AMERICAN colleges in the twentieth century have been unique for their concentration on mass education. While European universities have offered intensive high-quality training to a select few, our philosophy has been to give a liberal arts education to as many as possible. Today, though, we find our colleges turning more and more in the direction of quality to meet the challenges of the fast-moving modern age. Fortunately we have not been panicked into any ill-considered wholesale changes in our educational institutions merely to meet the temporary threat of Soviet Russian excellence. Dartmouth's answer to the challenge of the times, the "three-three" system, was conceived long before Sputnik came upon the scene.

This month marks the completion of the College's first full year under the new three-course, three-term curriculum. In any such far-reaching educational venture, the first year is bound to be crucial, for it is the time for setting goals and testing ideals against the exigencies of a practical situation. Reaching the end of this pioneer year, many students are looking back and evaluating the new system, weighing its accomplishments against its promise, and deciding for themselves. Best qualified to judge, perhaps, are those who have lived and studied under both the old and the new, since these men are closest to the implications of the change, in terms of study habits and patterns of living.

Administration feeling seems to be that the system can be evaluated best after one more year, when the members of the Class of 1960 have experienced two years of the new after two of the old. Next year some of the top College officers will seek opportunities to discuss the matter informally with small groups of undergraduates, listening and asking questions. Yet the new setup has been tried and judged with finality in the minds of many undergraduates.

Upperclassmen vary widely on the comparative benefits of the three-three system, but most will agree that it requires greater effort and more concentrated study per course. Course after course has been retooled to demand more of the student in the way of preparation. Some instructors use the so-called "X hour" each week to provide interested students with supplementary materials, such as films and recordings. This was done with particular success in the English Department's Shakespeare course.

Professors, too, are anything but unanimous about the effects of the curriculum on learning at the College. Most will grant that students seem to be working harder. Many remark that they themselves face a greater challenge and work load than before.

Heads of leading extracurricular organizations complain of new difficulties in recruiting heelers to staff their operations. Dartmouth has traditionally been heavily oriented toward the extracurricular, in line with the prevailing notion of the "whole man," and yet today the big student organizations are taxed to develop new ways of attracting recruits, and some of the smaller ones are teetering on the verge of extinction.

The College's social life is feeling the pinch to a lesser extent. Fraternity life remains vigorous and active, and many houses are more concerned about the 1960 Referendum than about the infringements of the three-three curriculum. Weekending, too, goes on as before. Green Key festivities last month attracted as many young ladies as usual, and the weekly exodus to more alluring spots south of Hanover is as great as any year in this writer's recall. The schedule dictates that nearly everyone must have at least one Saturday class, but resourceful undergraduates either cut class or, more often, depart Saturday forenoon for Northampton, Holyoke, or Boston. The greatest dissatisfaction with the new system's effect on social activity arose at Winter Carnival time. Carnival began on Friday this year, instead of earlier in the week, after exams ended, as under the two-semester setup. In a ten-week term, each class day counts so heavily that it is impossible to call a three-day winter holiday, and as a result Carnival is not what it used to be.

Scheduling is tight at the end of the term as well. Student tempers flared to find that even the two-day reading period of yore is gone. This term, for example, we plunge from Friday classes into Saturday exams, without even a Sunday breather.

The most obvious and least reliable indices of the new curriculum's impact are the statistics. Partisans of the system are gratified by the thirty percent increase in circulation of books in Baker Library and by the fifty percent rise in sales of noncourse paperbacks at the Dartmouth Bookstore. Unquestionably, Dartmouth students are now exposed to more reading material than ever before. Even the system's enemies must admit at the very least that more books are passing through undergraduate hands.

A very few students who enjoy close contact with faculty and administration have entertained the suspicion that the fundamental purpose that prompted the curriculum change was not an academic one at all. This group maintains that the top officials of the College were looking for a solution to the increasingly grievous problem of limited physical plant, as aggravated by the growing numbers of high school students qualified for admission. Several years ago Dartmouth Trustee Beardsley Ruml authored an article in The Atlantic stating the problem and proposing that American higher education must alter its traditional thinking to meet the challenge of the times. Specifically, Mr. Ruml predicted the twelvemonth academic year, resulting in a total enrollment increase of one third.

Recently the faculty authorized a committee to investigate the feasibility of establishing a full-scale coeducational (!) summer term at Dartmouth. Certainly one of the purposes of such a program will be to solve the logistics problems of operating the College during the summer. It is generally conceded that this is the forerunner of a regular summer term as part of the academic year. Once the details are worked out, Dartmouth is expected to shift to the "four-three" system of four terms per year and three courses per term. This will enable a given student to acquire his A.B. degree within three years, and it will end the present partial waste of College facilities. It may even be a pilot run for a coed Dartmouth!

