Francois Denoeu, Professor of French at Dartmouth, feels that despite more than 180 years of political independence, Americans are still under Britain's thumb linguistically.

So now, after thirty years of effort, Professor Denoeu has completed a work that he hopes might become the Boston Tea Party of a War of Philological Independence.

He has ready for publication a bilingual French-American (not French-English, please) dictionary. In manuscript form it consists of 16,000 typed pages and makes a pile five feet high.

"The trouble," Professor Denoeu says, "is that American students must understand all three languages — French, English and American — in order to make use of the twenty-odd bilingual dictionaries now in general use."

The dictionaries, he explains, were compiled for the most part by English lexicographers and published in England for use by the British. In the few cases in which Frenchmen wrote them, the authors invariably learned English at Oxford or elsewhere in Great Britain.

For example, he said, take an American student who is. seeking the French word for "gasoline." If he doesn't know that to the British gasoline is "petrol," he can't find the French word, essence. Or he might not know that "fellow" is "bloke" to the British and type to the French. Or he's looking for the French equivalent of "mailbox" (la boite aux lettres) and doesn't know the British word, "letterbox."

These are all common words, widely accepted. When idioms and colloquialisms are introduced, the results are not only often misleading, they are at times downright ludicrous.

Say an American student runs across sefaire attraper while reading French. He turns to his bilingual dictionary and finds: "Get a wigging, be slated, be slanged." Chances are he is still in the dark, but he would understand "to get a dressing down" or "to be bawled out," the American expressions.

Or take danser devant le buffet, in the British idiom "to dine with Duke Humphrey." The meaning is entirely lost on most Americans who would say "to miss a meal."

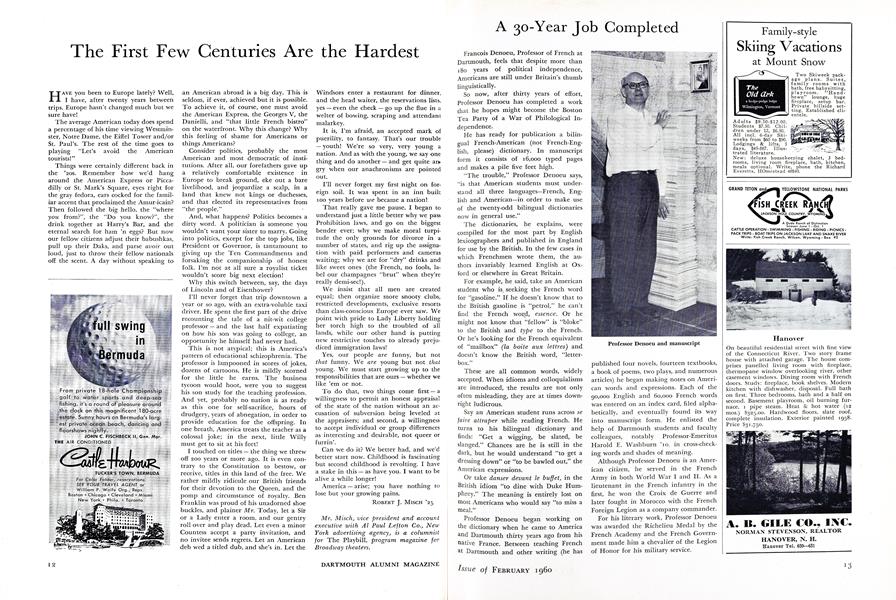

Professor Denoeu began working on the dictionary when he came to America and Dartmouth thirty years ago from his native France. Between teaching French at Dartmouth and other writing (he has published four novels, fourteen textbooks, a book of poems, two plays, and numerous articles) he began making notes on American words and expressions. Each of the 90,000 English and 60,000 French words was entered on an index card, filed alphabetically, and eventually found its way into manuscript form. He enlisted the help of Dartmouth students and faculty colleagues, notably Professor-Emeritus Harold E. Washburn '10 in cross-checking words and shades of meaning.

Although Professor Denoeu is an American citizen, he served in the French Army in both World War I and II. As a lieutenant in the French infantry in the first, he won the Croix de Guerre and later fought in Morocco with the French Foreign Legion as a company commander.

For his literary work, Professor Denoeu was awarded the Richelieu Medal by the French Academy and the French Government made him a chevalier of the Legion of Honor for his military service.

Professor Denoeu and manuscript

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

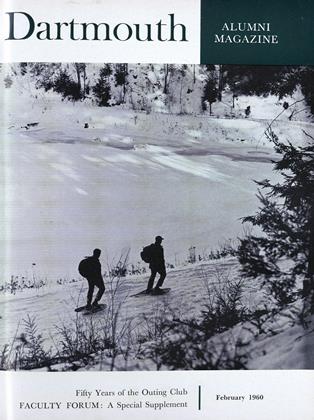

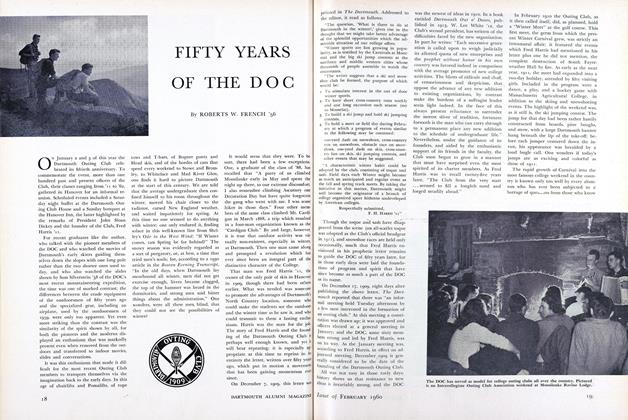

FeatureFIFTY YEARS OF THE DOC

February 1960 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Feature

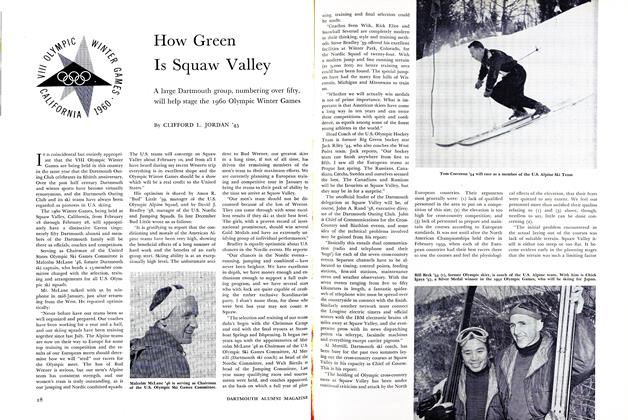

FeatureHow Green Is Squaw Valley

February 1960 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureHow Public Is Music?

February 1960 By JAMES A. SYKES -

Feature

FeatureThe Broadcasters and the Government

February 1960 By ELMER E. SMEAD -

Feature

FeatureIndividuality in Forest Trees

February 1960 By F. HERBERT BORMANN -

Feature

FeatureA Pioneer in Electronics

February 1960 By J.B.F.