IN an interview over Dartmouth's radio station WDCR, on the night of April 13, President Dickey discussed the past history and present status of the official College policy, voted by the Trustees, that all Dartmouth fraternities must eliminate from their charters by April 1, 1960, any clause barring fraternity membership to a man on grounds of race, color or religion. Following, as tape recorded, are the questions asked by Allan W. Cameron '60, station manager, and the replies made by President Dickey:

Mr. Cameron: We'd like to start this evening's discussion with the history of the discrimination issue at Dartmouth, starting right after World War II, and perhaps you can fill us in on this.

President Dickey: I'll be glad to try. As I did on the previous occasions when I accepted your invitation to speak to the College community, I think I should make clear that I am speaking entirely extemporaneously, and that I'll be taking your questions as they come without having had an opportunity to study them previously. Accordingly, while I shall be glad to stand by the essence of what I say, I hope I may be forgiven if I don't get things just precisely the way I would put them if I were working from a manuscript.

This whole subject of the policy of the College toward eligibility for membership in Dartmouth fraternities, so far as I'm concerned, goes back to the very first days that I was on this job, the fall of 1945. At that time there was considerable interest throughout the country in this issue, and it was expressed to me by Dartmouth faculty members, by members of the alumni body, and by members of the student body. There were two schools of thought: (1) that it was high time for the colleges through their official bodies, the boards of trustees, to step forward and take an authoritative, definitive position against the bars to membership in a college fraternity on grounds of race, color, or religion; (2) the other approach was broadly that of working it out over a period of years and permitting the action to grow out of a general consensus. Dartmouth chose, as you know, the second course. That consensus finally was reflected in the Undergraduate Referendum of 1954 and the recommendation from the undergraduate body to the Trustees at that time.

Mr. Cameron: Well how did student initiation of this movement come about?

President Dickey: I think it's fair to say that the original, formal expression of student interest in the subject came to the fore in the fall of 1949. There had been sporadic expressions of interest prior to that time, but in the fall of 1949 the Northeastern Interfraternity Conference adopted a recommendation addressed to the National Fraternity Conference. The recommendation called for the elimination of these so-called discriminatory clauses by all national fraternities. That recommendation was not accepted, as I recall, by the national fraternities, but it did serve to alert the Dartmouth campus to the importance of this issue, and at a meeting of the Dartmouth Interfraternity Council (my notes here show this was held on October 26, 1949, a few weeks after the action of the Northeastern Conference) the Council unanimously endorsed the position of the Northeastern Conference, calling for the elimination of these clauses. That was back in 1949, ten years ago.

Now I think it is fair, and quite important, to say one thing here. While the Board of Trustees at Dartmouth decided in 1946 not to take any authoritative action at that time requiring that these discriminatory clauses be eliminated, I decided that, in fairness to the College community, the fellow on my job should make his own personal position clear. As early as 1948 I stated, in writing, my view to be as follows: that this College neither teaches nor practices religious or racial prejudice, and that I do not believe it can for long permit certain national fraternities through their charter provisions or national policies to impose prejudice on Dartmouth men. That was the statement I made, in 1948, of my personal position, and that has continued to be essentially the way I feel about the matter.

Mr. Cameron: There were three referendums taken among the student body on this issue after the original initiation in 1949. Could you go over those three referendums; what they asked, and what the results were?

President Dickey: Yes, and I think the fact that there were three different polls, so to speak, taken on this subject over the period from 1949 to 1954 is about as concrete evidence as can be offered that this was not a casually taken decision in 1954. The first poll that I have any knowledge of was taken in the late fall of 1949 — I think it was November 1949, following this Northeastern Conference recommendation and the action by the Dartmouth Interfraternity Council. At that time TheDartmouth, and your predecessors, WDBS, the Dartmouth Christian Union, the Dartmouth Human Rights Society, and the National Student Association Council sponsored a campus poll to determine undergraduate sentiment on this issue. They polled 2,359 men, a very large proportion of the student body. Of those polled, 1,754 favored eliminating the clauses, 375 favored maintaining the clauses, and 230 were undecided. That was the first poll, and it was a very broad registration of sentiment, not precisely defined in terms of actions to be taken. It covered 80% of the undergraduates at Dartmouth. 74% plus favored the elimination of the clauses and actually 72% of fraternity men on the campus favored the elimination of the clauses at that time. I think it is very important to say that this has not been an issue between fraternity and non-fraternity men, and I feel that every Dartmouth man can be very proud of that fact.

