ALL OVER the United States, undergraduate marriages are increasing, not only in the municipal colleges and technical schools, which take for granted a workaday world in which learning is mostly training to make a living, but also on the green campuses once sacred to a more leisurely pursuit of knowledge.

Before we become too heavily committed to this trend, it may be wise to pause and question why it has developed, what it means, and whether it endangers the value of undergraduate education as we have known it.

The full-time college, in which a student is free for four years to continue the education begun in earlier years, is only one form of higher education. Technical schools, non-residence municipal colleges, junior colleges, extension schools which offer preparation for professional work on a part-time and indefinitely extended basis, institutions which welcome adults for a single course at any age: all of these are "higher," or at least "later," education. Their proliferation has tended to obscure our view of the college itself and what it means.

But the university, as it is called in Europe - the college, as it is often called here - is essentially quite different from "higher education" that is only later, or more, education. It is, in many ways, a prolongation of the freedom of childhood; it can come only once in a lifetime and at a definite stage of development, after the immediate trials of puberty and before the responsibilities of full adulthood.

The university student is a unique development of our kind of civilization, and a special pattern is set for those who have the ability and the will to devote four years to exploring the civilization of which they are a part. This self-selected group (and any other method than self- selection is doomed to failure) does not include all of the most able, the most skilled, or the most gifted in our society. It includes, rather, those who are willing to accept four more years of an intellectual and psychological moratorium, in which they explore, test, meditate, discuss, passionately espouse, and passionately repudiate ideas about the past and the future. The true undergraduate university is still an "as-if" world in which the student need not commit himself yet. For this is a period in which it is possible not only to specialize but to taste, if only for a semester, all the possibilities of scholarship and science, of great commitment, and the special delights to which civilized man has access today.

One of the requirements of such a life has been freedom from responsibility. Founders and administrators of universities have struggled through the years to provide places where young men, and more recently young women, and young men and women together, would be free - in a way they can never be free again - to explore before they settle on the way their lives are to be lived.

This freedom once, as a matter of course, included freedom from domestic responsibilities - from the obligation to wife and children or to husband and children. True, it was often confused by notions of propriety: married women and unmarried girls were believed to be improper dormitory companions, and a trace of the monastic tradition that once forbade dons to marry lingered on in our men's colleges. But essentially the prohibition of undergraduate marriage was part and parcel of our belief that marriage entails responsibility.

A student may live on a crust in a garret and sell his clothes to buy books; a father who does the same thing is a very different matter. An unmarried girl may prefer scholarship to clerking in an office; as the wife of a future nuclear physicist or judge of the Supreme Court - or possibly of the research worker who will find a cure for cancer - she acquires a duty to give up her own delighted search for knowledge and to help put her husband through professional school. If, additionally, they have a child or so, both sacrifice - she her whole intellectual interest, he all but the absolutely essential professional grind to "get through" and "get established." As the undergraduate years come to be primarily not a search for knowledge and individual growth, but a suitable setting for the search for a mate, the proportion of full-time students who are free to give themselves the four irreplaceable years is being steadily whittled down.

SHOULD WE MOVE so far from the past that all young people, whether in college, in technical school, or as apprentices, expect to be married and, partially or wholly, to be supported by parents and society while they complete their training for this complex world? Should undergraduates be considered young adults, and should the privileges and responsibilities of mature young adults be theirs, whether they are learning welding or Greek, bookkeeping or physics, dressmaking or calculus? Whether they are rich or poor? Whether they come from educated homes or from homes without such interests? Whether they look forward to the immediate gratifications of private life or to a wider and deeper role in society?

As one enumerates the possibilities, the familiar cry, "But this is democracy," interpreted as treating all alike no matter how different they may be, assaults the ear. Is it in fact a privilege to be given full adult responsibilities at eighteen or at twenty, to be forced to choose someone as a lifetime mate before one has found out who one is, oneself - to be forced somehow to combine learning with earning? Not only the question of who is adult, and when, but of the extent to which a society forces adulthood on its young people, arises here.

Civilization, as we know it, was preceded by a prolongation of the learning period—first biologically, by slowing down the process of physical maturation and by giving to children many long, long years for many long, long thoughts; then socially, by developing special institutions in which young people, still protected and supported, were free to explore the past and dream of the future. May it not be a new barbarism to force them to marry so soon?

