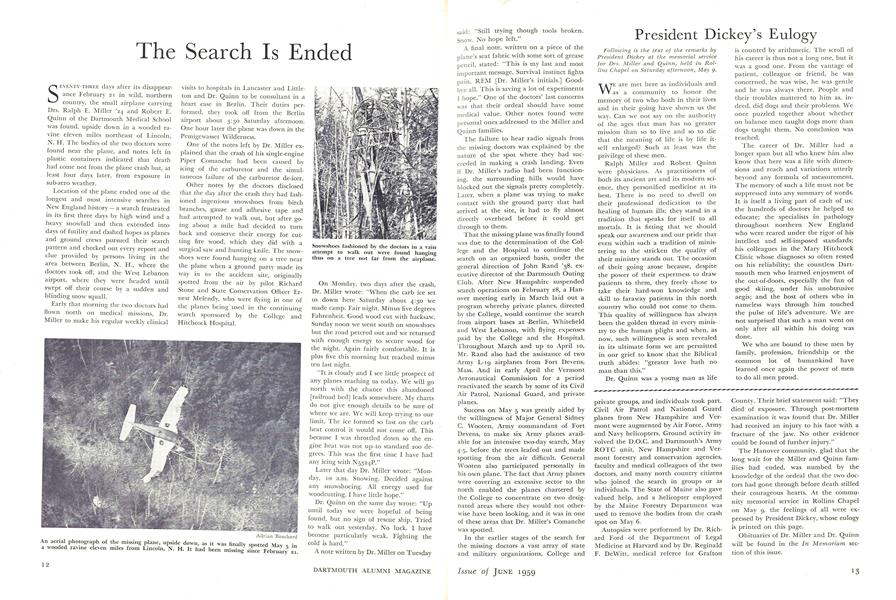

SEVENTY-THREE days after its disappearance February 21 in wild, northern country, the small airplane carrying Drs. Ralph E. Miller '24 and Robert E. Quinn of the Dartmouth Medical School was found, upside down in a wooded ravine eleven miles northeast of Lincoln, N. H. The bodies of the two doctors were found near the plane, and notes left in plastic containers indicated that death had come not from the plane crash but, at least four days later, from exposure in sub-zero weather.

Location of the plane ended one of the longest and most intensive searches in New England history - a search frustrated in its first three days by high wind and a heavy snowfall and then extended into days of futility and dashed hopes as planes and ground crews pursued their search pattern and checked out every report and clue provided by persons living in the area between Berlin, N. H., where the doctors took off, and the West Lebanon airport, where they were headed until swept off their course by a sudden and blinding snow squall.

Early that morning the two doctors had flown north on medical missions, Dr. Miller to make his regular weekly clinical visits to hospitals in Lancaster and Littleton and Dr. Quinn to be consultant in a heart case in Berlin. Their duties performed, they took off from the Berlin airport about 3:30 Saturday afternoon. One hour later the plane was down in the Pemigewasset Wilderness.

One of the notes left by Dr. Miller explained that the crash of his single-engine Piper Comanche had been caused by icing of the carburetor and the simultaneous failure of the carburetor de-icer.

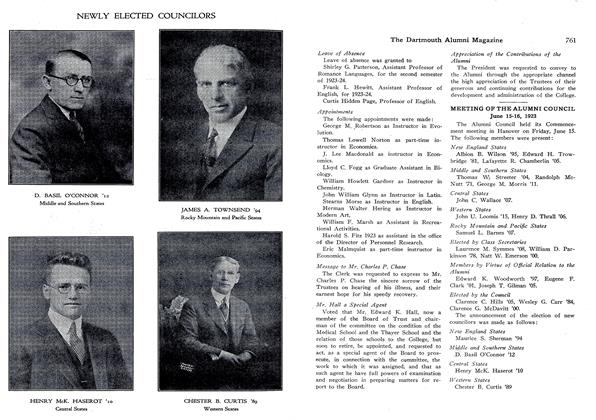

Other notes by the doctors disclosed that the day after the crash they had fashioned ingenious snowshoes from birch branches, gauze and adhesive tape and had attempted to walk out, but after going about a mile had decided to turn back and conserve their energy for cutting fire wood, which they did with a surgical saw and hunting knife. The snowshoes were found hanging on a tree near the plane when a ground party made its way in to the accident site, originally spotted from the air by pilot Richard Stone and State Conservation Officer Ernest Melendy, who were flying in one of the planes being used in the continuing search sponsored by the College and Hitchcock Hospital.

On Monday, two days after the crash, Dr. Miller wrote: "When the carb ice set us down here Saturday about 4:30 we made camp. Fair night. Minus five degrees Fahrenheit. Good wood cut with hacksaw. Sunday noon we went south on snowshoes but the road petered out and we returned with enough energy to secure wood for the night. Again fairly comfortable. It is plus five this morning but reached minus ten last night.

"It is cloudy and I see little prospect of any planes reaching us today. We will go north with the chance this abandoned [railroad bed] leads somewhere. My charts do not give enough details to be sure of where we are. We will keep trying to our limit. The ice formed so fast on the carb heat control it would not come off. This because I was throttled down so the engine heat was not up to standard 200 degrees. This was the first time I have had any icing with N5324P."

