IN a unique and pioneering educational experiment, fifty outstanding American and British motion pictures of the past will be shown free of charge to Dartmouth students during the 1960-61 academic year. The experiment, beginning its second year on the campus, is called the Dartmouth Daily Film Program and is designed, in the words of its faculty chairman, Prof. Benfield Pressey, "to supplement academic work by drawing on varieties of individual and social experience which have been portrayed in motion pictures."

The idea of showing worthwhile films as an addition to the curriculum was put forward by the late Beardsley Ruml '15, Life Trustee of the College, in the fall of 1959. He believed that the motion picture could valuably supplement the usual academic learning and that the large library of Hollywood films, available in 16 mm. prints, could illustrate various worthy ideas and concepts. Such a program, he felt, could also demonstrate the kind of film program the Hopkins Center might offer when it is completed, and provide experience in managing such a program.

With this basic idea, an advisory board was formed to bring the project closer to reality. With Mr. Ruml participating, it included such film experts as Arthur Hornblow Jr. '15, producer of many of the best MGM films, chairman; Bosley Crowther, film critic of The New YorkTimes; Arthur Mayer, author and film importer; and the well-known Hollywood director, Fred Zinnemann.

This group met a year ago to discuss the aims of such a program, and suggested many ways of directing such a novel project. In addition, each man suggested a number of films he thought would best illustrate the aims for which he felt the daily film program should strive.

Shortly after this first meeting, a similar group was organized in Hanover under the direction of Professor Pressey, who had taught a course in screenwriting at Dartmouth. Other members of the Hanover committee included Orton H. Hicks '21, vice-president of the College and former MGM executive; J. Blair Watson, audio-visual director of Dartmouth College; Kenneth Dimick, manager of The Nugget; and the author of this article, who at the time was the undergraduate director of the Dartmouth Film Society.

This group first had to decide how to fit the new program into the film situation in Hanover. Feature films could be seen in several ways. The Nugget provides a commercially selected program of the best of the new American and foreign films. The Film Society, with membership numbering close to 300, provides more esoteric fare, including foreign language films, experimental films, and silent films, as well as the more unusual film classics. The Hanover committee decided, therefore, to confine the Daily Film Program to American and British films no longer being exhibited in commercial theaters.

The committee decided early to announce that the program would undertake to provide films which would give educational experiences, films which would illustrate certain truths of morality, widen understanding of human character, and inform and enlighten the student in other ways. This criterion was difficult to follow, but it reflected the noble ambitions of the program.

This led, naturally enough, into the selection of the films. The committee members were provided with the list of titles suggested by the New York advisory board. Each film was briefly described, and valued in terms of its relation to a given educational area. In addition, each member of the Hanover committee suggested his favorites. Every film was discussed and the list was carefully reduced to about fifty titles, of which 34 were programmed for the 1960 winter and spring terms. No silent or foreign language films were included, since the need for these was filled by the Film Society.

Since Fairbanks Hall, where 16 mm. films are usually shown, seats only 98 viewers, each film had to be shown several times. The committee decided further to show two films a week, one running from Sunday to Tuesday, the second from Wednesday to Saturday, excluding Thursday, the Film Society day. Sunday showings were scheduled for 1:30 and 4 p.m; Monday 1:30 p.m.; Tuesday 4 p.m.; Wednesday 4 p.m.; Friday 1:30 p.m.; and Saturday 1:30, 4 and 10:30 p.m., the last program being held in Dartmouth Hall to accommodate crowds returning from sports and other events at that hour.

For each film, this writer provided program notes, which, if his enthusiasm did not run away with him, provided a short background to the film, underlining its particular value. An audience is far more appreciative of a film when it realizes that the weaknesses of the film have been discovered by someone else, and accepted along with its strengths. A young audience should be reminded that some of the best films of all time have dated noticeably over the years, and this was often accomplished by the program notes.

First public announcement of the Dartmouth Daily Film Program (later to be known colloquially as the "free flicks") was made in The Dartmouth on Friday, January 8, and the experiment began on Sunday with Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940). Due to the newness of the program, the first showings were poorly attended, but by the next weekend 675 students had seen The Grapes of Wrath (1940), and the series was on its way. Daily announcements of the films were carried in The Dartmouth and over the campus radio station, WDCR, as well as in the weekly College Bulletin.

During the winter and spring terms the films were shown in no particular order. But every film shown bore upon the work of some course or department, and in advance of the showings the committee would notify by postcard the course instructor or the department head, with a reminder of the times and places of showing and a request that he inform his students.

For this year's series, the entire list of proposed films was mailed to the faculty in July and they were asked to indicate the term in which a particular film would be of greatest value to their classes, and also to make suggestions. In response, at least twenty films were scheduled at times when they would be of specific educational value, an improvement over the previous programming.

The first two terms were a real experiment, and the results were curious and often exciting. For instance, the reaction to Orson Welles' version of Shakespeare's Othello, a film which was unable to find a single commercial distributor at the time of its completion some five years ago. The play was familiar to those who had read it in Freshman English, and though the film may be said to contain more Welles than Shakespeare, it apparently was a genuinely exciting experience to those who saw it. Requests were made for more Shakespeare, and the 1960-1961 program includes A MidsummerNight's Dream (1935), Romeo and Juliet (1935), The Taming of the Shrew (1929), and Hamlet (1948).