Now you ask me about the three polls. The second poll was a more formal referendum authorized and conducted under the auspices of the Dartmouth Undergraduate Council, and this was taken in the form of a referendum of the student body in March 1950. This followed a really very heated and extensive debate of the issue on the campus. That referendum in March 1950 was on specific proposals for action as distinguished from simply registering a broad sentiment on the question. Proposal number one, in 1950, called for the enforcement of the elimination of these clauses within two years. Proposal number two required that each fraternity should make efforts to get these clauses eliminated and if they were not making satisfactory efforts, then that fraternity would be barred from the campus. Proposal number three was in favor of no action being taken on the clauses.

The first proposal requiring enforcement within two years received 885 votes, the second proposal requiring efforts by each fraternity toward that end received 1,354 votes, and the no-action alternative received 248 votes. Here again you had a very heavy vote by the student body, and if you take proposals one and two, both looking toward' the elimination of these clauses, you have a very heavy majority in favor of their elimination, with the formal majority favoring action by individual houses without enforcement of a general ban. Now this was what set up the situation for the referendum on which we are operating today, the referendum of 1954.

The 1954 referendum was again conducted under the auspices of the Undergraduate Council. It was conducted in March 1954, and I think it would be worthwhile to say a word concerning what took place between the 1950 referendum and the 1954 referendum. During that period the Undergraduate Council established a committee to review the actions being taken by the fraternities to carry out proposal number two of the 1950 referendum; that is, action looking toward the elimination of these clauses through voluntary persistent, systematic effort on the part of the fraternities. During this period one fraternity, as I recall, went local over the issue. They were subjected to criticism by the Undergraduate Council for insufficient action; they decided that on their own they wanted to get the matter cleaned up and they went local. But it became clear, or at least the leaders of the undergraduate body felt that it was clear by 1954, that this system had pretty well exhausted its ability to get results.

So, they held another referendum in March of 1954 and this third one again had three propositions. The first proposition was that by April 1, 1960 — that is, six years from the time of the referendum - authoritative action should be taken by the Trustees of the College requiring the elimination of these clauses. The second proposition was more or less for the continuation of the existing voluntary efforts which had been instituted under the 1950 referendum. The third proposition, as it had been in both previous referendums, was to do nothing about the matter. Well here you got a vote of 1,128 men favoring proposition number one, namely the April 1, 1960 deadline. And it was expressly stated on the ballot at the time that if this policy was adopted, the Board of Trustees of Dartmouth College shall be requested by the Undergraduate Council to make it binding on April 1, 1960, and that a majority of all the students who voted in that referendum would have to favor item one before that action would be taken. Item two, the voluntary action proposition received 848 votes, and item three, or doing nothing, received 272 votes. It's interesting to me as I look back that on all three polls about 10%, actually something a little less than 10% of the student body, favored doing nothing, but that on all three polls the sentiment was overwhelmingly in support of the elimination of these discriminatory clauses and that the only difference of opinion was when and how.

Mr. Cameron: Now after this referendum which definitely endorsed by a majority the proposal number one for the April 1960 deadline, what action did the Trustees take?

President Dickey: On April 16, 1954, David McLaughlin, president of the Undergraduate Council, addressed a communication to the Trustees of Dartmouth College from the undergraduate body. He referred to the referendum and stated that with 86.5% of the student body voting - that is, 2,248 students voting out of the entire student body - a required majority of 1,128 had backed proposal one and that therefore on behalf of the student body they were requesting the Board of Trustees to take official action to bar as of April 1, 1960 - six years from that time any fraternity which still had a written or unwritten clause that made men ineligible for membership solely on the basis of race, color, or religious belief. The Trustees received that communication and after discussion in the Board they accepted the recommendation and at their meeting on April 23, 1954 adopted the policy in the very words adopted by the undergraduate body in the earlier referendum.

Mr. Cameron: We now get into the real meat of this evening's program, the things that affect us immediately within the next year and in some instances within the next week. What is our status today? In other words, could you give us a brief outline of how many fraternities have taken action to get rid of their clauses and how many still have them?

