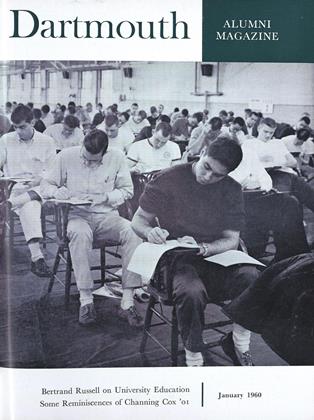

Who's "Chub" Feeney? Anyone in the early '4os, standing at the Inn corner, could have had the answer from any passerby well, maybe not the Hrst one but certainly the second or third. Nowadays the name is rapidly picking up circulation'in and around San Francisco. Bound to be so inasmuch as Charles Stoneham Feeney '43, vice-president of San Francisco's National League Giants, can't very well avoid being quoted by West Coast beaver-busy sports writers. So, how come? Well, it's just another parallel between campus and business careers. Chub Feeney's case, however, merits more than casual glance because college men aren't often found sitting at pro-sports business desks.

Chub dates his awakening to baseball's values back to 1933 when, aged 12, he saw the Giants win the World Series 4-1 from Washington's Senators (two of the games were won by pitcher Carl Hubbell, today in charge of the Giants' farm system clubs). Colorful Bill Terry, lifetime batting average .341, was player-manager. So, the boy Feeney became a student of the illustrious Giants and their storied past such as the up and down days under fiery field manager John McGraw when the Giants, league champs in 1912 and 1913, dropped to second place in 1914, to the cellar in 1915, struggled back to fourth place in 1916, and then regained the "champeenship" in 1917.

This was the era when Boston's Red Sox became New England's favorite and Dartmouth players dared aspire to a "try-out" with them inasmuch as the Red Sox had signed up Ralph "Pitcher" Glaze '06, more notable on the gridiron than the diamond.

One of the most dramatic of World Series was that of 1912 between the Giants and the Red Sox. Charles Monroe (Jeff) Tesreau, Giants' leadoff pitcher, was opposed by the great Smoky-Joe Wood, whose phenomenal season record was 34 won, 5 lost. In this series Wood won the first and fourth games, 4-3 and 3-1, against Tesreau, and the latter beat him 11-4 in the seventh game. A tie game forced the series to an eighth contest, played in Boston, and it was in this game that the Giants' Fred Snodgrass made his notorious muff of an easy fly ball. Boston won this title-deciding game when Chief Meyers, Dartmouth '09, and Fred Merkle let a simple foul ball, -good for a second out, fall between them, permitting one Yerkes to score the winning tally from third base on a fly-out by the great Larry Gardner, University of Vermont star '05-'07 and later their greatly beloved coach.

What has this ancient lore to do with l eeney '43? Just this: he had been named for his grandfather, "Charlie" Stoneham, financier of the Giants, who held that no boy was all boy unless he had a yen to be a baseball star. Well, some boys are gaited to organize and manage and some boys are gifted with the physical coordination of a ballplayer . . . it's as simple as that. On the diamond Chub Feeney just couldn't sparkle.

So, stepping along a few years, here he is moving up from Columbia High, Maplewood, N. J., to the Hanover campus. It wasn't long before a pathway opened up and beckoned. In sophomore year he "went out for" an athletic managership and, as Horatio Alger would say, by pluck and luck he was chosen up-coming assistant manager of baseball. This led, of course, in senior year to manager and thereby an extracurricular course of solid value to Feeney. Along the way he had picked up the ribands of Palaeopitus, Green Key, Phi Kappa Psi, C&G. Also he was to be exposed to a course in crowd management when elected head usher for all college foregatherings.

As baseball manager he was working hand in glove with famous "Jeff" Tesreau, coach at Dartmouth from 1919 until his death on Sept. 24, 1946. Instructor Tesreau's textbook was "the way we did it with the Giants." In essence, instruction centered on how to establish and nurture a tradition of victory. The secret ingredients of this savory dish included consistent awareness, the importance of detail and, above all, sustained effort game by game, season by season. Also, there were the chapters on equipment purchasing, how to transport and lodge an athletic team, what to insist upon, and what to avoid, etc. At graduation Chub was ready for the call to the colors.

Following some two and a half years with the Navy in World War 11, he prepared for entrance to business at Fordham Law School and passed the stiff New York State bar exams. But the family baseball tradition could not be gainsaid and his law training is employed today for the most part in drawing up contractile documents. Also, with his legal language training, he is a natural as one of nine members of the Rules Committee that governs the playing of the national sport today.

What of professional sports as a career for college men? As Feeney '43 views the outlook, professional sports are indeed a profession and involve years of arduous training and experience. The precision of skill essential to the big-league baseball player today, eligible as he must be for ranking as one of the world's most proficient, requires the all-embracing training that serves, as the saying goes, to separate the men from the boys. For that very reason the youth who enters baseball direct from high school and at his most adaptable age, enjoys a four-year advantage over the average good college player. For the records indicate that even the so-called natural ball player can acquire the required techniques and semi-automatic mental reactions of the true pro only by a gradual advance through the grades of the minor leagues.