But to return to the point. Admittedly the present system does distribute the load more evenly on the College's physical plant. Whether this and related benefits actually prompted the conception of the three-three curriculum, and whether the administration actually "maneuvered" its authorization through the faculty is not known. The critics claim that the academic ballyhoo of "independence in learning" and "the new Dartmouth" were mere sugar-coating to justify an educationally unwarranted change to the faculty. If this is the fact of the matter, it has been a well-kept secret.

But regardless of what were the compelling motivations behind the inception of a new curriculum at Dartmouth, we now have such a curriculum, and we should confine ourselves to examining the question of whether or not it works. If it accomplishes all or most of what it pretends to accomplish, it is successful.

For the most part, instructors are working more conscientiously than before. But as always in a community such as ours, there are exceptions. In this case there seems to be a general split between young and old. That is, the younger faculty men, who have shown most of the enthusiasm for the system in the first place, have been most willing to change their thinking and their approach to teaching to suit the system. As with all changes in human institutions, older men are often

more set in their ways and are more apt to resist change. Some professors, such as those having only a few years before retirement, see no reason to alter their methods of teaching or to discard the yellowed lecture notes.

The heart of the new system is the Independent Reading Program, whereby freshmen and sophomores must read certain works "with which a well-educated man should be familiar." Juniors and seniors read books prescribed by their particular departments of major study. By sponsoring lectures and radio discussions to supplement the reading, the Independent Reading Program has undertaken a vigorous attempt to make the concept work with the students. And yet, college students being what they are, all is not as it should be. Many men boast that they do no more than skim the required readings the night before the examination. This may be just stout, fashionable talk, but between increased course demands and the natural procrastination of college students, the Program is caught in a squeeze play. It requires a change of atmosphere, not just of mechanics, to encourage men to read for themselves. Certainly the Independent Reading Program is not "independent" to the extent that the College could confidently recommend the reading list without the enforcement device of an examination.

The most often cited indication of the new system's effects is, as we've noted, the statistics of book circulation, and yet this can be misleading if it is not properly qualified. For one thing, many courses require supplementary readings available only in Baker: English 2, for example, has a whole section of the Tower Room set aside for its outside readings, while Government 5 and 6 make extensive use of the Reserve Desk. As for paperback sales at the Bookstore, most of the increased non-course sales volume is accounted for by the Independent Reading Program. The point is that the students are in fact being exposed to more reading, but much of it results from class assignments, and not from individual initiative or curiosity.

The slogan for the three-three system is "independence in learning." The focus of Dartmouth's educational program is passing from instructor to student, from teaching to learning. Real learning is not to be served up to the passive undergraduate on the silver tray of a well-polished lecture. Rather, Dartmouth is now placing her faith in the belief that the most genuine learning results from independence, or self-dependence, to be more precise. Despite our qualifications, objections, and reservations, most of us will agree that we are learning more, and learning it a good deal more independently. However, this brings us to a really fundamental question that no one has really grappled with as yet.

The question mark has to do with the relation of independent learning to independent thinking. There is a gap between the two which we cannot simply assume is crossed because a new curriculum has been instituted. It is one thing to say that Dartmouth men are learning for themselves; it is an altogether different matter to say that they are thinking for themselves. One of the great questions of our time is conformity, particularly among the young men and women being produced by the country's colleges.

Conformity on the Dartmouth campus has been brought to light quite dramatically of late. With the revival of the Human Rights Society, a number of undergraduates have vocalized their antimilitarist pacifist feelings. During May a great debate raged in the Letters column of The Dartmouth, on the question of pacifism as an ethical and practical answer to the world situation. The pacifists turned out with placards to protest the Armed Forces Day ceremonies May 13. It is not particularly surprising that most undergraduates do not subscribe to the pacifist viewpoint. But it is indeed surprising, and disturbing as well, to realize that most students react with irritation when established conventions are questioned, and with scorn when rebels have the courage of their convictions by picketing a military ceremony on the Green. Most of the undergraduates have voluntarily put the blinders on and have closed their minds to unpopular thinking. In other words, the present-day student generation may be learning more independently, but it is not thinking independently by any means. What is worse, it even refuses to respect the independent thinking of a minority.

All of which brings us down to the basic question of the purposes of a liberal arts institution such as Dartmouth. It is generally supposed that the American college must take as its task both training and education: that is, it must prepare its undergraduates in both "conscience and competence," as President Dickey has phrased it. Is it possible that the new three-three system promotes learning at the expense of thinking, or competence at the expense of conscience? With less emphasis on the professor, the student has less opportunity for intellectual provocation in the realm of his personal values, and is thrown back all the more on whatever group he most associates with. The faculty has less opportunity these days to stimulate and challenge the student outlook. It has less time for "changing prejudice into judgment." Thus it is an unwarranted assumption that a successful shift to independent learning is to be equated with a coincident shift to independent thinking. The Tucker Foundation itself is a symbol of the College's recognition of this fact; the need is felt for an organized promotion of moral and ethical concern by students . . . concerns which the curriculum alone cannot adequately stimulate.