President Dickey: I think this is a matter where information is still not as precise as I should like to have it. The picture that I have is that there are, at the moment, about six houses — put it this way, five to seven houses - that still have explicit national clauses or policies that make it impossible for those houses to comply with the College policy. I think the other houses by and large are in the clear, although there is some talk about some of those houses having national policies, as distinguished from national clauses, which are at variance with College policy. I simply do not know about that, but the picture which I am given by undergraduate leaders and by the Dean's Office is just about that.

Mr. Cameron: One of the big items of concern in the undergraduate body has been the possibility of postponement of the 1960 deadline, as requested by one house. What is the Trustees' position on this?

President Dickey: I'm very glad you asked about the Trustees' position because that is the only relevant question: What is the Trustees' position? This has now passed out of the area of administrative discretion and is a matter of College policy fixed by the Board of Trustees, the ultimately responsible authority in the College. I cannot speak for the Board other than to tell you what they've done and what they have discussed so far as this question is concerned. The Trustees have had occasion within the past year to have this very question raised as to what their attitude would be on any suggestion of postponement. At the time the question was raised with them they were unanimously and emphatically clear that it would be not in the interest of Dartmouth College to have any question of a postponement raised or considered; that six years after the action of the undergraduate body in 1954 was indeed a very long time to wait for action; and that further postponement would simply not be in the best interests of Dartmouth College on this question.

Mr. Cameron: Perhaps we could move on to 1960 in our chronological study. What action can be taken against houses which might not take the necessary action by the deadline, which might just sit back and hope that it all blows over and nothing will happen? Perhaps first we might ask what is the out for houses with clauses they can't get the nationals to revoke?

President Dickey: Well, I'm not sure, and I'm not very much inclined to offer gratuitous advice to people in a matter of this sort. But I do want to make one thing very clear: that I am willing myself, I know that my colleagues in the administrative offices are willing, and I'm sure that the Board of Trustees are anxious to be just as helpful as they can to every Dartmouth fraternity group, to preserve this quality of Dartmouth's social life, because we believe that fraternities have a place in the healthy social life of the College. Now just what that help can be will depend upon the individual circumstances of individual houses. I have been asked by one or two houses what my personal advice to them would be, and in both instances I've suggested to them this course of action. I have said that if you find yourself in 1960 with your national still not in compliance with College policy, I think you might well consider taking the initiative and saying to that national that it is not in compliance with the basic policies of Dartmouth College as laid down by the Board of Trustees in 1954 and that therefore the Dartmouth chapter is requesting a voluntary suspension - I repeat, a voluntary suspension of its national affiliation until the national fraternity is in compliance with Dartmouth policies. My guess is that such an action would do more than any other thing I can suggest to bring home to the nationals that if they really want chapters such as the Dartmouth chapters in their national fraternities it's up to them to take action.

Mr. Cameron: Now, to get into the question I hinted at earlier, what can the College or the Trustees do to a house which refuses to take any action at all and retains a discriminatory clause in its constitution?

President Dickey: Well, let's start with what the resolution transmitted by the Undergraduate Council to the Board of Trustees said in 1954. The referendum stated that any such fraternity shall be barred from all interfraternity participation, and the communication directed to the Trustees of the College from the Undergraduate Council at that time stated that interfraternity participation in this instance is meant to include all activities which embrace interfraternity competition, including fraternity rushing and participation in all other fraternity projects. In short, it seems to me that there is simply no question but that any such house would be denied status as an officially recognized fraternity on the Dartmouth campus.

Mr. Cameron: Now, suppose you have the case of what we may call an outlaw house, a house which says all right, we won't participate in official rushing, we won't participate in interfraternity activities; we are just going to sit here and keep our own distinct social group as a national fraternity made up of members of the Dartmouth undergraduate body, but not recognized by the College.

President Dickey: Well I don't think I can attempt to imagine what that kind of an outlaw would look like or what he would do in relation to Dartmouth College. I don't think Dartmouth College is out looking for trouble, but it is inconceivable to me that any respectable national fraternity would permit a group to represent it in that way on the campus. I would suppose that the first thing that would happen would be that the national fraternity would say we can't afford outlaws, gentlemen, thank you very much. However, assuming that that isn't so, let me assure you that Dartmouth College cannot afford outlaws in any form. Men are here to enjoy the privilege of higher education, and if they cannot enjoy it within the basic framework of Dartmouth's laws, I'm afraid the answer is all too clear. But I don't expect that. I don't expect that at all. I really think that it's very important to say that this is not a matter of gadgets or of penalizing anyone. This goes to the deepest convictions. Do I have a moment here to say something on this?

