalty over the years.

Recently while friend Ewart and his wife were away on a weekend trip, I tried an experiment. Finding purely by accident among my possessions a Brown University shirt just the right size for a 2-year-and-4-month-old boy, I offered it to John Ewart who promptly refused it. Then I tried to put it on him but he struggled so that I found it impossible to do it alone. I called the gardener and night guard, and sweated it on him. That night, after a visit from an indignant parent, following his return from his vacation, I was convinced that Dartmouth men are born that way.

My heart smote me and I had the NECCRW Knitting Center make up a Dartmouth green sweater with a white D which I presented in due time. The old man was pleased and the small boy slipped into the sweater with a grin on his face.

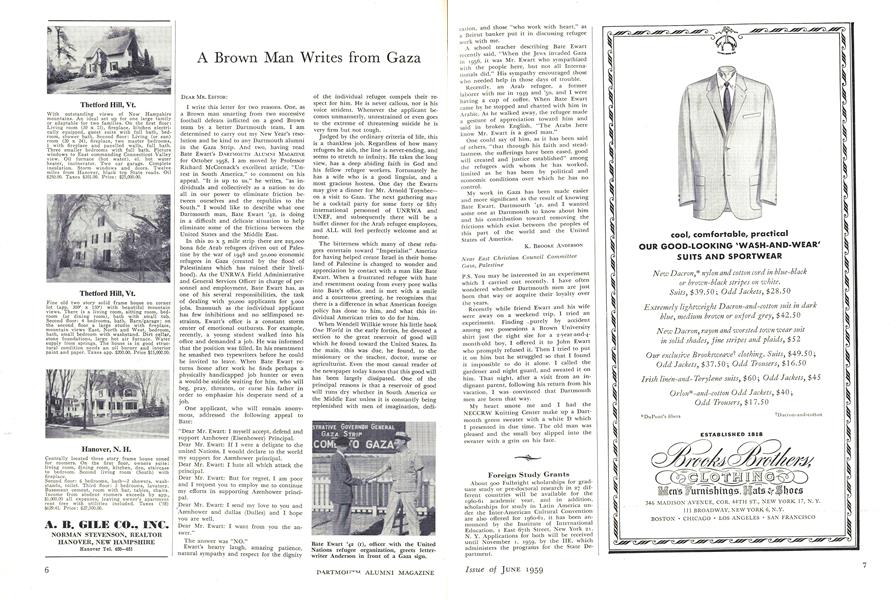

Bate Ewart '42 (r), officer with the United Nations refugee organization, greets letterwriter Anderson in front of a Gaza sign.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMy 65 Years as a Class Secretary

June 1959 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

FeatureA Panathenaic Prize Amphora

June 1959 By DIETRICH VON BOTHMER -

Feature

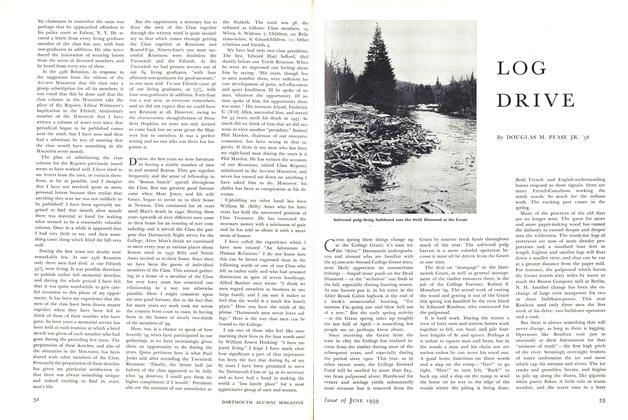

FeatureLOG DRIVE

June 1959 By DOUGLAS M. PEASE JR. '58 -

Feature

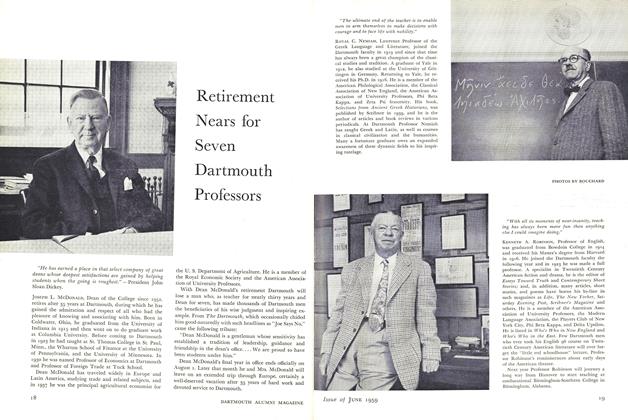

FeatureRetirement Nears for Seven Dartmouth Professors

June 1959 -

Article

ArticleThe Fraternity Discrimination Issue

June 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1959 By RONALD F. KEHOE '59

K. BROOKE ANDERSON

Article

-

Article

ArticlePresident Busy

January 1938 -

Article

Article"Man of the Year"

May 1950 -

Article

ArticleRenovations on Campus

Nov/Dec 2010 -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE BUREAU OF PERSONNEL RESEARCH

MARCH, 1927 By Harry R. Wellman -

Article

ArticleDecember, 1920

December 1940 By L. K. N. -

Article

ArticleThayer School

June 1957 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29