PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

THE problems of national security are among the most critical facing the nation and the world today. The fate of civilization itself may depend on decisions in this field, and on the efforts to arrive at some agreement for the control of armaments and a nuclear test ban. Though there is a real public concern, even anxiety, about these problems, there is a general lack of understanding and knowledge of this important subject. This is not surprising. The issues are subtle and complex, difficult to grasp readily, and obscured by the cloak of official secrecy and a technical jargon that makes understanding even more difficult. It is the purpose of this paper to clarify some of these issues, define the terms commonly employed, and explain briefly the basis of our present strategy.

Perhaps the best way to arrive at some understanding of the problems of national security is to examine the purpose that military force is intended to serve in modern society. Such force is maintained to support national policies, whatever they may be, and wars are fought to gain objectives that can be achieved in no other way. The purpose of force, therefore, is not destruction or defeat of the enemy, but the achievement of some national purpose. Military forces are designed to secure these ends, but they also limit such ends; for there is an interrelationship here. A nation whose forces are limited by its resources, wealth, geography and technology must limit its national goals also. Thus, in discussing our military strategy, we must know not only what our object is, i.e., the national policy to be served, but also our capability as a nation. Once we know these, we can make rational decisions about the size of our forces, the type of weapons we need, and how and in what circumstances we will employ them.

The first question we must answer, then, if we want to talk intelligently about our strategy is: What is our national objective? What do we want? Is it just security, survival, self-preservation? I think not - these are negative goals and make our policies defensive. Of course, they are basic to any other policy, but a national objective must have more than survival as a goal. It should be so broad and basic as to reflect the aspirations of most Americans and even of all peoples. Some have derived such a goal from the preamble to the Constitution, and there is at present a Commission appointed by President Eisenhower engaged in defining the goals of the United States. Perhaps for our purposes we might agree on this much: that our national goal is a world order in which free nations, no matter what their form of government, may remain free and independent. It follows, therefore, that the purpose of national policy is to promote and secure values compatible with this world order. Such a goal and policy imposes on the United States, as a matter of rational policy, a system of alliances with nations having similar aims, and the obligation to defend these nations. More than force is required, but military strength is an essential prerequisite to security and survival, as well as an indispensable condition for successful negotiation.

These national goals and policies fix the requirements of our military forces and set the objectives of military policy. Broadly speaking, these are three in number:

1. Defense of the U. S. and Western Hemisphere against massive attack.

2. Defense of Western Europe, the area considered essential to the establishment of the world structure we seek.

3. Defense of other areas - the Middle East, Southeast Asia - and others - against a wide range of aggression and subversion.

BEFORE we review briefly the way in which we have attempted to meet these military requirements, it might prove helpful to reach a common understanding on some of the terms used in talking about national security. Terms such as limited war, deterrents,strategy, retaliatory force have varying connotations, and disagreement is as often based on semantics as on points of view. Take, for example, the term War. Wars may be described as aggressive, total, general, global, conventional, local, peripheral, preemptive, and so forth. It is hardly necessary to try to define all these terms here, but it may be useful to consider briefly the distinction between total and limited war, the accepted terms for a variety of conflicts ranging the complete spectrum of violence. In the past such a distinction was not difficult to make since all large powers possessed approximately the same weapons and since few wars were really total in the sense that they called for complete destruction of the enemy. Today, the weapons are such that total destruction is a real possibility, and as long as these weapons exist, the danger of total war remains. The problem, therefore, is either to abolish the weapons, or else to limit war, and to limit it in its most important aspect, i.e., in the use of thermonuclear weapons capable of destroying the largest cities and spreading radioactive fallout over a wide area for an indefinite period of time.