"Force" is the right word. The mothers who worry about boys and girls who don't begin dating in high school start the process. By the time young people reach college, pressuring parents are joined by college administrators, by advisers and counselors and deans, by student-made rules about exclusive possession of a girl twice dated by the same boy, by the preference of employers for a boy who has demonstrated a tenacious intention of becoming a settled married man. Students who wish to marry may feel they are making magnificent, revolutionary bids for adulthood and responsibility; yet, if one listens to their pleas, one hears only the recited roster of the "others" - schoolmates, classmates, and friends - who are "already married."

The picture of embattled academic institutions valiantly but vainly attempting to stem a flood of undergraduate marriages is ceasing to be true. College presidents have joined the matchmakers. Those who head our one-sex colleges worry about transportation or experiment gingerly with ways in which girls or boys can be integrated into academic life so that they'll stay on the campus on weekends. Recently the president of one of our good, small, liberal arts colleges explained to me, apologetically, "We still have to have rules because, you see, we don't have enough married-student housing." The implication was obvious: the ideal would be a completely married undergraduate body, hopefully at a time not far distant.

With this trend in mind, we should examine some of the premises involved. The lower-class mother hopes her daughter will marry before she is pregnant. The parents of a boy who is a shade gentler or more interested in art than his peers hope their son will marry as soon as possible and be "normal." Those who taught GI's after the last two wars and enjoyed their maturity join the chorus to insist that marriage is steadying: married students study harder and get better grades. The worried leaders of one-sex colleges note how their undergraduates seem younger, "less mature," or "more underdeveloped" than those at the big coeducational universities. They worry also about the tendency of girls to leave at the end of their sophomore year for "wider experience" - a simple euphemism for "men to marry."

And parents, who are asked to contribute what they would have contributed anyway so that the young people may marry, fear - sometimes consciously and sometimes unconsciously—that the present uneasy peacetime will not last, that depression or war will overtake their children as it overtook them. They push their children at even younger ages, in Little Leagues and eighth-grade proms, to act out - quickly, before it is too late - the adult dreams that may be interrupted. Thus they too consent, connive, and plan toward the earliest possible marriages for both daughters and sons.

UNDERGRADUATE MARRIAGES have not been part of American life long enough for us to be certain what the effect will be. But two ominous trends can be noted.

One is the "successful" student marriage, often based on a high-school choice which both sets of parents have applauded because it assured an appropriate mate with the right background, and because it made the young people settle down. If not a high-school choice, then the high-school pattern is repeated: finding a girl who will go steady, dating her exclusively, and letting the girl propel the boy toward a career choice which will make early marriage possible.

These young people have no chance to find themselves in college because they have clung to each other so exclusively. They can take little advantage of college as a broadening experience, and they often show less breadth of vision as seniors than they did as freshmen. They marry, either as undergraduates or immediately upon graduation, have children in quick succession, and retire to the suburbs to have more children - bulwarking a choice made before either was differentiated as a human being. Help from both sets of parents, begun in the undergraduate marriage or after commencement day, perpetuates their immaturity. At thirty they are still immature and dependent, their future mortgaged for twenty or thirty years ahead, neither husband nor wife realizing the promise that a different kind of undergraduate life might have enabled each to fulfill.

Such marriages are not failures, in the ordinary sense. They are simply wasteful of young, intelligent people who might have developed into differentiated and conscious human beings. But with four or five children, the husband firmly tied to a job which he would not dare to leave, any move toward further individual development in either husband or wife is a threat to the whole family. It is safer to read what both agree with (or even not to read at all and simply look at TV together), attend the same clubs, listen to the same jokes - never for a minute relaxing their possession of each other, just as when they were teen-agers.

Such a marriage is a premature imprisonment of young people, before they have had a chance to explore their own minds and the minds of others, in a kind of desperate, devoted symbiosis. Both had college educations, but the college served only as a place in which to get a degree and find a mate from the right family background, a background which subsequently swallows them up.

The second kind of undergraduate marriage is more tragic. Here, the marriage is based on the boy's promise and the expendability of the girl. She, at once or at least as soon as she gets her bachelor's degree, will go to work at some secondary job to support her husband while he finishes his degree. She supports him faithfully and becomes identified in his mind with the family that has previously supported him, thus underlining his immature status. As soon as he becomes independent, he leaves her. That this pattern occurs between young people who seem ideally suited to each other suggests that it was the period of economic dependency that damaged the marriage relationship, rather than any intrinsic incompatability in the original choice.

Both types of marriage, the "successful" and the "unsuccessful," emphasize the key issue: the tie between economic responsibility and marriage in our culture. A man who does not support himself is not yet a man, and a man who is supported by his wife or lets his parents support his wife is also only too likely to feel he is not a man. The GI students' success actually supports this position: they had earned their GI stipend, as men, in their country's service. With a basic economic independence they could study, accept extra help from their families, do extra work, and still be good students and happy husbands and fathers.