Later that day Dr. Miller wrote: "Monday, 10 a.m. Snowing. Decided against any snowshoeing. All energy used for woodcutting. I have little hope."

Dr. Quinn on the same day wrote: "Up until today we were hopeful of being found, but no sign of rescue ship. Tried to walk out yesterday. No luck. I have become particularly weak. Fighting the cold is hard."

A note written by Dr. Miller on Tuesday said: "Still trying though tools broken. Snow. No hope left."

A final note, written on a piece of the plane's seat fabric with some sort of grease pencil, stated: "This is my last and most important message. Survival instinct fights pain. REM [Dr. Miller's initials.] Goodbye all. This is saving a lot of experiments I hope." One of the doctors' last concerns was that their ordeal should have some medical value. Other notes found were personal ones addressed to the Miller and Quinn families.

The failure to hear radio signals from the missing doctors was explained by the nature of the spot where they had succeeded in making a crash landing. Even if Dr. Miller's radio had been functioning, the surrounding hills would have blocked out the signals pretty completely. Later, when a plane was trying to make contact with the ground party that had arrived at the site, it had to fly almost directly overhead before it could get through to them.

That the missing plane was finally found was due to the determination of the College and the Hospital to continue the search on an organized basis, under the general direction of John Rand '38, executive director of the Dartmouth Outing Club. After New Hampshire suspended search operations on February 28, a Hanover meeting early in March laid out a program whereby private planes, directed by the College, would continue the search from airport bases at Berlin, Whitefield and West Lebanon, with flying expenses paid by the College and the Hospital. Throughout March and up to April 10, Mr. Rand also had the assistance of two Army L-19 airplanes from Fort Devens, Mass. And in early April the Vermont Aeronautical Commission for a period reactivated the search by some of its Civil Air Patrol, National Guard, and private planes.

Success on May 5 was greatly aided by the willingness of Major General Sidney C. Wooten, Army commandant of Fort Devens, to make six Army planes available for an intensive two-day search, May 4-5, before the trees leafed out and made spotting from the air difficult. General Wooten also participated personally in his own plane. The fact that Army planes were covering an extensive sector to the north enabled the planes chartered by the College to concentrate on two designated areas where they would not otherwise have been looking, and it was in one of these areas that Dr. Miller's Comanche was spotted.

In the earlier stages of the search for the missing doctors a vast array of state and military organizations, College and private groups, and individuals took part. Civil Air Patrol and National Guard planes from New Hampshire and Vermont were augmented by Air Force, Army and Navy helicopters. Ground activity involved the D.O.C. and Dartmouth's Army ROTC unit, New Hampshire and Vermont forestry and conservation agencies, faculty and medical colleagues of the two doctors, and many north country citizens who joined the search in groups or as individuals. The State of Maine also gave valued help, and a helicopter employed by the Maine Forestry Department was used to remove the bodies from the crash spot on May 6.

Autopsies were performed by Dr. Richard Ford of the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard and by Dr. Reginald F. DeWitt, medical referee for Grafton County. Their brief statement said: "They died of exposure. Through post-mortem examination it was found that Dr. Miller had received an injury to his face with a fracture of the jaw. No other evidence could be found of further injury."

The Hanover community, glad that the long wait for the Miller and Quinn families had ended, was numbed by the knowledge of the ordeal that the two doctors had gone through before death stilled their courageous hearts. At the community memorial service in Rollins Chapel on May 9, the feelings of all were expressed by President Dickey, whose eulogy is printed on this page.

Obituaries of Dr. Miller and Dr. Quinn will be found in the In Memoriam section of this issue.

An aerial photograph of the missing plane, upside down, as it was finally spotted May a in a wooded ravine eleven miles from Lincoln, N.H. It had been missing since February 21.

Snowshoes fashioned by the doctors in a vain attempt to walk out were found hanging thus on a tree not far from the airplane.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMy 65 Years as a Class Secretary

June 1959 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

FeatureA Panathenaic Prize Amphora

June 1959 By DIETRICH VON BOTHMER -

Feature

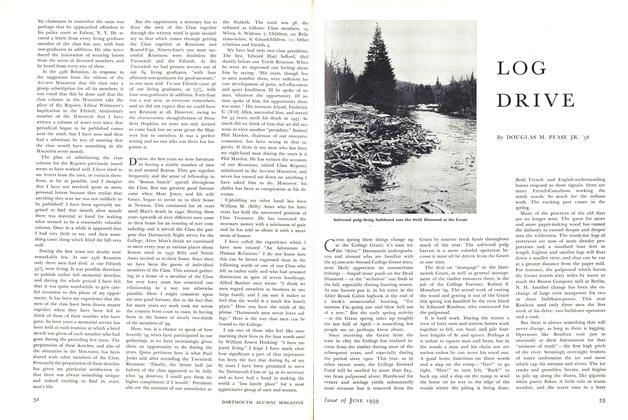

FeatureLOG DRIVE

June 1959 By DOUGLAS M. PEASE JR. '58 -

Feature

FeatureRetirement Nears for Seven Dartmouth Professors

June 1959 -

Article

ArticleThe Fraternity Discrimination Issue

June 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1959 By RONALD F. KEHOE '59