Limited war is but imperfectly understood. It is generally assumed that it is possible to limit war simply by limiting the means employed or the geographical extent of the conflict. There is more involved than this. First, a war can only be kept limited if the political objectives of the adversaries are limited, and both sides are willing to negotiate a settlement. Force, therefore, must be employed not to crush the enemy but to affect his will to resist in such a manner that he will find a compromise solution preferable to continued resistance or increased levels of violence. Implicit in this approach is the assumption that if national objectives warrant, we will lift all restrictions and utilize every means at our disposal to achieve our national aims. But is this a realistic assumption? There is growing realization that limited war has meaning today only in terms of a contest between the U. S. and the Soviet Union, directly or by proxy. It is further recognized, though not universally accepted, that where both sides possess a thermonuclear capability, a war can only be regarded as limited where one side deliberately withholds use of existing strategic weapons of the greatest destructive capacity for the purpose of inducing the other side similarly to refrain from their use. Failure to exercise this restraint would lead to just the thermonuclear holocaust that each nation is seeking to avoid. What political objectives, one may ask, could justify the lifting of these restraints? What ends would be served by the use of these weapons?

The fact is that possibly no national purpose, perhaps not even survival, would be served by the full employment of strategic nuclear weapons, for under existing conditions, whether the United States struck first or second, the result might well be mutual suicide. In effect, military means have outstripped political ends, and to speak, as Clausewitz did, of war in the total sense as a continuation of politics is meaningless. If there is no way to resolve international conflicts except by force - and all men of good will must continue to act on the assumption that there is - then there is no alternative to restraint on the employment of such force, no matter what the issues at stake.

The real question, however, is not whether to limit warfare but how to keep it limited, assuming, as one must, that the major contestants possess nuclear weapons of such size, variety, and numbers as to make their use on the battlefield practical and perhaps, in their view, necessary. In other words, can tactical nuclear weapons be used in a war fought for limited objectives, and if they are used can the war be kept limited? The most articulate exponent of limited nuclear war is Henry Kissinger, who has gone so far as to lay down a set of rough rules under which his own version of such a war could be conducted. Kissinger's critics, however, have singled out these "Marquess of Queensbury" rules as the weakest point in his argument, ignoring as it did the whole question of the nations on whose territory limited

atomic wars would be fought. One is reminded of that ditty, composed by an anonymous wit:

Dontcha worry, honey chile Dontcha cry no more Its jest a li'l ole atom bomb In a li'l ole limited war Its jest a bitsy warhead, chile On a li'l ole tactical shell And all it'll do is blow us all To a li'l ole limited hell.

Amusing as this may be, the subject of limited nuclear war is by no means funny. It is a serious and nasty business.

Before we leave the subject of war I would like to make clear two other terms commonly used in discussions of national security - preventive and preemptive war. The first, as the name implies, is a premeditated and unprovoked attack by one country against another in the belief that that nation represents a danger to the security and safety of the attacker. Usually, such a war opens with a surprise attack in which the immediate objective is the destruction of the military power of the victim. A preemptive war is a variant of the preventive type and differs from it only in timing. That is, one side attacks the other before it is itself attacked, but after the other side has initiated its own preparations for a preventive war - or, at least, so the party of the first part believes, or claims to believe.

Strategy, like war, is a term that can be used in many ways, and has almost as many meanings as there are writers on the subject. In the broadest sense, strategy may be considered as the method of employing means, whether they be political, economic, psychological, or military - or all of them - to secure a given objective, whether it be victory on the battlefield or in the struggle for men's minds. Thus, we may speak of a national strategy, an economic strategy, or military strategy. More frequently, these days, one hears terms such as first-strike and secondstrike strategy, finite and counter-force strategy, and more particularly, deterrent strategy. One must make clear at once the distinction between a particular strategy, and the force required to implement that strategy. There is an intimate relationship between the two, but they are not necessarily the same, and a particular force may serve the needs of more than one strategy.

To illustrate, if as a nation we renounce preventive war, then we renounce a first-strike strategy and must build a retaliatory force suitable for a second-strike strategy. The requirements of a first-strike strategy under certain conditions may be the same as those for a second strike, or may be quite different in terms of size, lethal effect, target data, and so forth. These differences are closely related to the discussions over finite versus counterforce strategy. The former is designed to deter an aggressor by its ability to impose an unacceptable degree of damage on the enemy's industrial and population centers. A counter-force strategy seeks to achieve this purpose and more by employment of a force that can destroy the enemy's capability to strike you. That is, one aims at the destruction of cities and is unrelated to the enemy's force; the other, to the destruction of the enemy's nuclear force and to his cities also, if that should prove necessary. A counter-force strategy, therefore, must always be superior to the enemy's. It is also most closely suited to a first-strike strategy, and is capable of serving as a deterrent to a variety of threats. A finite strategy is much less costly, but it is also less flexible since it can be employed for only one purpose — to deter a major strike against the U. S. For other threats, such as one against Western Europe or the Middle East, limited war forces are required.

Deterrence itself is a term that is loosely used and often misunderstood. It may be defined simply as the threat of the use of force to deter someone else from doing something, and in this sense is nothing new in international relations. But it has acquired a special meaning today with the development of nuclear weapons, for the threat is of such a nature as to leave no room for bluffing or for error. The object of a deterrent strategy is to avoid the use of the deterrent weapons, and this creates all kinds of problems.

In the modern sense, a deterrent may be said to consist of three elements:

1. Force, the ability and demonstrable power to inflict an unacceptable degree of damage upon the enemy's homeland.

2. Will, the threat of the use of this force and the unmistakable determination to carry out the threat.

3. Skill, the political ability to make full use of the threat.

The first, I think, is clear. It consists at present of the nuclear weapons and delivery systems of the U. S. and the Soviet Union. The third element, the political skill to employ the threat of this force, is frequently overlooked, but it is an essential element of a deterrent strategy. It calls for the highest skills of diplomacy in not allowing the enemy to get himself into a position where he has to make a choice between thermonuclear war and an unacceptable political defeat. And the enemy has to understand that he must not put you into the same position either. In a sense, this is the art of brinkmanship. "If you cannot master it," said John Foster Dulles, "you inevitably get into war. If you try to run away from it, if you are scared to go to the brink, you are lost."

The second element of a deterrent strategy, the national will and determination to use military force if all else fails, is perhaps the least understood and most difficult to grasp. It has to do with credibility. If we do not believe we will use our military force under any circumstances, how can we expect the potential enemy to believe it? And if he does not believe it, how can this force act as a deterrent? Our task, therefore, is to make the threat of its use credible, and in the final analysis, the deterrent effect of our nuclear force is dependent upon the credibility of its use rather than the degree of destructiveness, assuming both sides have thermonuclear weapons. In other words, a deterrent is not only physical; it is also psychological, and a deterrent strategy involves for both sides a complicated process of "mutual mind reading" based upon a highly subjective and speculative calculus about enemy intentions, the value of objectives, and the estimated costs of a particular action. The disastrous consequences of miscalculation in any one of these or other areas can be enormous. To place our hopes for peace on such a delicate and unstable equilibrium based on the fear of mutual annihilation may not be a pleasant prospect, but the alternatives may be even less pleasant.

Deterrents may be of different kinds and apply to different situations. The three most commonly referred to are: active, passive, and negative. An active deterrent refers to the deterrence of military aggression upon our allies and requires high credibility of the threat and a force capable of initiating a first strike, that is a counter-force. A passive deterrent refers to deterrence against a direct massive attack on one's own nation. Here the credibility of the threat of retaliation is much more certain; only the ability of our forces to survive the initial attack may be in doubt. A negative deterrent aims to prevent a direct attack on oneself arising from the fear of the aggressor that he will himself be attacked if he does not attack first. The problem here is to persuade the other side you do not intend to attack him first, while at the same time you may be developing the capability for doing so. Like passive deterrents, it has a high degree of credibility, and requires, as a minimum, an invulnerable retaliatory second-strike force.

ALL this merely suggests the complexities of a strategy based oil deterrents; it is not possible to do more than that here. Instead, I will try to outline the stages in the evolution of this strategy since 1945. For purposes of convenience, I have divided these 15 years into four fairly distinct, though overlapping phases. The first would extend from 1945 to 1949; the second from 1949 to 1953; the third from 1953 to 1957; and the fourth from 1957 to the present and beyond, projecting to perhaps 1963 or 1964.

The first period, from 1945 to 1949 we can characterize as the period of atomic monopoly by the U. S. During the first two years there was a rapid demobilization of the military machine built up in World War II, followed by a period of rising tension when the U. S. sought to meet the threat of Soviet expansion by a policy of containment and a military force based largely on World War II concepts - i.e., universal military training, emphasis on air and naval power, industrial potential, stockpiling, and the revival of World War II alliance system. The Berlin Blockade in 1948 led to the formation of NATO and the deployment for the first time of U. S. nuclear power abroad. It is in this collective security system and the emphasis on air power and the A bomb that we can detect the emergence of a deterrent strategy.

The second phase of our postwar strategy can be said to begin with the Soviet atomic explosion in August 1949, which altered entirely the security position of the U. S. and its overseas allies. The result was to place first priority on the development of a strategic air striking force (SAC) for the purpose of deterring the U.S.S.R. from attacking the U. S. itself, whereas previously the deterrent had been designed to protect our allies in Western Europe. It was this requirement — to deter attack on the U. S. — that dominated military policy during the period after 1949. But the Korean War complicated matters by setting up its own requirements for conventional ground forces so that from 1949 to 1953, the U. S. sought to attain a balanced force that would be able to push back the North Koreans, deter the Soviets in Western Europe, and meet a variety of threats ranging from all-out war to brush-fire wars. The result, as we know, was perhaps less than satisfactory.

The third phase in the evolution of postwar strategy begins with the first Eisenhower administration in January 1953. By now, our strategic air command was impressive, the hydrogen bomb had been added to our arsenal, and there seemed every prospect that we would remain superior to the Russians. The Republicans, therefore, quickly liquidated the unpopular Korean War, and announced in January 1954 that our policy hereafter would depend upon a capacity "to retaliate instantly, by means and at places of our own choosing." With this policy announcement came what was called "The New Look," that is, the military program designed to support massive retaliation. The central feature of the New Look was the concept of more security at less cost, or in Madison Avenue jargon "more bang for a buck." Ensuing budgets therefore greatly increased the Air Force share of the budget while cutting other forces. Clearly the new strategy was designed as much for economy as for its strategic merits.

Massive retaliation as a strategy was not new. What was new was the emphasis on air power and the effort to utilize this air power for two purposes: to deter attack on the U. S. and to deter attack on our Western European allies on the assumption, to paraphrase Sir John Slessor, that the dog we keep to chase the cat will also chase the kittens. Unfortunately, it didn't work out that way.

The strategy of massive retaliation was obsolete almost from the outset, for the Russians quickly demonstrated they soon would have the capacity to do to us what we were threatening to do to them. Since our strategy was based on superiority of nuclear weapons, it became necessary to expand enormously our strategic air command. In effect, we decided to adopt a counter-force strategy to deter the Soviets from striking us first. At the same time, our deterrent became less convincing for anything but a direct threat against the U. S., thus weakening the NATO defense system.

The Soviet announcement of a successful ICBM launching in August 1957, followed some months later by the launching of an earth satellite, inaugurated the fourth phase of our deterrent strategy. The Soviet achievement, in addition to its effect on American prestige and self-confidence, led to a complete reappraisal of this country's defense posture. U. S. strategy had heretofore been based on manned bombers and the assumption that adequate warning of a Soviet attack would be received to enable SAC to take timely action. Now it was no longer possible to count on such warning, since the flight time of an ICBM is about 20 minutes. The possibility of a surprise attack, therefore, was considerably increased, especially since our national policy ruled out preventive or preemptive war. These facts, combined

with the prospects for future technological breakthroughs in weapons, placed great premium on forces in being, and intelligence activities intensified existing problems and raised many new problems. In effect, the Eisenhower administration adopted a finite strategy in 1957, because it was less costly, but failed to develop the limited war forces required to meet other types of threats. Thus, against a threat to Berlin the administration could only counter with a threat to destroy Soviet cities. Since such action was bound to lead to retaliation against U. S. cities, the threat was hardly credible.

Though our military forces are still superior to those of the Soviet Union, their deterrent value has decreased and the prospects for the immediate future are not reassuring. According to informed estimates, Soviet production of ICBM's is expected to increase over the next few years at a much more rapid rate than U. S. production, so that by 1963 Russia will have 1,500 ICBM's as compared to about 150 for the U. S. This is the so-called missile or deterrent gap, and there seems to be little we can do about it, since production requires a lead time of at least three years or more. At the same time, limited war forces have declined to their lowest point since Korea. The hope that tactical nuclear weapons would overcome the Soviet advantage in conventional weapons has proved illusory, for the Russians now have a similar tactical nuclear capability. The next few years, therefore, promise to be extremely difficult ones. As the advantage shifts to the Soviet side, the danger of a surprise attack increases, and the necessity for protecting our retaliatory force becomes more pressing. In these circumstances, many experts suggest that the U. S. ought to reconsider its commitment to a finite strategy and a second-strike force. There is even talk about the advantages of a preventive or preemptive war in such a situation. Further, some have proposed that the U. S. assist our European allies to develop their own nuclear forces, but the addition of more countries to the nuclear club may raise more problems than it would solve. The limitation of armaments, many hope, will provide a way out of the present dilemma, but not much progress has been made thus far. Or a breakthrough in weapons technology, such as an anti-missile missile, may reverse the present trend and restore the balance. But in any case, there seems to be no immediate way open to alter the strategic equation over the next few years. One can only hope that the consequences of a nuclear attack, even if the chance of success seems good, will deter a potential aggressor, and that both the U. S. and the Soviet Union will continue to exercise the same restraint in deeds if not in words that have characterized their behavior during the last decade.

Professor Morton's article is adapted from a paper read at the first of a series of Dartmouth forums dealing with "National Policy in the Nuclear Age" and organized by faculty members in cooperation with the Hanover committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureINSTITUTIONAL PURPOSE in the Undergraduate College

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERWATER TREASURE

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Behind the Figures

December 1960 -

Feature

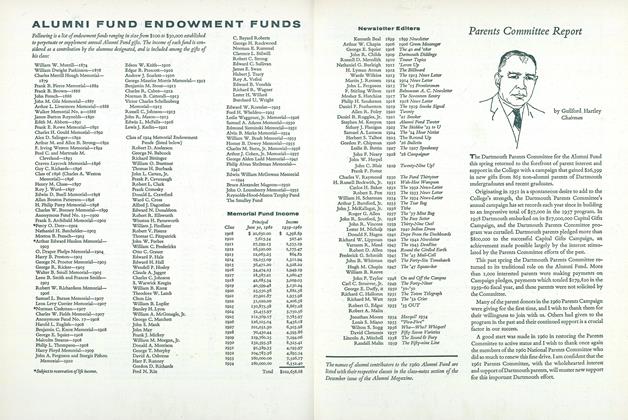

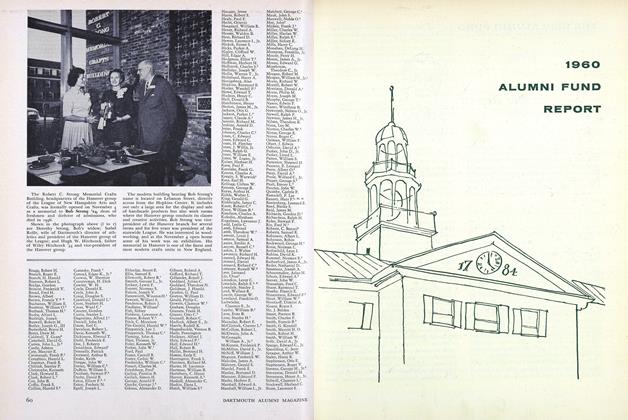

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

December 1960 -

Feature

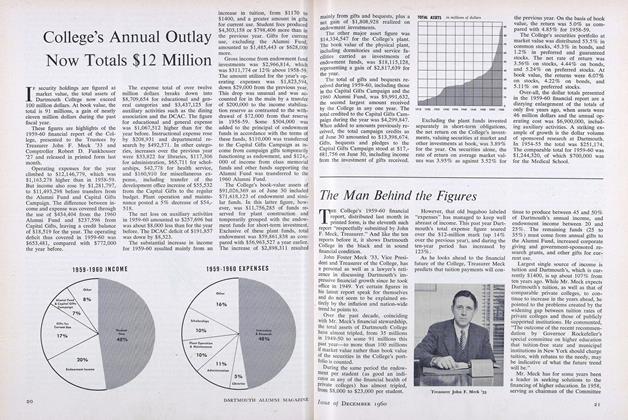

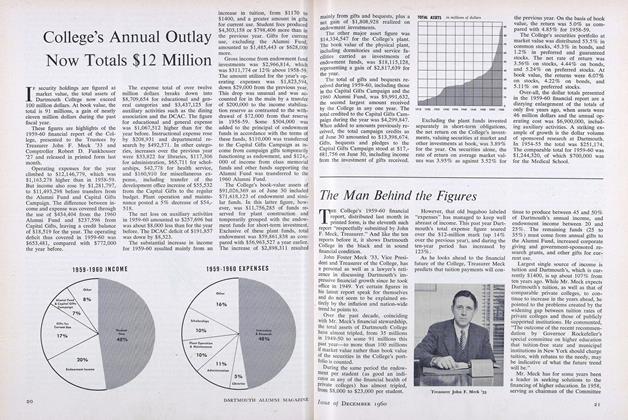

FeatureCollege's Annual Outlay Now Totals $12 Million

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

December 1960 By Donald F. Sawyer '21

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Has Record Attendance

March 1958 -

Feature

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

MARCH 1964 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1968

JULY 1968 -

Cover Story

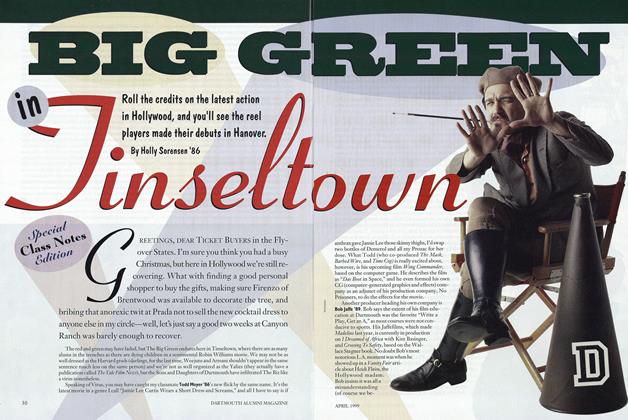

Cover StoryBig Green in Tinseltown

APRIL 1999 By Holly Sorensen '86 -

Feature

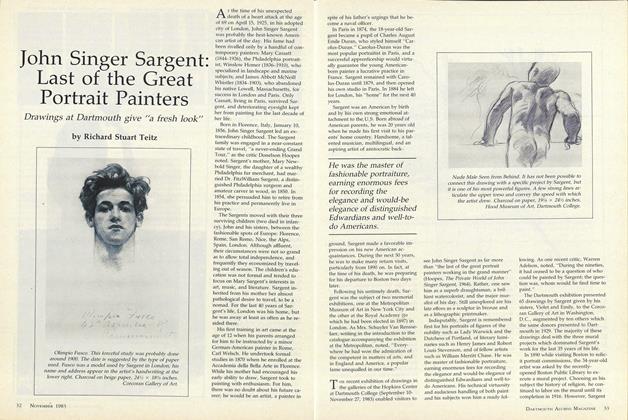

FeatureJohn Singer Sargent: Last of the Great Portrait Painters

November 1983 By Richard Stuart Teitz -

Feature

FeatureThe Comprehensive Classroom:

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Roger D. Masters and William C. Scott