THERE ARE, then, two basic conclusions. One is that under any circumstances a full student life is incompatible with early commitment and domesticity. The other is that is is incompatible only under conditions of immaturity. Where the choice has been made maturely, and where each member of the pair is doing academic work which deserves full support, complete economic independence should be provided. For other types of student marriage, economic help should be refused.

This kind of discrimination would remove the usual dangers of parent-supported, wife-supported, and too-much- work-supported student marriages. Married students, male and female, making full use of their opportunities as undergraduates, would have the right to accept from society this extra time to become more intellectually competent people. Neither partner would be so tied to a part-time job that relationships with other students would be impaired. By the demands of high scholarship, both would be assured of continued growth that comes from association with other high- caliber students as well as with each other.

But even this solution should be approached with caution. Recent psychological studies, especially those of Piaget, have shown how essential and precious is the intellectual development of the early post-pubertal years. It may be that any domesticity takes the edge off the eager, flaming curiosity on which we must depend for the great steps that Man must take, and take quickly, if he and all living things are to continue on this earth.

Cornell Capa, Magnum

Copyright i960 by Editorial Projects for Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor Jesup's Herbarium

March 1960 By JAMES P. POOLE -

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60 -

Feature

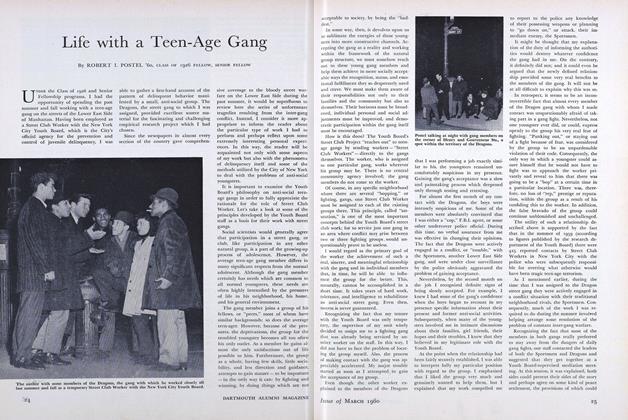

FeatureLife with a Teen-Age Gang

March 1960 By ROBERT I. POSTEL '60 -

Article

ArticleThe Mission of Liberal Learning

March 1960 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, ROBERT FISH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

March 1960 By RICHARD W. BALDWIN, IRA L. BERMAN

Features

-

Feature

Feature'59 GETS STARTED

October 1955 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAndrew Asnes '86

March 1993 -

Feature

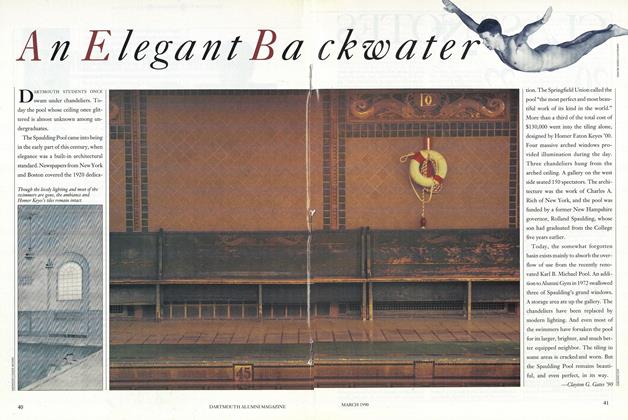

FeatureAn Elegant Backwater

MARCH 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Feature

FeatureA Season on the Racetrack Special

January 1976 By DAVID DUNBAR -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

FEBRUARY 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55 -

Feature

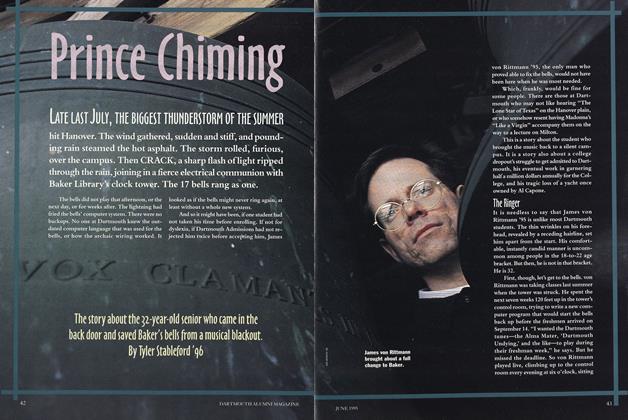

FeaturePrince Chiming

June 1995 By Tyler Stableford '96