Mr. Cameron: Yes.

President Dickey: I do want to say this, because we've been talking here about history and we've been talking about polls and majorities, and we've been talking about what we would do to meet future eventualities, but I would like to have every man here in the Dartmouth community realize that this is a question of things that relate to the deepest educational philosophy of an American institution of higher learning. America was founded on the proposition, and she's grown strong on the proposition, that men are accepted and judged on their individual merits. Now that's what is at issue here. I have never taken the position that we should have a policy that requires fraternities to take men they do not want. Personally all I want is that every Dartmouth social group may take or reject their members from the Dartmouth undergraduate body on the basis of the preferences and prejudices, if you will, of that group itself, rather than the preferences and prejudices of some very remote national charter written long before.

And there's something else that needs to be said here when we talk about postponement. The world has moved very fast and it has moved very far on these matters since 1954. Any person who overlooks that is simply out of touch with what's happening in the United States today. The Supreme Court decision on the issue of school segregation is only one evidence. The same is true in the area of international affairs, and if Dartmouth College, at this time, were to take a step back on this issue, Dartmouth College would be doing much more harm than anything that touches merely her fraternity system.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMy 65 Years as a Class Secretary

June 1959 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

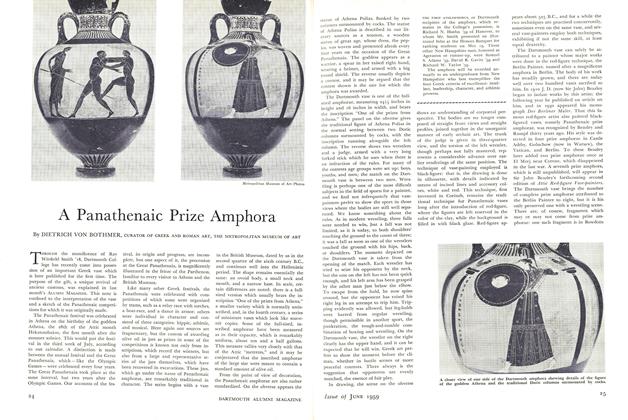

FeatureA Panathenaic Prize Amphora

June 1959 By DIETRICH VON BOTHMER -

Feature

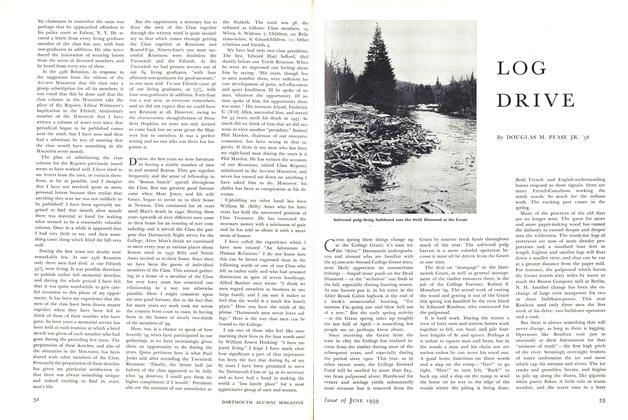

FeatureLOG DRIVE

June 1959 By DOUGLAS M. PEASE JR. '58 -

Feature

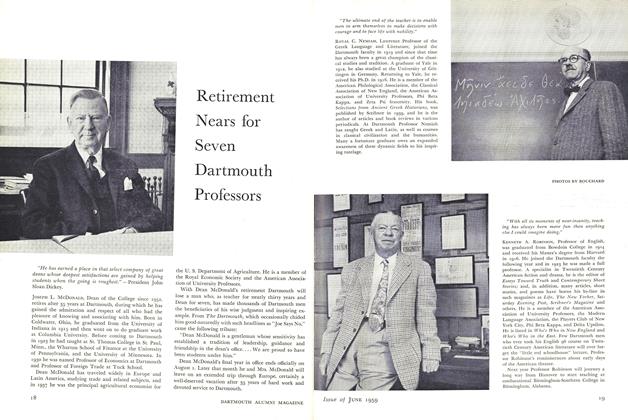

FeatureRetirement Nears for Seven Dartmouth Professors

June 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1959 By RONALD F. KEHOE '59 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

June 1959 By JOHN A. SAWYER, C. KIRK LIGGETT