Following is the nearly full text of the address deliveredby President Dickey on October 22, at the inaugurationof Robert Kenneth Carr '29 as President of Oberlin College.

MAY I use this happy moment symbolizing the meeting of man and institution to raise for your consideration a perplexity which is close to the heart of all undergraduate institutions in America today and therefore a needful concern of all who are committed to the work of higher learning at whatever level or post of duty.

I cannot do much more here than to put the question which broadly stated is: Can an overarching sense of institutional purpose be retained in today's college as a major factor in the educational experience of our undergraduates?

I make bold to raise this question here because, without knowing your situation as intimately as I should like, I suspect that Oberlin like Dartmouth and other generally similar institutions faces perplexities on this score which, as I said, go to the heart of our convictions and our efforts. Let me also say that I am here addressing myself mainly to undergraduate education and particularly to the independent college. Even though there is an unmistakable tendency throughout all education toward permitting qualified individuals to bridge the arbitrary divisions between school and college and between undergraduate and graduate work, I am sure that an institution such as Oberlin's still has the possibility of using a focused sense of institutional purpose as a factor in its educational process to a degree that is now denied many of our great universities.

The great university with its dozens of separate schools and units, its students numbered in the tens of thousands, its staff counted by thousands, and its sense of place inevitably fractured and dispersed, by the very nature of things can rarely hope to invoke a sharply defined sense of institutional purpose as a major factor in the educational experience of its undergraduates. I do not assert it is impossible; I merely say that this particular possibility is difficult to the point of being unlikely under the circumstances of life and work that govern in most great universities today. It is no mere politeness to add that these great educational enterprises have their own peculiar strengths that conversely are denied or are difficult in the independent college. I would like to be clear that it is no part of my intention today to weigh the comparative merits of these varying institutions for undergraduate education; it is more than enough for this occasion to address ourselves to our own particular perplexity and I make this brief reference to the situation of the universities only to sharpen the focus of our attention to the college.

One thing is certain, we cannot hope to get any mileage out of an institutional sense of purpose unless we have such a purpose. I shall not presume to tell you what your sense of institutional purpose is or should be, but it is surely due you that I should not leave this critical aspect of the matter without avowing my own convictions.

Although I am a benignly disposed skeptic concerning the current fashion for reducing all that is America to panel packaged purposes, I am not one who despairs of being able to find at least a focus of purpose within the life and work of a liberal arts college. I believe it is the purpose of liberal learning to liberate. As in other human organisms, the historic American college has a heritage that I find immensely helpful in understanding the deepest, almost instinctive, purposes of the college. In this heritage I find a constant, explicit concern that a college education should enlarge both man's competence and his goodness. Both is the key word. It is in this bond of indissoluble marriage between competence and conscience that I find the unique institutional validity of the historic American college. Individuals hopefully serve both purposes wherever they are, but other institutions properly focus primarily or solely on one or the other of these two poles of educational purpose. At the highest levels of organized education, the college, at least up to now, has been the last institutional embodiment of these dual purposes.

As many of you know more intimately than I, this sense of dual purpose historically found expression in varying ways, just as today's threat to it has many causes.

The dispersed and reduced position of formal religion in secular higher education is the most conspicuous and probably the most powerful negative factor in the progressive weakening we are witnessing in the college's sense of a dual purpose. This negative factor is paralleled on the positive side by the rise of a philosophy of pluralism and relativism that while nurturing the imperatives of specialized scholarship has so far proved a thin and acid soil for any new growth of institutional purpose.

The way forward in this, as in all else, is not to be seen in the rear-view mirror. My only other certainty about the matter is that we will work at finding creative answers only if we begin to see what is at stake. The central point is this: a worthy sense of institutional purpose can be tomorrow, as it was yesterday, both a powerful factor in the educational experience of the individual undergraduate and the best insurance all higher education can buy against its ancient foe and greatest danger - the perversion of knowledge. May it not be that retention of an articulate institutional purpose is the only significant thing that stands between the college and the mistaken view that increasingly sees and judges these enterprises of learning primarily in terms appropriate to a university?

Parenthetically, let me say that although I think the issue of bigness versus smallness is often overstated and oversimplified, I do recognize that size is a factor that bears on the effectiveness with which an institutional sense of purpose can be made personal to individuals. I suggest to you, however, that the growth in size of nearly all our colleges is a relatively small aspect of this problem. I say "relatively small" both because I think there are other difficulties that are more basic and because I believe that difficulties due to size are importantly relative to the steadfastness and intensity of an institution's sense of purpose.

A strong, explicitly and pervasively articulated purpose is in fact one of the most useful antidotes man has developed for dealing with problems of bigness in any enterprise. Purpose is an especially effective offset to the kind of trouble that bigness brings with it in education. If we can keep the individual student suffused with the right purposes I am not too much worried whether he counts his fellows by the hundreds or by the thousands.

What does perplex and worry me is whether our colleges are themselves sufficiently infused with an overarching sense of purpose that can hold its own, so to speak, with the imperatives toward an ever-higher competence that today fortunately infuse the specialized disciplines of scholarship. I trust I need not disclaim any desire to impair these drives toward intellectual excellence or to limit the power that such excellence generates. I have long believed that a man who has not learned to think precisely about particular things has not learned to think. And surely most of us stand with those who assert that a man who has not acquired knowledge in some depth about something is likely to lack a respect for standards in all things. But after all this is avowed and not merely conceded, who among us has not been taught by his own life that knowledge is neither self-executing nor self-directing?

Of course, we can always answer that this is true but that these other things are someone else's business and that a capacity for commitment and a sense of moral purpose are not properly, or at least importantly, the concern of today's college. I shall mention only two reasons why I believe that any such renunciation of comprehensive purpose at the college level is bad education.

A democracy cannot remain healthy unless the power that resides in its members is inspirited to action and guided by man's experience with good and evil. These things must be taught in home, school, and church, but ultimately I believe such teaching will take its cue from the higher learning of a free society and cannot avoid coming to terms with that learning.

I cannot believe that the pervasive education of a democratic society will long remain healthy if the highest institutionalized expression of that society's education renounces its corporate responsibility for what men are in favor simply of what they know. We do well to remember that a man is always both more and less than what he knows.

Moreover, would we not agree that the liberating quality of liberal learning itself is deeply rooted in the tension that must always exist between a man's competence and the way he uses or misuses that competence in relation to others as he harvests the enjoyment of life?

If the undergraduate sometimes seems to be a particularly inhospitable place for the promotion of a promising marriage between man's reluctant intellect and his faint conscience, let us remember that the end of all education can never be higher than the better management of imperfection and that in our system of higher learning the undergraduate years are probably the last point at which an institution can throw its institutional weight behind this particularly holy form of matrimony.

And this leads to a final word: let us also remember at every point in our working days that an institutional purpose presumes the existence of an institution. Teachers, students, classrooms, laboratories, libraries, trustees, teams and all else on a campus, only become - and remain - an institution when men freely and truly commit themselves to it. Such commitment is the essence of liberation, not its enemy. If we will begin rebuilding the institutional quality of the college at this point I have little worry that we shall find our way through to an institutional purpose that embraces all the imperatives of liberal learning.

As part of the ceremonies attending the inauguration of u Robert Kenneth Carr '29 as President of Oberlin College, honorary degrees were conferred upon six men. Among those honored were President Dickey, who received the Doctorate of Laws, and Kent H. Smith '15 of Cleveland, who received the Doctorate of Science.

President Carr cited Mr. Dickey as "Dartmouth classmate and friend, worthy member of the Wheelock succession, from whom Oberlin's president takes encouragement and inspiration." He characterized Mr. Smith, acting president of Case Institute of Technology, as "citizen and servant of the 'city with a civic heart' to which its sons give loyalty and affection."

President Dickey was presented for the degree by Donald M. Love, Secretary of Oberlin College, who, said:

"It is a happy coincidence that, nearly sixty years ago, another Dartmouth president participated in an Oberlin presidential inauguration. It is by deliberate design that the present president of Dartmouth is here today to sponsor your induction into office, standing god-father, as it were, in witness to your career as a member of his faculty. Beside both of these circumstances, however, there is abundant reason to honor one who has played so significant a role in deepening the educational experience and broadening the intellectual horizons of American youth. An apostle of 'publicmindedness,' and an authority on international relations, he has served his college and his country in the cultivation of a thoughtful approach to public questions and a practical application to the wisdom so attained to 'the building of a sound economic order, the maintenance of a just peace, and the search for values which will enable our culture to survive.' "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNATIONAL SECURITY: Issues and Prospects

December 1960 By LOUIS MORTON, -

Feature

FeatureUNDERWATER TREASURE

December 1960 -

Feature

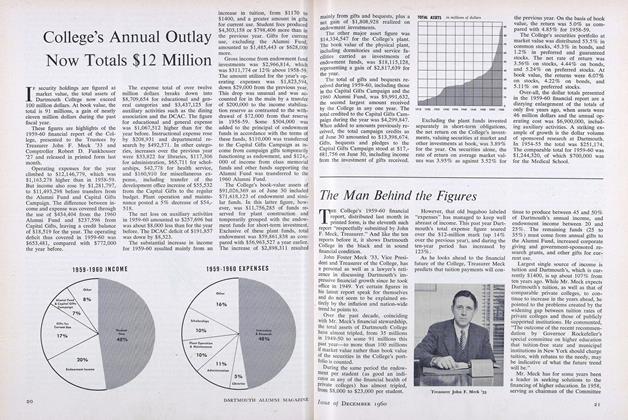

FeatureThe Man Behind the Figures

December 1960 -

Feature

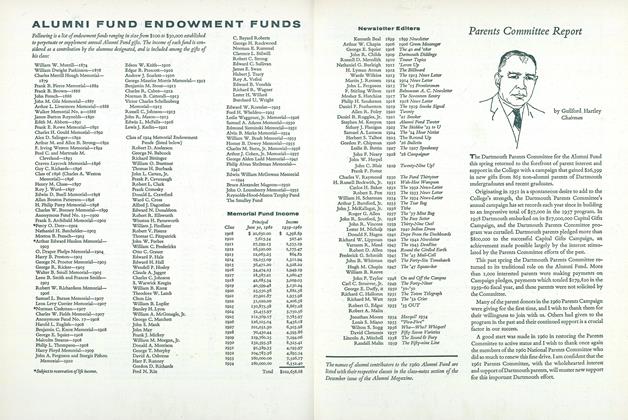

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

December 1960 -

Feature

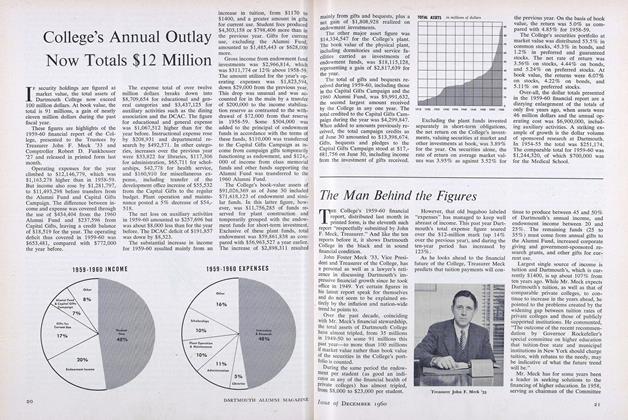

FeatureCollege's Annual Outlay Now Totals $12 Million

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

December 1960 By Donald F. Sawyer '21