Among social-problem films, TheGrapes of Wrath, Intruder in the Dust (1949), and They Won't Forget (1937) were well attended, and apparently the lessons explicit in these films were sympa-thetically received by the audiences. A few eyebrows were raised at the programming of Them (1954), a better-than-average science-fiction thriller that 785 persons attended. However, the committee felt that the science-fiction film is an interesting commentary on modern-day life, and examples should be included.

The best attendance figures were recorded at The Grapes of Wrath, TheDam Busters (1955), The Snake Pit (1948), Them, The Barretts of WimpoleStreet (1957), All About Eve (1950), Camille (1936), A Time to Love and aTime to Die (1958), Captain Courageous (1937), Citizen Kane (1941), Kim (1950), Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), The Living Desert (1953), The AsphaltJungle (1950), A Tale of Two Cities (1935), and Singing in the Rain (1952).

Audiences avoided Across the WideMissouri (1951), The Actress (1955), I Remember Mama (1948), Cass Timberlane (1947), and the beautiful Swedish nature film, The Great Adventure (1955). These titles may be replaced on future lists, or special publicity prepared to popularize them.

According to a questionnaire administered by James A. Nolan '61 in May, under the direction of Prof. George F. Theriault of the Sociology Department, the quality of the films shown in the series was recognized and appreciated by the student body. Only three films received much adverse criticism: Camille, which quite frankly shows its age, DavidCopperfield (1935), also a bit dated, and John Ford's My Darling Clementine (1946), a Western admired by critics but not by undergraduates. Although most of the students polled stated that they attended a particular movie for entertainment, additional comments indicated that many discovered the motion picture could also be intellectually stimulating. And many expressed appreciation that some of the old film classics could be seen again.

A persistent problem in the direction of the program is the unavailability of certain films that are requested and worthy of showing. Most large film producers have outlets which distribute 16 mm. rental copies of their films, the largest being Films Incorporated, source of many of the first year's films. However, many pre-1948 films were withdrawn from 16 mm. circulation when prints were sold to television. With the sale of post-1948 titles in recent months, the situation will probably worsen. Almost anything made at the Paramount studios, including numerous requested films, is unavailable.

Sometimes a request to the producing company brings results, and thanks to their cooperation, Dartmouth audiences will soon be able to enjoy such long-out-of-print classics as Fury (1936), TheCitadel (1936), and Garbo in AnnaKarenina (1935). Yet dozens more remain tantalizingly unavailable, including most of the George Bernard Shaw films (due to a legal controversy over who owns the rights), and such films as AConnecticut Yankee, In Which We Serve, the Olivier-Bergner As You Like It,Mourning Becomes Electra, Yankee Doodle Dandy, Street Scene, and Garbo in Pirandello's As You Desire Me, all requested at one time or another.

For the current fall term the films scheduled are The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941), I A m a Fugitive from aChain Gang (1932), Stanley and Livingston (1939), Black Legion (1936), ThePresident Vanishes (1935), Dead of theNight (1945), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Wilson (1944), Black-Fury (1935), Our Daily Bread (1934), The Red Badge of Courage (1950), ATime to Love and a Time to Die (1957), Battleground (1949), and Miracle on34th Street (1947).

The winter-term schedule will include three Dickens films, Great Expectations (1947), Nicholas Nickleby (1947) and Oliver Twist (1949); and four Shakespeare plays, A Midsummer Night'sDream (1935), Romeo and Juliet (1935), The Taming of the Shrew (1929), and Hamlet (1948).

The 1960-1961 series has benefited from the past year's experience and has taken advantage of many thoughtful suggestions from faculty and students alike. It reflects the seriousness and depth of purpose which will make the program of continuing value to its audience. Very likely this pioneering effort in integrating the best of American and British films into the broad purposes of the Dartmouth liberal education will serve to stimulate similar film programs at other colleges.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIt Was A Dartmouth Jinx All the Time

November 1960 By AMOS N. BLANDIN '18 -

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

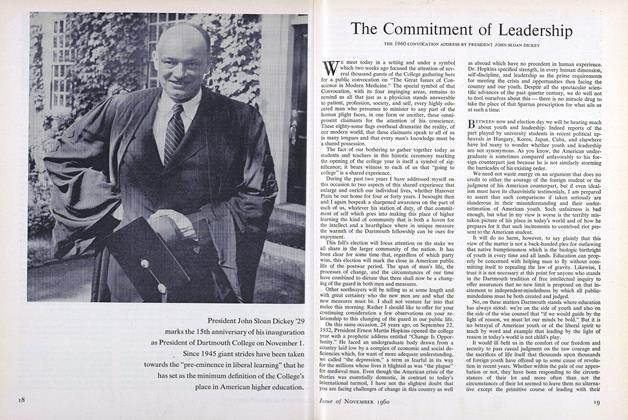

FeatureThe Commitment of Leadership

November 1960 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

Feature"The Era of the Shrug"

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleEvening Assembly

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleSecond Panel Discussion

November 1960