There is no more absorbing, fascinating, albeit difficult task than the choosing-up of a group of athletes to be molded into a team, finely balanced in its skills on defense and on attack. A major segment of Feeney's hours, almost 'round-the-clock, is devoted to weighing opinions and judgments of quasi-committees made up of President Horace Stoneham, field-manager Rigney, the coaches, and field scouts, against the valuation of his own skills by the player to be employed. For there is no unionized player, no established scale of pay for second basemen, catchers, pitchers, etc. Thus, the underlying and fixed requirements must be adequate yet sound financial incentive for the player and a balanced budget in the business office.

In the process of this meeting of minds, especially when one is dealing often with temperamental "artists" (and they have their advisers), the man behind the desk in addition to decimal efficiency must employ the subliminal skills, the skills of the spirit.

O.K., how's Chub doing? That depends upon whether you measure his wealth by all assets or by money in the bank. Like most folks he hasn't enough in the bank. Never theless, in the column of assets including health, family, clearly defined goals and know-how, Chub is doing O.K. Of course, as a boy he realized that he would never be a handy-Andy athletically; his friends continue cheerfully to concede him a 17-stroke handicap in golf.

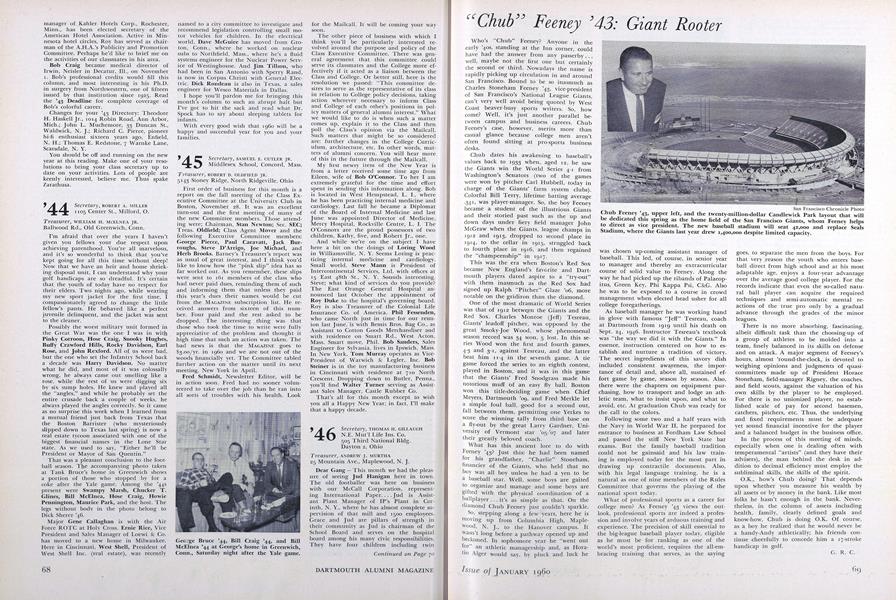

Chub Feeney '43, upper left, and the twenty-million-dollar Candlewick Park layout that wil be dedicated this spring as the home field of the San Francisco Giants, whom Feeney helps to direct as vice president. The new baseball stadium will seat 42,000 and replace Seals Stadium, where the Giants last year drew 1,400,000 despite limited capacity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"As I Remember..."

January 1960 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureDemocracy's Influence on University Education

January 1960 By BERTRAND RUSSELL -

Feature

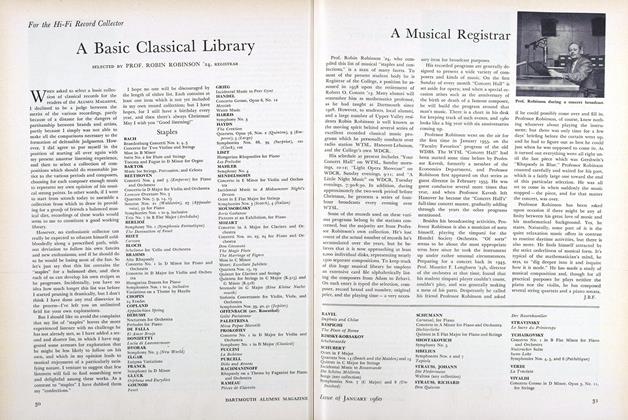

FeatureA Basic Classical Library

January 1960 By PROF. ROBIN ROBINSON '24 -

Article

ArticleA Famed Collection and How It Grew

January 1960 By EVELYN STEFANSSON -

Article

ArticleReligion in the Soviet Union

January 1960 By HENRY S. ROBINSON '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER