Stan Waterman '46, Deep-Sea Diver and Photographer, Helps Find a Sunken Bronze-Age Ship, 3500 Years Old

THE Princeton, N. J., letterhead of Stanton A. Waterman '46 bears a wavy green line, three fishes, and the words "Films Under the Sea." His underwater profession, involving documentaries, television films, and lecture programs, is probably unique among all those pursued by Dartmouth men.

Just recently Waterman completed 3000 Years Under the Sea, a 16-mm. color film, which he will be showing from coast to coast during the winter months. The film is a pictorial record of the underwater archaeological expedition led by Drayton Cochran off the coast of Turkey in the summer of 1959. The expedition bore Flag 178 of the Explorers Club, to which Waterman, a member, made a detailed report that provides the basis for the following brief account of how the exploring party located a Bronze Age shipwreck, the oldest ever found.

In June 1959 the members of the expedition assembled on the Greek island of Spetsai, where Cochran's 71-foot Little Vigilant was prepared for diving operations. As a tune-up for the main exploration, the Cochran group made nine dives on the wreck of the Hydra, a Greek destroyer sunk off the island of Aegina by German dive bombers in 1941. At 230 feet the divers experienced rather acute nitrogen narcosis - "rapture of the depths" - but by the third dive, with careful decompression procedure and timing, they had adjusted to working at that depth. The superb clarity of the water enabled Waterman to shoot movies with only natural light.

From Aegina the party's course took them around Cape Artemesium to Izmir, Turkey, where they picked up some Turkish co-workers, including Haki Gultakin, director of the Izmir Archaeological Museum; and then to Bodrum, home port for the Turkish sponge-diving fleet and survivor of the once-powerful city of Halicarnassus. On the Yassi Ada Reef in the Chuke Channel, commanding the approaches to Bodrum, Waterman and others in the party did their first serious archaeological diving. Sponge-divers had earlier found amphorae in several locations near the reef, pinpointed the summer before by the American archaeologist Peter Throckmorton.

"What we found," reported Waterman to the Explorers Club, "was a veritable graveyard of ships. Starting at the very top of the reef, we discovered cannon balls from an 18th Century Ottoman warship. Twenty feet down along the eastern slope of the reef we found an acre of potsherds, the remains of what must have been an extremely large cargo of amphorae. These amphorae had been gradually smashed by the motion of the sea until not one remained whole. Deeper along the slope, in sixty feet of water, we located another wreck of an amphoraladen ship. This time the water was deep enough to have preserved the jars. Hundreds of magnificent Rhodian amphorae from the first century A.D. were still stacked on the bottom as they must have been on the deck of the ship. These Rhodian amphorae are possibly the most graceful of all amphorae, having lovely tapered bottoms and large handles. . . .

"The amphorae, having filled with sand and sediment, were extremely heavy, even under water. We quickly realized that a rapid and simple technique for raising them had to be applied. We worked in teams of two. One man could lift the amphorae off the bottom and hold it aloft, neck down, while the second diver probed into the neck with a long probe to loosen the deposit inside. When some of the inside had been cleared, the second person would hold his mouthpiece up to the open neck of the amphorae and above his head so that the air would freely vent into the amphorae. Very shortly the jar would become buoyant and start to rise like a giant balloon. At first the ascent would be slow. Then, as the air in the jar expanded, the speed would increase until at the surface the jars literally shot out of the water. A diver at the surface would retrieve the amphorae and swim it over to a waiting boat. In this manner we raised several dozen from the Yassi Ada Reef and at the end of a week had an impressive collection of amphorae with at least six different sizes and shapes from wrecks of ships that spanned almost 500 years. This collection is now. housed in a special chamber in the fortress at Bodrum and is the nucleus of a marine archaeological museum started by Haki Gultakin."

From the Yassi Ada Reef the expedition, following the leads provided by the sponge-divers, moved south along the coast, then southeast toward Finike, stopping along the way to explore wreck sites and ancient, forgotten harbors. One of the leads that excited the party was the report of bronze spear heads found to the eastward, near a remote point of land called Gelidonya Burnu. Despite the slight chance of finding it, an ancient ship carrying bronze cargo would be a great archaeological prize, and the romance of the search more than any real hopes led the expedition to explore the deep where the sponge-divers had found the spear heads.

"All attempts at organized search, sweeping the area with teams of divers, failed," Waterman reported. "It was impossible for teams to stay together and also impossible to retain any sense of direction on such a bottom. We soon found that we had to 'free-lance,' covering general areas as well as possible with two-man teams.

"We searched for two days, from early morning to late afternoon, remaining underwater as long as our safety schedule would permit. On the third day, when spirits had failed and the group was actually beginning preparations for the return trip westward, the discovery of the wreck was made under circumstances that have an adventure fiction ring about them. John Cochran, Drayton Cochran's son, and Susy Phipps, the only girl on the expedition, went down for one last dive. Having despaired of locating the wreck, they were interested in filming some of the giant grouper that abounded in this area. It was at this eleventh hour that John Cochran's sharp eye picked out the obscure, almost indefinable outline of a symmetrical object. He noticed other objects too regular in shape to be part of the bottom. The first object seen was an ancient copper ingot. It marked the location of a ship's cargo that sank to the bottom almost 3500 years ago, although we could not know that at the time.

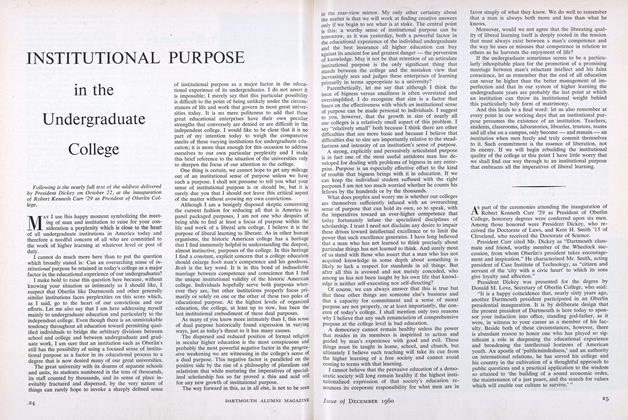

"The discovery started three days of intense work. We found that the ship had gone down in 90 feet of water and had come to rest on a rock ledge at the base of a submarine cliff. Six ingots on top of the ledge were so fused with the ledge and thoroughly a part of the surrounding bottom that they were almost invisible. With the crude prying and hammering tools that we had, we loosened these ingots and raised them to the surface. They varied in exact size, but in general were about 25 inches long, 9 inches wide at the center broadening out to 13 inches at the ends, and 2 inches thick. They weighed close to fifty pounds, and were probably as heavy as 60 pounds originally. We filed into one of the ingots and found that inside it was as pink and shiny as the new copper tubing that we compared it with.

"Under the ingots and around the erratic contours of the ledge we found many sand pockets in which were imbedded smaller artifacts. We retrieved double-bitted axe heads, dagger blades, mining tools, and other smaller pieces, all of bronze. Some pottery was found - only a few shards - and, fascinatingly, parts of rope with the twist still evident. No parts of the hull were discovered, for we had no means for working the sand."

As diving conditions became extremely difficult and hazardous on the third day, and the food supply was running out, the expedition called off its operations and headed back to Spetsai via Rhodes and Bodrum, where the Turkish group disembarked with their archaeological treasure. A few artifacts were brought back to this country for study and identification. Dr. Erik Sjoqvist, a classical archaeologist at Waterman's home base of Princeton, recognized the artifacts as belonging to the late Bronze Age, or about 1500 BC, when the rich copper mines of Cyprus were already supplying the Mediterranean world of 3500 years ago.

The Cochran party's discovery led a University of Pennsylvania Museum expedition to work on the wreck for three months in the summer of 1960. "They went at it with complete equipment, air lifts and air jets," Waterman has written to the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, "and they uncovered an extraordinary amount of material. Quantities of pure tin oxide indicated that the ship was carrying cargo for foundries that would make bronze. They also found parts of the wooden hull, pieces of rope still intact, and Egyptian seals that indicate the wreck is closer to 1300 BC than 1500 BC."

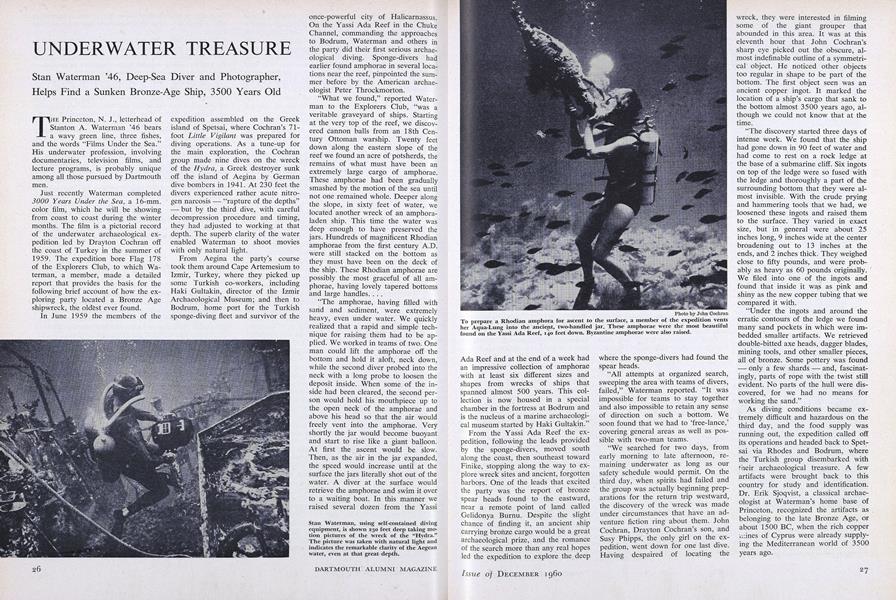

Stan Waterman, using self-contained diving equipment, is shown 230 feet deep taking motion pictures of the wreck of the "Hydra." The picture was taken with natural light and indicates the remarkable clarity of the Aegean water, even at that great depth.