In conclusion, we might say that 1958-1959 has been one of the most exciting years in Dartmouth's long history. To some, it is the beginning of a whole new educational era, the College's entrance into a new dimension of excellence that will bring her to pre-eminence on the American educational scene. To others, it is somewhat less than that, in varying degrees depending on the commentator's perspective. Posterity will make the final judgment in its own good time. Meanwhile, Dartmouth must give her best to the new system, fulfilling as much of its potential as she can.

Dick Sanders '59 chopping away for Dartmouth in the Woodsmen's Weekend staged on the campus May 9 and won by Paul Smith's College. Dartmouth finished third.

Shattuck Observatory shown acquiring a new spring chapeau made of galvanized steel and rotated by electric power. The observatory's old wooden dome, dating from 1854, had to be rotated by hand on six pre-Civil War cannon balls serving as ball-bearings.

THE GUEST OCCUPANT of The Chair this month is Ronald F. Kehoe '59, an English honors student and until recently Manager of Station WDCR. A Phi Beta Kappa student, he has been awarded a Dartmouth General Fellowship for the study of law at Harvard.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMy 65 Years as a Class Secretary

June 1959 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

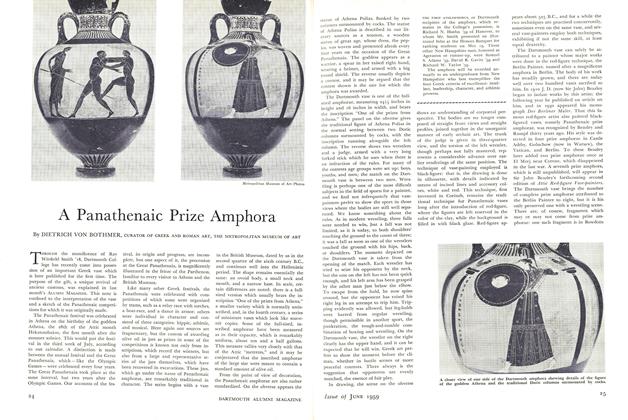

FeatureA Panathenaic Prize Amphora

June 1959 By DIETRICH VON BOTHMER -

Feature

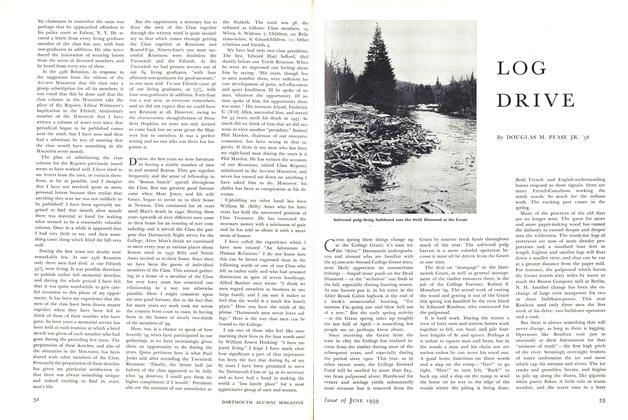

FeatureLOG DRIVE

June 1959 By DOUGLAS M. PEASE JR. '58 -

Feature

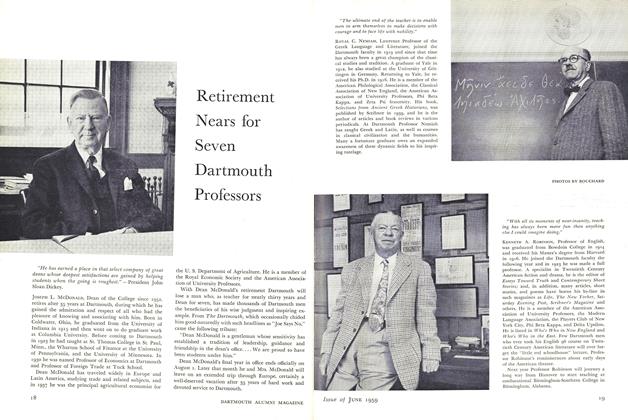

FeatureRetirement Nears for Seven Dartmouth Professors

June 1959 -

Article

ArticleThe Fraternity Discrimination Issue

June 1959 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

June 1959 By JOHN A. SAWYER, C. KIRK LIGGETT

RONALD F. KEHOE '59

Article

-

Article

ArticleSTEELE CHEMISTRY BUILDING FORMALLY DEDICATED OCT. 29

December 1921 -

Article

ArticleFeldman Named Dean

March 1940 -

Article

ArticleLecture Series

November 1946 -

Article

ArticleEberhart's "Fish Dinner"

OCTOBER, 1908 -

Article

ArticleThe First Lady's Organizer

May 1998 By Abigail Klingbeil '97 -

Article

ArticleWay Under the Volcano

NOVEMBER 1993 By Heather Killebrew '89