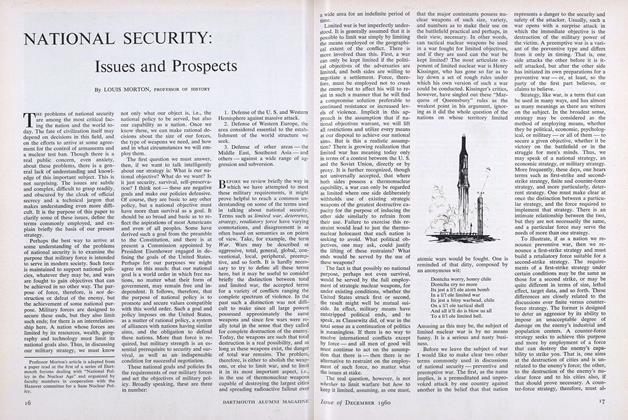

To prepare a Rhodian amphora for ascent to the surface, a member of the expedition vents her Aqua-Lung into the ancient, two-handled jar. These amphorae were the most beautiful found on the Yassi Ada Reef, 140 feet down. Byzantine amphorae were also raised.

Egyptian drawing in the tomb of Rekhmire, Chief Tribute Collector for Thutmose III, showing one of the Keftiu carrying a "cowhide" ingot; and below, one of these ingots shortly after it was raised from the Bronze Age wreck. The ingot weighed 50 pounds and the copper inside was still bright and clean.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNATIONAL SECURITY: Issues and Prospects

December 1960 By LOUIS MORTON, -

Feature

FeatureINSTITUTIONAL PURPOSE in the Undergraduate College

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Behind the Figures

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

December 1960 -

Feature

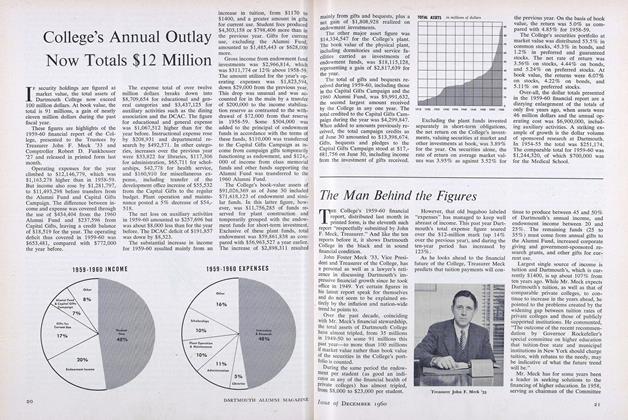

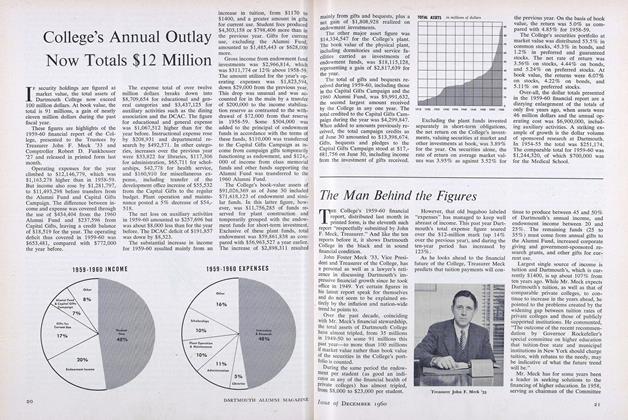

FeatureCollege's Annual Outlay Now Totals $12 Million

December 1960 -

Feature

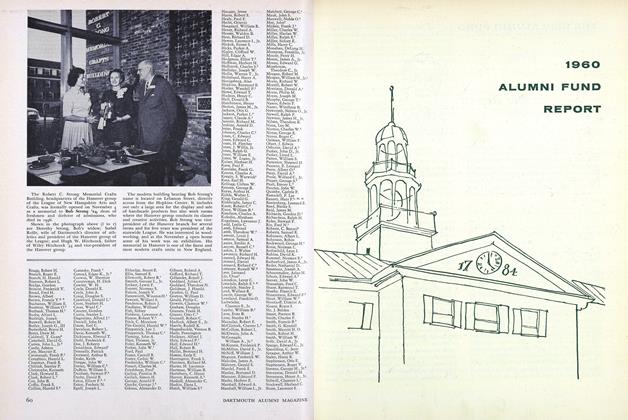

FeatureChairman's Report

December 1960 By Donald F. Sawyer '21

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMOUNT MOOSILAUKE TRAIL SIGN

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureModern Family

September | October 2013 By ALEC SCOTT ’89 -

Feature

FeatureRising Sophomore

June • 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureCan Education Kill the Movies?

JANUARY 1968 By Maurice Rapf '35 -

Feature

FeatureBACK TO THE BOOKS

FEBRUARY 1964 By R.J.B. -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Beat of Terror

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By STUART A. REID ’08